A Voyage to Arcturus by David Lindsay. 1920. Ballantine Books, Nov. 1968. [My version: 1st printing, Nov. 1968]

This essay is part of Ballantine Adult Fantasy: A Reading Series.

Table of Contents

David Lindsay and the Road to Ballantine

Reading A Voyage to Arcturus

Parting Thoughts

David Lindsay’s 1920 science fantasy novel A Voyage to Arcturus is a ponderous, clunky, and decidedly unpleasant thing. I have dreaded its approach more than any other of the BAF preface novels because I’ve mostly heard of it in tones of dismay and disappointment, as a literary text, or in the neutral tone that relates an interesting historical fact, e.g. for having inspired C.S. Lewis’s Space Trilogy (1938–1945) or for being a favorite novel of literary critic and self-professed enemy of the “school of resentment” Harold Bloom or for being a work of Nietzschean, gnostic, Platonic, Christian, Manichean, or transcendentalist theory-fiction, depending on the interpreter. Compared to E.R. Eddison’s A Fish Dinner in Memison, which I really struggled to say something useful about, A Voyage to Arcturus is both worse and better. Worse, because it’s just a plain shit novel and at least Eddison was a talented prose stylist who understood language. Better, because Linday’s philosophical ramblings are less objectionable than Eddison’s.

As a novel, as a work of literary art, A Voyage to Arcturus is something like Tommy Wiseau’s disasterpiece The Room (2003) and its own relationship to film as an art form. Which is to say, it’s really quite bad. Indeed, A Voyage to Arcturus has a distinctly Wiseauian flavor, especially in the dialogue, which has a sometimes random, non-sequitur rhythm, while the main character’s actions are often completely unpredictable. It’s almost as if we are reading the novelization of a lost Wiseau film if he had time-traveled to Weimar Germany and set his sight on some Fritz Langian dreamtrip of cerebral science fantasy.

What results from this trippy mashup is bumbling and awkward and incoherent and messy, a disaster so disastrous that it circled well beyond “so bad it’s good,” such that I often felt completely stumped (when I wasn’t bored or annoyed) as a reader and critic. But I will try to work with and make sense of this novel, since it is clearly a text that carries some weight in the history of fantasy and sf alike. Thankfully, there is a small coterie of scholars, critics, and writers—Lewis and Bloom, of course, but also Colin Wilson, Michael Moorcock, Douglas A. Anderson, and Philip Pullman, to give the most prominent names—who greatly value Lindsay and especially A Voyage to Arcturus, with a handful even claiming it to be one of, if not the, most important novel of the twentieth century. I’ve turned to some of their work to help me see A Voyage to Arcturus in the best light possible (even if I have to squint and scratch my head when they call it impressive, remarkable, or genius).

David Lindsay and the Road to Ballantine

David Lindsay (1876–1945) was a Scotsman by birth but spent most of his life in England. He was slightly older than Eddison, Tolkien, and Lewis, but too young to be in the same cohort as William Morris, and he was influenced by the much older George MacDonald, a Scottish writer whose religious fantasies influenced all of these other writers and would also appear in the BAF series (alongside everyone but Lewis). Lindsay was an insurance clerk by training, a clerk in the British army during WWI, and thereafter became a fulltime (and largely unsuccessful) writer; in the 1930s–1940s he operated a boarding house in Brighton with his wife, which was damaged during WWII, and he died ultimately from an abscessed tooth. Lindsay’s biography and the full scope of his small oeuvre are covered thoroughly in The Strange Genius of David Lindsay (John Baker, 1970), a now obscure and rather expensive book co-written by J.B. Pick, Colin Wilson, and E.H. Visak (it can be found online, too, if you know where to look).

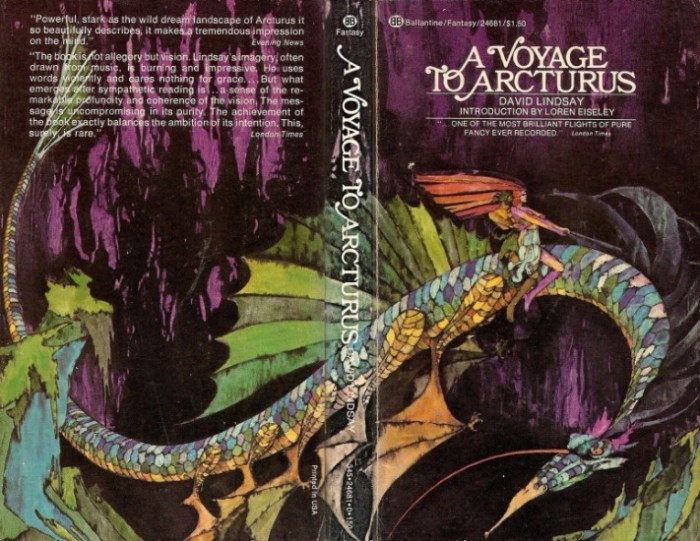

A Voyage to Arcturus was Lindsay’s first novel of several and is by far his best known. Published in 1920 by Methuen, it sold poorly. It was reprinted again in 1946 by Victor Gollancz and sold poorly. Gollancz reprinted it again in 1963 and sold the US hardcover rights to Macmillan the same year. Macmillan significantly edited the novel, according to Douglas A. Anderson, “introducing many hundreds of changes throughout the novel. Some are merely punctuational, but many are stylistic, altering words, phrases and word order.” Macmillan’s edition became the basis for Ballantine’s November 1968 mass market paperback edition, which was covered with a (hideous) wrap-around painting by Bob Pepper, who also did the (equally ugly) covers for Ballantine’s editions of Peake’s Gormenghast series published the previous month in October 1968. I’m curious to know how different the British and American editions are thanks to Macmillan’s changes; I found multiple typos, all punctuation, in the Ballantine edition, but I have to wonder, if Anderson is correct (and he’s a very careful bibliographer!), if Lindsay somehow comes across as a better stylist in the original—it seems unlikely, but who knows!

Ballantine labelled A Voyage to Arcturus as “A Ballantine Science Fiction Classic” on the left-hand corner of the first printing’s front cover, a label given to a number of other mass market reprints of earlier (and more recent) sf texts published by Ballantine in the late-1960s and early-1970s. Notably, after the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series launched just a year later, new printings of A Voyage to Arcturus featured the unicorn head emblem of the series on the cover and cut the sf label. But the initial 1968 printing framed the book as sf. This was both a result of the novel being easily read as a kind of proto-sf that had much in common with, say, Edgar Rice Burroughs’s earlier Barsoom novels or Lewis’s later Space Trilogy, and because by 1968 sf was a very clearly defined market genre and fantasy was still so new as a market category that it made sense to most publishers to put fantasy novels under the sf category.

It’s instructive, then, that the final page of the 1968 printing of A Voyage to Arcturus is an advertisement for Ballantine’s growing sf paperback library, featuring an eclectic range of books by Larry Niven, Ray Bradbury, John Norman, Robert Silverberg, John Wyndham, Anne McCaffrey, Piers Anthony, and, yes, the recent titles by Eddison and Peake. This association of writers and texts—ranging across space opera, sword and planet, dystopian classics, fantasy epics, and Gothic modernism—and the movement of A Voyage of Arcturus between the sf label and a fantasy label in the span of just a few years demonstrates the fluidity of fantasy as a genre category in this early period. Simply put, fantasy was unpindownable as a market category, even in 1968, even after Ballantine had published Tolkien, Eddison, and Peake. Three authors, after all, don’t make a genre, even if their work begins to suggest some contours, parameters, and shared features. Ballantine’s efforts, which would culminate ultimately in the BAF series when Lin Carter was brought on board as a consulting editor in the coming months to steer the direction of Ballantine’s fantasy acquisitions, constituted a crucial genrefication project that we—reading through this series book by book, considering each book both in its own contemporaneous moment of production but also in the contexts of its republication by Ballantine in the swirling mists of the emerging fantasy market c. 1968–1974—get to see unfold in real time through this reread series.

A Voyage to Arcturus is an interesting challenge, then, for thinking about fantasy and how publishers, readers, and critics were beginning to think about the genre qua genre, since the novel has been read with equal aplomb and enthusiasm into the histories of both fantasy and sf. In many ways, A Voyage to Arcturus is perfect proto-sf: it features a journey by rocketship afforded by some sciencey idea (“back rays”) to another planet. But, as Farah Mendlesohn shows in her deft reading of the novel’s rhetorical strategies for introducing, sustaining, and (de)familiarizing the fantastic to readers, the novel is also similar in many ways to portal-quest fantasies (Rhetorics of Fantasy, 24–27). Published in 1920, and seen from the vantage of 1968 and certainly with further hindsight from the perspective of 2025, A Voyage to Arcturus very obviously straddles the line between what would become sf and fantasy.

But like all of of the pre-genre fantasy works Ballantine helped to canonize as part of the history of fantasy, A Voyage to Arcturus existed in its own contexts and drew from disparate traditions both preceding and contemporary to it: not just MacDonald and Burroughs, noted above, but also Arthur Conan Doyle, William Hope Hodgson, and the weird, strange, and supernatural stories popular in Britain from the 1890s to the interwar period (see, for example, much of what is collected in the British Library’s important Tales of the Weird series), not to mention philosophical influences from Nietzsche’s Also Sprach Zarathustra or from Plato’s Republic. A Voyage to Arcturus was not, therefore, without its contexts. Indeed, in both of its previous reprintings it appeared in series that sought to create a semi-coherent idea of “strange fiction” (1946) and “imaginative fiction” (1963) by placing Lindsay alongside M.P. Shiel, Charles Williams, E.H. Visiak, Richard Middleton, and even Sheridan Le Fanu.

Lin Carter, too, seemed to think A Voyage to Arcturus made sense as a fantasy text, since he covered it—quite positively, despite his dislike for Lindsay’s overreliance on allegory—in Imaginary Worlds: The Art of Fantasy (1973), his history of fantasy fiction published as the 58th BAF title. He places Linday’s novel in conversation with MacDonald, Hodgson, and Eddison. And it seems to me that Eddison’s Zimiamvia trilogy and Lindsay’s A Voyage to Arcturus have much in common as works of (science) fantasy that engage worldbuilding and narrative with philosophy and which, in doing so, are particularly concerned with the nature of reality and our purpose, as people, in a(n) (a)moral universe. I also have a hunch that Carter’s familiarity with A Voyage to Arcturus and its value as an intertext with other novels (to be) published in the series is probably what led to it being included in the list of BAF preface titles that he drew up, and as such is probably why the novel was reprinted as part of the series. After all, Ballantine could have continued to publish it as “A Ballantine Science Fiction Classic” to complement their growing sf list.

Reading A Voyage to Arcturus

A Voyage to Arcturus begins, in a fashion already dated by 1920 but calling back to a late-Victorian and Edwardian obsession with spiritism, with a seance. The seance physically manifests a man—Crystalman—from another world before the stunned audience. But the magnificent event is interrupted when a stranger, Krag, bursts into the room, throttles Crystalman to death (whereupon he mistily de-manifests), and invites two of the attendees—Maskull and Nightspore—to join him at an astronomical observatory on a Scottish island, from which they will begin a fantastic journey to the world of Crystalman himself and to follow/find a figure named Surtur. The Edwardian scene of the upper-middle-class drawing room that opens the novel is traded, in the second chapter, for the Gothic atmosphere of the lonely Scottish coast and an eerily abandoned observatory tower. Some science fictional ideas about “back rays” (light that travels backward toward its source) are introduced and the three men about whom we know nothing, except that Maskull seeks some adventure away from the dreariness of modernity and that Nightspore seems to have some knowledge of what’s to occur on their trip, board a back ray-powered rocketship to the planet Tormance, which orbits the star Arcturus (in this novel it is really two stars named Branchspell and Alppain).

Maskull wakes up on Tormance, in a scarlet desert, alone. He is greeted by a woman of this world, Joiwind, who shares her pure Tormancian blood with him, for Earth blood makes it impossible to survive on Tormance. Thereafter, he travels to Joiwind’s home and meets her husband, Panawe. Crucially, Joiwind and Panawe have several sensory organs—a tentacle called a magn, for example, which Joiwind explains “By means of [which] what we love already we love more, and what we don’t love at all we begin to love,” and which Maskull calls “A godlike organ!” (55)—that Maskull doesn’t have but which they teach Maskull to grow, so that he can share in their community and, through the organs’ new/enhanced senses, their worldview. From Joiwind and Panawe, Maskull learns to respect and love all life equally; he becomes a vegan and drinks only the life-giving “gnawl water.” Joinwind and Panawe also have interesting views on gender, suggesting that gender is a kind of murder, that the choice to be masculine or feminine, to present as man or woman in society, “kills” the natural, dual nature of gender that exists in all of us when first born. Joiwind and Panawe read like the kindest caricatures of hippies, decades before the free love movement came into being, and they seek “to love all” as the greatest good that can be done (57). This is reflected in their understanding of God or the creator, whom they call Shaping (and who also goes by Surtur), and who made humanity in his image, so that, as Maskull interprets it, “the brotherhood of man is not a fable invented by idealists, but a solid fact” (65). Eventually, Maskull leaves these two to continue his search for Surtur.

This segment of the novel establishes the pattern of Maskull’s physical and spiritual journey across Tormance. In each segment, Maskull will progress from one place to another, from south to north across the planet, traversing huge distances. He will come to a new land, meet a new person, and discover their philosophical outlook and a new answer to the question of who Surtur or Shaping or Crystalman is/are (with the suggestion often being that they are one in the same, that they are something like “God,” creator of the universe, or perhaps just the god of this portion of a tripartite universe, and so on with as many variations as there are characters). In most cases, the people of each new land have a different sensory organ that Maskull grows, abandoning whatever sensory organ he grew in a previous land. He comes, then, to believe wholeheartedly in the new creed of whatever land he is in, a change of mind and heart often afforded very explicitly by his new sensory apparatus and therefore by his new sensorial relationship to the world. Some event will then prompt Maskull to leave; occasionally the event is a crime he commits, often a murder, or he follows a wanderer who seeks new knowledge in the next land.

It takes a while for this narrative structure to become self-evident, so that it is a bit of a shock when Maskull travels further north after leaving the wonderfully peaceful and all-loving Joiwind and Panawe, and encounters Oceaxe. The sensory organ of Oceaxe’s people is called a sorb and, on replacing Maskull’s breve and poign, and transforming his magn into something less loving, this new organ allows Maskull to assert his will over others, assuming his will overpowers theirs. Thus begins a brutally cruel section of the novel wherein Maskull murders Oceaxe’s husband simply because he can, causes Oceaxe herself to be murdered by another woman, Tydomin, and forcibly “absorbs” another man—Digrung, Joiwind’s brother—into his own self out of fear and shame that Digrung will tell Joiwind of Maskull’s murders and his new slavish devotion to his own willing self.

Maskull isn’t much of a character—for he has no stable personhood in this novel; he is fickle, ever-changing, and driven by seemingly random flights of fancy, underscored by the basso continuo of cruelty and rudeness that characterizes many of his (inter)actions after his encounter with Oceaxe—so much as a cipher for different ideas and beliefs explored and experimented in each new land he visits. Put another way, Maskull’s journey across Tormance is a loose narrativization of a set of philosophical dialogues, with Maskull as an insert for Lindsay and his interlocutors as inserts for various philosophical traditions or positions. At the center of these dialogues is always the question of the nature of God, which is really another way of saying the nature of humanity’s relationship to the universe and which implies a whole set of subsidiary questions: Why are we here? What is truth? What is reality? Is life pain or pleasure? And so on. You know, the big cliche questions of philosophy.

Canny readers will see in A Voyage to Arcturus glimpses of Buddhist, Theosophist, (Neo)Platonist, existentialist, Manichean, and other philosophical traditions. A non-dialectical duality is absolutely central to Lindsay’s exploration of ideas. And often the “wise” figures Maskull interacts with are described in ways that resemble eastern, and especially South Asian and Himalayan, mystics or gurus (who became widely known in the West for the first time during Lindsay’s own life; see Brown’s The Nirvana Express for historical context). In addition to the larger questions about life and meaning and purpose, Maskull’s dialogues also range across topics such as gender (a major concern for Lindsay, who even includes a third-gender with the neopronouns ae/aer), music, art, love, and sex. Little is said in this book of ethics (except that murder is a sin, though Maskull never faces any judgment or consequences) or of the social. Ethics and the social are secondary to (what I read as) the self-serving search for Maskull’s self/identity and an answer to the question of our relationship to the universe/reality/truth, which I cannot help but gloss as another way of asking “And how am I important?” When ethical questions do arise, they are always swept away by Maskull’s progress to a new domain, a new philosophical dialogue, a new set of sensory organs and orientation to the world.

The reader invested in existentialist thought, especially Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, or concerned with Neoplatonism, or with questions of truth or reality, or with whether pleasure or pain is the greater force in the universe—and I am decidedly not interested in these things except for their value to intellectual history; frankly, these move me hardly at all—will likely be deeply moved by A Voyage to Arcturus. Indeed, as noted above, some consider it to be the most important novel of the twentieth century. Others, however, will likely find it unmotivating if not impenetrable. Not because the ideas are complex (they are not, insofar as Lindsay presents them), but because Lindsay lacks a throughline and rejects all ideas, by the end, except for a final, unsatisfying truth: that God, or rather Crystalman, is in fact a force of malevolence who exists to suck up all the pleasure in the universe, which has its source in Muspel, a world or idea or universe that radiates goodness and pleasure.

Maskull’s final revelations in the admittedly bold conclusion of the novel are twofold. First, that he is the impure soul of Nightspore, and has come to Tormance to die and thereby to cleanse his soul of Self, so that Nightspore can experience the truth of the universe. The second revelation, the truth of the universe, is described as follows:

The truth forced itself on him in all its cold, brutal reality. Muspel was no all-powerful Universe, tolerating from pure indifference the existence side by side with it of another false world [that of Crystalman], which had no right to be. Muspel was fighting for its life—against all that is most shameful and frightful—against sin masquerading as eternal beauty, against baseness masquerading as Nature, against the Devil masquerading as God…

Now he understood everything. The moral combat was no mock one, no Valhalla, where warriors are cut to pieces by day and feast by night; but a grim death struggle in which what is worse than death—namely, spiritual death—inevitably awaited the vanquished of Muspel… By what means could he hold back from this horrible war! (286–287, ellipses in original)

Pain, we learn, is the purifying force that cleanses the soul of Crystalman’s masquerade, while pleasure is the masquerade itself. Only an elect few can withstand the pain of the universe, such as a journey across Tormance with all its torments to the soul, its battering between philosophical positions, and so see through Crystalman’s grin and understand him for what he is: the devouring force that corrupts, ensnares, and tricks.

Of course, coming at the very end of the novel, after having stumbled through a dozen different philosophical positions, and with the grossly off-putting Maskull as our guide, it’s unclear how the final revelation relates to the rest of the ideas in the novel. Moreover, what exactly Muspel is, or Crystalman, or all the multiple dozens of other ideas and images invested with weighty symbolism throughout the text—none of this is ever clear. A Voyage to Arcturus is to me confusing, rambling, maddening, qualities that are no doubt responsible for why its devotees find it so compelling (and which I could get behind if I found the muddle of ideas in any way worth pursuing). And it is compelling to many, otherwise A Voyage to Arcturus would not have become something of a cult classic, let alone one that is clearly resonant at a deeply personal level for those who admire it.

I find it difficult, however, to take anything of real value from the novel’s conclusion and its relationship to Lindsay’s narrative structure. C.S. Lewis offered a reading of that structure in his essay “On Stories”:

In each chapter we think we have found his final position; each time we are utterly mistaken. He builds whole worlds of imagery and passion, any one of which would have served another writer for a whole book, only to pull each of them to pieces and pour scorn on it. (11)

Murray Ewing, in response to Lewis, suggests that we can read each sequence of the novel as rejecting the following ideas (I am quoting his table in full; all credit to him!):

| Sequence | Rejects… |

| Séance | Social life and shallow spirituality |

| Joiwind/Panawe | Lovingkindness for all living creatures/self-sacrifice |

| Oceaxe/Ifdawn Marest | Will-to-Power struggle |

| Spadevil/Sant | Dedication to duty |

| Swaylone’s Isle | Art as a way to truth |

| Threal | Religion as a way to truth |

| Sullenbode | Sex/sexual love |

| Gangnet | Mysticism and self-abnegation |

Ewing points out that not every sequence ends with an outright rejection, and certainly not with the Crystalman grin glimpsed on the faces of the dead (and which mocks Maskull’s search for meaning). Further, Ewing suggests, “I don’t think we can say that the things [Lindsay] rejects are of no value, only that they are not the ultimate value, and this is what Lindsay is searching for.”

I’m more inclined to agree with Lewis, however, because while it’s true that, say, Maskull’s rejection of lovingkindness and turn to will-to-power struggle does not mean that lovingkindness is not valuable or even that Lindsay believed it is not valuable, the rejection of idea after idea in favor of the final truth raises the question of how we should weigh and evaluate the value of any idea that is not what Ewing calls “the ultimate value.” A simple answer, a single value, I think, offers us very little. Sure, the revelation of pleasure as a trick and pain as the truth that burns away Crystalman’s obfuscating fog makes for a bold, shocking ending but one of shallow meaning. Moreover, if A Voyage to Arcturus is the story of Maskull cleansing his soul through pain, we are left, in the end, with no way to understand what a cleansed soul means. We are instead given the suggestion that Maskull/Nightspore must cleanse his soul again and again, must move through the sequence of philosophical inquiries across Tormance again and again, to re-learn the Truth. I don’t know what to do with that, except to assume that the revelation is itself a transformational kind of knowledge—a mic drop I don’t have the ears to hear.

Parting Thoughts

Discussing A Voyage to Arcturus with Lewis and Brian Aldiss, Kingsley Amis related that:

Victor Gollancz [who had republished Lindsay’s novel in 1946 and 1986] told me a very interesting remark of Lindsay’s about Arcturus; [Lindsay] said, “I shall never appeal to a large public at all, but I think that as long as our civilisation lasts one person a year will read me.” I respect that attitude.

I borrow this tidbit from Brenton Dickieson, author of the blog A Pilgrim in Narnia, who tackled A Voyage to Arcturus in homage to that novel’s great advocate Lewis. Like me, Dickieson found the novel highly objectionable on a literary level. It’s a rather hilarious piece that reminds me very much of Joanna Russ’s extreme dislike of the novel, which she critiques at length in her wonderfully curmudgeonly 1969 essay “Dream Literature and Science Fiction,” referring to A Voyage to Arcturus alongside the work of A.E. Van Vogt, Edgar Allan Poe, and several others as a kind of “anti-literature” that gestures obsessively at lofty ideas without doing much with them. While I think Russ is wrong about the depth to which Lindsay engages philosophical ideas in A Voyage to Arcturus, and, in fact, I read her dismissal as a hyperbolic reflection of her lack of interest in Lindsay’s ideas, I share her and Dickieson’s sentiment that A Voyage to Arcturus is a dull affair.

As a work of theory-fiction, though, A Voyage to Arcturus is perhaps unparalleled. It uses the trappings of proto-sf and proto-fantasy, of the strange and the weird, of adventure stories, to narrativize a deeply serious search for meaning. The questions asked mean little to me, the answer given even less. But my response is personal; A Voyage to Arcturus’s influence is cultural and historical. The 1920s were a period of reckoning, rethinking, consolidation, and experimentation. A period reflecting on the devastations and social transformations caused by WWI (indeed, Adam Roberts reads the novel as, at least in part, an allegory for the war, in Fantasy: A Short History, 65–66), dealing with the ascension of modernism and attendant cultural formations, as well as the demise of the old order of European empire and governance that transformed the continent and led to experiments like the Soviet Union and the Weimar Republic.

Unsurprisingly, a number of BAF titles date from the “long” 1920s of the interwar period. As evidenced by the very existence of the novel and by its place alongside, for example E.R. Eddison in the very same decade, who also used similar narrative forms to ask similar questions (but with radically different answers), A Voyage to Arcturus was clearly a necessary novel that responded forcefully to its times. I don’t have all the tools to make great sense of Linday’s theory-fiction, and I don’t enjoy or agree with much of this book—though it has moments, such as Lindsay’s wildly imaginative landscape of Tormance—, but I recognize A Voyage to Arcturus’s value as a yawp in the darkness of an existentially terrifying universe.

For that reason, for responding to darkness with a stark—if, to me, unsatisfying and deeply unexciting—creed, A Voyage to Arcturus fit well into the late 1960s milieu of the BAF preface titles. The 1960s were much like the 1920s, a period of reckoning, rethinking, consolidation, and experimentation. Many of the ideas explored and rejected, or at least passed over, in Maskull’s spiritual adventure across Tormance—spirituality, mysticism, lovingkindness, will-to-power, and experiments in art, sex, and faith (not to mention drugs) as paths to Truth—would be at home in the dynamic of counterculture and backlash that formed the central tension of cultural life in the US during the 1960s–1970s. Indeed, if A Voyage to Arcturus is a sincere search for meaning through philosophy and faith, and is a killing of God that tears through the veil of Crystalman’s world and reveals the masquerade of his world of pleasures, then it is a novel that speaks directly to what Hugh McLeod diagnosed as the religious crisis of the 1960s. In evidence of its resonance and influence in this period, A Voyage to Arcturus was adapted into a very bad, but very sincere student film in 1970. Alongside works by Tolkien, Eddison, Peake, and Beagle, those authors who paved the way for the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series, Lindsay’s novel was symptomatic of a culture in crisis seeking meaning, even if written for a different time and place. Republished by Ballantine, now Lindsay spoke to new but familiar crises of faith, meaning, and belonging, and, in this new context at Ballantine, did so through an emergent genre framework that brought together fantasy novels old and new alike.

For those interested in A Voyage to Arcturus and compelled by the philosophical questions it raises, I highly recommend Adelheid Kegler’s 1993 article “Encounter Darkness: The Black Platonism of David Lindsay,” which is the most erudite exploration of Linday’s philosophy that I read in anticipation of this essay. Kegler lays out Lindsay’s influences and major concerns, drawing from other writings by the author, and gives an incredible overview of how he engaged with the writing of, especially, German existentialists. Her article helped me understand why A Voyage to Arcturus is the way it is and to admire aspects of it that I initially glossed over or dismissed. I still don’t like or agree with the novel, but I understand it better and am even, begrudgingly, somewhat impressed by it as a work of theory-fiction.

Next in the Ballantine Adult Fantasy reread series is Peter S. Beagle’s first novel, written when he was just 19, A Fine and Private Place. It will be a very different sort of text and a breath of fresh air.

To get notifications about new essays like this one sent directly to your inbox, consider subscribing to Genre Fantasies for free:

Acknowledgements

Warm thanks to Andrew Butler, Farah Mendlesohn, Andy Sawyer, and Steven Shaviro for suggestions of good critical readings on Lindsay’s A Voyage to Arcturus—suggstions without which I would have had a harder time making sense of this obtuse novel.

4 thoughts on “Ballantine Adult Fantasy: Reading “A Voyage to Arcturus” by David Lindsay”