Venba. Visai Games, 2023. PC, Switch, PS, Xbox.

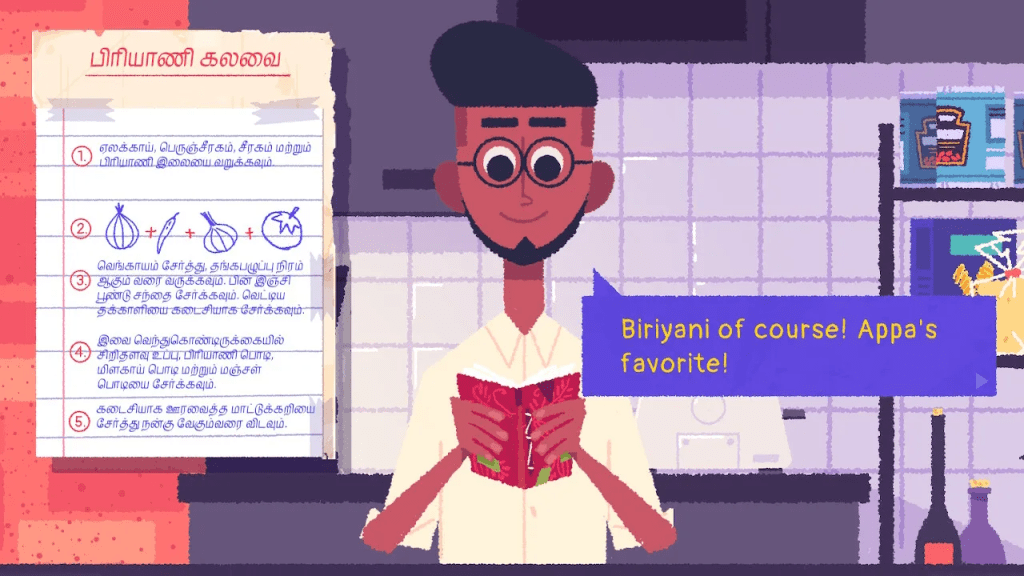

Venba by Visai Games appeared on multiple best of lists for 2023 indie titles. Venba is described as a “narrative cooking game” and billed in its marketing as a “heartfelt story of family, love, loss, and more,” a game where you “explore, converse, experience” “the challenges that arise from day to day life.” While the idea of a cooking game is anathema to the very idea of fun, Venba captured me with its beautiful, vibrant aesthetics and promise of an engaging, emotionally intelligent story of a Tamil immigrant family living in Canada in the 1980s. Some tutorials of gameplay showed a fun dive into the art of South Indian cuisine and reviewers on social media convinced me the game was exceptional.

So I climbed out of my long gaming rut—I didn’t even enjoy The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom (2023)—and found myself charmed by Venba, eager to try out some new recipes myself, and wanting more from this beautiful game with so much promise.

Venba’s cover copy, so to speak, reads:

Venba is a narrative cooking game where you play as an Indian mom who immigrates to Canada with her family in the 1980s. Players will cook various dishes and restore lost recipes, hold branching conversations and explore in this story about family, love, loss and more.

The story begins in 1988, shortly after the titular Venba and her husband Paavalan have immigrated to Canada from Tamil Nadu. Neither speaks English well and they find work incredibly difficult to come by. We learn that they may have moved here because theirs is an inter-caste marriage (at least, it’s mentioned that family in India were so strongly against their marriage that moving to Canada seemed to be their only option, though perhaps I’m reading too much into this after the harrowing experience of Perumal Murugan’s Pyre, set in Tamil Nadu).

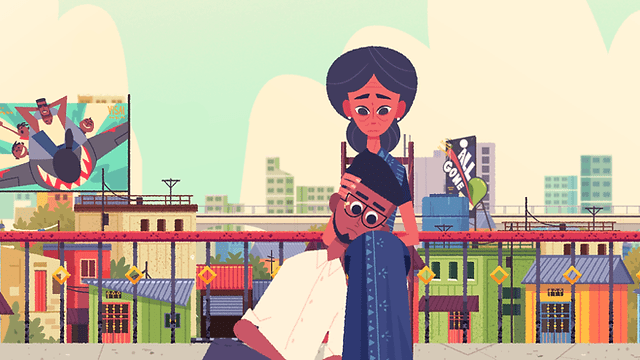

Venba and Paavalan’s life in Canada between 1988 and 2016 is told in short vignettes that jump in time every few years. In that time, Venba and Paavalan have and raise a son, Kavin, and struggle to find meaningful and profitable work. Paavalan is forced into jobs he’s way overqualified for by virtue of his poor English skills and the racism of Canadian bosses, while Venba, a beloved teacher back home, is unable to secure anything more than occasional teacher aide work. Venba and Paavalan seem isolated, with no Canadian desi community mentioned or shown, and Paavalan is even the victim of a hate crime in the 1990s. Meanwhile, their son Kavin undergoes the now well-trod first-generation desi experience: he refuses to speak Tamil, won’t eat his mother’s food at school, prefers pizza to biryani, and can’t wait to get away from home come time for college. The last third of the game shifts narrative perspective away from Venba to Kavin and his growing awareness of the loss he’s experienced by distancing himself from his Tamilness and his parents. He is now a young professional writing for a TV show about high schoolers that wants to celebrate his heritage with a Tamil character but he feels uncomfortable with the way this younger generation doesn’t shy away from its Indianness and embraces its cultural foodways. So he begins to explore cooking Tamil food and the memories of his youth, leading to a reconciliation with his mother who has moved back to India (Paavalan died a few years earlier).

Venba is a truly beautiful game. The art is designed to look hand-drawn and the palette pairs rich, warm colors (especially yellows, blues, pinks) with design elements from South Indian culture. Especially notable is the food art, which is a testament to the design team’s love of South Indian cuisine; one can almost smell the tarka blooming, the saffron scent of the biryani, and the coconuttiness of the puttu. The only awkward element here is character movement, which is thankfully minimal but looks awkwardly like the flash games of the late 2000s.

It’s also a beautiful sounding game. In addition to naturalistic recordings of food cooking (oil sizzling, pressure cookers steaming), Venba incorporates a good deal of Tamil music—excitingly, all music made for the game. In an incredible feat for a small indie game, Venba has an original soundtrack of songs written and recorded for the game, performed by Tamil artists, including one song by major Tamil film composer, Deva. Polygon interviewed game designer Abhi about the soundscape of Venba and how its soundtrack takes players on a loving journey through the history of Tamil film music.

Venba takes less than half an hour to play, depending on how quickly players to figure out the recipes, and the game unfolds primarily through dialogue players read. There are two ludic systems at work in Venba: dialogue trees and click-and-drag cooking puzzles.

Venba is dialogue heavy and occasionally allows the player to make minor dialogue choices, usually between two options that lead to subtly different approaches to character development. For example, choosing dialogue options on behalf of Venba, players are offered two options to define Venba’s growing concern about her relationship with Kavin. She can either confess to her Paavalan that (a) she cannot understand Kavin and the person he’s becoming or (b) that Kavin seems to have no interest in his Tamil heritage, his parents, or their culture or language. Option (a) suggests a slightly more aggressive tone, one that blames the young Kavin for abandoning his Tamilness in favor of the Canadianness and belonging that has eluded his parents; option (b) suggests ambivalence, fear, and sadness about the growing distance between immigrant parents and a Canadian-born child who fears to eat his South Indian dishes at school and can barely speak Tamil.

Such subtlety characterizes most of the dialogue tree options (there are maybe 20 in the whole game) and imbues the narrative with a sense of emotional seriousness, that there are stakes to the slight differences with which we choose to express ourselves. That said, it’s not clear that the branching dialogue has any effect on the story—the outcome is the same in each scene either way. In other words, the carefully considered subtleties of affect written into the dialogue options don’t impact the story in any way beyond the player’s personal experience of it. And perhaps that’s the point—the quiet expression of our worries or the tone we choose to take in a specific moment of frustration with a partner might not always have long-term consequences; these are, after all, only a handful of scenes in nearly three-decades of life and growth.

On the cooking end—the central promise of the game and the greatest beneficiary of its vibrant aesthetic style—the gameplay is again relatively simple. As the narrative jumps through time, the windows we get into this family’s life are centered around moments where Tamil food comes to define the emotional, social, and personal relations at stake. For example, the game starts with a sick Venba deciding to make idlis for Paavalan, who doesn’t know how and can’t be bothered to learn (she chides him for this, he repents). Venba hasn’t made idlis in a long time and, as with most recipes in the game, has to figure it out using her amma’s recipe book. The recipe book is central to the game’s narrative and also part of the puzzle of cooking, since the recipes are often smudged or torn, so the player has to do some guesswork and, in some cases, rely on memories Venba has of her mother cooking (told through black-and-white dialogue-only “flashbacks”; more on this later).

Cooking in Venba involves clicking on an item and dragging it to where it should be, e.g. in a pot, blender, sifter, or bowl. Some mechanics, like turning on a heating element, sifting flour, or mixing dough are accomplished by turning the controller’s joysticks. But in all, the mechanics are very rudimentary. The order of elements in the cooking process are the main puzzle of the gameplay, since the recipe book obscures key steps. If the player messes up, the sequence starts over from the most recent logical place (you’re not overly punished by starting from the very beginning). Most of the cooking “puzzles” are incredibly easy and can be solved either with common cooking sense the first time around or with one or two trials-and-error attempts. Most recipes only take 3-5 minutes to get through and very little information is given about the foods themselves. In the course of the game, players will cook South Indian dishes like idli, puttu, biryani, kozhi rasam, a multi-course meal with whole fried masala fish, and several varieties of dosa (I think this is everything, though I might be missing a dish).

Indian cuisine is generally thought of by non-desi white folks as a difficult, if not unapproachable cooking tradition. Sure, you can get it at restaurants, but who can really cook it? So many ingredients, so many steps, so many cuisine-specific cooking implements, not to mention some flavor profiles that are not familiar to non-desi people. Some of this is partly true—I don’t have an idli or puttu maker, though could buy them at my local South Asian grocer, and since I started cooking South Asian foods I’ve had to buy a wider range of ingredients (things like fenugreek, cardamom, and turmeric aren’t staples in most white Americans’ kitchens)—but these are also true of French and Italian cookery beyond the simplest meals, which require, for example, familiarity with things like how to make different roux or which of 30 types of pasta is most appropriate for a dish. As I’ve spent the past 5 years learning to cook food from across the range of global foodways, I’ve learned that every cuisine has beginner and expert dishes, every cuisine has things anyone can learn to do well. More often than not, a fear of the unknown or blatant racism keep us from seeing other cuisines as approachable and, more importantly, makeable as home-cooked meals rather than occasional restaurant fare.

The great joy of Venba is that it makes even the “toughest” dishes seem approachable. This could be because gameplay, of course, can’t account for all the many things that can go wrong in cooking. In Venba, you don’t have to worry about controlling the heat of the oil or the tightness of the pressure cooker lid or the doneness of your rice or whether you screw up flipping your dosa. But Venba deals in the basics of the process of South Indian recipes and some things that are fundamental across much of South Asian cooking, for example the preparation of a dish’s tarka, the order of adding aromatics, how tomatoes release water and change the way the dish cooks, and the need to pay attention to the mechanical properties of equipment used (when to turn up or down the heat, how to orient idli trays, etc.). Like all cooking, South Asian cooking is a tested process that, sure, you might screw up—Venba, in the early years of the game’s narrative, can’t recall what might seem like staple recipes—but you can also screw up microwave mac-n-cheese, so why not give biryani a try?

This is the beauty of Venba’s semi-pedagogical cooking gameplay, that it demystifies South Asian and specifically Tamil cooking, makes it feel approachable to any player who can get through the puzzles of the well-worn recipe book. What’s more, it doesn’t frame this story of revealed approachability as one told to white people—that is, for the sake of enlightening non-desi audiences; it’s not a project of cultural outreach, in that sense—but rather as the story of Venba seeking comfort in foods from home that she had not properly learned to cook before emigrating and, later, as the story of Kavin reconnecting with the heritage, culture, and tastes he shunned, with the parents he seemingly disavowed.

With this in mind, I want to focus on the final third of the game, the portion focused on Kavin, because here the narrative grows richer and shows the promise of Venba, its design, and its method of storytelling through dialogue, interactive recipes, and flashbacks that give meaning to both the recipes and their entwinement in characters’ life stories. As noted, toward the end of the game, Kavin is a writer for a TV show who becomes uncomfortable with the way the show wants to celebrate Tamil heritage by featuring a Tamil high school student happily eating “Indian” food. The showrunner suggests chicken tikka masala, but Kavin points out that’s not really an Indian dish let alone a South Indian one, so he goes in search of a recipe and lands on kozhi rasam—“Indian chicken soup,” as he describes it to the white showrunner. He decides he has to at least try cooking the soup for the sake of authenticity, so digs into his mother’s (and grandmother’s) recipe book. He has difficulty with the Tamil and the damaged recipe book, and this serves as a puzzle for players to work through as he (and we) make tamarind water, bloom the tarka, brown the chicken, make the soup.

The narrative here is multi-layered, with several flashbacks to when Kavin was a sick child being fed comforting rasam while his mother received news that her own amma had died back in Tamil Nadu. Moreover, the recipe instructions are given to players in jumbled English, representing Kavin’s limited understanding of Tamil. At the end of this emotionally rich scene, Kavin decides to quit the show and visit his mom in India, to grow closer with her—she teaches him to make dosas—to apologize for his absence from her life (especially after Paavalan’s death), thank her for the sacrifices she made, and generally try to make up for lost time with his mother and learn about his Tamil heritage (he notes that he feels “like a tourist” in India).

I love this portion of the game because it plays with Kavin’s language barrier, challenges his emotional distance from Tamil cuisine and, through the food, his own family. The narrative ups the ante on the ludic significance of the cooking gameplay, uses the recipe book as a much more interesting puzzle by showing the book for the first time in Tamil (it appears in English before this, to underscore that the player, as Venba, can read the book just fine) and by giving only partial translations, and makes the player feel as though they are truly in the deep end (the ingredients, for example, are shown now in more supermarket-esque packages and Kavin discards them messily as he pushes haphazardly through the recipe). Here, the story’s narrative, the dialogue’s interaction between Tamil and English, the use of memories, and the experience of cooking all interweave beautifully to tell the story promised by Venba’s promotional material.

The final act of the game, however, shows how narratively thin the early portions of the game are. This is, after all, a game about Venba, but her story is only sparingly told and it’s rarely something the player gets to interact with at the same level as in Kavin’s portion. That is, most of the early game is spent watching dialogue happen, clicking for the next sentence, and occasionally choosing one of two branching dialogue options (with little narrative significance to those options). While two-thirds of this is spent with Venba, this portion never reaches the artistic height of the final section about Kavin. The game thus feels like a love letter to Venba, but told from the perspective of a child, say, someone like Kavin, who only superficially understands his mother’s experience and hasn’t fully thought of her as a person, but as a story (and one that is almost a cliched representation of the immigrant experience, something that could have been significantly enriched and personalized). And it leads to the game, as a whole, feeling artistically unbalanced; personally, I found the first portions of the game charming but emotionally flat, if not boring.

To put this in perspective, let’s take, for example, the flashbacks that intercut Kavin’s attempt to figure out cooking the rasam and his feelings about bringing Indian food to school as a kid. These flashbacks show his mother receiving heartbreaking news, yearning for home but stuck in Canada, and choosing to remain in Canada for a son who grows to resent her because of her Tamilness. Kavin also realizes the significance of the conversation he has as a sick child with his mother, realizes that on that day when she was lovingly caring for him, she had just learned of her mother’s death. The rasam scene is beautiful, artful, and painful because of the interplay between the flashback and the contemporary cooking narrative. There is, as noted, the option to use flashbacks in some of Venba’s cooking puzzles to recall aspects of the cooking process obscured or left out of the recipe book. But these aren’t really flashbacks; rather, when activated, the game overlays black-and-white onto the screen and shows dialogue boxes between Venba and her amma. That’s it. When compared with the emotionally powerful use of flashback in Kavin’s portion of the story, these earlier scenes feel impoverished; they were chances to build a more engaging story that makes Venba into a person with her own experiences and memories.

To be sure, Venba’s story takes center stage in the first portion of the game: she struggles in her desire to become a teacher, but can’t; she struggles to connect with Kavin, but can’t; she loses Paavalan and is left living alone, sending texts to her son that often go unanswered and making a feast for him in the hopes he’ll turn up (he doesn’t). We see the story of a woman who is emotionally scarred by the immigration experience and ultimately left alone. She grows increasingly confident in her cooking abilities (the last time we cook as Venba it’s not a puzzle, the game tells you what to click and voila, you’ve made a multi-course meal!). And she learns that, in order for Kavin to grow and explore his dual identity, she needs to return to India and focus on her own life. So it is Venba’s story, but her story feels shallow in comparison to the final portion spent on Kavin. It left me wanting so much more from the game in the way it handles Venba’s internal life—would that we had seen the flashback scenes with her mother, that we had seen her amma writing in the recipe book, that we had learned why Venba never learned to cook, why her and Paavalan were driven to leave India, and so much more.

Venba is a major accomplishment. It is beautiful, emotional, and at its best it excellently marries limited gameplay features with excellent storytelling. It has moments of exceptional artistry that show the promise of its creators—especially game designer Abhi, co-writer Shahrin Khan, and the art team consisting of Sam Elkana, Rae Minos, and Danik Tomyn—and its studio, Visai Games. While I left wanting more from Venba and for Venba herself, I was impressed by the uniqueness and boldness of this little game. Venba punches above its weight in art, sound, and soundtrack, and tells an endearing story of a Tamil family and foodways.

One thought on “Playing “Venba” (2023)”