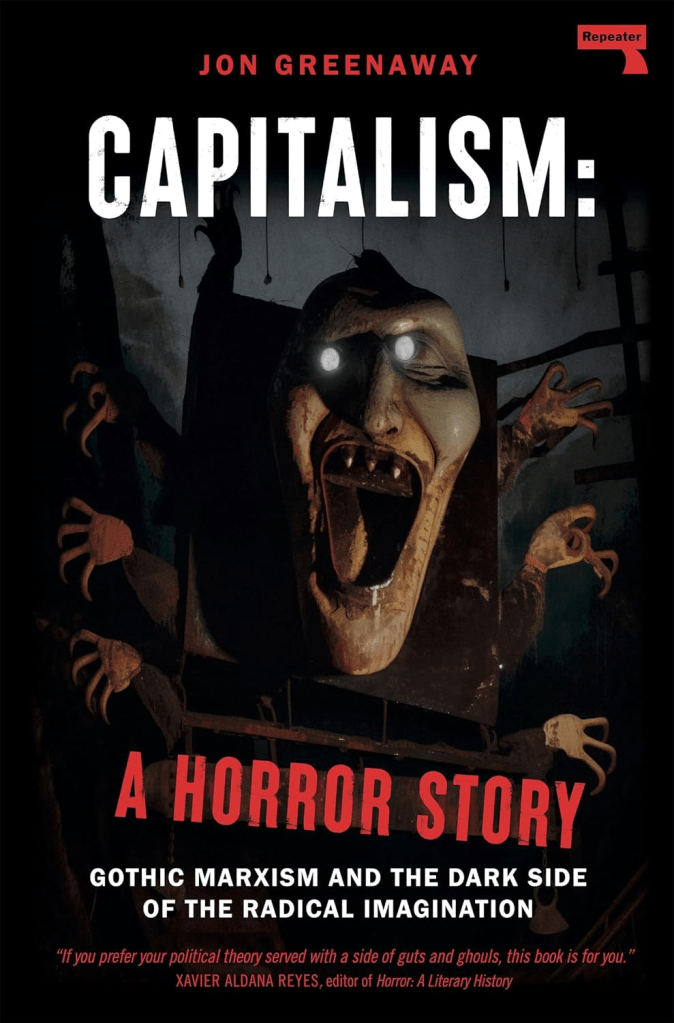

Capitalism: A Horror Story: Gothic Marxism and the Dark Side of the Radical Imagination by Jon Greenaway. Repeater Books, 2024.

What does it mean to see horror in capitalism? What can horror tell us about the state and nature of capitalism?

These are the questions posed in the marketing copy that prompts readers’ entry into Jon Greenaway’s Capitalism: A Horror Story, recently released by the indie Marxist publisher Repeater Books, co-founded, among others, by Mark Fisher and Tariq Goddard. This short book offers a dual study of the Gothic tradition of Marxism—that is, Gothic Marxism—and the radical imagination of horror—that is, the Marxist Gothic.

Despite its brevity at c. 200 pages, Capitalism: A Horror Story is a tour de force of Marxist theory and Marxist readings of horror texts, including classics like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Bram Stoker’s Dracula, and more recent works, mostly films, such The Platform (2019), Parasite (2019), Ready or Not (2019), The Sadness (2021), Possessor (2020), The Beach House (2019), Crimes of the Future (2022), The VVitch (2015), Suspiria (2018), Pulse (2001), Unfriended: Dark Web (2018), Host (2020), the Saw and Purge franchises, and A Dark Song (2016), and the novels Tell Me I’m Worthless (2021) and Manhunt (2022).

Jon Greenaway has published two books in 2024, his first two books, which demonstrate his intellectual and political bonafides as both deeply interested in the utopian strand of Marxist theory and in horror. His first book was an introduction to the utopian philosophy of Ernst Bloch for Zer0 Books and its influence is keenly felt in Capitalism: A Horror Story, which extends the unique utopian theories of Bloch into a work that asks how Gothic Marxism can help us to read horror and how horror can help us to refine Gothic Marxism. The book opens with the obvious connection to the famous line from the Communist Manifesto that a specter (or spook or hobgoblin, depending on the translation of Gespenst) is haunting Europe, introducing the key point that there is a clear sense of horror and the language of the Gothic throughout both Marx’s philosophical works and later Marxist writing about capitalism. Indeed, so prevalent is this language, and timely in the century of Gothic’s emergence and rise to mass cultural status by the end of the Victorian period, that a number of scholars have already written extensively on this tradition they call Gothic Marxism. Greenaway seeks to expand this tradition, to merge it with Blochian utopian theory, and to introduce to it a consideration of the Marxist within the Gothic. As he makes clear in the introduction, there are two strands of thought being brought together: first, the “understanding [that] the form [of the Gothic and horror] [is] a reflection of the cultural anxieties of a given moment” and, second, the tradition in Marxist cultural criticism “that appreciates horror as a phenomenological element of life under capitalism” (13). The goal, then, is to read capitalism as a horror story through a cultural critical approach to horror stories themselves: “not just as disposable entertainment, but as a record of our collective unconsciousness” (13–14).

The book, though short, unfolds across eight chapters. Chapter one provides a theoretical and historiographical overview of “the dark way of being red,” that is, a history of Gothic Marxism as a strand of thought, giving particular primacy to Blochian utopianism as an important way of engaging and understanding the political through mass culture, which offers a “horizon of possibility” for “the bringing into being of utopia” (27). Though I’ve struggled in the past—and again when reading this book—with terms like “horizon of possibility” or “utopian possibility” (and similar variations), and what they actually mean for a politics of social change and revolutionary struggle (despite having used this kind of language naively in my own writing, e.g. my chapter in Uneven Futures), I’ve come to ultimately understand them as meaning that texts help us think through systems of oppression, and that thinking through those systems of oppression and their operations, through texts, helps us to better understand what it might mean to be liberated, to live differently, to live “otherwise” (as Ashon Crawley has theorized). My critique remains that, like Bloch’s daydreams, the utopian possibilities texts offer us seem to be highly individual and depend, in large part, on our ability to read texts critically in ways that open us up as readers to the realities of oppressive systems, and to take from them (or elsewhere in conjunction with them) the tools for self- or collective liberation. I believe I understand the intent of such theoretical framing and rhetoric, even if I question the limits of such critique to engender change, liberation, revolution.

After establishing the Gothic Marxist tradition in which the book will operate, and how it will expand on that tradition through Blochian readings, chapter two then offers the first set of readings of films that map the ways in which capitalism becomes “a social relation mediated through things,” creating relationships between class, bodies, family, and capital itself. Greenaway offers readings of three 2019 films—The Platform, Parasite, and Ready or Not—that expertly show that “capitalism is not just a system but an interpersonal force, a traumatic reshaping of subjectivity that one is forced to endure in the wreckage of history” (41–42). These three readings are really quite good and demonstrate that Greenaway is not only a talented theorist but a capable critic as well. It’s in reading like these, and those that follow throughout the book, where Capitalism: A Horror Story is at its best, where Greenaway is able to cut loose from the (somewhat dogmatic strictures of) Marxist theory and move into a space of textual interpretation of the Marxist Gothic—the “structure of feeling” that is horror—that lays the awfulness of the system bare.

The chapter ends, however, a bit oddly, with the suggestion that all three films offer “the possibility of something other,” “that the cultural moment [of very contemporary global neoliberal capitalism] is not closed, despite the best efforts of capitalist realism’s stranglehold on the imagination” (54). Each of these films in fact ends, yes, with a glimmer of possibility, but those possibilities are far from utopian: a starving child survives The Platform (a sort of reworking of heteropatriarchal investments in children as the future), Grace survives the wealthy family’s sacrificial ritual by herself making a deal to become rich in Ready or Not, and Ki-Woo promises to become rich to free his father from the Parks’ mansion in Parasite. With the arguable exception of The Platform—which I haven’t seen—these are not utopian glimmers, they do not transcend capitalism in any sense, but rather these endings return to it, their characters ending with the conviction to work in service of it. Perhaps they are, as Greenaway notes, like Blochian daydreams (“the ground on which we come to realize what we are missing”), but if so these daydreams are wholly circumscribed by the logical of capitalist realism: these films don’t offer escape in any meaningful sense, but they instead demonstrate the gutting inescapability of the contemporary moment under global neoliberal capitalism. The only hope, for these characters, is hope within the system—and I fail, really, to see the liberatory gesture here, though I in fact appreciate these movies because they fail to offer a simple alternative to a world that has none. While I really value Greenaway’s readings throughout the book, as chapter two demonstrates, they are occasionally twisted awkwardly to demonstrate an always-utopian quality to the narratives, belying any sense that horror could have other functions or do other critical work.

I won’t spend too much time going over the other chapters, and wanted to linger with the first two mostly to demonstrate what this book does well—for me, as the particular reader and thinker I am—and what I found challenging about it. Chapter three offers a study of Frankenstein and Dracula and introduces the concept of monstrosity as a social position (in life) and metaphorical tool (within texts) for opening of spaces of “utopian possibility,” offering “being monstered” as a mode of transgression within/under capitalism. Here, Greenaway draws smartly on the work of Paul Preciado, especially Can the Monster Speak? Chapter four turns to body horror in the era of COVID-19; chapter five to witches as a particular kind of monstrous (feminine) subjectivity (this is, for me, perhaps the most disappointing chapter in terms of texts and readings); and chapter six to haunting and ghost films in the era of platform capitalism, with a focus on films like Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Pulse (2001) and the Zoom screen film Host (2020) that narrate the hauntology of the Internet and our interactions through the web (this is an incredible chapter!). Chapter seven combines necropolitics with neoliberalism to theorize necro-neoliberalism through the long-running Saw and Purge franchises (another place where the readings are themselves very good and insightful, but somehow again twist a utopian possibility out of texts that harshly resist such readings). Chapter eight returns again to the idea of the monstrous and argues its centrality to the “utopian function” of the Marxist Gothic (143). And the conclusion furthers this thread of monstrous utopianism as the central means by which we can face “the various monstrosities of the present” “to rescue and reclaim a future”—a concept that I am wholeheartedly sympathetic to but find challenging to grasp as a political, rather than textual-interpretive, practice.

For me, Capitalism: A Horror Story is not a careful theorization of horror, as a genre. There is a strong sense in the Marxist sphere of cultural studies, especially in scholarship on genres like science fiction and horror, that anything worth being interested in—personally or critically—must be redeemed through a claim that it is somehow utopian. Often, too, this leads to totalizing claims about the genres in question, especially with regard to the politics of genre. Yes, Greenaway is careful to read texts in their historical contexts; that is, in the contexts of the capitalist formations that they attend to or are symptomatic of. But because Greenaway does little work to explain his understanding of the Gothic and/or horror (let alone the distinction between the two), both are reduced to an ahistorical understanding of the genre as always about capitalism and as always utopian (see above about readings that twist the texts toward a utopianism that I find lacking in some cases).

It might be the case that what Greenaway means is that there is a strand within the Gothic and horror that, because of its generic affordances, is particularly open to Marxist and utopian readings. It’s possible that this specificity is implied, but the statements throughout the book are always framed as being about the Gothic, about horror the genre, or about the figure of the monster—generally, not specifically—regardless of context. Here, horror becomes a blunt instrument of Marxist theory, rather than a vibrant, multifaceted, politically complex horizon of texts (sometimes reactionary, sometimes conservative, sometimes radical) that wield the affordances and/or transgress the limitations of the genre in ways that cannot always be reducible to a singular claim about the genre’s politics as a whole. Genres, I want to argue, do not have politics in and of themselves, but their instantiations in texts and in textual traditions (cycles, literary movements, the work of an author, responses to a particular moment), do. I have similar frustrations with totalizing theories about the politics of fantasy and science fiction, and had hoped, given Greenaway’s capacious theorizing of Gothic Marxism, that the approach to horror qua genre would be similarly nuanced.

But, my reservations about genre theory aside (which admittedly might seem parochial to some Marxists and theoryheads), Capitalism: A Horror Story is a careful, clever, and thorough work of Marxist and especially Marxist utopian theory—and I think that’s the best way to understand this book, as contributing primarily to Marxist theory by way of readings of horror. Indeed, that this is primarily a work of Marxist theory—and a rather accomplished one—is demonstrated by the paeans that open the book, blurbs from a range of smart leftist theorists I admire, like A.V. Marraccini, Xavier Aldana Reyes, and Robert T. Tally, Jr.

Theory is not where my critical interests lie, exactly, but for me this book is truly good when it engages primarily with the Marxist Gothic and offers solid, convincing critical readings of horror novels and films. It is also, really, only here where my ability to engage is activated, since I have little to say about Marxist theory, with the principal exception of the concerns raised above. Others who are of the theory persuasion will, I think, be impressed by Greenaway’s depth of familiarity with Marxist criticism and his impressive handling of thinkers from Marx to Agamben to Benjamin to Bloch, and many others who Greenaway draws on in his visionary approach to Gothic Marxism. I would hazard that any future work on Gothic Marxism would overlook this book to its detriment.