Black Book / Чёрная книга. Morteshka, 2021. PC, Switch, PS, Xbox.

I have never played a game like Black Book. There is truly nothing like it.

As a story about rural Russia at the end of the nineteenth century, on the verge of major technological and social revolutions; as a window into a folkworld that is complex, nuanced, and feels very much alive; and as a folk horror fantasy narrative that weaves together Slavic, Permian, and Orthodox Christian folklore and belief systems, Black Book utterly amazed me. It is, moreover, a singularly and heartbreakingly beautiful game—the kind that calls out for an art book, but sadly has none—with a powerfully evocative soundtrack that includes regional folk songs recorded for the game. There is nothing like it.

Black Book—Чёрная книга (Chyornaya kniga) in Russian—was developed by the very small (c. 5 people!) Russian indie game studio Moreshka, established in the mid-2010s and located in the Perm region where Black Book takes place, about 800 miles northeast of Moscow. The studio’s name is a multilingual play on French mort (death), Komi mort (man), and matryoshka (a Russian nesting doll). Their focus as a studio is developing games that, like Black Book and their first game, Mooseman (2017), “are mythology and ethnic-based with the narrative and worlds supported by historical facts and folklore” (see their “About Us” page). This places Morteshka in a wave of indie studios across the world that are developing games driven by local/regional—and especially non-Western and Indigenous—histories, cultures, and folklores. These include recent games like Never Alone / Kisima Inŋitchuŋa (2014; Iñupiaq), Mulaka (2018; Rarámuri), Raji: An Ancient Epic (2020; Hindu), Skábma: Snowfall (2021; Sámi), Upirja (2022; Balkan Slavic), Blacktail (2022; Polish), Tchia (2023; New Caledonian), Tales of Kenzera: Zau (2024; Southern African Bantu), and Two Falls / Nishu Takuatshina (2024; Innu and French Canadian), and the forthcoming games Island of Winds (Icelandic) and Windstorm: The Legend of Khiimori (Mongolian), to name a few. To this I’d also add Venba (2013), a charming game about Tamil foodways I wrote about earlier this year.

Narrating Black Book

The frame story of Black Book is that of a villager from Vilgort, located in the Cherdynsk uyezd (district) of Perm krai (governorate), a region in the western foothills of the Ural mountains that was a historical gateway to Siberia and a mixture of Russian settlers and Indigenous Permian peoples (an ethnolinguistic group speaking one of the Permic languages—Komi, Udmurt, Besmeryan—of the Uralic branch of the Finno-Ugric language family; these people were once called Chud’/Чудь in medieval Old East Slavic chronicles). This villager-narrator is perhaps a contemporary man, someone who “remembers” what has been passed down from times long ago; the tsar, the Bolsheviks, and the Soviets are all rendered in the past tense. His tale—the narrative of the game we play—is recited as a village story, a local legend of triumph and tragedy, meant to explain why there are no longer any sorcerers or demons plaguing the land. The villager’s tale, this game, is an etiology of the transition from “premodern” times of pagan belief that bled through Orthodox Christianity to “modern” times of science, where beliefs of the past have faded to folkloric curiosities. And yet, here in Black Book and true to Morteshka’s mission as a developer, such tales bring to life the forgotten past: the stories, worlds, cosmologies, and lifeways of a Russia long ago but not so long ago that it can’t be remembered. Who knows, maybe it’s real, our villager narrator suggests, but maybe it’s not? Who knows!

The story we play, the story remembered by this unnamed, out-of-time villager, is that of Vasilisa, living in rural Perm in 1879, as she becomes a great koldunya (sorceress/witch/knower) in order to free her dead fiance from the fires of Hell. In order to do so, she must break the seals on the eponymous Black Book, gifted to her by her grandfather Egor, an older koldun (sorcerer/warlock/knower) who raised Vasilisa. By breaking the seven seals, Vasilisa will not only shape herself into a powerful koldunya, but will be rewarded after the seventh seal is broken with a single wish—granted by a mysterious, unnamed demon who encourages Vasilisa’s sorcerous growth throughout the game. Vasilisa intends to use the wish to bring her fiance back to life, for in Christian theology a person who commits suicide is destined for Hell in the afterlife. To break the seals, Vasilisa needs to defeat major spirits and demons—broadly referred to as chorts—who represent the folk-knowledge domains of each seal (aspen, water, spruce, death, etc.).

The game is thus structured around “chapters” that tell parts of the overarching story as Vasilisa aids the villagers of Vilgort and nearby Cherdynsk settlements. Each chapter offers up a “monster of the week” that Vasilisa must seek out and defeat, befriend, or bend to her will, to break a seal. These bosses (in ludic terms) are each different from the last, offering a chance for the game to delve deep into local articulations of East Slavic and Permian folklore and Orthodox Christian beliefs. Each chapter is subdivided further into “days,” with the ebb and flow of time giving both urgency to Vasilisa’s quest—after a certain number of days, per folk belief, her fiance will have passed through the gates of Hell and no longer be saveable—and structure her interactions with villagers (who come and request help, medicine, knowledge, etc. during the day) and chorts (who are only active at night).

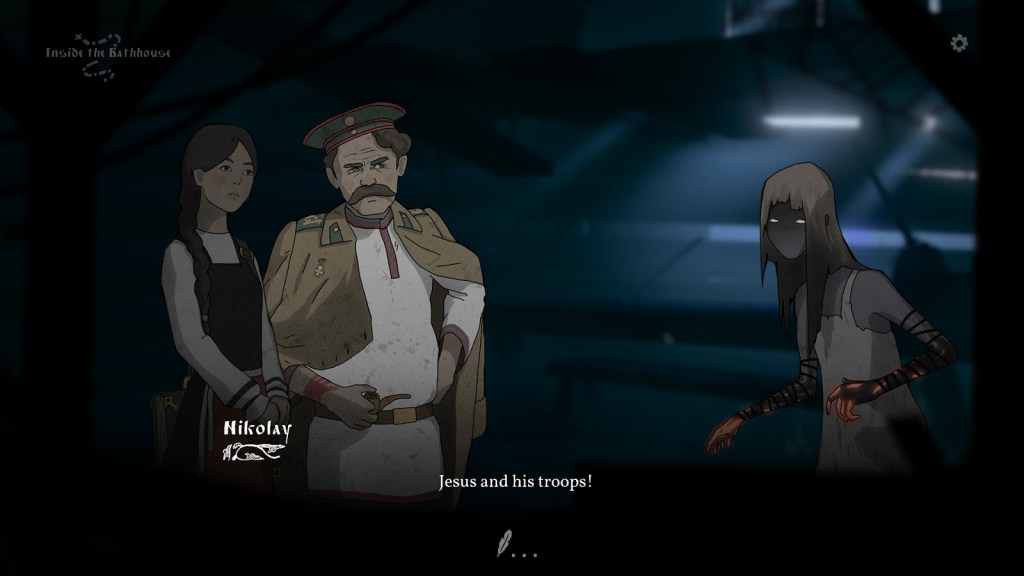

Take, for example, chapter one, which revolves around breaking the first, aspen seal of the Black Book. In Russian folk culture, the aspen was considered a cursed wood, associated with all manner of chorts, but aspen also happens to be a good wood for building saunas—or banyas, bathing houses, which hold an important place in Russian life. This contradiction means that banyas, like many aspects of rural nineteenth-century Russian life, can be dangerous, a home to all manner of spirits and thus in need of a set of specialized rituals to control the relationship between humans and non-humans when and where they meet. The chapter begins with Vasilisa agreeing to help Nikolay, a former military officer who was dared by friends to enter a banya at night, at which point he was attacked by a monsteress who would only let Nikolay free he promised to marry her. Vasilisa is tasked with identifying the monsteress—a bannik, or chort who inhabits a given banya—and figuring out a way to get Nikolay out of the marriage. Things get more complicated when Vasilisa discovers that the bannik is actually a changeling, a human child who was switched with another creature by an obderikha (a female bannik); this changeling requests help escaping the spirit world, which requires a set of ritual objects that Vasilisa must collect. And so on. The chapter is structured around the finding of the ritual objects, which require their own tasks to get, and the navigating of the rituals and knowledge required to free the changeling (including tracking down her birth mother).

This one task—help Nikolay get out of marrying a chort—morphs into a dozen others, all of which rely on building knowledge and village relationships to accomplish, so that the changeling girl can be released from the spirit world and the obderikha defeated, breaking the aspen seal. The events of this chapter have knock on effects in later chapters, which, for example, tell the story of Nikolay marrying the now-human changeling-woman, the wedding being interrupted by a powerful enemy sorcerer, the guests being turned into werewolves, Vasilisa getting lost in a mystical forest in search of them, and so on. And in the midst of all that, Vasilisa does minor, unrelated tasks for villagers, reaps occasional monetary rewards, gathers herbs, plays durak (a card game), recruits allies who can travel with and fight alongside her, and fights the chorts that structure the folk experience of the countryside—whether chorts sent by rival kolduni (pl. of koldun[ya]) or chorts living their lives haunting graveyards, protecting crossroads, inhabiting mills and cellars, possessing children, guarding forests, and so on. Black Book is a pleasingly narratively complex story with an even more complex storyworld. But how does it work, ludically?

Playing Black Book

To put it in the most basic terms, Black Book is a deck-building roleplaying game. Black Book blends elements of visual novel storytelling and 3D exploration to move Vasilisa through the storyworld. Much of the game takes the form of a visual novel, where static figures speak to one another in a set location; these are flat, 2D experiences that contrast to the very occasional moments—typically two or three times per chapter—when you can explore a 3D environment as Vasilisa, usually to look for clues to solve a mystery. The 2D and 3D art styles differ wildly and the 3D figures are significantly less detailed, pared down to basics, though they are charming in their own way. These 3D set pieces are also used for the fights against chorts. To get from place to place, players are given a map of where Vasilisa can go each night in order to complete that night’s objectives; the map spreads out from the starting location—usually Egor’s izba (house)—and traverses the countryside from village to village. Players select the location they wish to go and play through encounters, whether combat with chorts in the 3D mode of conversations with villagers (or chorts) in the 2D mode. By going to different locations, Vasilisa completes her objectives and also collects information in the form of bailichkas (little folktales), encyclopedia entries, and folk songs that are kept in Vasilisa’s Onomasticon and which can be accessed and read at any time; there are dozens of these in the game and reading them can give you actual benefits by helping you answer questions and solve riddles correctly, gaining you more experience points.

The deck-building part comes in in the battles with chorts. As a koldunya, Vasilisa fights not with weapons but with magic, casting spells—zagovors—to either bless (heal or defend) herself or to attack her enemies. The zagovors come in the shape of cards which are sorted in a deck that is randomly drawn from in a set amount (a hand) each turn. Vasilisa uses the zagovors against the chorts, the chorts attack, a new round starts and a new hand of cards is drawn from the deck, with the previous hand shuffled back in. The zagovors/cards all do different things, deal different amounts and types of damage (or healing or defending), and create different effects (such as paralysis, waste, block, poison, etc.). The player has direct control over the composition of the deck and can select which cards, from a huge range, they wish to put in their deck. The deck is limited (between 13 and 33 zagovors) and your ability to put duplicate cards in the deck is limited (I believe no more than 4 of each zagovor). You can unlock new card types by defeating chorts and selecting one of three prize cards, and by breaking seals in the Black Book; each seal affords you access to new zagovors with increasingly complex effects and greater levels of power.

In addition to moving through the world, collecting knowledge for the Onomasticon, breaking seals in the Black Book, and building a deck of zagovors to strike fear into the heart of chorts and rival kolduni throughout Perm, Vasilisa will have to contend with sin and with a basket full of chorts that are her inheritance as a koldunya.

The basket, first. It’s called пестерь in Russian, which transliterates to pester’ (the apostrophe marks that the letter just before it is meant to be palatalized or “soft,” something we don’t do in English). This is a bit confusing, since the Russian word refers to a kind of small, woven basket specifically used for gathering mushrooms, berries, nuts, etc.—the kind of thing a rural Russian might very well have on hand, given the cultural obsession with mushroom foraging—and has none of the connotations, at all, of its homophone in English, the verb “pester,” i.e. to annoy or bother (which in Russian is докучать/dokuchat’ or донимать/donimat’). But the homophony is serendipitous, because the basket of chorts is in fact a pestersome thing!

In addition to doing magic through spells (zagovors), kolduni accomplish things by bending lesser spirits to their will; in other words, over the course of their lives, and as they grow in power, a koldun(ya) attracts to it a retinue of spirits/demons/chorts who serve the koldun(ya). In old age, the koldun(ya) either passes these on to a successor or, well, they’re killed by their chorts whom they must keep perpetually busy (idle hands…). Vasilisa, then, inherits chorts from Egor and gains more as she grows in power and renown; she must assign them to “tasks” around the uyezd, such as blighting a farmer’s crop or killing a cow or causing a rash of fevers or burning down a barn—the very things that people, who believe the world is inhabited by spirits, blame on spirits! If Vasilisa does not assign the chorts in her pester’ to a task (which can take 1-3 days to complete), then the chorts weaken her health and make it harder for her to battle other chorts. If Vasilisa does assign them tasks, she accrues sins for the evil deeds she has sanctioned. Vasilisa is thus pestered by her pester’.

The sins, now. In addition to those gained by sending out chorts to do evil deeds to prevent the negative effects of their pestering habits, sins can be gained throughout the game in all manner of ways, typically through choices Vasilisa must make. Actions can either be sinful or absolve Vasilisa of sins. This is a version of the morality systems that are so common in RPGs today and it ultimately has very little immediate effect on gameplay. Unlike keeping chorts in your pester’, the sins themselves don’t provide negative effects to the gameplay. You can also absolve yourself of sins through good actions. The game tutorial suggests that accruing sins will change dialogue options and perhaps the ending of the game; I played as a largely good person, accruing less than 50 sins in the course of the game, and I haven’t been able to get a sense of how the ending might change if I’m “evil.” In the end, sins didn’t seem to matter ludically, though narratively the sins are I think quite important and reveal much about how this short indie game is thinking through morality, religion, folk belief, and histories of cultural contact and colonization in fascinating and exciting ways.

Chorts, History, and the Specters Haunting Black Book

Black Book is a game that is hyper-conscious of the social world Vasilisa inhabits, both its class and ethnic hierarchies, but also its moral reality as exemplified by the sins and the chorts that are so often the source of Vasilisa’s increased sin count. The game proposes that Vasilisa’s actions, all the more so as a person with great knowledge and therefore great local power, with the ability to affect the lives and livelihoods, even safety, of villagers throughout the uyezd—so much so that Black Book regularly translates the Russian words koldun and koldunya as “knower,” emphasizing knowledge as literal power—greatly affect people, positively and negatively. This is not surprising; after all, Vasilisa inhabits a world where people not only believe that an offhand remark could see your child get lost in the forest, cause your neighbor to miscarry, or make your grain stores rot, but where these things actually happen and are caused by spirits and by those who manipulate spirits.

The game uses the word chort, a word variously translated as demon or spirit, but it has much in common with the ancient Greek term daimon from which we get demon today (also the source of Philip Pullman’s dæmons)—only in ancient Greek, this meant all of the spirits of the world, whether the spirit of a tree or a forest or a river. As Black Book unfolds, as we encounter more and more chorts, we see a similar, multivalent and elusive meaning at play. Spirits are not necessarily evil, though like people they may do evil things, and many spirits we encounter descend from an older, pre-Christian folk tradition understood to be pre-Slavic and thus Permian (sometimes called Chud’ in the game, a medieval reference). The spirits and folkways of understanding them have been overlaid by the Orthodox Christian theology imposed by Russian colonialism on the region, such that the Permian world of spirits is now mixed with that of Christian demonology, and also with Slavic folk beliefs about both spirits and demons. Thus, chorts are read variously by villagers as folk spirits and/or demons from Hell, depending on the person, the circumstances, and the chorts’ actions. It’s a complexity full of wonderful contradictions that are left untangled. The palimpsest of beliefs at work in Vasilisa’s world come from three different cultures—the Permian, the Slavic, and the Christian—that forcibly merged over hundreds of years and are so muddled that they naturally coexist in people’s lives (as the very real bailichkas we collect demonstrate) in contradictory ways.

This layering of histories of place, people, culture, and belief—rending an often messy, internally inconsistent world of folkways and beliefs that is more true to the real world complexities of cultural change than the often cut-and-dry, highly systematic, supposedly internally consistent histories and cultures of so much secondary-world fantasy worldbuilding—is a major theme of the game. Ancient spirits, once revered as deities by the Indigenous Komi and Udmurts, and their Chud’ ancestors, are everywhere in the world of Black Book, often transformed by their contact with Slavic and Christian belief systems into new manifestations. Sometimes they forget entirely who and what they were, as in the case of Proshka.

The chort Proshka takes the form of a black cat and is one of several allies Vasilisa acquires in the course of the game. The three allies—Proshka, Levonty (the flying skull of a former koldun), and Karnysh (a leshy in raven form)—have side stories that are largely unrelated to the main narrative and are optional, but highly rewarding for how they flesh out the storyworld. Proshka is first encountered as an ikota, a very Christian type of chort that possesses people and makes them do strange and violent things. When exorcized, Proshka admits he became an ikota to escape his isolation after the church he inhabited (as a different kind of chort, one who protects the grounds of a church) was abandoned. But over time we learn he was only a churchyard chort because the church was built over the land that was his earlier domain, and that he was once a primordial pre-Slavic Permian deity, Voypel, the North Wind itself and god of night. Upon regaining knowledge of his identity and stripping it of the vestiges of Russian cultural colonialism and Christian faith, Proshka-Voypel changes form from a rather normal-looking black cat to a floating white cat with three glowing eyes.

Black Book decolonizes Russian folk beliefs, showing how Slavic and Christian ideas exist(ed) side-by-side with and were often violently imposed on older, pre-Slavic and pre-Christian cultures—which remain an important part of Russian life outside of the more homogenous European urban centers of the nation’s west, as Morteshka is arguing through its games. Non-ethnically Russian peoples, cultures, languages, and ways of living have coexisted with and often been oppressed by ethnic Russians, the Russian (and Soviet) state, and Orthodox Christianity since the beginning of the Russian imperial project in the late Middle Ages. As the Proshka-Voypel storyline demonstrates, history is everywhere in Black Book—itself a period narrative that is told as a story of “long ago,” a time when kolduni and chorts were still readable as “real” in Russian life. But, even in its world of 1879 Russia, and more specifically of an ethnically mixed, rural governorate (krai) far from the imperial metropoles, things are changing. Life is not static and unchanging, even in the Permian boonies.

A major antagonist in the game is Alexander, a noble who is interested in science, technology, politics, and what he sees as the quaint folk traditions of the uneducated rural peoples. Vasilisa first meets him in chapter two when she’s dispatched to a salt factory to stop a vodyanoy (water spirit) and a rusalka (mermaid) from interrupting their work. Labor, its ethical practices, and technological change are at the forefront in this chapter, and it brings into further contrast the tensions between the encroachment of modernity (here understood as new technologies, like the telegraph) into rural Perm and the local people and their folk traditions. As Vasilisa solves who is behind the clipping of telegraph wires (local people who fear it, and who try to cover their tracks by making it look like the work of a vengeful chort, thereby using the specter of folk tradition to combat new technologies), she is increasingly annoyed by this Alexander character who doubts the reality of her magical abilities and turns his nose up at the peasants who believe in chorts.

But we later learn that Alexander is in fact a powerful koldun himself. He wants Vasilisa’s Black Book so he can break the seals to wish for a new world order in which chorts are the slaves of humanity, doing all physical labor for us. In other words, Alexander wants to bring about a “chortocracy,” as he calls it, in which humans are freed from labor by the “machine” of enslaved spirits (who, we know from the Proshka example, aren’t necessarily evil), allowing humanity to live in utopian bliss. This idea is timely for its late-nineteenth century setting, since the last decades of the century period saw a proliferation of utopian novels and political theorization, including the groundwork for the many movements that exploded together in the Russian Revolution. Alexander’s chortocracy offers a critique of technological change and social revolution predicated on the oppression of entire classes of beings, and is at odds with the equally violent vision of another antagonist, the Spinner, who wants the Black Book so she can eliminate all chorts completely from existence—in other words, genocide.

Rural, underdeveloped, resource-rich regions like Perm were significant to the world-historical changes Russia went through in the 60 years between the abolition of the serfdom of peasants in 1861 and the rise of the Soviet Union in 1922 after decades of less and more successful revolutions. These changes, and especially the social anxiety and cultural shifts that followed from Russia’s transition in less than a century from a near-medieval feudalism into a globally competitive industrial modernity that put the first human in space, are woven throughout the story of Black Book. Like the best folk horror, Black Book is hyper-aware of how its narrative and thematic emphasis on folkways, on magic, on “older” modes of existence, on nature, and so on are being used to critique later and contemporary sociohistorical developments, particularly the violent industrial modernity of the Soviet Union and its very different history of oppression that built on the violence of Russian imperialism (what is sometimes called Russia’s “internal colonization” of its ethnic territories). In fact, Vasilisa meets multiple chorts who prophesy the coming of a great age of death, disruption, and upheaval to Perm’s countryside, a vague notion that modernity itself or something more specific is coming, say, the Russian Civil War, during which as many as 10 million people died. But Black Book’s power, its brilliance, lies in its ability to be read in multiple ways, to resist a totalizing vision of the past. Like these chort prophecies, like the ever-changing identities of the chorts themselves in response to shifting beliefs about them, Black Book is neither simple nor singular.

Though it is small and short when compared to the sprawling excesses of AAA RPGs, Black Book is dense, complex, and enlivening. Players are not given an open world, but are instead encouraged to seek knowledge, to collect bailichkas, songs, and encyclopedia entries, and to learn from villagers and chorts and kolduni about the many belief systems interacting in everyone’s everyday lives. What does one have to do to use a banya without being cursed by a bannik? How can one travel safely through a forest, a crossroads, or by a graveyard? What rituals should a hunter perform to ensure their protection in the forest, from leshy and wolves alike? What offerings should a farmer leave the spirits of the field to fulfill their supernatural contract and ensure a good harvest? These are things we can learn in the game, and which also highlight alternative attunements to the world around us, a vision of relation to the non-human that sees the world as vastly alive. And this is just a small fraction of what Black Book offers as it turns us, like Vasilisa, into knowers, as it interpolates us into its system of sins and absolutions, as it makes us care for Nikolay and Proshka-Voypel and even, perhaps, misguided Alexander.

Black Book is that rare video game that, to me, opens up like a novel, that offers such a seemingly real and total world that I cannot help but want to know more, to be awestruck, and to want to write about it. And I haven’t even talked about Vasilisa’s journey into Hell, her escapades in the hierarchy of demon princes, her confrontation with death, and her defeat of Satan himself…

From Vilgort with Love

Black Book took me about 13 hours to play on the easiest setting, and with me doing all of the side quests, collecting and reading everything in the Onomasticon, and pursuing every dialogue opportunity and option. I played on the easiest setting in order to focus on the story and not get bogged down in the mechanics of the cards. I built a deck that focused purely on dealing immense amounts of damage and, as a result, I never lost a battle. Players can also choose to skip any battle they wish, for the sake of focusing even more on the story, and there are occasional puzzle battles that have to be won with a preselected deck against tricky enemies; these are fun, but can get annoying if you’re in the midst of a particularly exciting chapter, and they can also be skipped.

That Black Book was made by a team of c. 5 people, occasionally shows. Geniuses as they are for having built such a thematically complex and narratively rich game, there are aspects of the game that are less than ideal or feel underbaked. An easy target of this criticism, for me as someone who can read and understand a little Russian, is the irregular transliteration of Russian terms into English and the occasional awkward translations, phrases, and uses of terms (often idiomatic) that don’t quite sync up for Anglophone players. There are also awkward gameplay elements; for example, movement in the 3D environment is incredibly wonky, even difficult at times. And the deck-building system is perhaps too robust for the time allotted to the use of its robustness. What I mean by this is that, with each broken seal, the cards/zagovors and their effects—and how those effects interact—get more and more complicated. The last few chapters go by rather quickly, so that the new complexity offered by later zagovors is not able to be easily understood, much less appreciated. What’s more, there’s very little incentive to understand the complex effects of later zagovors, since from c. the third chapter onward you gain access to cards that deal wallops of damage; with few exceptions, there’s no need for anything but the blunt hammer of high-damage zagovors.

These issues are all, for me at least, minor. Some reviews I’ve read gave low marks to the game because of its repetitiveness in combat and the somewhat indecipherable complexity of later zagovors and effects, though it’s clear that most such reviewers are little taken with the expansive storyworld Black Book opens up and care mostly about the game qua game. But what mattered to me most was the narrative and the storyworld—and how they were brought to life visually and audibly. For me, then, there is nothing like Black Book that gives such depth, such illusion of reality. While 100+ hour AAA titles like the recent Assassin’s Creed entries or Skyrim or Baldur’s Gate do build compelling historical and fantasy worlds, they still feel artificial, repetitive, and unlived in compared to Black Book, which practically bursts with life. For all its richness, I could write a book about this game!

Perhaps this is an effect of the very real bailichkas and folk-knowledge Vasilisa gains throughout the game, which were recorded by anthropologists, such as consultant Konstantin Shumov and in collaboration with the Perm Museum of Local Lore, from the mouths of real people who believed what they were saying, or at least for whom the stories had deep local and personal meaning. Perhaps this is an effect of the soundscape created by Mikhail Shvachko’s inimitable soundtrack, which is easily one of the best video game soundtracks of all time, and which includes striking, haunting, beautiful folk music recorded in Perm by local singers (my favorite, “Little Fir Tree,” can be heard here). Perhaps this is because the lives of the villagers encountered throughout the game are both mundane but also bound up in complex magical and religious systems of folk knowledge that the game encourages players to learn, and which, even by the end, we are left feeling as though we’ve merely scratched the surface. It is all of these things and more. If you’re not a gamer, I encourage you to watch a playthrough of the game.

Black Book is thick with culture and history, with memory and belief; beautiful, heart-breaking, entrancing, and more, it is at once intoxicatingly real and hauntingly fantastical. It is, to me, a masterpiece of folk horror and of Eastern European fantasy that will sit with me for years to come.

One thought on “Playing “Black Book” (2021)”