The Last Unicorn by Peter S. Beagle. 1968. Ballantine Books, Feb. 1969. [My version: Fifteenth Printing, 1979]

This essay is part of Ballantine Adult Fantasy: A Reading Series.

Table of Contents

Prelude: The Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series

Beagle and the Coming of The Last Unicorn

Reading The Last Unicorn

Heroism, Romance, and Beagle’s Metafantasy

A Good Age for Unicorns?

Postlude: The Sound of a Spider Weeping

Peter S. Beagle’s The Last Unicorn is a supremely beautiful, memorable, and critically energizing masterwork of fantasy. The novel manages to be at once profound and silly, wholly familiar in its embrace of fairy tale and heroic romance, flirting tauntingly with high fantasy, and yet is unfamiliar in its odd, metafictional mixing of materials, sources, and influences. Published a decade ahead of the fantasy boom that would start in the late 1970s, The Last Unicorn is—as Timothy Miller describes it in his excellent critical companion to the novel—“an early comic metafantasy that seems to anticipate much of the history of mass-market fantasy to come” (8).

It is a wickedly artful novel that appears early in the history of genre fantasy and yet reads almost as a retrospective on a well-established genre, as though it is reflecting on decades of lengthy series of doorstop novel after doorstop novel drenched with Tolkienian influence. Indeed, Farah Mendlesohn and Edward James describe it in A Short History of Fantasy as “the first of an emerging counter-narrative to the oncoming Tolkien tsunami” (89), by which they mean fantasy series overly/heavily influenced by Tolkien. In many ways, The Last Unicorn is a response to Tolkien by an author who both deeply loves The Lord of the Rings but has little interest in the arch or the arcane, or in their imitation. The novel feels decidedly American, decidedly of the 1960s—even set, as it is, out of time in an unmapped, unknowable world of unicorns, talking butterflies, unnamed kingdoms, hordes of princesses, heroic quests abounding, and would-be Merry Men who pretend to great deeds in order to make their way into folk ballads. It is a stunningly beautiful novel of time and memory, of seeming and being, of the human and the immortal, of fantasy and comedy, of history and, more importantly, how to live in its wake.

In nearly 60 years, The Last Unicorn has never gone out of print. It regularly sells tens of thousands of copies a year, has been translated into dozens of languages, has been adapted into an animated feature film with art by a Japanese production company that would later form a good portion of Studio Ghibli and a songs performed by the British rock band America (aptly enough), and has practically defined Beagle’s career as a writer. It’s also a great place to start something I’ve been meaning to for far too long.

Prelude: The Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series

That we might read The Last Unicorn in the tradition of, and certainly in response to, The Lord of the Rings makes good historical sense (and a lot of textual and biographical sense, too, as explored thoroughly in Miller’s critical companion). After all, The Lord of the Rings was a major event in the emergence of genre fantasy—that is, of fantasy as a discrete category that readers, publishers, marketers, bookstores, authors, and critics alike could recognize, respond to, conceptualize, argue about, etc. Of course, fantasy novels and stories, and more so the elements (such as traditional myths and folktales) that would become part of the genre fantasy explosion in the postwar period, had long pre-existed Tolkien (by how much is a matter of significant debate that I have my own strong feelings about) and Tolkien cannot be said by any stretch of the imagination to have “invented” fantasy. (The search for “firsts” is always a losing game and says more about the narrative one wants to tell about a genre, than about the genre itself.) But what the postwar period witnessed, thanks in large part to Tolkien’s belated popularity in the mid-1960s, was a wholescale reorientation of terminology around the many things that would come under the banner of fantasy and a process of canonization that brought into scope the shape and meaning of this newly identifiable, clearly nameable, and mass-marketable genre. We call this complex and often uneven literary, cultural, and historical process the “formation” or “emergence” of a genre, since these terms point to the always active process of a genre accreting into being and changing.

Although The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings had been previously published in the U.S., the former in 1938 and the latter in 1954, both in hardcover, they shot to popularity when Ace published their unauthorized, “pirated” editions of The Lord of the Rings in early 1965 and when, after much legal wrangling, Ballantine published the authorized editions of The Hobbit and the trilogy in late 1965. (How, exactly, things progressed so quickly, in the course of seemingly under a year, I have no idea; the publisher in me would love to read a blow-by-blow history!) The Ace editions alone sold 100,000 copies in just a few months and Ballantine’s editions proved such bestsellers that they decided to publish The Tolkien Reader, comprising earlier poems and shorter works (like Tree and Leaf, Farmer Giles of Ham, and The Adventures of Tom Bombadil), in late 1966.

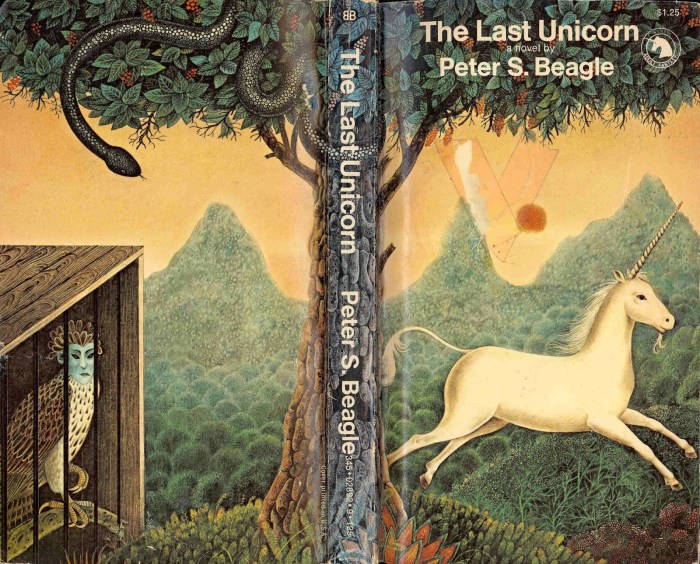

Seeing the potential of fantasy as a market category—that is, “serious” fantasy for “adults” —Ballantine republished a dozen other fantasy novels over the next three years: reprints of E.R. Eddison and David Lindsay (themselves influences on Tolkien), various other bits and bobs by Tolkien, Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast trilogy, and the first two novels by Peter S. Beagle. All of these were mass market paperbacks with lush wraparound cover art by painters like Gervasio Gallardo, Robert Pepper, and Barbara Remington that blended the modern and the faerie, modernism and the emerging postmodern, in ways that make these early fantasy paperbacks wonderful collectors’ items today, and which no doubt established a visual cache for the emerging genre in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The small success of these novels encouraged Ballantine to start its own line of fantasy books under the editorship of Lin Carter, who was mostly known at that time for pulpy stories in the vein of Lovecraft and Howard, but who also brought a deep knowledge of the history of fantasy to his work for Ballantine, as evidenced in both his lengthy introductions to each book and his three book-length works of criticism published by Ballantine (one on Tolkien, one on Lovecraft, and one on fantasy generally).

This collaboration between Carter and Ballantine became the Ballantine Adult Fantasy (BAF) series, which published 65 books—mostly novels, but a handful of anthologies, too; six or seven of the novels were original to the series—between May 1969 and April 1974, in addition to the 18 books published between August 1965 and April 1969, including Tolkien’s novels, all of which Carter later dubbed the “preface” to BAF. Beagle’s The Last Unicorn, republished in paperback by Ballantine in February 1969, after its initial hardcover publication a year prior, was the first to have “A Ballantine Adult Fantasy” emblazoned on its cover, though it was not officially part of the series, which began several months later with a reprinting of Fletcher Pratt’s The Blue Star (1952). The idea of the unicorn as emblematic of fantasy further defined the BAF series through the use of a small unicorn’s head as the series colophon, which appeared in a circle in the top right-hand corner of each novel’s cover (and on later reprints of some of the pre-BAF novels, like Peake’s trilogy). BAF’s feast of novels, anthologies, and Carter’s works of criticism helped create and feed the new hunger for fantasy.

By the end of the 1970s, fantasy was in. What steadily grew in the wake of Tolkien, throughout the Ballantine Adult Fantasy years, through the efforts of savvy publishers who picked up and paperbacked novels like The Last Unicorn and Ursula K. Le Guin’s A Wizard of Earthsea for fantasy-hungry acolytes, exploded after the blockbuster year 1977, which saw the publication of, among other things (e.g. Stephen R. Donaldson’s Lord Foul’s Bane), several groundbreaking novels—J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Silmarillion (edited by Christopher Tolkien), Piers Anthony’s A Spell for Chameleon, Terry Brooks’s The Sword of Shannara—that put fantasy back on the bestseller list and made the culture at large realize the fantasy phenomenon wasn’t a one-time thing. (Not for nothing, Locus began their first poll for a best fantasy novel award in 1978, recognizing the previous year’s accomplishments and awarding The Silmarillion.) Unsurprisingly, Anthony’s and Brooks’s novels were published by Ballantine’s new science fiction and fantasy imprint, Del Rey. Most publishers had a fantasy imprint or published the genre regularly alongside their science fiction. As Dennis Wise has shown, fantasy, especially published by Del Rey, sold very well, often better than science fiction—a fact that has led many who remember the period to decry Ballantine/Del Rey’s negative influence on the field, for supposedly “dumbing down” fantasy.

By the end of the 1980s—during which fantasy paperbacks invaded every (strip)mall in America as big-box bookstores like Borders, Barnes & Noble, and B. Dalton sprung up in every suburb; and during which fantasy became a contender in cinemas through both live action and animated high-budget fantasy film releases; and during which Dungeons & Dragons became a household name, spread all the more fervently by the Satanic Panic—fantasy was irrevocably bound up with popular culture and had wormed its way into every facet of the creative industries, taking root in, thriving among, and re-enchanting readers, audiences, and players generation after generation.

We live today in the shadow of the mass market paperback era. Tolkien’s popularity in the U.S. in the early 1960s planted the seed for widespread reader interest in fantasy as a discrete category, one that publishers, authors, readers, and critics alike could now see the shape of (for better and worse), and which they would quickly build on by both retrospectively bringing earlier books into the fold of fantasy and publishing new books to help flesh out the skeleton of the genre. This didn’t come out of nowhere, of course, since there was a rich but small tradition of fantasy novels published mostly in hardcover and in small print runs throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and there was also the tradition of weird fiction and sword and sorcery that outlived the pulps and saw its own renaissance in the late 1950s/early 1960s, and much more besides (e.g. the translation and widespread accessibility of Arthurian and other European myth traditions in the Victorian period, the fairy tale tradition, the golden age of children’s literature, much of it fantastic, and so on)—and someday I will write a book about this decades-long weaving of the genre tapestry—that came together in the 1960s and 1970s, along with multiple and sometimes contradictory countercultural responses to modernity (e.g. the arts-and-crafts movement, Renaissance faires, neopaganism, the folk music revival, etc.), and in doing so laid the foundation for, molded the shape of, and brought together an audience interested in the genre we now call, with much surety, fantasy. There was no one moment, no one book that brought it into being, but Tolkien played a key role and The Last Unicorn and BAF were part of the history of fantasy’s emergence as a modern genre.

For more on this, and especially on the complex role of BAF in shaping the canon—and therefore our understanding of and assumptions about the history—of fantasy, see Jamie Williamson’s The Evolution of Modern Fantasy: From Antiquarianism to the Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series. This is only one book on the topic and it is a truly incredible, thorough, and well-researched one; there’s not much else, though there are several competent histories of fantasy that address this period in some detail, including Mendlesohn and James’s A Short History of Fantasy, referenced above, with another by Adam Roberts, Fantasy: A Short History, out in April 2025. Still, the scholarly conversation about fantasy’s emergence as a genre (which is to say, its newfound salience from the 1960s onward), its relationship to the postwar publishing industry, and how we define and, more importantly, theorize fantasy is really only beginning. The field remains small and centered on a few monographs by fewer names. Essays on key texts like The Last Unicorn—the whole point of my Critic / Construct blog—are my way of moving toward saying something about all of this in bigger, bookier form. Getting to know the BAF series better is a small part of the larger project.

This is the first in a long line of essays I intend to write on the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series and its novels, which I’m calling “Ballantine Adult Fantasy: A Reading Series.” Admittedly, this first entry is out of order, but that’s my prerogative and I otherwise intend to read the novels in publication order, excluding the Tolkien books and continuing after this essay with E.R. Eddison’s The Worm Ouroboros. I am doing this because, while many scholars and critics write in passing about or reference BAF, few excepting Williamson give the sense that they have actually read it through—it is a big undertaking!—and I hope by reading it completely through, by considering the novels’ histories but also the context of their republication (that is, how they might have been read in the now of the late 1960s and early 1970s), and by taking into account Carter’s own critical introductions to each volume (that is, by reading Carter as a theorist of fantasy), I will have a better understanding of BAF as a genre-making project in this crucial period of fantasy’s emergence. I will try to make each essay an opportunity to flex my critical muscles, too, not just to research history and divulge plots, but to offer some contexts and arguments that might prove valuable down the road to myself and other fantasy critics.

All of this is just a beginning—who knows where it will lead, though I have my hopes, and hope, too, that I will have you as my companion.

Beagle and the Coming of The Last Unicorn

Peter S. Beagle was one of many names tucked away in the piles of books Ballantine churned out between 1965 and 1974 as part of BAF and its lead-up. Though most of Ballantine’s mass market paperbacks in this era were reprints of books usually decades old, Beagle was an outlier, having only just begun his career a few years prior. Indeed, it’s somewhat remarkable that he was reprinted alongside Tolkien, Eddison, Lindsay, and Peake, and the association almost immediately established his credibility as a “fantasy writer” in this newly visible mass market genre.

Beagle was a seemingly unlikely figure to become an early darling of the emerging genre and its newly forming canon, in large part because he was trained in the postwar institution of the creative writing program, where he was discouraged from writing non-realist fiction but pursued it nonetheless. A boy genius who graduate high school at 16 and published his first novel by 21, Beagle was also something of a beatnik, both in style and spirit, though he eschewed the term, and spent much of the 1960s traveling the country, and especially in California, documenting counterculture, such as the arts and crafts revival and the nascent environmentalist movement, through creative nonfiction.

Miller offers a thorough and illuminating overview of Beagle’s early career, as well as Beagle’s abiding interest in Tolkien, whom he read shortly after The Lord of the Rings’s initial hardcover publication in the 1950s. Tolkien’s works and especially their anti-industrial, anti-modern, and environmentalist themes surface again and again in Beagle’s reflections on his own writing and his experiences of West Coast counterculture, and these themes form the foundation of the tale told in The Last Unicorn, though Beagle does not by any means remain in Tolkien’s shadow and forges his own idiosyncratic, metafictional approach to fantasy that blends the countercultural elements he was absorbing, the literary pretensions of the Program Era, and the playful animosity to tradition of the beatniks and the emerging postmoderns.

Beagle’s first novel was a very different kind of fantasy, a kind of comic ghost story and meditation on death. A Fine and Private Place debuted in hardcover from mainstream publisher Viking Press in 1960, with a neat little cover—the title written in elegant cursive above a small, painted scene of a dirt road hedged by flowers, and a red paper heart with a tear in it discarded on the road, at the center of an otherwise all black cover—that marked it more as a (frankly boring-looking) realist romantic drama than a fantasy of any sort. It was later reprinted by Ballantine as part of their search for more “adult fantasy” novels like Tolkien’s, Eddison’s, Lindsay’s, and Peake’s. It appeared as a preface novel to BAF in February 1969 alongside Ballantine’s mass market edition of The Last Unicorn, just three months before the series officially launched.

A Fine and Private Place was written when Beagle was just 19, published when he was 21. In the intervening years between his first and second novel, he traveled the country by scooter, wrote nonfiction for magazines, lived the life of a “bearded non-beatnik” in the heart of the counterculture, and published a travelogue of his journeys, the first of several such reportages about changing culture in 1960s–1970s America. Beagle tried to write another novel, titled The Mirror Kingdom, that was rejected by Viking, and spent 1962–1963 writing the first draft of a much different early version of The Last Unicorn, set in 1960s America, before giving up on what felt like a dead end. That manuscript was later republished in an annoyingly difficult to find, out-of-print edition first published by Subterranean Press (2006) and later Tachyon (2018). Beagle picked up the story again in 1965 and spent two years writing The Last Unicorn, which sold to Viking.

Viking published The Last Unicorn in hardcover in 1968. It was positively reviewed in literary fiction circles and from the beginning was compared to Tolkien. The novel was understood as speaking to the postwar generation, the kids now reading Tolkien in paperback, wearing “Frodo Lives!” pins, discussing if not going to anti-war marches, and spinning Bob Dylan vinyls. The novel was tepidly received by fantasy critics, who seemed less enthusiastic about it than their comrades in the literary magazines. As Miller notes in his critical companion to the novel, this difference in reception between literary and fantasy critics and scholars alike is a rather ironic inversion of the argument long and loudly made by fantasy scholars who bemoan that the Literary Elites don’t take fantasy seriously.

A year after its hardcover publication, The Last Unicorn was published in mass market paperback by Ballantine in February 1969. “A Ballantine Adult Fantasy” was emblazoned on the first edition and front matter copy compared the novel to Tolkien and Lewis Carroll, claiming it as part of “the tradition of fantasy.” With this move, The Last Unicorn gained a new and much bigger audience. No doubt the choice to publish The Last Unicorn was made in part because of the already prevalent comparisons of the novel to Tolkien, but also because Beagle was familiar to publisher Betty Ballantine and BAF editor Lin Carter. Beagle had published a critical essay on The Lord of the Rings in Holiday Magazine that was republished as the introductory essay to Ballantine’s anthology of minor Tolkien texts, The Tolkien Reader, in 1966. The bio given for Beagle in that book is telling, since it identifies him as a nonfiction writer, traveler, and author of an “extremely well received” novel (A Fine and Private Place). Fantasy was not yet part of his writerly persona, at least not explicitly, but the publication of The Last Unicorn two years later proved a boon to both Ballantine and, through his earlier familiarity to them, to Beagle as well. Thus was The Last Unicorn paperbacked and Beagle yoked to (the narrative of) the emergence of fantasy as a mass market genre.

As an aside, the incredible, haunting Ballantine cover—a chubby unicorn awkwardly suspended mid-jump before a forested mountain range, a red sun coloring the sky pink; the eerie, blue-faced harpy Celaeno caged here forever by Mommy Fortuna; and a serpent slithering in the canopy of a red-fruited tree that spans the wraparound cover, both an allusion to the serpent of Genesis and to the world serpent Jörmungandr also captured in Mommy Fortuna’s carnival—was painted by Spanish artist Gervasio Gallardo. Gallardo would become a staple artist for BAF. Gallardo’s covers are noted for his incredibly odd, lush scenes that capture multiple elements of each BAF book in one semi-narrative scene, juxtaposing elements in careful composition and often with stark color contrasts. The figures in his cover paintings are always distinctly inhuman, unfamiliar, but never fully monstrous, making him a perfect fit to cover The Last Unicorn. Gallardo’s covers lead to“incandescent otherworlds,” in the words of writer S. Elizabeth, and expertly complement the work BAF was doing to create not just a canon of fantasy but a feast of ideas, symbols, and generic shorthands. What I would give to see the original Gallardo paintings for this series!

Reading The Last Unicorn

The Last Unicorn is an achingly beautiful book and marks Beagle as one of the finest prose stylists to ever write in the genre. It is, consequently, slow reading precisely because the novel must be savored. It is rich with metaphors that come as if from nowhere, so seemingly unfitting but on reflection absolutely true are the comparisons, unlike anything else, and it is verbose with descriptions that carry the sense of things more than the look of them. Beagle as a masterful artist blends the arch and the mundane with every sentence, and remains ever playful except where the unicorn is concerned. She remains aloof, unknowable, truly distinct from the mortal, always-dying people around her; cut off from their mortality, she is a personification of nature (yet not reducible solely to that), beyond the human and our conceptions of right and wrong, though she is shaped by the concepts of good and evil, of purity and otherwise, of youth and age and agelessness. She becomes a mess of symbolisms which characters (and readers) who encounter her—or wish to—charge her with.

Beagle brings his odd, comic world to richer, dearer life in a mere 250 pages than any doorstop obsessed with worldbuilding could ever hope to achieve. There is vitality here; it is not familiar, by any means; it is too idiosyncratic and fae; but Beagle envelops the reader in its temporary logics and truths, its fancies and myths—which are here one and the same. Nearly every page of my copy is marked with vertical pencil scratches running the length of several lines of text, graphite brackets demarcating entire paragraphs, and half-readable scribbles at the bottom of every other page—the only space available in the skint margins of the mass market format—charting out themes and hazarding connections across the cognitive map of Beagle’s faerieland. To be sure, there are clear themes and arguments made in the novel about fantasy, romance, heroism, power, desire, greed, memory, duty, and much else besides running throughout the book, though they are not all as easily pin-down-able as some scholars suggest. I have tried, in the following, to hold myself back from making too many hard-and-fast claims about meaning in a novel that endeavors to elude such capture.

The narrative of The Last Unicorn concerns a question: is she the “last” unicorn and, if so, what has become of the unicorns? The answers are the object of a quest, which seems not as grand, not as starkly universal and apocalyptic, as that of Tolkien’s Fellowship, and it certainly lacks the grand battles that have come to characterize epic fantasy, but it is just as consequential. Indeed, the quest leads to dramatic personal changes for all characters involved, as well as to consequences for a world that has allowed unicorns to disappear (and which sees them return). The narrative expertly uses just a few characters—Schmendrick, Molly Grue, Prince Lír, King Haggard, not to mention fleeting but no less important personae as Mommy Fortuna, Mabruk, and the talking skull—to map a heady brew of emotional, social, political, and literary concerns that bubble up from the cauldron of its pages.

The question of the unicorns’ disappearance from the world—that is, of the enchantment and beauty of nature having been driven out of it—is raised when, after a fairy-tale-like introduction— “The unicorn lived in a lilac wood, and she lived all alone”—the unicorn overhears two hunters roaming her forever-spring domain and the older of the two declaims that this must be the abode of the last unicorn, for the animals here cannot be hunted and the weather never sours. This revelation shocks the unicorn and, after a dizzying conversation with a beatnik butterfly, who confirms the fate of the unicorns (“They passed down all the roads long ago, and the Red Bull ran close behind them and covered their footprints”) in a fleeting moment of seriousness, she leaves her wood in search of her kin and the Red Bull.

The narrative is split, by and large, by the unicorn’s first confrontation with the Red Bull halfway through the novel, which leaves her utterly changed—emotionally and physically. Before that crux, though, she is joined by a magician (Schmendrick) and a cook (Molly Grue) as companions in her journey, during which she is captured and put on display in an illusory menagerie by a carnival witch (Mommy Fortuna) and encounters a range of humanity from peasant villagers to bored princesses to bandits. When she finds and confronts the Red Bull in the dying lands of King Haggard, the unicorn loses and is near to being driven away as all her kin were, but she is instead transformed by Schmendrick into a human. In that form, as the Lady Amalthea, she is accepted into the cold, unwelcoming hospitality of Haggard’s castle, where she struggles to remember her true self and not slip into the tempting oblivion of mortality, represented most poignantly by her courtship with Prince Lír. With the help of Schmendrick and Molly Grue, though, she keeps to her quest, finds the unicorns held captive in the sea by Haggard and the Red Bull, and through the sacrifice of Lír (who is later revived) is able to confront again and finally defeat the Bull, driving him into the sea and restoring the unicorns to the world.

This is an overly brief summary that glosses over much, but the narrative is widely known and a great many scenes in the novel—from the beatnik butterfly to Mommy Fortuna’s Midnight Carnival to the villagers in Hagsgate to the final confrontation with the Red Bull, and more—have been regularly discussed in scholarship and criticism since the 1970s, so detailing them overmuch without having anything significant to add seems pointless. Unlike the vast majority of fantasy fiction, there is not a dearth of critical discussion about The Last Unicorn. Indeed, the few dozen articles and sustained discussion of the novel in a handful of monographs constitutes “a lot” in the small field of fantasy studies. Miller’s short monograph expertly summarizes and expands the extant critical conversations about the novel and the major themes they have mined. These include themes of time, (im)mortality, and memory; magic and its use as a commentary on creativity, especially with regard to the “true magic” of being able to create something, as opposed to merely imitating it (what I call the theme of seeming versus/and/or being); Beagle’s deployment of metafiction and a sincere form of metafantasy that treats fantasy earnestly, but plays with it nonetheless; and, of course, source studies that delve into the literary, cultural, and historical antecedents of unicorns, bulls, magicians, Mommy Fortuna’s menagerie, and more. These are but some of the questions regularly explored in the scholarship.

The beauty of criticism, though, is that the conversation never ends, and that’s truer especially when the text is this moreish. The Last Unicorn is a magnificently rich treat for the critic and much can still be said and argued about it: there can be no beating a dead horse when that horse is in fact a unicorn and immortal. The novel offers so many avenues for critical investigation that my own notes run to several thousand more words than I have written here. So—for the sake of brevity in a piece that has already thrown brevity to the wind—I will focus on just one major thematic concern of the novel that I think holds particular weight, and to which I might add some useful commentary, especially given the novel’s place in the history of fantasy fiction in this crucial period of emergence. Though, as will become clear, and as Miller so deftly shows, the themes surfaced by the novel are not easily reducible to a single word or idea, but are instead the locus of thematic clusters that radiate out into still others. Beagle carefully imbricates the novel’s many discourses such that each is a patchwork of ideas threaded to the whole. Stars in a galaxy, galaxies wheeling through a cosmos.

Heroism, Romance, and Beagle’s Metafantasy

The Last Unicorn is structured around a quest. In its uneven unfolding, which lurches about across a map that is never charted for the reader and at timescales that are never exactly clear, and with odd twists and turns that feel both familiar and jarring, the novel resembles as some have noted a fairy tale but reads more, to me, like a medieval Arthurian romance—say, a reworking of one of the cycle’s episodes by Chretien de Troyes. It is also very much in the vein of Tolkien’s grand quest to defeat evil or, to put it another way that respects Tolkien’s own theories of fantasy, to restore the world and thereby reenchant it. Beagle’s text is aware of all of these resonances, and more; his novel offers a sincere quest of recovery that seeks to reenchant the world by restoring the unicorns. For Beagle, the quest and the heroism of its aims are fundamentally important to the novel, and indeed to fantasy storytelling, and they are elevated in the novel through their critique. The Last Unicorn gives us heroic(ish) figures in the form of Schmendrick, Molly, the unicorn, and, most paradigmatically, Prince Lír, even if it uses metafantastical means to mock them (excepting the unicorn). Importantly, though, as Miller argues, Beagle never mocks heroism itself, nor the idea of the quest of recovery, even if he critiques the means by which heroes make their mark. Such critique, which I’ll explore here, is deeply tied to the history of literary borrowings that evidences the “medievalizing” impulse of so much fantasy fiction, and to Beagle’s critical deployment of and play with the literary-historical elements that make up our collective understanding of quests and the romantic heroes who undertake them.

While at first the novel’s quest is led somewhat unusually by the figure of the unicorn—giving narrative agency to one more typically the object of a quest, as commented on in the unicorn’s glimpse of a princess and a prince boredly waiting about a forest glade for a unicorn to bless their coming nuptials—it is joined quickly by an equally unlikely duo of questers: Schmendrick and Molly Grue. The oddness of this grouping is part of the novel’s charm, with each character offering some insights into the deeper themes of the narrative. Schmendrick, for example, has been on a lifelong quest to perform true magic, for he is cursed with perpetual youth, a kind of grotesque immortality, until he is able to work real, powerful magic; he remains, therefore, mostly a carnival sideshow, yet he is cannily aware of the metafictionality of his situation and the story unfolding around them. Molly Grue, by contrast, is a figure of identification for readers, a woman whom the world has run roughshod over and who emerges into the quest able to become, finally, her own person. In Molly we can identify both our own critiques of the genre (the perhaps unrealistic hopes to be heroic ourselves or to be saved or courted by such heroism) but also our enduring desire for the reality of the fantasy story(world) despite our critiques. Importantly, both Schmendrick and Molly see in the unicorn, this quintessential figure of fantasy, some hint of their future transformation through the completion of the quest and therefore the fulfillment of fantasy’s narrative demands.

Only later, halfway through the novel, does The Last Unicorn “turn up a leading man” (109), as Schmendrick remarks, when he and Molly Grue discover that Prince Lír is a prophesied, curse-fulfilling figure: a child from the village of Hagsgate, the sole prosperous town in King Haggard’s land, who is adopted into the witch-built castle of Haggard as his own son and heir, “the one who will topple the tower and sink Haggard and Hagsgate together” (106). Schmendrick’s comical framing suggests The Last Unicorn is a tale not yet begun, and certainly not generically fulfilled, until Prince Lír shows up—and not just literally, as in, in the text, but as a subject of heroic importance suggested by his attachment to a prophecy of doom that conjures up the possibility of a grand climax involving the king associated with the object of the unicorn’s quest. In fact, princes and princesses are a dime a dozen in the world of The Last Unicorn, comically so, and we learn later the Prince Lír has already appeared before, as the bored prince engaged to the princess, described above, who reads magazines while awaiting her glimpse of a unicorn. Lír is as much pawn as agent of the formulas of fantasy, and he’s probably more the former than the latter, for as Schmendrick admonishes Molly when she asks about the logic of Lír’s chosenness, “Haven’t you ever been in a fairy tale before?” and shortly after clarifies, “Haggard and Lír and Drinn and you and I—we are in a fairy tale and must go where it goes” (108, 109). The unicorn, however, is not beholden to the logic of the fairy tale, and is therefore in Schmendrick’s reading of the novel he’s in, not a hero like Lír (Molly asks, indignantly, and rightfully so, “If Lír is the hero, what is she?” [109]), but something else and free from the generic logics of heroism and heroes. “[S]he is real. She is real” (109).

This notion of the unicorn being “real,” and beyond the logic of the story, is key to Beagle’s metafantasy in The Last Unicorn and is much remarked upon in the critical literature. As I noted above, the idea of seeming versus/and/or being, of the real and the unreal, is absolutely central to the critical work of the novel. It is interesting, however, that Beagle suggests the unicorn is real and therefore beyond storytelling logics and tropes and their demands, while at the same time acknowledging through the novel’s quest for recovery that she is indeed roped to its logics nonetheless. This is no doubt part of what Miller recognizes as Beagle’s tendency to wink at the structural and formal elements of genre and storytelling, while taking earnestly what they represent (see especially pp. 83–89 for Miller’s elaboration of how Beagle does this within the context of metafantasy). In this same way, Beagle plays repeatedly with the oddness, the incongruity, the simple strangeness of something like a unicorn, but takes her and what she means (as difficult to pin down as that is in this novel) so seriously. Beagle preserves a sincere love for and admiration of the genre and what it can do, while gesturing to its repetitive but useful—and therefore meaningful—structures, forms, tropes, traditions, etc. Taking this notion further, if the unicorn is indeed real, while being in a non-real story, and given Beagle’s penchant for questioning the forms but not their purpose or meaning, we might hazard here that Beagle is suggesting that fantasy as a genre is not in any important sense real, but that the fantasy of the genre as real, and everything the genre stands for and does for its readers and writers, most certainly is.

Because The Last Unicorn is a fairy tale and questing fantasy—that is, a romance—heroism and the concept of “leading man,” the hero, are central to the structural work of the novel. Once Lír graces the page as hero, as a romantic figure in the quest who will be crucial to the climax, the novel changes significantly. This change is also marked by the unicorn’s first confrontation with the Red Bull, her failure, and her transformation into a human. And further marked by Schmendrick’s second of three uses of real or “true” magic, which transforms the unicorn into Lady Amalthea, a power far beyond Mommy Fortuna’s illusions (notably his first use of true magic was the creation of a magnificently powerful and hyperrealistic illusion of Robin Hood, a myth even in this fantasy world). All three shifts in the narrative are important to the remainder of the story and indeed inform the final confrontation with the Red Bull, and the resulting restoration of the unicorns, in equal measure. And the first two are especially relevant to The Last Unicorn’s play with one of fantasy’s major literary and cultural antecedents: the romance—particularly the medieval romance of chivalry, the court, great historical matters, and, of course, quests.

Where the unicorn, a “real” figure of fantasy who nonetheless transcends the confines of the story, is turned into a noble lady, a princess of sorts, and is thus chained to the logics of fantasy and its romance, becoming the object of another kind of quest (the affection of a prince), the layabout Lír is transformed from a scrawny nobody holed up in a hated, hating castle, lazily courting some unnamed princess, into a hero of rather epic, if comic, proportions well beyond the norms of a medieval romance and indeed most fantasy fiction. In the span of a few pages from his introduction to the figure he thinks is Lady Amalthea, who “began to waken” something in him so that “he himself […] began to shine” like the unicorn-turned-lady (136), Lír becomes a great hero who bemoans that his many deeds—most recently the slaying and beheading of a fifth dragon—have failed to woo the lady.

The scene of Lír’s self-pitying search for meaning as the hero who cannot win the lady is a particular favorite of mine, and in one of the novel’s most charming chapters, which sees Molly Grue at work in the kitchen of Haggard’s castle, where characters visit her in turn and tell Molly about their lives and problems, and she gives succor and supper. (There’s also a talking cat—but thankfully not the pirate cat inexplicably added to the film adaptation) When Molly suggests to Lír that he change up his deeds, if Lady Amalthea doesn’t like dragon heads, Lír recounts his heroic accomplishments not as an epic tabulation of triumphs, but as a list of failures to impress Lady Amalthea:

“But what’s left on earth that I haven’t tried?” Lír demanded. “I have swum four rivers, each in full flood and none less than a mile wide. I have climbed seven mountains never before climbed, slept three nights in the Marsh of the Hanged Man, and walked alive out of that forest where the flowers burn your eyes and the nightingales sing poison. I have ended my betrothal to the princess I had agreed to marry—and if you don’t think that was a heroic deed, you don’t know her mother. I have vanquished exactly fifteen black knights waiting by fifteen fords in their black pavilions, challenging all who come to cross. And I’ve long since lost count of the witches in the thorny woods, the giants, the demons disguised as damsels; the glass hills, fatal riddles, and terrible tasks; the magic apples, rings, lamps, potions, swords, cloaks, boots, neckties, and nightcaps. Not to mention the winged horses, basilisks and sea serpents, and all the rest of the livestock.” He raised his head, and the dark blue eyes were confused and sad.

“And all for nothing,” he said. “I cannot touch her, whatever I do. For her sake, I have become a hero—I, sleepy Lír, my father’s sport and shame—but I might just as well have remained the dull fool I was. My great deeds mean nothing to her.” (149–150)

Lír’s deeds are a litany of fantasy quest cliches drawn from Arthurian romance, mythology, fairy tales, modern fantasy novels, and occasional jokes. They are magnificently many and varied. So much so that they verge into parody. Lír is too much of a hero. He’s a master of his trade. But unicorns have no need nor any concern for these things, these deeds which to humans might mean much but are adjudged by a unicorn either as pointless or uninteresting. Further, there is the underlying suggestion, totally in keeping with the genre, that a woman, and certainly a lady or princess, should in this courtly (story)world of romance give herself to any man able to perform even a fraction of such deeds. Beagle quietly surfaces the genre’s heteropatriarchal expectations. It’s worth noting, too, that throughout this scene between Molly and Lír, he repeatedly knicks his fingers on a knife while peeling potatoes—another subtle show of Beagle’s awareness of the gender dynamics at play in the story. (Curiously, gender doesn’t seem to be a particularly strong current in criticism of The Last Unicorn.)

The incongruity of Lír’s and the genre’s heroic ideals with the brutal, almost grotesque reality of such heroism is made plain in Lír’s account of his presentation of the fifth dragon’s head, “the proudest gift anyone can give,” to Lady Amalthea: “when she looked at it, suddenly it became a sad, battered mess of scales and horns, gristly tongue, bloody eyes” (149). In that moment of juxtaposition between fantasy and reality, in the presence of the still-not-totally-human unicorn-Amalthea (recall Schmendrick’s “[S]he is real. She is real” [109]), Lír is “sorry I had killed the thing” (149). In the face of unicorn-Amalthea’s failures to react in accordance with the genre, to succumb in a courtly manner to the hero’s accomplishments, Lír is left unsure how to bring the romance to a close, how to pursue the narrative impulses of the genre to their logical ends. But in being repeatedly denied the closure of the genre, Lír becomes an expert in its tropes.

Crucially for Beagle’s metafantasy, when Molly convinces Lír that heroic deeds won’t bring him the Lady Amalthea’s favor—he tries his hand at poetry, instead, seeking to embody the hero-poet-lover of nineteenth-century Romanticism—he decides not to give up doing deeds entirely: “I suppose I’ll keep my hand in [… . Y]ou get into the habit of rescuing people, breaking enchantments, challenging the wicked duke in fair combat—it’s hard to give up being a hero, once you get used to it” (169). This comedic, workmanlike treatment of the hero’s deeds as something so common in this fantasy storyworld that Lír can produce a laughably long list akin to a quest log from a 100+ hour fantasy RPG is key to Beagle’s metafantasy and his simultaneously critique of, and expression of love for, the fantasy genre. Importantly, this hero-as-job attitude is repeated at the novel’s climax, when Lír refers to the hero as “a trade, no more, like weaving or brewing.” The juxtaposition of heroing with weaving and brewing might seem at first to belittle the work of heroes, but Lír (and Beagle) is earnest in the comparison and respectful of the other arts: a hero is a skilled laborer, important to society, if not occasionally essential to it, and is no more nor less valuable than the other trades, who perform different and equally essential roles.

Unicorn-Amalthea is not moved by Lír’s many heroic deeds, for she remains in mind and spirit still a unicorn, albeit trapped in a body that can succumb to the very things that are her apotheosis: old age and death. But as Lír’s efforts show, in this new human body of a lady she is nonetheless interpolated into a particular set of generic demands whether she likes it or not (again, the novel makes clear its quietly feminist awareness of gender’s role in these conventions). Before, as a unicorn, she could move about in the story relatively freely, acting at once as a figure drawn from centuries of unicorn lore and as one idiosyncratically cast as the guiding light of Beagle’s metafantasy. Now, she is unicorn-Amalthea, browbeaten by Lír’s insistence on the genre to which their story belongs, but she remains steadfast against the will of her genre’d body and resists its narrative conventions, if perhaps because she is ignorant of them.

That is, unicorn-Amalthea remains unchanged until she is chastised by, of all people, Molly: “You are cruel to him.” To which unicorn-Amalthea retorts: “How can I be cruel? That is for mortals. […] So is kindness.” Unicorn-Amalthea retains her aloofness from those social and material concerns that make humans human in her eyes, but Molly continues, shyly:

“You might give him a gentle word, at the very least. He has undergone mighty trials for you.”

“But what word shall I speak?” asked the Lady Amalthea. “I have said nothing to him, yet every day he comes to me with more heads, more horns and hides and tails, more enchanted jewels and bewitched weapons. What will he do if I speak?”

Molly said, “He wishes you to think of him. Knights and princes know only one way to be remembered. It’s not his fault. I think he does very well.” […]

“No, he does not want my thoughts,” [Lady Amalthea] said softly. “He wants me, as much as the Red Bull did, and with no more understanding. But he frightens me even more than the Red Bull, because he has a kind heart. No, I will never speak a promising word to him.” (155–156)

And, shortly after, when unicorn-Amalthea expresses her frustration with Schmendrick for making her human, rather than letting her die or be taken by the Red Bull, she continues:

“Now I am two—myself, and this other that you call ‘my lady.’ For she is here as truly as I am now, though once she was only a veil over me. She walks in the castle, she sleeps, she dresses herself, she takes her meals, and she thinks her own thoughts. If she has no power to heal, or to quiet, still she has another magic. Men speak to her, saying ‘Lady Amalthea,’ and she answers them, or she does not answer. The king is always watching her out of his pale eyes, wondering what she is, and the king’s son wounds himself with loving her and wonders who she is. And every day she searches the sea and the sky, the castle and the courtyard, for something she cannot always remember. What is it, what is it that she is seeking in this strange place? She knew a moment ago, but she has forgotten.”

She turned to face Molly Grue, and her eyes were not the unicorn’s eyes. They were lovely still, but in a way that had a name, as a human woman is beautiful. Their depth could be sounded and learned, and their degree of darkness was quite describable. (157)

Though unicorn-Amalthea briefly regains herself when Molly reminds her that the unicorns are the object of her quest, when next we see Amalthea again she is no longer unicorn-Amalthea, but fully the Lady Amalthea, having forgotten her unicornness and her own quest, and its trials, as merely a bad dream to be recounted fearfully to Lír, who delights in at least being spoken to by the lady. Molly is, of course, not entirely to blame for this change, or, rather, for this shift in genre identification for the dual figure of the unicorn/Lady Amalthea, since the scene evinces that some of this change is already taking place. But Molly’s admonition that unicorn-Amalthea treat Lír kindly, that she perform just a bit in the manner of the chivalric romance, comes at a pivotal moment in the narrative, for this is the only glimpse we get at unicorn-Amalthea’s turmoiled mental state, her split identity. Unicorn-Amalthea acts as a canny reader of the genre into which she’s being pulled, noting both its gendered dimensions—that is, her objectification as the object of a quest akin to that pursued tirelessly by the Red Bull, tool of Haggard’s greed and desire—but also the symbolic power of the feminine in the idealized world of romance, the “magic” of being a lady in a courtly world. Lady Amalthea, however, is wholly in thrall to the genre, and falls deeply in love with Lír.

Most of the action between this point and the novel’s second confrontation with the Red Bull, and Lady Amalthea’s transformation back into the unicorn, centers on Schmendrick and Molly, who continue the quest for the unicorns despite the unicorn having disappeared almost entirely behind the human veil of Lady Amalthea. But a crucial moment of confrontation between King Haggard and Lady Amalthea neatly centers the plight of the latter in the genre to which she is now beholden and also reveals the genre of the fantasy romance as a powerful, powerfully human, and deeply important structure of feeling that is not to be discarded easily. It is at this point, when the fantasy of the chivalric romance has nearly peaked and tipped into the denouement of a royal wedding, threatening to overtake the novel entirely, that the central quest of the book, with its lofty goal of recovery, seems nearly lost.

The scene occurs when Lady Amalthea has forgotten who/what she was, when all of her attention is focused on her gallant knight Lír, who continues his questing out of habit as much as generic duty. Amalthea, out of similarly new habit as much as generic duty, does what any good lady in a romance does: she watches from a tower as her knight-love returns. Into this moment of pure generic romance looms King Haggard, who corners the Lady Amalthea on the parapet, terrifying her with the accusation that she is a unicorn and revealing his that his Red Bull drove all of the world’s unicorns, except her, into the sea, where they break rhythmically forever on the shore in sight of his castle—an immortal herd harnessed by the bridle of one man’s craven, insatiable desire to possess that which is beyond human knowing. Lady Amalthea protests again and again that Haggard is mad and implores him to act in a courtly manner, to hail the coming of his son triumphantly returned from another quest, lance held high in the sunlight, singing songs of love. When at last Haggard leaves and she is found by Schmendrick atop the parapet, the Lady Amalthea has begun to cry, marking her as nearly too far gone to become unicorn again. She is on the precipice and Schmendrick rushes to bring the final confrontation to a head, lest she disappear entirely into the narrative, into romance, into the human.

The tale of a lady in a tower, often trapped, often by an evil witch (in this case, in a witch-built castle), is a classic of European fairy tales, but it is also a story well known in the Arthurian cycle and perhaps most famous from its many tragic nineteenth-century interpretations in the form of poems and paintings of the Lady of Shalott. Beagle nods to the convention of the lady in the tower and its tragic, Tennysonian resonances, which threaten to fully overtake the unicorn and drown her in the sea of humanity. Amalthea is as much a maiden trapped in a tower as she is a unicorn trapped in human form as she is both of them trapped in a genre not of her choosing. But Haggard proves, as with his adoption of Lír, the agent of his own demise, for in disrupting this moment of romance, of the noble lady on the parapet awaiting her knight—a scene so longed for by Lir and now being written gladly into the story by the Lady Amalthea—, Haggard pushes Amalthea into an even more human moment than that of the romance, into a confusion of memory and being, bringing her to tears and hastening Schmendrick’s search for the unicorns.

But it is Lír himself, to whom the gravity of the romance narrative pulls so strongly, who makes the fateful choice to transcend the genre’s tropes, to return the novel to the unicorn and her kin-quest. For when Lír, Amalthea, Schmendrick, and Molly at last find the lair of the Red Bull, despair grips Schmendrick and he declaims, “Let it end here then, let the quest end. Is the world any the worse for losing the unicorns, and would it be any better if they were running free again? One good woman more in the world is worth every single unicorn gone. Let it end. Marry the prince and live happily ever after.” To which Lady Amalthea, nearly fully gone from her unicorn-self, responds, “That is my wish.” And it is Lír who says “No” (211).

Lír, who has grown wise in the ways of his genre and his role therein, proclaims that “the true secret of being a hero lies in knowing the order of things”: “Quests may not simply be abandoned; prophecies may not be left to rot like unpicked fruit; unicorns may go unrescued for a long time, but not forever. Happy endings cannot come in the middle of the story. […] Heroes know about order, about happy endings—heroes know that some things are better than others. Carpenters know grains and shingles, and straight lines” (212). Again the idea of hero as a trade, as necessary labor in service of social good, rears its head. Lír acknowledges his own complicity in creating a narrative around the Lady Amalthea, in seeking his own happy ending before ere the unicorn’s quest is complete, and so to do right by his companions’ original quest he forsakes the narrative structure of the chivalric romance, denies his own potential for generic closure, and attends to the needs of Amalthea, whom he now understands is the last unicorn. He plies his trade—as the carpenter, the weaver, the brewer, the hero The Last Unicorn needs him to be, penned so lovingly into this metafantasy by the writer we need Beagle to be.

When at last the climactic confrontation with the Red Bull comes, when Schmendrick restores the unicorn to herself in a moment of true magic, breaking his own curse and restoring her properly to the narrative, Lír still has a final role to play in the metafantasy: “heroes are meant to die for unicorns” (223). His ultimate quest lies not in romancing and marrying the lady into a happily-ever-after but in fulfilling the book’s sacrificial demand, to become a tragic figure and so stir what human love remains in the unicorn, to remind her to live for that memory, and thereby to rally and defeat the Red Bull. And when this is done, when the castle of King Haggard has fallen, when Haggard has succumbed to his world-rending greed, when the prophecy of Hagsgate is fulfilled by the noble sacrifice of a son of their own, and when the unicorns surge from the sea and rush out across the world, restoring Haggard’s dismal, dying land and in turn the world, then the unicorn gives a final gift—the kiss of her horn that revives Lír to new life and sets him a new quest to pursue another kind of recovery: to be a good king.

Beagle’s metafantasy in The Last Unicorn deploys the theme of heroism and the heroic genre of the romance, particularly the “medievalizing” interpretation of the chivalric romance from Walter Scott on, in its critique of the developing genre of modern fantasy. I’ve echoed Miller’s extremely important insight that while Beagle plays mockingly with the hero and the tropes of the genre, he does so with a sincere love for what heroism and romance mean to readers, to literary and cultural history, and as a structure of feeling and literary form that holds incredible weight, philosophical insights, and value for a modern world deemed so lacking in heroes. For this reason and many others to do with Beagle’s unnervingly prophetic mapping of the tropes and themes that will come to dominate genre fantasy from the 1970s onward, The Last Unicorn is a masterpiece not just of the genre, not just as a metafiction, but also as a work of criticism that helps us better theorize fantasy and its power over/for readers.

As Matthew Sangster argues in Fantasy: An Introduction, fantasy is a genre that very often surfaces self-conscious concerns about its own value to readers and to society. It does so especially through narratives that critique characters who cannot tell the difference between fantasy and reality, who lose themselves in the escape offered by the genre. The Last Unicorn is not at all worried about its value and actively plays with the boundary between fantasy and reality, containing such play in a metafantasy story/world that gleefully acknowledges how some might very well find fantasy to be silly and trite, but which knowingly offers up fantasy as a cognitive space for experiencing the “real” world and all its complexities, disappointments, and beauties. Beagle does so at one level by disallowing the complete immersion of Lír and Lady Amalthea into the chivalric romance; at another by disallowing the complete restoration of the unicorn to her old self, for she is forever haunted by a lingering, all-too-human melancholy and the memory of her love for a human—that is, her memory of having been generic; and at still another by disallowing Lír his “happily ever after,” instead saddling him with the responsibility to become a good king, a mantle he wears with the same dignity as the hero’s.

Beagle gives us, in the very end, an extended finale not unlike Tolkien’s final chapters—though nowhere near as long, measuring here at just over twenty pages—during which we travel with Lír and Schmendrick and Molly across Lír’s newly inherited kingdom. Together they survey the rebirth of the land in the wake of the freed unicorns’ escape back into the world and the lifting of the curse from his father’s kingdom. Beagle, through Schmendrick, teaches Lír that his new quest is not to pursue the unicorn, whom as Lady Amalthea he once loved, and so gain another, final glimpse of her, but instead to remain in his kingdom, to govern justly, to rule wisely. This is tale-as-old-as-time stuff, but it is—like heroism, like unicorns—nonetheless important, and it is also a rejection of the impulses of greed and desire that drove Haggard and cursed his land. King Lír’s new quest attends in a wholly different way to the world of chivalry that lurks in the background of stories about kings and knights and their great doings, for those kings must rule somebody and those knights must pay for their quests through the wealth generated by feudal estates somewhere.

For Lír, who has experienced the love of a unicorn, who has been revived by the touch of her horn, who has in some sense gone beyond the bounds of the genre and touched something “real,” this new quest is an almost impossible task. But Lír is a hero. He will ply his trade. Beagle is skeptical, as many in the era of American consensus culture’s demise were, about the value and sincerity of heroes, but in The Last Unicorn he holds out hope for heroism itself—an ideal, a possibility, as beautiful and perhaps as unknowable and unreal as the unicorn, but nonetheless meaningful.

A Good Age for Unicorns?

Heroism and the hero are, of course, not the only critical concern at stake in The Last Unicorn. The novel extends far beyond itself and has sustained decades of discussion. Of particular interest to me, as a cultural historian of fantasy, is how Beagle’s novel fits into its contexts, especially 1960s America—that is, how Beagle responds to his moment, through the novel, and how the moment shapes the novel in turn. My interest in fantasy is both in its literary and philosophical qualities, but also its value as a cultural artifact that mediates America and its ever-changing social, political, and economic histories and discourses. In looking at Ballantine Adult Fantasy more specifically, I am interested in how the canon-making project of the series and the individual novels it (re)published fit into the larger cultural history of the U.S. in the postwar period, and how that history in turn informed the emergence of fantasy and its mass market prominence from the 1970s on. How, then, does The Last Unicorn speak to the Matter of America?

From a purely literary perspective, it has been widely argued that Beagle’s use of metafiction responded to and reflected his literary milieu in the 1960s—indeed, early scholarship on Beagle was as much interested in his contribution to American letters, as a writer of metafiction, as it was in his contribution to fantasy, where his metafiction was considered in early scholarship to be a hindrance to the quality of his fantasy. But scholars like Gary K. Wolfe rehabilitated Beagle within fantasy studies, namely in a 1988 special issue of JFA that put Beagle alongside Harlan Ellison and argued for the importance of Beagle’s metafictional work and its embodiment of the spirit of the 1960s. The beatnik butterfly is the most iconic and obvious “sixties” element of the novel, but there’s little need to rehash that here (see Miller’s exhaustive discussion, pp. 64–70) and in fact I dislike the butterfly very much (though Miller’s analysis has tempered that somewhat).

Beagle spent the 1960s and 1970s documenting American counterculture, the emerging environmental movement, and his bohemian travels across the country. The Last Unicorn drinks deeply of these experiences and transforms them into a critique of America through its narrative. More than that, though, the Americanization of fantasy—that is, Beagle making fantasy not just a play on the European fantastical traditions that informed the genre’s modern development, but something that also spoke keenly to American contexts—is at work from the very beginning, before ever the novel starts, for the book opens with a telling poetic dedication:

To the memory of Dr. Olfert Dapper, who saw a

wild unicorn in the Maine woods in 1673,

and for Robert Nathan, who has seen

one or two in Los Angeles

Beagle locates the novel, and the fantastical creature at its center, within an American frame with his dedication of the book to the Dutch cartographer and author Olfert Dapper, who allows Beagle to place unicorns not in medieval European woodlands, but in Maine’s in the era of European colonization. Of course, Dapper never saw a unicorn in Maine—not because they didn’t and don’t exist, but because he never left the Netherlands in his own lifetime. In fact, he didn’t even write the book that described unicorns living in Maine. It was Arnoldus Montanus who did: a 1671 book titled De Nieuwe en Onbekende Weereld [The New and Unknown World], which was misattributed to Dapper in a 1673 translation into German. Montanus doesn’t claim to have seen a unicorn himself, but merely reports that there are unicorns in the Province of Maine near the border with New France, as given in the 1671 English translation by John Ogilby:

there is seen sometimes a kind of Beast which hath some resemblance with a Horse, having cloven Feet, shaggy Mayn, one Horn just on their Forehead, a Tail like that of a wild Hog, black Eyes, and a Deers Neck: it feeds in the nearest Wildernesses: the Males never come amongst the Females except at the time when they Couple, after which they grow so ravenous, that they not onely devour other Beasts, but also one another.

The book also included an engraving that placed the creature—not named explicitly as a unicorn, just “a kind of Beast”—alongside an American menagerie, including a moose or elk, a very fierce beaver, and a giant rat (a nutria?), with palm trees in the background.

Beagle’s dedication, its misattribution, and the original text’s wild story of chimeric unicorns roaming the woods of North America anchor the novel firmly in an American genealogy of the fantastic that seems an appropriate admixture of the real and the imagined. This Maine unicorn’s origin lies in early colonial efforts to “know” the world, spoken of at far remove by pre-modern knowledge-makers who thought of unicorns and dragons as living alongside beavers and lions, whose vision of the world in comparison to ours looks very much like a thing of fantasy, and which is (mis)(re)presented through layers of interpretation, accounting, translation, and misunderstanding. It’s a fascinating moment of intended and unintended meaning that wonderfully and whimsically places the novel. Beagle’s simultaneous dedication of the novel to his mentor, novelist Robert Nathan, and the unicorns he’s seen in LA, further cements the fantasies of The Last Unicorn not in medieval Europe, but in America, sixties California, the urban U.S. (original locus of the novel in the 1962 draft), and the world of the counterculture. The unicorn is a creature caught between times and places—out of time and place—and realer than whatever knowledge seeks to make meaning of her, to keep her in one time or place.

The Last Unicorn plays with the artful evocation and purposeful rearticulation of the medieval, of folk- and fairy tales, for a new generation burdened by the injustices of the past at work in the present and thus rightly skeptical of the future. It is a “medievalizing” fiction, as Miller puts it: a process of association and play with the medieval, rather than a destination, a finality, an attempt at recreation (like a secondary world), or mere evocation (like Le Guin’s Poughkeepsie fantasies). As the popularity of Tolkien in the mid-1960s demonstrated, fantasy could offer postwar readers a powerful critique of modernity. Readers took seriously the idea of reenchantment in Tolkien’s work and fit it to a multitude of ongoing projects—arts and crafts, hippie culture, the folk music revival, Renaissance fairies, neopaganism, the sexual revolution, and so much more—that in the right circumstances were aligned with political interests in Civil Rights, anti-war campaigning, gender equality, or the environment. Reenchantment excited the counterculture and its possibilities vibrated into new frequencies in The Last Unicorn. The novel’s title, they found, was not a funeral dirge but the start of a quest; a challenge, not a death sentence. It offered a faint hope that the crises of this generation didn’t have to be the end, but could be ended, and their injustices repaired.

The Last Unicorn also speaks pointedly and persuasively to people’s disenchantment in/with/of American modernity, as allegorized by the unicorn’s own concern at learning that she is the last; by her quest to restore the unicorns, who are for her the source of meaning in the world; by her experiences of the human world, whether the conman carnival of Mommy Fortuna or the bandits who do little but invent the myth of themselves or the people of Hagsgate who neither delight in their good fortune nor consider its toll on others; and by the Red Bull and King Haggard and their army of representative allusions to greed, desire, envy, patriarchy, capitalism, and more. Beagle diagnoses this unnamed, Renaissance faire version of America as a world without magic, willing to believe the illusions it is sold, and that has turned its back on the common good. But this world also, importantly, deserves to be reenchanted: both by nature reborn from the vanquished greed of evil and by the perhaps more mundane but no less meaningful rebirth of a social order that is just and fair, represented by Lír’s final quest of rulership.

The novel might be read, in whole, as a sort of allegory for the state of America in the 1960s as a haggard kingdom in thrall to capitalism and greed and the devastating logics of modernity, and which through the figure of the unicorn and her comrades—through fantasy’s imaginative powers, through collective action, through the rejection of the scripts that interpolate us into systems of power—might be recovered. If so, we can think of Beagle as arguing that fantasy has an important role to play in reenchanting the world, and indeed that escape—understood not simply as a retreat from the state of the world but as an embrace of the metafantastic awareness made possible by the novel—might be a valuable political tool. These arguments still ring true now and were especially the case in the increasingly disillusioned world of the 1960s, when so many were both galvanized to political action (and a newfound love of fantasy!) and also stricken by what Beagle calls “The American ailment” in his 1986 novel The Folk of the Air (see Miller, pp. 38–39): despair and depression and the monotonous meaninglessness of life. These affects abound in The Last Unicorn.

Perhaps the best evocation of this is in the scene described above, when Schmendrick nearly gives in to the narrative impulses of genre, thinking to abandon the unicorn to her generic life as Lady Amalthea. Were he to do so, his own curse would remain intact, and he would forever be a youth, endlessly striving for true magic, endlessly playing the fool for Haggard. But while Beagle’s novel is hopeful, and while it does ultimately call for the reenchantment of the world, Beagle is smart to temper that hope with the experience that the permanent youth of ignorance lacks. This American ailment, personified best in the Red Bull, is never fully defeated, only driven into the sea, and remains in the hearts of all touched by it, who hold dear everything lost and gained in the quest for the recovery of the world, and keep a melancholy reminder of the possibility for disenchantment even in the best of times.

The inciting moment for the novel’s quest comes when two hunters enter the unicorn’s timeless lilac woods. The elder of the two, wiser in the ways of the world and learned in the folk knowledge of unicorns and their ancient magic, bids them leave these woods: they will catch no game here. His medieval age of longbows and hunts by horseback is too modern by many centuries to be a world where unicorns still dwell, save this last one. As they depart, the younger man asks the elder, “ Why did they go away, do you think? If there ever were such things?” To which the elder replies, “Who knows? Times change. Would you call this age a good one for unicorns?” (4). The younger answers no. Perhaps no age is good for unicorns, no age deserving of the beauty of nature and enchantment and good that becomes of having unicorns in the world, and certainly not ours—and the younger hunter says as much when he surmises that no man in any age would say theirs is a good one for unicorns. Finally, as the hunters leave the woods, the loreful elder calls out to the last unicorn, whom he knows with such certainty lives in these woods without ever having seen her: “Stay where you are, poor beast. This is no world for you.”

The unicorn, as we know, does not stay in the woods. The unicorn does not care whether this age is a good one for unicorns, nor whether this is a world for her at all. For the world is hers, regardless, it is the world of nature and beauty and good, as much as of death and ugliness and evil. The unicorn does not care about the way of things, about the structures of power men have walled themselves in with, or about the narratives and genres they have woven around what is appropriate for the world and not, what belongs to it and not, and to whom it belongs or not. She cares for her kin and for what their absence—and their recovered presence—means for the world. She is willing to risk her immortality for it.

Against the unicorn’s willingness to sacrifice herself for the world are contrasted the villagers of Hagsgate. They, like so many living in the postwar period and afflicted by “The American ailment,” are thoroughly disillusioned with the promises of their lives. The witch-curse placed on King Haggard’s land means that only Hagsgate will reap bounty from its crops and grow rich, while all the kingdom starves and lives meager, oppressed lives until the prophecy of Haggard’s doom by a child from the village is fulfilled. The people of Hagsgate are unwilling to celebrate their bounty for fear of its loss, keenly aware of the awful price extracted for their bounty from the rest of the kingdom, and viciously defensive of any challenge to their way of life, murdering all the children born there save one, Lír. Hagsgate offers a powerful allegory for the state of America and the postwar generations living on a bounty reaped in a world of sorrow and devastation, of global schemes to lift up the developing world while profiting from new extremes of extraction and exploitation, and in a nation fearfully protective of the fruits of such injustice and willing to claim lives, at home and abroad, to maintain the status quo.

Unlike the unicorn, the people of Hagsgate are unwilling to risk anything. When the curse on Haggard’s land is broken, their fields wither, their wealth wallows, and their homes crumble to ruins. Fifty years of exploitation come home to roost, while fifty years of natural bounty denied the rest of Haggard’s kingdom bloom at once in the grandest spring imaginable when the world’s unicorns are freed from the sea. Surveying his lands in the final chapter, Lír chastises the people of Hagsgate:

“Wretched, silly people, the unicorns have returned—the unicorns, that you saw the Red Bull hunting, and pretended not to see. It was they who brought the castle down, and the town as well. But it is your greed and your fear that have destroyed you.”

The townsfolk sighed in resignation, but a middle-aged woman stepped forward and said with some spirit, “It all seems a bit unfair, my lord, begging your pardon. What could we have done to save the unicorns? We were afraid of the Red Bull. What could we have done?”

“One word might have been enough,” King Lír replied. “You’ll never know now.” (237)

Beagle harshly and justly lampoons the will to inaction when change seems impossible, or at least very hard, or perhaps just sort of scary. He also clarifies that looking away is a choice: pretending not to see the evils of the world as they play out is a choice just as much as knowing and never saying a word. Beagle’s novel offers a clarion call in the midst of an anxious generation searching for meaning, learning to fight back against a multitude of injustices, and trying to understand its place in the postwar world of American empire. His is the simple but eternally important, ever hopeful reminder to try. “One word might have been enough.”

Any age is a good age for unicorns.

Postlude: The Sound of a Spider Weeping

I want to end with my favorite moment in a novel that strains its bindings with many such extraordinary, beautiful, and critically weighty moments. It is a melancholy moment, but it is deeply affecting and easily forgotten, for it is but two paragraphs in a busy chapter.

When the unicorn is captured and put on display in Mommy Fortuna’s Midnight Carnival, we are treated to a tour of its illusory menagerie. But aside from the harpy Celaeno, there is one among the pitiful creatures who is not like the others. The spider Arachne, described by Mommy Fortuna’s majordomo Rukh as the being from Greek myth who “had the bad luck to defeat the goddess Athena in a weaving contest,” and so was transformed into a spider, forever weaving “[w]arp of snow and woof of flame, and never any two the same” (24, 25). But this illusion is of a different sort, for it is nearly real, or as near to real as illusion can be, because as Schmendrick says “the spider believes. She sees those cat’s-cradles herself and thinks them her own work” (25). In so fooling herself, she has become something more than a spider. But should others stop believing in the illusion, should the illusion fail entirely and she not see her wondrous imagination reflected back at her in the simple webs she really weaves, “there’d be nothing left […] but the sound of a spider weeping. And no one would hear it” (25).

It is a deeply sad scene and a beautiful one. It speaks, I think, to the role of the artist in a world that craves entertainment and art and illusion, to how the artist sees themself in their work, most especially when the value they see in their art is shared and expounded upon by their audience. It speaks to the loneliness and heartbreak of not being able to create the art you want to, whether from lack of skill or circumstance. It speaks to stepping back from something that at first seems like a great work, and discovering it’s shit, and thinking maybe you are too. It speaks also to fantasy and its power over us, and, I think, to the complicated ideas about genre and metafiction and structural power discussed throughout this essay. And it speaks to the novel’s enduring themes of seeming versus/and/or being, and to the act of creation as fundamentally powerful—magical, even.

It’s a small moment, and easily forgettable in this short novel sprawling with brilliance. But I don’t want to forget that spider. And I hope, should she ever weep, that I would have the ears to hear.

To get notifications about new essays like this one sent directly to your inbox, consider subscribing to Genre Fantasies for free:

Round of applause and looking forward to reading the whole blog on the strength of this.

And I love that book by Williamson too, and really appreciate the way you’ve set this against American history (honestly I think a history of fantasy as an American genre would be fascinating – I think Colin Manlove’s book on English fantasy did something of the sort for England, but I don’t know of anything for this other heavier side of the pendulum).

I didn’t like The Last Unicorn when I read it. The mockery of the genre came across a lot stronger than the love of the genre for me. Reading this and Goldwag’s take on it has tempered that a lot and I’m going to give it a second try, but I’m still not sure whether I’ll like it. I suspect I’m going to find its messaging muddled due to the way it often views its characters as archetypes – as an example, is it fair for Lir to blame the townspeople for not speaking up when by the story’s logic, they were just playing their role too?

But this review at least gives it a shot now!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m not sure I would have liked The Last Unicorn if I’d read it even five years ago. Not to say this is the kind of book you have to grow into, and I might not have liked it in a different week or month even last year, so I totally get someone not enjoying this. I certainly did not enjoy Beagle’s first novel, which I get to a bit later in this series. Like, I didn’t enjoy it at all (which irked some folks!).

And thanks for your kind words about my approach. Yes, my goal is basically to spend the rest of my life producing this kind of cultural history approach to fantasy (and sf) and, eventually, writing a bigger project that synthesizes it all into a cultural history of fantasy in the 1970s-1990s. We’ll see if I ever accomplish those goals!