Land of Precious Snow by Thaddeus Tuleja. 1977. Avon, 1980.

Table of Contents

Who Is Thaddeus Tuleja?

Reading Land of Precious Snow

Seventies America, Rampaism, and Land of Precious Snow

Thaddeus Tuleja’s Land of Precious Snow tricked me.

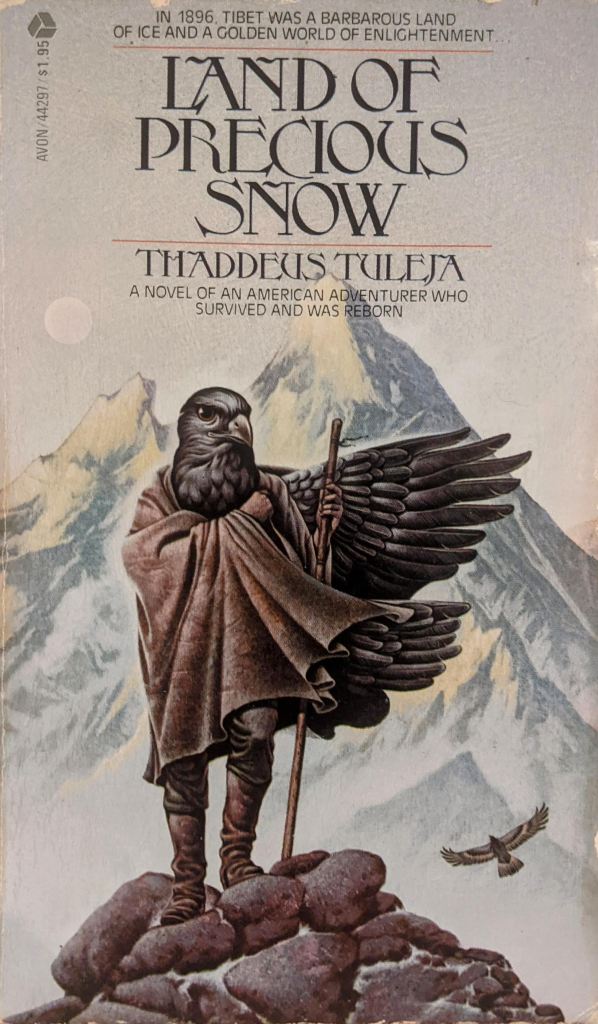

This is a novel that (almost) no one has talked about in the field or in public criticism, that doesn’t produce references in any critical database for literary or sff studies, and whose author is something of a mystery. I found it shelved in the sff section of one of my favorite used bookstores in Syracuse. The cover art has a promisingly fantasy appeal, with an imposing birdman adventurer leaning on a staff atop a mountain, even higher mountains of the Himalayas looming up behind him, a vulture soaring in the distance.[1] The novel was originally published by Python in 1977 and republished, with the same cover, by Avon in 1980. Avon was known in the early postwar period for their romance novels and comics, but by 1980 they were also publishing a good deal of fantasy, science fiction, and horror—usually more off-beat, eclectic stuff. So you can perhaps understand my confusion. And if these details don’t convince you, the cover copy suggests the mystical and fantastical:

Land of Precious Snow evokes a world of ice and demons, hermits and magic; traces a journey from the terrifying hallucinations of death to the majestic monasteries of eternal wisdom; and brings to life a land, wind-carved and cedar-scented, where the only truth is: as you imagine life, so it is…

And yet, Land of Precious Snow is not a fantasy novel.

It is mystical, in the sense that it deals with a character’s religious and/or spiritual experiences, which are in some sense fantastical or at the very least edge toward the fantastic along a “realist horizon” (I’m indebted here to a recent article by Tim Murphy for this conception and phrasing). At the same time, the novel is framed in the tradition of occult and New Age books that seek to explore the mystical east, particularly Tibet, for the purpose of Westerners’ spiritual and personal growth. But Land of Precious Snow is, essentially, a work of historical fiction about religious experience—the author, in our correspondence, has called it a “spiritual adventure”—and not a work of genre fantasy, though it is nonetheless interesting as a provocative edge case for scholars of fantasy, since the novel’s framing to its audience, and its narrative about religious experiences that certainly seem fantastical, raises questions about the fraught boundaries between realism, fantasy, mysticism, spirituality, and religion.

Who Is Thaddeus Tuleja?

This mysterious and provocative novel was written by Thaddeus Tuleja. ISFDB records Land of Precious Snow as its author’s only standalone novel, and lists Tuleja as the author of seven other novels, under the pseudonym Marshall Macao, in a series called K’ing Kung-Fu—a series of martial arts novels that took part in a cultural moment of serious interest in Chinese martial arts.[2] Simple searches for Tuleja turn up several names, including Thaddeus V. Tuleja, Thaddeus V. Francis Tuleja, and one Tad Tuleja. Tracking down these names reveals that Thaddeus V. Tuleja was a WWII U.S. Navy officer and later historian of eastern Europe. ISFDB’s data on Tuleja came from Robert Reginald’s massive 1992 bibliography, Science Fiction and Fantasy Literature, 1975-1991, and clarified both the author’s identity as Thaddeus V. Francis Tuleja and his birth year in 1944 (so, likely the son of the historian). With this data, I was able to guess that middle-name-Francis and Tad Tuleja might be the same person, based on some obscure hints online that Tad Tuleja was born in 1944. I reached out to him and was able to confirm all of this.

Tad Tuleja is a really interesting guy. A recent bio given for a presentation at a 2021 conference reads:

A folklorist with particular interests in ethnicity, stereotyping, conspiracy theories, and popular culture. Tuleja was educated at Yale, the University of Sussex, and the University of Texas at Austin, where his doctoral dissertation examined the mass media “othering” of Mexico in the 1920s. [… H]e has presented on subjects ranging from calendar customs and slang to competing “memory narratives” of traumatic events. As a songwriter, he received a development grant from the Puffin Foundation and has just released a debut EP entitled Waters Wide Between. At Harvard, Princeton, Colby College, and the University of Oklahoma, Tuleja taught courses on ethnicity, gender, revenge, urban legends, and military culture and has authored several scholarly articles and thirty books.

A prolific man, indeed, Tuleja worked as an editor in the 1970s with Venus Freeway Press, where he oversaw the K’ing Kung-Fu series and wrote three (not seven) of those books. He became interested in Tibetan Buddhism and wrote Land of Precious Snow to invoke a world where those spiritual interests could be pursued, through literary adventure in the vein of, say, H. Rider Haggard or Talbot Mundy, to Tibet itself. Tuleja also wrote an unpublished sequel, Guardian of the Snow, and had plans for a tetralogy that never saw the light of day.

In 1997, twenty years after publishing Land of Precious Snow with Python, Tuleja received a PhD in folklore from the University of Texas, Austin. In the preface to his dissertation—Looking South: Framing Mexico in the Tribal Twenties, a study of cultural processes of othering Mexico in the U.S. mass media—Tuleja refers to the UT Austin program as his third go at graduate school, and one for which he put his writing career on hold. During the previous two decades, Tuleja wrote multiple nonfiction books across a range of topics, especially short-entry reference works about history and culture. From 1997 onward, his work was mostly academic publications in folklore studies and American cultural studies. More recently, Tuleja has also released two short (and I think reasonably good) folk albums, Waters Wide Between (2019) and Gather (2022), under the artist name Skip Yarrow. Both are available on Spotify and I highly recommend “The Watcher.” That song and Tuleja’s pseudonymous surname were inspired, respectively, by a scene and a character from Ursula K. Le Guin’s A Wizard of Earthsea.

Reading Land of Precious Snow

Tuleja’s Land of Precious Snow is set between November 1896 and September 1897. Most of the relevant background context for the novel is given in the back cover copy:

He was raised by wild Indians, Chinamen, and Parisians—but all Jed Day knew of his heritage was that it was as exotic and mysterious as the fabulous jewels his father parlayed into a fortune along New York’s Millionaire’s Row.

Then all of his past was slashed into oblivion high on a Himalayan glacier by the sword of a black-toothed bandit, who slaughtered his father, ended a great quest for the rarest of earthly gold—and began for Jed a greater quest, for an even more wondrous possession.

Well, this background context is sort of relevant: Jethro “Jed” Dey is the main character but the description of him being raised by “wild Indians, Chinamen, and Parisians” is nonsensical, combining disparate elements from his grandfather’s and father’s lives, not his. His father also hadn’t parlayed any fabulous jewels into the family fortune; it was his Canadian “mountain man” grandfather’s finds in various unspecified gold fields that bought that fortune. Jed’s father John Pierre was in fact a rather normal, if liberal, man whose nouveau riche fortunes were further enhanced by his fashionable marriage to a Bostonian society lady and his boutique import firm for art, jewelry, and artifacts from Asia—supplied to the richest business tycoons of America’s Gilded Age.

This back cover copy confusion is appropriately relevant to Land of Precious Snow and the critiques it levels at American society and capitalism through the lens of historical fiction. To the Gilded Age elites of the day, who trade in American chauvinism and feed off the fat of capital and empire, the Dey family is an exotic outlier: new money, odd backgrounds associated with Indigenous people and East Asians, using on-the-ground knowledge that transgresses imperial boundaries to make themselves richer and slake the extravagant, Orientalist thirst of respectable, normal, boring, and bored titans of industry.

To that end, Tuleja’s novel opens not with Jed Day, tantalizingly left to die on a Himalayan glacier, but many months after Jed’s ordeal on the mountains, with a sputtering, enraged lawyer for the Sugar Trust, William Detroit, railing to himself against his boss, betraying the racist and elitist views the narrative will challenge throughout:

King Cane’s fault, all of it.

Had the sugar tycoon been content to decorate his mansion with good American workmanship instead of a sybarite’s hoard of Oriental baubles, John Pierre might never have been brought into his orbit, Jennifer would never have met his bohemian son [Jed], and there would be no talk of an expedition. (11)

The opening chapter takes place in February 1897, several months since the last communication from John Pierre and Jed Dey, who have gone on expedition—first to India, then to Nepal and finally, when that failed, toward Tibet—in search of rare “white gold” jewelry coveted by one of the leading sugar barons. Because no word has been heard from them, the media has declared them missing and William’s son, Will, has been making claims—to his father’s dismay—that the Detroit family will fund an expedition to find them. Jed is a dear friend to Will and many suspect that Jed will marry Detroit’s daughter, Jenny. Of course, Detroit has no interest in funding such an expedition nor in Jed as a son-in-law, but once it’s in the papers he can’t very well say no.

It might seem like an odd start to the novel, especially since we never see William Detroit again after the first chapter, and it is at first a tonal mismatch with the rest of the book’s focus on the stark, harsh Tibetan landscape and the spiritual cleansing it allows Jed under the tutelage of a hermit named Naldjorpa and later the Chagpori monks. It might seem all the stranger because most of the chapter’s twenty-two pages are taken up with lengthy descriptions of Gilded Age high society, described from the perspective of Detroit and his many concerns: about bomb-throwing anarchists, about the legal troubles faced by the Sugar Trust over their monopoly of the trade, about the coming war with Spain over Cuba and whether such a war will benefit American corporations, about the necessity of strike-breaking and a strong anti-labor government, about the social deterioration caused by “progressive” elements in society, about overly liberal educators at Harvard who teach things like the Bhagavad Gita and Transcendentalist writing,[3] and about much, much more. Detroit reads like the kind of figure Mark Twain might have lampooned in the latter decades of his career. The chapter establishes the concerns and ideologies and vices of a world that is the very antithesis of the land of precious snow, of Tibet—a world that can offer Jed, and perhaps us, respite and release from modernity, a world free from the mindless, meaningless toil of capitalism, ever in service of a greater search for meaning beyond the world’s illusions.

With the second chapter, Land of Precious Snow takes us back in time several months to November 1896, where we find Jed Dey the lone survivor of a bandit attack on his father’s expedition. The descriptions of the attack are quite brutal, but they come to us in drips and drops: Jed is out of his senses, freezing to death on a glacier, suffering from shocks, and meandering in and out of consciousness. This chapter and the fourth (three is a brief interruption that sees Will in Paris at the start of his own expedition to find Jed) are narrated in a disorienting, almost stream of consciousness style that attempts to mimic Jed’s sense of displacement and confusion, as he experiences pain, maybe death, maybe demons, maybe prophecies, and relives the bandit attack again and again in increasingly more fantastical ways. It is stylistically interesting, but a bit repetitive to read, though by the end of this section, it seems clear that Jed has experienced something near to what we might interpret as Buddhist Enlightenment, or perhaps what is really an experience of near-death euphoria interpreted by his spiritually-inclined self as Enlightenment:

Still he was now, beyond feel. It was a sensation unique in his experience, this state on the other side of control. His mind at last free of doubt, his body no longer his own, he grinned.

An absorbing, lifting lightness took him. He had the impression he was in and out of his body at once. For a moment he saw himself a stone standard, warning errant travellers, and at the same time the planter of that standard, hovering timeless above the wastes and his own empty carcass, chuckling softly as the stone image was reduced by degrees, by weather and scavengers, to dust.

It was beyond him now. No more than nostalgic fondness linked him to Jethro Dey. He was not of the world of men; he was rolling down, calm and stolid; rolling, centuries long, through a million springs to come. He had become the earth. Thought was not. No dreamer and no dream, but only the land, even in pulse.

The stone figure was still. The border had been reached. Now: dawn.

From the pit of his being light began. It swelled through the sinking frame, punched open the eyes. On a horizon immeasurable to men a blue and blinding sea began its ascent. A hundred generations yet unborn, as many ages gone, had contrived to create that sun. The motion of the planet stopped.

Behind him the sun came up brilliant, casting the shadow of the cross over him and illuminating the three carcasses [of the expedition’s sherpas], already being harassed by birds, that he had been unable to bury. He was facing West, then. Before him the sun caught first the ragged crest of Daulagiri, turning the snow there into a dazzling triangle.

Fire on the mountain. The gold.

And once again he could see.

As he had been the stone, now he was the light. In the deep unfrozen caverns of his being, the image delighted him. He fixed his eye on the mountain and waited to die. (47–48)

Interestingly, Tuleja ties this sense of Enlightenment—of transcending the illusions of life and the boundary of death (described and hinted at throughout this section of the novel)—to the material world of the Himalayas, with the mountain Dhaulagiri, whose name comes from Sanskrit dhawala giri or “(pure) white mountain.” This mountain doesn’t seem to have special significance compared to, say, Annapurna or Kangchenjunga or Qomolangma, other behemoths of the Himalayas, but it is notable that the mountain (which shines in the dawn like the “white gold” of the jewelry his father sought) becomes for Jed almost the mantra around which he mentally and spiritually anchors his willing slide into enlightened nothingness—or death. It becomes a personal, spiritual metaphor for the transformation he undergoes that leads him by the end of chapter four to reject the West, modernity, capitalism, and the religion of his forefathers, a choice he must make a second time, for sure, when Will eventually finds him in a Tibetan monastery and pleads for him to return to America.

Eventually, Jed is rescued by a travelling hermit, Naldjorpa. This is both a name and a title; a naldjorpa in Tibetan Buddhism is a yogic ascetic, sometimes considered to have magical powers, who has attained serenity through careful meditation. He at first experiences Naldjorpa as a god descending from Dhaulagiri—perhaps a manifestation of the mountain itself—but Naldjorpa is a bit of a trickster and refused to ever answer any question directly, instead turning all questions on Jed (the sort of thing someone might imagine is what constitutes Buddhist philosophical inquiry). He does however clarify that he is neither Hindu nor Buddhist, he simply is. (This actually does sound like what many śramana movements taught in their reactions against the hierarchies of Vedism in the 6th–5th centuries BCE; early Buddhism was itself such a movement.) Naldjorpa helps Jed to heal and regularly chastises Jed for the few remaining “Western” preoccupations he has, e.g. around time, “doing,” responsibility, duty; we can question whether these are “Western” but the novel leans hard into framing Naldjorpa’s ideas as the antithesis of what William and Will Detroit believe in. Jed decides to make himself Naldjorpa’s pupil and Naldjorpa sends him to gain a basic knowledge of Tibetan Buddhism at the Chagpori monastery in Lhasa. Chagpori, importantly, is known for its special attention to Tibetan Buddhist healing practices.

After several months, Jed is found by Will. Before this point, we get two chapters (three, seven) about Will’s efforts to find Jed. These mostly serve to detail Will’s severe distaste for Asia and its poverty, and his sincere belief that he can fix the “mess” of “Asia in 1897” by returning home and organizing some charities to send money (158). When Will meets Jed, clad in saffron monk’s robes (though, notably, those are only worn by fully ordained monks), he thinks his friend has gone crazy or let the progressive, youthful ideas taught at Harvard (echoing his father’s fears) get the better of him: “A lifetime among a people infested with lice, a people whose very existence refuted Progress—no, that was too much!” (156). Will presses Jed to return home. But Jed refuses. He “considered himself now, however prematurely, a Tibetan” (150) and knows he cannot get answers to life’s deep, abiding questions back home. He tells Will:

“I am not the person you knew. My father is not the only one who has died. I have died too. This is not a game, Will. I don’t understand what has happened to me, God knows I don’t; but I’ll be damned if I’ll go back to New York without giving it a good try to find out. I have not told you much about the killing [of my father]. I have not told you about what came after [the visions, the near-Enlightenment(?)]. What happened then means I cannot go back, not now, maybe not ever. I came […] that close to being dead myself. I swear to you, sometimes I don’t know whether I made it through or not.” (167)

When reminded of his fortune back home, Jed gives it to Will to use as he sees fit (perhaps to fund one of those charities Will wants to use to help South ?Asia’s poor). Will is sent away and Jed returns to the sangha.

Land of Precious Snow ends later that night with Jed being led to a vast treasure trove deep below Chagpori monastery, hidden in the caverns: an immeasurable wealth of that “white gold”—in jewelry set with precious jewels—that brought him and his father to Tibet in the first place: “He had been given it […] only because he had no longer desired it” (174). Naldjorpa materializes beside him and speaks softly, prophetically: “You are ready […] to begin” (175).

It is, to be fair, the kind of cliche ending we might expect, one that in its very simplicity and its oxymoronic presentation of the treasure to one who no longer seeks it, is meant to be read and understood as deep. But it is nonetheless a narratively effective ending to a novel that is usefully, sincerely, and sharply critical—over its 175 pages—of American ideas about modernity, capitalism, and colonialism in the name of “Progress.” Jed is in search of personal meaning, a pseudo-outcast of his own upbringing, who, because of his parents’ slightly liberal social leanings and his education in “Eastern” ideas at Harvard, finds himself in crisis about his place in the world—over what the world even is, what is real and what is not (philosophical questions Will dismisses as “all right for college, but we’re men now, we’ve got responsibilities, things to do” [168]). The narrative offers, in the end, an entirely personal solution to a vast set of social and structural problems—which, interestingly, Will seems to grasp much better than Jed, but which both of them abrogate the responsibility to actually address, eschewing radical political change in favor of, respectively, setting up a charity and meditating in the mountains. (One wonders how the planned tetralogy would have panned out in this regard!)

Of course, novels aren’t required to imagine solutions to the social and political problems they outline; the value is often in the mapping itself. Land of Precious Snow offers a smart and timely rebuttal to the capitalist spirit of the 1970s. Tuleja’s Gilded Age America, explored in great detail in the opening pages, is little different from the America wrought by Nixon, Ford, and later Reagan. Here and there are the conservative railings against liberal education, the abiding belief that progressive ideas are fracturing American society, and the unfettered capitalist growth attained through industry, monopoly, law, and (neo)colonial expansionism at the expense of workers—who, in both periods, responded through organizing (and some bomb-throwing).

What’s more, Tuleja mixes the critique of America with the then-contemporary interest in “Eastern” philosophies and religions, seeing in Tibetan Buddhism—problematically or not—a potential solution to the materialist hypocrisy of the emerging neoliberal era. In this light, we might read Tuleja as saying that history repeats itself (recall the reference to Santayana; see [3]) but also as referring to cyclical ideas of time (often attributed to Hinduism and Buddhism): this, too, has already happened and will happen again. But more than anything, the clear comparison between the Gilded Age and Tuleja’s 1970s—both periods that, responding to similar social and economic forces, saw a growing interest in “Eastern” ideas as counters to the prevailing, negative forces of their own versions of modernity—reminds us that our historical circumstances are not unprecedented, even if they are unique.

Still, reader, be warned: there are no birdmen!

Seventies America, Rampaism, and Land of Precious Snow

Land of Precious Snow is very clearly about a dissident feeling toward American culture and the West more generally in the 1960s and 1970s that, among many other consequences, led to the rise in popularity of “Eastern” religious practices and New Age spiritualisms in the U.S. It expertly uses the 1890s because that was, also, a time of incredible and ostentatious wealth and poverty, and of U.S. imperial expansion and aggression for both capitalist and nationalist interest—and a period which saw the rise of new syncretic spiritualist practices such as Theosophy and Thelema and neopaganism, as well as the global spread of knowledge about Hinduism and Buddhism, which led to hundreds of Westerners joining Buddhist sanghas in South and Southeast Asia.[4]

Plenty has been written about New Age spiritualism and the appropriation of “Eastern” religions—especially Hinduism, Daoism, and multiple forms of Buddhism—in postwar Europe and the Americas, especially in the U.S. and British countercultures and the many efforts by people of all walks of life in the 1960s and 1970s to “reenchant” modernity. These were part of a larger set of anti-modern or counter-modern practices that, in my view, helped create a fertile ground for fantasy fiction to become a massively popular genre by the end of the 1970s. (But more on that another time!) It’s a rich subject and I don’t want to survey its entire history here, though I will suggest the following as important frameworks for thinking about religion, spirituality, and counterculture during this period: Brown’s The Nirvana Express: How the Search for Enlightenment Went West (2023), Bach’s The American Counterculture: A History of Hippies and Cultural Dissidents (2021), Oliver’s Hinduism and the 1960s: The Rise of a Counter-Culture (2015), McLeod’s The Religious Crisis of the 1960s (2010), and, for a look specifically at these undercurrents in American literature, Garton-Gundling’s Enlightened Individualism: Buddhism and Hinduism in American Literature from the Beats to the Present (2019).

When one considers the increasing historiographical attention to the 1970s as a decade of cultural chaos and political crisis, the search for new and alternative meanings—whether in the forms of spirituality (Tibetan Buddhism, UFO cults, Krishna Consciousness) or literary modes of interpreting and remaking the world (fantasy)—makes a whole lot of sense. Needless to say, the imprint of New Age spiritualism and Euro-American appropriations of “Eastern” traditions are all over popular culture of this period, and no less visible in the genres of science fiction and fantasy, making it easy for anyone then (as now) to associate Land of Precious Snow with fantasy. In fact, Avon published Grania Davis’s Tibetan Buddhist fantasy novel The Rainbow Annals the very same year it republished Tuleja’s Tibetan “spiritual adventure” novel, suggesting that Avon—if not exactly claiming Land of Precious Snow belonged to a specific genre, fantasy or otherwise—was well aware that its readers relished books about Buddhism, about spiritual experiences beyond Christianity, and about worlds and cultures beyond the West.

One particularly relevant intertext with Land of Precious Snow, which I feel is worth belaboring, is the eccentric and problematic oeuvre of books by T. Lobsang Rampa—a Tibetan monk who underwent trepanation to open his Third Eye in order to travel spiritually through the cosmos, who was witness to China’s invasion and occupation of Tibet, who then studied medicine in China, who was taken prisoner and tortured by the Japanese in WWII, who witnessed the bombing of Hiroshima, who escaped to the Soviet Union and did odd jobs throughout postwar Europe and even America until, after some convoluted circumstances involving the NYPD and an African American family, he was able to return to Tibet, where his dying body was transported under the orders of the Dalai Lama to a secret location. Lying catatonic in his mountain catacomb, Rampa’s consciousness was transferred into the body of one Cyril Henry Hoskin, a man in Devon, England, after he fell out of an apple tree and bumped his head. At least, that’s the story told by “T. Lobsang Rampa” (the checks went to Hoskin) in his trilogy of bestselling memoirs: The Third Eye (1956), Doctor from Lhasa (1959), and The Rampa Story (1960).

Put another way, the Englishman Cyril Hoskin perpetuated a literary hoax, one that Tibetanists and Buddhist scholars roundly condemned and revealed the moment The Third Eye was published in 1956. But the book sold 300,000 copies in eighteen months. All the publishers did was make Rampa supply “A Statement by the Author” in (some) future editions, which vociferously defends the claims. “Rampa” wrote 20 books in total, all touching on various esoteric and New Age topics, from Egyptian magic to ufology to treatises on astral projections; one of the books was even dictated to him by his cat, Fifi Greywhiskers, ostensible author of Living with the Lama (1964). Despite his books’ patent ridiculousness, they have sold millions of copies, often reprinted from the 1960s onward in mass market paperback formats with slick, enticing covers that—very much like Land of Precious Snow—purposefully elide the differences between genres: Is it occult, is it fantasy, is it memoir, is it historical fiction? Behind all of these questions, all of these efforts to elude genre classification, even just for a moment, is the question: Is it real?

Donald S. Lopez, Jr. offers a thorough dissection of Rampa’s career, popularity, and relation to actual Tibetan Buddhism in the third chapter of his exhaustive account of Western (mis/ab)uses of Tibetan Buddhism, Prisoners of Shangri-La (Chicago, 1998). He argues that it is Rampa’s “blending” of Anglophone sources on Tibet, “supplemented with an admixture of garden variety spiritualism and Theosophy,” as well as his “discussions of auras, astral travel, prehistoric visits to earth by extraterrestrials, predictions of war, and a belief in the spiritual evolution of humanity,” “that may account in part for the book’s appeal, providing an exotic route through Tibet back to the familiar themes of Victorian and Edwardian spiritualism, in which Tibet often served as a placeholder” (161). Moreover, Rampa’s account, at least in The Third Eye, read—and still does—as convincing to many without prior specialist knowledge of Tibetan Buddhism, with only cultural osmosis as background. Lopez recounts that numerous Tibetologists shyly admit they were inspired by The Third Eye to study Tibet and that his own students, when assigned the book, thought it was the most sensible and realistic account of Tibetan Buddhism encountered in the course so far (until Lopez burst their bubble). Rampa picks up on the general interest many have in Tibetan Buddhism, and uses a smattering of detail and precise authorial rhetoric to create a “realistic” sense of Tibet that feels, to many, “authentic.” This false conception of reality and authenticity, and the purveyance of authority to speak on behalf of Tibetan Buddhism, is what Agehananda Bharati (also quite the “character”!) called “Rampaism.”

I want to be clear that I don’t think Tuleja is in any way making claims of authority to knowledge about Tibet or Tibetan Buddhism in the way Rampa was, though the novel shows that he has clearly read a good deal on the topic, including quite a bit about Hinduism but much more about American history—which makes sense, given that this novel is much more about America in the 1960s–1970s by way of America in the 1890s. (Note: In a later interview after this essay was published, Tuleja told me that Lama Anagarika Govinda’s Foundations of Tibetan Mysticism, available in the West as early as 1969, was a major source of his knowledge.) In many ways, Tuleja is channeling Tibetan Buddhism, and what Tibet signifies to Westerners, in ways similar to Rampa’s contexts: Tibet is a “placeholder” for spiritual growth and the author’s arguments about American modernity. To rephrase Lopez, above, Tuleja offers an exotic route through Tibet back to the familiar themes of the American counterculture.

But Rampa is relevant in other ways. More specifically, The Third Eye, which details the fictional Rampa’s early life in Tibet, his entry into a monastery—Chagpori, in fact—and his initiation into the healing arts practiced there, which include the ability to see auras, to diagnose people’s health issues through that third sight, and more. As noted above, this culminates in Rampa having a hole drilled into his head (trepanation) so that he can use his third eye better, including to travel the cosmos via astral projection. I am convinced Tuleja must have been aware of The Third Eye, if not have read it, since not only is Jed enrolled at the same monastic college as Rampa, but Jed too learns to see auras. Jed also details student life at Chagpori; but where Rampa details exhaustive, torturous exams, Tuleja tells us instead about the canings students receive for answering questions incorrectly or improper behavior.

Many small details are shared, but few of the sensational ones, with one exception: the claim that Tibetans are particularly hardy because, as infants, they are dunked in an icy stream—those who survive are stronger, those who die are spared life’s sufferings. This exact scene is replicated in Land of Precious Snow. It occurs after Naldjorpa has healed Jed and before they reach Lhasa, when they are staying with nomadic herders. The herders are kind and accept Jed, giving their food freely in exchange for his physical labor. It’s the first taste of non-elite life Jed has ever had; non-modernity ain’t so bad. But it’s contrasted with the otherwise hard nature of Tibetan life. The scene of the river-dunking plays out before a confused Jed, who sees the baby die, thinking it senseless and cruel. It’s like the classic scene in any film or novel where a city boy/girl comes to live on the farm and has to kill, say, a chicken. Cruel, yes, but oh so real—realer than whatever happens in cities, than whatever happens in modernity.

I think Tuleja is less indebted to Rampa and The Third Eye than he is riffing on them. After all, by 1977, it was pretty obvious to most people who read beyond The Third Eye that Rampa was a white guy. The second and third books in his initial trilogy—Doctor from Lhasa (1959) and The Rampa Story (1960)—exist purely to explain how a white British man who never traveled to Tibet, didn’t know how to speak Tibetan (he was tested), and didn’t have a Tibetan visa (Scotland Yard asked him) could claim to be a Tibetan monk. Moreover, author statements printed in many copies use all caps claims that the books are TRUE, sort of an indication that there’s a question they might not be. And if that’s not unsettling enough, some later copies even featured Hoskin—clearly a white British man—in Tibetan robes on the front cover. So it’s entirely possible that Tuleja was aware of Rampa’s, let’s say, contested identity. I do wonder, then, if Jed, the white guy who becomes a lama, is a knowing prod at Rampa, despite Tuleja’s intentions with Jed’s story being clearly sincere. And, to be fair to Hoskin, even Lopez is clear that he was sincere, too; the extent to which he actually believed his own story was always unclear and, to complicate matters more, Lopez suggests there is a reading of Hoskin’s narrative within Tibetan Buddhist traditions that makes it plausible from a Tibetan perspective. Whether Jed was a purposeful if multivalent play on Rampa, Jed could also be a representation of one of any number of the Westerners who became ordained Buddhist monks in the 19th and early 20th centuries.[4]

Taking all of these complex strands of relationship to real histories, real and fake lamas, and discourses of (false) authority and authenticity (i.e. “Rampaism”) into consideration, Land of Precious Snow can perhaps be read as questioning the point at which the fantastical, the mystical, and the spiritual tips over into fantasy at a generic level, probing at how much religious experience—which might be read as fantasy to some, regardless of the religion in question, and which is certainly more likely to be read as fantastical in the context of histories of Orientalism, mysticism, Theosophy, etc. and their reification of the otherworldliness of Tibetan Buddhism—has in common with fantasy. I don’t personally, as a critic and historian of fantasy, think that the mere presence of the (potentially) non-realist means that something is fantasy, but the fact is that Land of Precious Snow appears to be playing with this potential reading. We might read Tuleja as casting his audience in the model of the scoffing figure of Will, expecting we’ll interpret anything we don’t understand as fantasy, or perhaps hoping that, in the footsteps of Jed, we will embrace the dissolution of boundaries of meaning.

Still, I wish there had been birdmen. Just one birdman!

To get notifications about new essays like this one sent directly to your inbox, consider subscribing to Genre Fantasies for free:

Footnotes

[1] (Note: For the following to make sense, you’ll need to read the final section of this essay, titled “Seventies America, Rampaism, and Land of Precious Snow.”) The cover art for Land of Precious Snow was painted by Peter Schaumann, who makes for an interesting though likely inadvertent connection, since Schaumann also painted the cover for Carlos Castaneda’s Tales of Power (1974), his fourth (bestselling) book in a series of supposedly ethnographic narratives about the author’s apprenticeship to a Yaqui nagual or shaman or “man of knowledge.” Castaneda, like T. Lobsang Rampa, proved to be a fraud—the key difference being that he didn’t pretend to be the Yaqui nagual himself, but he did somehow get a PhD out of his hoax and his books were bestsellers. Like Tibet, “ancient Native American knowledge” has a particular cache in New Age circles; another one of those “placeholders” Lopez talks about.

[2] The growing interest in kung-fu was part of a larger cultural shift in the U.S. during the 1970s and 1980s that saw a growing interest in all things Chinese (something I have partially documented in the fantasy scene in my essay on M. Lucie Chin’s The Fairy of Ku-She; see the section “Some Productive Themes”). We can attribute some of this newfound interest in China first to Nixon’s opening of diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic in 1972, and later to the newfound global openness of China in the post-Mao thaw following his death in 1976. The 1970s and 1980s reconfigured America’s political and economic relationship with China and led to greater cultural exchange and familiarity, whether in the form of booming American tourism in China in the 1980s or the rise in popularity of Chinese restaurants in the US from the 1970s onward, becoming a staple in every town across America. For many non-Chinese Americans, popular culture became a new way to experience China and make sense of this geopolitical shift, perhaps most popularly in the form of martial arts and especially kung fu television and films, which showcased heroes with near mythic powers—so much so that they encouraged Marvel, DC, and other comics publishers to create kung fu superheroes (see Smith’s Shaolin Brew). Tuleja’s K’ing Kung-Fu series was the prose incarnation of this trend and inspired by the 1972–1975 tv series Kung Fu.

[3] Detroit’s comment is quite specific:

[Jed’s] mother’s profligate social sympathies, the father’s contentious wit, had combined to produce a sensibility both tender and acute—a sensibility, Detroit recriminated, perfectly ripe for plucking by the “progressive” forces who, under the control of Charles Eliot Norton, now ruled Harvard University. The school that had educated presidents was now producing the likes of the N—- radical W.E.B. DuBois [sic.], the Jew[ish] freethinker Santayana, and Jed’s own eccentric tutor, that ranting oddfellow Yarrowville. (26)

Santayana was not Jewish, but Spanish-American, though he was fond of Spinoza and did write the aphorism “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it” (in 1905), which came to be associated most heavily with Holocaust education in the postwar period. Yarrowville, later described as “that anarchist” (27), and referenced regularly by Will and Jed in later chapters, doesn’t appear to be a real person—as far as my research goes—though he may have been inspired by someone; the closest figure I can think is John Henry Wright, a Classicist at Harvard from 1887 to 1908, who met and was influenced by Swami Vivekananda, who toured the U.S. and Europe in the late nineteenth century giving lectures on Hindu religion and philosophy. Though Wright hardly seems an anarchist.

[4] For the contexts that led Westerners to join Buddhist sanghas—that is, to become monks—in the 1880s–1890s, see Alice Turner, Laurence Cox, and Brian Bocking’s The Irish Buddhist: The Forgotten Monk Who Faced Down the British Empire (Oxford UP, 2020), particularly chapter six, “Who Was the First Western Buddhist Monk?” which deftly explains why that’s a somewhat silly question and just how many Euro-Americans were entering sanghas in this period.

3 thoughts on “Reading “Land of Precious Snow” by Thaddeus Tuleja”