Lady of the Bees by Thomas Burnett Swann. Ace Books, 1976. Latium 3. Ace Science Fiction Special 7.

Table of Contents

Recovering Thomas Burnett Swann (1928–1976)

Lady of the Bees at Ace Books

Reading Lady of the Bees

In the Fading World of the Forest Folk

The Inevitability(?) of Rome

I began at the end; I usually do. And so I read first the epilogue of Lady of the Bees: a perfect, haunting, mysterious frame in which to glimpse what lay ahead in this slim novel:

Where is the Bird of Fire? In the tall green flame of the cypress, the lifted flame of the oak, I guess his burning. In the second Troy athwart the Palatine, where Fauns can walk with men, I hear the distant thunder of his wings, woodpecker-swift. Always shadow and sound but not the bird. Always he climbs beyond my capturing, and the wind possesses his cry.

Where is the Bird of Fire? Look up, he burns in the sky, with Saturn and the Golden Age.

I will go to find him. (198, italics in original)

This beautiful prose poem ends the twelfth novel by Thomas Burnett Swann—and the third of five novels he published in 1976 alone! The Bird of Fire is Picus—a god, a king, a lover, a father, depending on who you ask. The Bird of Fire is a very particular bird—the woodpecker (picus in Latin), which fed berries to a baby boy, a twin, named Remus, and which Picus took the form of when cursed by Circe. The Bird of Fire is the young man Remus—now slain, known to his friend, the Faun Sylvan, and his lover, the Dryad Mellonia, as “Woodpecker,” for his spirit, for the birds that fed him in infancy, and for his shock of bright hair against the green of the forests he so loved.

Lady of the Bees is about the tragedy of the founding of Rome, that ancient city which towered over the Classical world and which still looms threateningly large in the Western imagination, invoked by every generation as a warning against their impending Gibbonian fall to whatever barbarian hordes define the times. It is written from the perspective of the mythical, non-human beings—the lofty Dryad and the humble Faun—who suffered as human civilization grew over the mythic centuries between Aeneas’s arrival in Italy and the birth of Romulus’s ill-gotten city. It is a novel deeply entwined with ancient Greco-Roman sources and especially fond of recovering Etruscan history, magic, and ritual to the story. It is a charming, lyrical, and heart-breaking novel by an author who is little remembered today.

Recovering Thomas Burnett Swann (1928–1976)

I first discovered Thomas Burnett Swann about a decade ago, when I purchased a first edition mass market paperback of The Day of the Minotaur (1966)—incidentally, Swann’s first novel—at Curious Book Shop (noted for its impressively large sff collection) across from Michigan State’s campus in the first months of my PhD program. At the time, I was mostly intrigued by the Greek theme and the explicit comparison on the cover to Tolkien. How could this author I had never heard of be so readily compared to Tolkien? Little did I know then, that such a comparison in the late 1960s was particularly timely and was part of the larger moment of fantasy’s emergence, which I’m charting across this Critic / Construct blog but most especially in Ballantine Adult Fantasy: A Reading Series. I did not, however, read the novel and it eventually passed out of my collection.

After reading Lady of the Bees—bought at a different used bookstore, at a very different moment in my life, at a time when all of my energies are focused on the history of genre fantasy in this very period—I have not only reacquired The Day of the Minotaur but also almost every other of Swann’s sixteen novels and two story collections, all published between 1966 and 1977. Because with just this one novel Swann convinced me that his brief, bright explosion of output in the 1960s and 1970s may represent one of the most interesting voices in American fantasy, though he is almost completely forgotten today barring a few websites and recent reviews by fans of “vintage” fantasy fiction.

Given that Swann was only active as a professional sff writer between 1958, the year he published “Winged Victory” in Fantastic Universe, and his death from cancer in 1976, his oeuvre of fifteen short stories, sixteen novels, and two story collections is quite impressive. Five of those novels were published in just the last year of his life, and two posthumously in 1977 (both prequels to earlier novels). At the same time, Swann was a regular contributor to sff fanzines and a regular at sff conventions, was a poet who published independently in non-sff publications (poetry is often incorporated into his stories and novels), and was a professional scholar with a PhD in English literature from University of Florida. He taught for a time at Florida Atlantic University (now a hub of sff scholarship!) before resigning in 1970 due to health issues and to focus full time on writing (his family was relatively wealthy, owning large tracts of land in Florida, including orange groves; his father, also Thomas Burnett Swann, helped revolutionize the midcentury citrus industry in Florida). In addition to his impressive number of novels, Swann also wrote five academic monographs. Two were literary biographies for the Twayne’s English Authors Series, one on Decadence poet Ernest Dowson (1965) and one on Winnie-the-Pooh author A.A. Milne (1971). The others were each a study of a single poet: one on the Pre-Raphaelite poet Christina Rossetti and her “fantastic worlds” (1960); another based on his doctoral dissertation about the modernist poet H.D. (Hilda Doolittle) and her use of classical sources (1962); and the third on Scottish WWI poet Charles Sorley (1965)—incidentally, all three poets are widely considered queer and/or have been productively read through a queer lens, and Dowson was a close personal friend of Oscar Wilde.

If Swann could be said to have a “thing,” as an author, that defined the balance of his oeuvre it was: historical fantasy novels informed by a strong familiarity with a culture’s folklore and mythology, typically that of a civilization historically significant to the ancient Mediterranean world but often older or less well-known than, say, Rome or Greece or Egypt (e.g. the Etruscans, the Minoans, the people of Punt), usually oriented toward the perspectives of non-human characters from mythological races (centaurs, minotaurs, tritons, dryads, minikins—all radically reinvented in his own unique vision), usually centering a major (non-human) woman character who stands in stark contrast to the (human and non-human) men around her, and with a strong thematic emphasis on the violence of human civilization; on nature, magic, and mythic beings as the ideal oppositional forces to humanity’s destructivity; on love, friendship, and sexuality, often with queer undertones and occasional explicit queer relationships; and on poetry and the role of poets in society.

Put one way, Swann’s novels collectively tell a “secret history” of early mythic beings’ struggles against the onslaught of human civilizations, the ultimate destruction of their prehuman world, and the consequent degradation of the environment. Swann ties nearly every novel to a major character, event, or place from ancient (or medieval) history, myth, or literature, usually offering an important spin on “canonical” stories in order to recover what histories, social identities, and ways of relating to one another and to the world were lost by the rise of the “great” civilizations of the West. He imagined that he might be able to tie all of the major taproots cultures of Western civilization together in a grand tapestry of stories about this secret history of the prehumans, expecting that it might take 25 novels or so (Collins, Thomas Burnett Swann, 12). In some ways, Swann’s project is akin to Tolkien’s efforts to recover the “earlier,” mythic ages of Britain, only Swann located his stories at the very beginning of various Mediterranean civilizations’ histories—or, rather, at the end of the histories of the prehuman cultures whose losses are just barely recorded in ancient texts as the “myths” of the past. His novels are a feast for scholars familiar with the ancient and medieval Western canon, given how much historical, cultural, and literary information Swann interpolates to gleefully and critically remix, and also ripe for discussions of gender, sex(uality), ecocriticism, and fantasy’s (ab/mis)uses of history.

Swann’s career and, sadly, life were brief. Not much critical writing has been done on Swann’s comparatively voluminous output; what has been said has been superficial at best and scattered across a handful of short articles and book chapters largely published in the 1980s, usually from publications out of or associated with Florida Atlantic University, and in two master’s theses from that university (in 1981 and 1990). Really, Swann is fresh ground for critical scholarship and there is so much land across his oeuvre to till. I won’t spend too much time here delving into his biography—which is really only covered in any depth in an obscure and insightful thirty-page pamphlet, Thomas Burnett Swann: A Brief Critical Biography, written by Robert A. Collins (founder of IAFA and former FAU professor) and published by the Thomas Burnett Swann Fund at FAU in 1979 (thanks to online used book sellers for always hooking me up!)—but will instead make reference to his biography as it becomes relevant in this and future essays on his novels. I intend to read them all in the next few years with an eye to whether there is a larger recovery project (a comprehensive article or two on one of his major themes? a journal special issue? a monograph?) needed to think through Swann’s incredible, unique, critically rich contribution to fantasy in the 1960s and 1970s. I’m convinced Swann is an author whose work deserves to be reconsidered and which could add much to our understanding of fantasy, its use of (pre/myt)history, and its social and political investments—as he articulated them—in this crucial period.

Let’s begin this tentative project, then, with the remarkable novel that made me fall in love with Swann.

Lady of the Bees at Ace Books

Lady of the Bees was published by Ace Books in 1976. Ace published more than half of Swann’s novels, in large part because of the editorship of Donald Wollheim, who took an instant liking to Swann when he received the manuscript for Day of the Minotaur. After Wollheim left Ace to found DAW Books, Swann continued to publish with Wollheim and five of his novels—including his most controversial, How Are the Mighty Fallen (1974)—came out from DAW. Still, Swann was writing quite a lot in the last years of his life after leaving his professorship to write full time, and he also published books at Ballantine and a post-Wollheim Ace (as well as one book that appeared solely in England from mass market paperback publisher Corgi). Lady of the Bees and Tournament of Thorns—two of his five novels published in 1976—were Swann’s final novels with Ace, since he died in May of that year. Lady of the Bees published the month he died and Tournament of Thorns two months later.

Swann’s last two Ace novels were the seventh and eighth books in the highly regarded Ace Science Fiction Special Series 2 (1975–1977). Lady of the Bees included portions of the novelette “Where Is the Bird of Fire?” (told from Sylvan’s point of view) published in a collection of the same name in 1970 by Ace. Ace Science Fiction Special Series 1, edited by Terry Carr, was practically legendary, having published the mass market paperbacks of several major novels, including Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness (1969) and A Wizard of Earthsea (1970), and which included some of the era’s most accomplished sff writers: Clifford Simak, R.A. Lafferty, Alexei Panshin, Joanna Russ, James Blish, Roger Zelazny, Philip K. Dick, Avram Davidson, Keith Roberts, Michael Moorcock, John Brunner, Suzette Haden Elgin, and more. Series 3 was equally impressive for publishing the debut novels of Kim Stanley Robinson, William Gibson, Michael Swanwick, Lucius Shepherd, and Richard Kadrey, among others. Series 2 was shorter-lived than the other two and not edited by Carr, but also included some major names: Marion Zimmer Bradley (acknowledgment), Stanisław Lem, and Chelsea Quinn Yarbro—as well as Thomas Burnett Swann. This series across all three incarnations saw itself as the sff tastemaker par excellence.

On Lady of the Bees’s back cover (which doubles as a series advertisement), Swann is described as “a true craftsman with a well-earned international reputation for his mystic, classical fantasies” and a quote from Theodore Sturgeon pulled from his review of How Are the Mighty Fallen (1974) in the New York Times Book Review opines: “He writes blissfully and beautifully separated from trend and fashion; he writes his own golden thing his own way.” The back cover also claims that Swann called Lady of the Bees “the best book he has ever written.” That two of Swann’s fantasy novels were included in the series (and Le Guin’s first Earthsea novel in 1970) is evidence of the changing understanding of fantasy’s place in popular fiction publishing, which even into the late 1970s still occasionally understood fantasy as a subgenre of sf or at least closely enough related to sf to be published by sf imprints. (This situation irked Swann, who didn’t like the prevailing idea in sff communities that fantasy was the “bastard brother” of sf (Collins, 10). Of course, the winds of genre were already shifting by the mid-1970s and would dramatically change after 1977, though sf fans retained some of their holier-than-thou attitudes with regard to fantasy. For more context on this period, see the discussion in the “Prelude” section of my The Last Unicorn essay and see Williamson, especially his conclusion, for the most in-depth discussion yet available on the state of fantasy c. 1975–1980.) The inclusion of two of Swann’s novels in the second Ace Science Fiction Special series and the choice of cover copy and blurbs points to the esteem in which Swann was held by the mid-1970s.

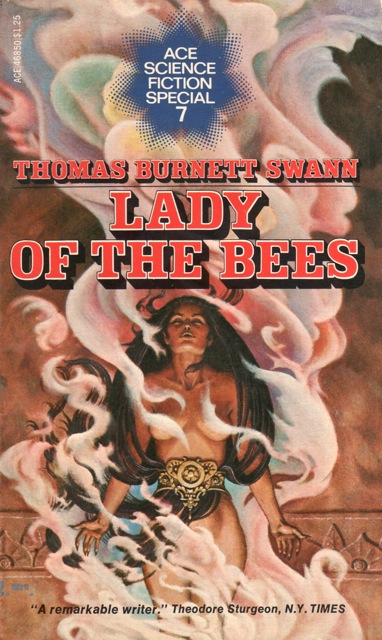

Something needs must be said about the cover of Lady of the Bees, which although beautiful, is also ridiculous and has nothing to do with the novel. The cover was painted by Stephen Hickman, an incredibly prolific cover artist in the more realist style that emerged in fantasy art of the late 1970s and which practically defined fantasy covers for the next two decades. He painted several Swann covers, including Ace’s late-1970s reprints of The Weirwoods (1967) and Moondust (1968), though Hickman is probably best known as the cover artist for most of Steven Brust’s Vlad Taltos novels (he’s done so many covers it would be hard not to recognize one of them). But the cover for Lady of the Bees was Hickman’s second cover art job to see print, the first being for the May 1976 issue of Fantastic. Hickman’s Lady of the Bees cover is certainly beautiful, in its own way, particularly the ethereal smoke in shades of blue and pink that swirl around a nearly naked woman—of questionable body proportions (where do her organs even go?!) and with gravity-defying hair and razor-sharp nails/claws—before a wall decorated with “ancient” carvings. The cover has truly nothing to do with Lady of the Bees. The woman is certainly not Mellonia, who is not unclothed in the novel (excepting one scene where she bears her breasts in an outfit referencing the Minoan Ladies in Blue fresco) and who has green hair and pointy ears (see Gray Morrow’s 1967 cover of The Weirwoods for a closer fit). Maybe, maybe Hickman’s cover could be read as an invocation of, say, the Oracle at Delphi and, by distant extension, the mysteriousness of Vestal or Lupercalian rituals associated vaguely with the narrative of Romulus and Remus. But that’s a ridiculous stretch and even at a stretch doesn’t make much sense. So I think it’s best to just say that Stephen Hickman heard the novel had a woman main character and was set in “ancient times” and he just went from there.

Finally, it’s worth noting that Lady of the Bees is generally considered the third novel in what fans and critics have come to call the “Latium Trilogy,” though the three novels were written out of order: Queens Walk in the Dusk (1977), Green Phoenix (1972), Lady of the Bees (1976). Queens Walk in the Dusk, published after Swann’s death by Heritage Press, retells the story of Dido and Aeneas. Green Phoenix tells the story of Aeneas and the invading Trojans’ conflicts not only with the indigenous Latins but also with the mythic beings we come to know in Lady of the Bees, and includes the story of Cuckoo, son of Mellonia and Ascanius, and his Centaur friend (a parallel for Remus and Sylvan). I will delve into the relationship between Lady of the Bees and these novels in my separate essays on Green Phoenix and Queens Walk in the Dusk.

Reading Lady of the Bees

Ancient myth retellings—especially through feminist and queer lenses—are currently big business in the book world (here’s a short discussion of a tiny fraction of recent ones; here’s a salient critique of this genre cycle). But they have always been an undercurrent of the Western literary imagination, from the ancient world—e.g. Vergil’s Aeneid, which synthesized long extant Greco-Roman interpretations of early Roman history and the Latins’ relationship to the Greek colonists of Magna Graecia—to the medieval period—e.g. Geoffrey of Monmouth connecting the founding of British kingdoms to Brutus, another survivor (along with Aeneas) of Troy’s fall—to the early twentieth century, where writers like Robert Graves and Mary Renault were bestsellers across the Anglophone world, to the postwar period, where Thomas Burnett Swann plowed this ever-fertile ground anew. Like Graves and Renault, like many of our contemporary retellings, Swann put feminist(-ish) and queer spins on the myths and histories he retold.

Lady of the Bees is Swann’s version of the story of Romulus and Remus, the twin brothers famously suckled by a She-Wolf (not given a name in ancient sources, just called lupa, the feminine version of lupus, wolf; later a euphemism for prostitutes), who went on to found Rome. That’s about all of the story most people know today and the twins are probably most famous from the Capitoline Wolf statue. The story gleefully mixes elements from Ennius, Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Livy, and more who wrote about Rome’s founding several centuries after they “happened,” leading to a confusing mix of possibilities about who was who, who did what, and why and so on. Swann peaks through the curtains of time, with these Greco-Roman writers as his guide, and turns their antiquarian myth-telling and speculation (some authors are more definitive about what happened, while others record the gamut of what earlier writers said happened, even when they contradicted one another) into the historical “facts” of the novel’s storyworld. I won’t detail all of Swann’s plays on and departures from sources (insofar as I could catch them), except when interestingly relevant, but for a good companion against which to read Lady of the Bees, Jaclyn Neel’s Early Rome: Myth and Society is unparalleled; it provides detailed accounts from dozens of Greco-Roman sources about nearly every aspect of the myths about early Rome, from Aeneas’s flight from Troy to the overthrow of the Roman kings and the establishment of the Republic.

Swann’s version of the myth of Romulus and Remus is narrated by Mellonia the Dryad and Sylvan the Faun. It offers two tightly controlled, voice-driven first-person perspectives that switch between the narrators, who give us different glimpses into the world of the Forest Folk and of archaic Latium. Ancient, ageless Mellonia affords us the vantage of one who has seen the world’s changes from the Saturnian Golden Age down to the present, for she has lived longer than most Dryads, has remained a guardian of the forests near the Tiber, was lover to both Aeneas and Aeneas’s son Ascanius, and saved the infants Romulus and Remus from death by exposure. Short-lived Sylvan—for Fauns age twelve times as fast as humans in Swann’s narrative—offers a more immediate and admiring perspective on Remus, Romulus, and their plans to restore the twins to rightful rulership of Alba Longa, the city founded by Ascanius 453 years earlier and now ruled by the corrupt usurper King Amulius. Both narratives are highly personal, incredibly charming in their own separate ways, and develop such distinct voices for Mellonia and Sylvan that it is, even now, weeks after finishing the novel, hard for me to forget them. But Swann is not all charm; the narratives Mellonia and Sylvan weave around Remus also have a dark edge, one of betrayal and tragedy, and turn to grand themes about the relationship between civilization and violence, humanity and nature, love and hate.

Swann opens “the best book he has ever written”—after a dedication to the actress Stella Stevens: “Inimitable in beauty, incomparable in genius, love goddess to a godless age” (n.p.)—with a “Historical Note” that says much about Swann’s respect for history and archaeology, and about his complementary vision of poetry and fiction:

The degree of civilization reflected in this novel, the architecture of temples and palaces, the sculpture of images exquisite in gold and malachite, the religion of humanized deities with great personal beauty and a very personal interest in nubile princesses, even the calendar divided into twelve months, did not belong to the relatively primitive people who created Rome. Rather, I have followed the Roman poets in idealizing their past. Most modern historians contend that Romulus and Remus were merely myths; that the first settlers on the Palatine were illiterate shepherds and thieves; that Rome, far from being founded, grew haphazardly from a village of wattle huts into a city of concrete, bricks, and marble. They are doubtless right.

Still, poetry and fiction possess a truth which eludes history: to interpret rather than record. My novel is an interpretation. (n.p.)

You can see in this plainclothes historical note some of Swann’s wry humor (mocking the gods’ “very personal interest in nubile princesses”) as well as his investment in the idea that things were not really what the poets and writers made them out to be. Rome’s founding is not really the story of grand heroes momentously declaring a city into being, as would befit the beginning of the supposedly greatest city in the West, but rather it was done by “primitive people” living in “wattle huts” around which a city accumulated. By gesturing to poetry and fiction as a different order of reality, as an interpretive mode that deals directly with the (mis)perceptions created through the mythologizing process we have inherited as the “story of Rome’s founding,” Swann sets up a fantasy world that will radically disabuse readers of the notion that Romulus was a great hero and that Rome’s origins were anything but a series of tragedies: an inevitability (because it’s our historical reality: Rome was founded) of human civilizational “progress” that destroyed something older, truer, and dearer: the world of the Forest Folk.

Into this fraught space of mythic and literary (mis)interpretation, of poetic play and fictional historicizing, so eloquently denoted by Swann, steps Mellonia—Lady of the Bees, a perpetually youthful Dryad who has lived, for reasons unknown, longer than any of her kind. The opening of the novel tells how Mellonia, courted by a Faun named Nemustrinus (a purposeful(?) misspelling of Nemestrinus, an obscure deity of groves; he is later called “Lord of the Groves” (27))—for Fauns are ever lustful—, is taken to see the execution of Rhea, a priestess of Vesta and the daughter of the deposed king Numitor, for the crime of breaking her vow of chastity. She says her lover was the war-god Mars but the usurper-king Amulius charges it was a common shepherd (the ancient sources disagree, too). Rhea is buried alive and her twin children are given to a shepherd, Faustulus, to kill. Faustulus instead places them in a boat of reeds (very Moses!) and floats them down the Tiber, where Mellonia, having tracked the progress of the mother’s execution and the babies’ fate, rescues them with her she-wolf companion, Luperca, and brings them to her tree. (In Swann’s world, Dryad’s are green-haired, pointy-eared humanoids of roughly human size who dwell in great houses grown into trees, but they are not trees themselves; Mellonia describes the relationship between Dryad and tree as one of daughter to father.)

In Mellonia’s tree, the babies—one dark-haired, she calls Little Wolf (Romulus); the other, fair-haired, Woodpecker (Remus)—are fed by Luperca and other animals, including a woodpecker who brings berries, and given “special gift[s] more lasting than food” by the mysterious, child-sized hooded beings known as Telesphori (24) (a scene very purposefully mimicking the magi visiting Jesus; myrrh is even mentioned, remarked as a lesser gift than what is given here). But Mellonia, still pained by the death of her son with Ascanius, Cuckoo, several centuries ago, makes the choice to have the twins raised among humans, and so leaves them back at the hut of Faustulus to be raised, with Luperca as guardian, and leaves a note-poem:

A god sired them;

A she-wolf fed them;

A woodpecker brought them berries.

Can you do less? (26)

The narrative then jumps forward some fifteen and more years later, switching perspectives to Sylvan, a young Faun and son of Nemustrinus who once courted Mellonia. Sylvan’s story opens with a raid on his Faun village by the shepherds and thieves who have built a village of “wattle huts” atop the Palatine. They are led by the vicious Romulus, who uses the attack on the Fauns as a wargame to hone his followers’ martial skills in anticipation of a future battle when he might overthrow Amulius and restore his grandfather Numitor to the throne of Alba Longa. Sylvan is captured and taken back to the Palatine, where he is threatened with being roasted like a goat, until he is rescued by Remus, who sweeps into Romulus’s hut, chides him for attacking the Fauns who should be given respect as Forest Folk, and takes the scared Sylvan to the cave in the forest where he lives with a now grey-muzzled Luperca (incidentally, the ancient Roman rites of the Lupercalia—the meaning and purpose of which were long forgotten by the time of the Republic—were performed at just such a cave). Thus begins a tender friendship between Sylvan and Remus, the latter of whom admires the former, sees him at times like a father figure (in some accounts Picus/Woodpecker is the father of Faunus, progenitor of the Fauns), and also feels something like a lover’s desire toward Remus, though this is never made explicit. Consider this moment, one of many such:

[Remus] rose to his feet and kissed Romulus soundly on the cheek.Yes, kissed him, a man kissing a man! Why not a soft, cuddlesome Faun who lay at his feet like a good little lamb? (42)

You can see the charm of Swann’s character-driven style oozing from this short moment, which is both endearing and probing. Sylvan’s perspective regularly contrasts the highly macho ethos of Romulus and his followers, as well as the Fauns, with the sensitive, gentle masculinity of Remus, which is associated with his love for animals and the Forest Folk, his desire to bridge the growing void between nature and humanity. A queer desire between Sylvan and Remus—largely of the former for the latter—runs through all of this but is never made explicit, only toyed with, hinted at, obliquely suggested in passages like the one above.

The bulk of the novel’s conflict centers around Romulus and Remus’s plans to restore Numitor to the throne, which requires revealing themselves as still alive and helping to orchestrate a coup within the city of Alba Longa. A feat made all the more difficult by Amulius having recruited a standing army of a thousand mercenaries from across Magna Graecia, which he pays for by levying tyrannical taxes on the Latins. Romulus has an army of only a few dozen men, none with armor or weapons, and none trained in conflict except a few disreputable types driven out of even Amulius’s service. Among these is Celer, a lecherous swine who represents the apotheosis of Romulus’s worst character traits; he was in fact the guard who ordered Faustulus to kill Rhea’s twins (though he doesn’t know it). Celer is to Romulus as Sylvan is to Remus—a confidant and supporter, though Romulus sees Celer in largely instrumental terms as a weapon to wield against Amulius, whereas Remus views Sylvan as a friend, brother, compatriot. These are but two examples of the excellent characterological doublings Swann structures throughout the novel and which serve to reinforce the civilization/nature divide, though Swann tempers the opposition with shades of intensity.

The narrative proper picks up a year or so after Remus rescues Sylvan, the latter now fully grown in Faun years. Romulus is anxious to overthrow Amulius but they have no real means of defeating him. In the meantime, Remus is anxious that his bee colonies are dying and so follows the advice of a Nemustrinus to seek help from the Lady of the Bees, Mellonia. When Remus at last finds her tree and her, he falls in love—and ageless Mellonia, despite her years and past experiences with human lovers, despite having acted in some small way as Remus’s foster mother, falls in love with Remus, just as she did with Ascanius (Remus’s ancestor) and Ascanius’s father Aeneas. Sylvan is, of course, at first jealous of the attention Remus gives to Mellonia but soon comes to love her, too, albeit platonically. Mellonia has an understandable wariness of Fauns (who have tried to woo her for centuries, as Sylvan’s father Nemustrinus did) but she is chided by Remus for imagining that all beings of a species or race are of one kind, and it is Remus’s deep compassion, not only for Sylvan, but for all Forest Folk and animals—that is: for nature—that leads Mellonia to fall in love a third time. Mellonia’s patterns of behavior (the story of her earlier loves is told in Green Phoenix from 1972) play a key role in Lady of the Bees, and it is partly her adherence to that pattern—following her desires, again, with a human hero—that leads to tragedy for both her and the hero (again) (this is explored more deeply in the next section).

Eventually, Romulus realizes they won’t be able to take Alba Longa by force and so must devise another plan that relies on cunning and the will of the people to overthrow the tyrant Amulius. The idea is for Remus to infiltrate the palace, find their grandfather Numitor, and reveal that the twins have survived; and then, with his blessing, encourage the people to rise up against Amulius and restore Numitor to the throne. But this doesn’t go as planned: Remus indeed meets Numitor and convinces him that the time to overthrow Amulius has come, but Remus is captured and imprisoned by Amulius before he can escape back to the Palatine. Sylvan, aware that Romulus can do nothing to save Remus, tells Mellonia, who first consults the mysterious Telesphori for aid (more in the next section) and then rallies the forces of the forest—an army of wolves!—to invade Alba Longa alongside Romulus’s ragtag army of shepherds, cutthroats, and thieves. Together, they overthrow Amulius and free Remus, as well as a number of mythic beings (e.g. a Centaur and a Triton) who were kept caged in the palace for Amulius’s amusement and as a symbol of his hatred for the non-human, natural world (we might also read this as a perpetuation of Aeneas’s legacy, and thus the legacy of human civilization in the midst of a prehuman world, since on invading Italy in Green Phoenix, Aeneas fought against the prehuman beings in order to establish a foothold for his lineage that would lead to Alba Longa; in this vein, here is another doubling worth considering: Amulius : Numitor :: Romulus : Remus).

In the aftermath of their victory, the restored king Numitor has no desire to turn over rulership of Alba Longa to Romulus and Remus, in large part because he fears Romulus and does not trust him to be a good ruler. So he instead gives the twins permission to establish their own city, which they will rule over as co-kings (not unlike the two kings of Sparta, whose family lines were said to be descended from the twins Eurysthenes and Prokles, descendants of Herakles). Romulus and Remus have a contest to see which of the hills they prefer will be the founding place of their new city: the Palatine of Romulus or the Aventine of Remus. It is the latter where Remus hopes to build a city that will bring together humans, Forest Folk, and animals, on a hill blessed by Rumina with a fig grove and Vaticanus with a rock in his likeness (both were minor gods of birth and beginnings). The contest will be judged by the gods, who will bless the site of the new city with omens of vultures. Remus and Sylvan, atop the Aventine, see six vultures. When they tell Romulus, he lies and says he saw twelve. Remus cannot bear to call out his brother, though he knows the truth of the lie, and so allows the building of the city on the Palatine to begin: “The hill is not important,” he tells Sylvan. “Romulus lied. That is important. He is building his city on a lie and the men know” (179).” About his betrayal, Romulus has no qualms: “I looked for guilt and saw dominion,” says Sylvan (185).

But in the midst of a celebration for Mars, Celer and two criminal companions sneak off to rape and kill Mellonia, leaving her and her oak “ruins now, ruin upon ruin” (182). The crime is both gendered, drawn from a long tradition of such “fridging” in sources ancient and modern, and also representative of humanity’s final, violent conquest over the natural world, destroying the last vestige of the Golden Age of the gods and prehumans that lingered in the forests of Italy under the watch of ageless, ancient Mellonia (“She opened her eyes and kingdoms stared at us—Troy, […] Carthage, […] a city in search of a name to bestride the world” (183)). This betrayal by Celer is meant as the apotheosis of the earlier betrayal by Romulus, proof that the ideology driving the human founders of Rome is one of greed and destruction. It is captured poetically in a brief exchange between the grieving Sylvan (the “I”) and Remus:

“Why do they hate flowers?” I cried.

“Not just flowers.”

“Growth?”

“Because they are—stunted.” (183)

Swann further contrasts the ideology that leads to such violence. Shifting to the scene where Remus confronts Romulus over Celer’s betrayal, Sylvan describes the raising of the new city’s walls in violent language, as an aggressive war against the soil and rock to stake the foundation for the city’s walls—labor accompanied by songs that lionize Romulus as the son of Mars, child of the (now unnamed) She-Wolf. Sylvan remarks, “Heroism, it seemed, meant to hurl a spear and capture a throne, not to make laws and serve the gods. Swords, not staffs. Wolves, not birds. Romulus, not Remus” (186). When Remus arrives back at the Palatine to confront Celer, he steps over the boundary line of the new city drawn by Romulus (a bad omen for the city); his visage is so enraged he looks like Mars himself. But warlike and selfish Romulus does not listen to Remus’s accusations against Celer; he cares only for the bad luck Remus has brought him by breaking the boundary line before the wall has been built, and so challenges Remus to a fight:

Remus turned to Romulus but not to fight. To speak. I saw him start to speak his brother’s name. I saw the flight of Mars [from his visage]; the temple indivisible, the gentle god restored to deity.

He turned into the moving shovel. Romulus, I think, had meant to strike his arm, his threat to Celer. He caught the metal in his face. The blow was meant to stop; at most to stun.

He caught it in his face.

The perfect features did not dim; the wide green eyes stared Dryad trees and Silver Bells [a reference to Sylvan] and, at the last, surprise, as if to say,

“But I am Remus…”

The hair, that miracle of sun, did not forget its fire; still, something was gone,

The luck from a city,

The light from a lantern shaped like a moon,

The woodpecker from its nest in the hollow tree.

He did not say goodbye (Remus, I can forgive your not outliving me, but no goodbye? It was not like you, friend. Memory feeds on morning’s manna but at the last must starve for one good-night. (189)

When Remus becomes, in a word, like Romulus, he prompts his twin brother to react in kind—for brute force only knows brute force—and so delivers a blow, accidentally or not killing Remus.

In the end, Celer sneaks away with his criminal companions and is killed by the Telesphori. Romulus returns Remus to the cave in the forest where he and Sylvan dwelt, near the fig tree and the shrine of Rumina, companioned at the side of his catafalque by his foster-mother Luperca, who shuns Romulus. Romulus weeps (“Kings weep. Little folks cry,” Sylvan reminds us (196)) in shame and sadness but vows to Sylvan to build Rome at least partially in Remus’s image:

“He was all I needed of gentleness. Now he is gone—unless I resurrect him in our city. A second Troy, Sylvan. Men will call her Rome to honor me and fear her legions in the ancient great—Carthage and Karnak, Sidon and Babylon. But her roads will carry laws as well as armies. Scrolls as well as spears. Sylvan, don’t you see? Remus will live in us. In Rome. Come back with me, little Faun!” (197)

Which brings us to the epilogue, quoted at the beginning of this essay. An end that we might attribute, perhaps, to Sylvan, who witnessed Mellonia call Remus the Bird of Fire in her dying moments, and who no doubt would seek out the divine presence of his friend wherever it could be found. Or perhaps we might attribute it to Mellonia, now a lemur, a spirit of the dead (like her aunt Segeta), as she begins her journey to seek out Remus in the afterlife. Whoever the speaker, the epilogue gives us some glimpse of a possible future for Rome, where “Fauns can walk with men,” where the thunder of the woodpecker’s wings can be heard (a city of birds, not wolves; or perhaps birds and wolves). A place where dwells the spirit of Remus, the Woodpecker, guardian of a possible future Rome where Forest Folk and humans can live side by side in harmony.

Or perhaps that is wishful thinking: the hope of the dead—or the dying; Swann was, at this time, dealing with a second bout of cancer that would kill him the same month this book published—for the living: a world better than the one before.

In the Fading World of the Forest Folk

The world of Swann’s Forest Folk in Lady of the Bees is a world of fantasy drawn from Greco-Roman and Etruscan traditions but infused with the textures of modern fantasy fiction. To use a linguistics metaphor: Swann’s world is a creole: the vocabulary of ancient myth structured by the syntax of modern genre fantasy and its inheritances from adventure fiction, historical romance, and Victorian fairy tales. We might compare Swann, in this regard, to Williamson’s reading of Poul Anderson’s The Broken Sword (1954):

The Faerie realm is treated in an implicitly speculative fashion, like a parallel dimension in the same geographic space as the human world but invisible to humans. The structure of the Faerie world is also […] neatly diagrammatic. Aesir and Tuatha de Danaan, Elves and Sidhe folk, coexist in the cosmos of Sword, rooted in, respectively, Germanic/Scandinavian and Gaelic dominated areas—something alien to either traditional Germanic or Celtic sources. The Germanic end of Faerie breaks down clearly into Elf, Dwarf, Troll, and Goblin, each with their respective societies. (184)

While Swann’s “Faerie realm”—that is, the world of prehuman mythic beings—is not a parallel dimension to that of the human world (except: see below), it is in some sense distinct, different, older, and dying out. Indeed, the people of Latium know little of the Forest Folk and, ancient and mythic as the Etruscans and Latins seem to us, they think of the Forest Folk mostly in mythic terms. Fauns are really the only Forest Folk humans regularly come into contact with; Mellonia herself is thought to be a myth, and one hardly understood even by Romulus, to whom “[a] Dryad was a girl with pointed ears,” no more (193). In one reading, Swann is simultaneously modernizing the Greco-Roman myths by bringing them into the fold of genre fantasy—intermixing mythic traditions, giving each prehuman species “their respective societies” like the elves, dwarves, and hobbits of Tolkien D&D, and beyond—while at the same time critiquing the very “domestication” of such mythic figures by pointing to the way that men like Amulius, Celer, and Romulus strip them of their magic and mystery, one for entertainment, one for defilement, and one because of his belief in the supremacy of humans.

While Swann might be read as explaining the supposedly non-realist elements of mythology by bringing creatures and beings from ancient myths into the speculative, diagrammatic worldbuilding of genre fantasy, Swann’s fiction are decidedly not attempts to replace the fantastical elements of the taproots of genre fiction with something more akin to realism. Swann felt that contemporary authors were “monumental failures when they treat the ancient myths” because they tried to “rationalize the legendary beings, or superimpose mythic patterns on modern characters” (first is a quote from Swann, second is Collins’s own words; Collins, 2). He admired Mary Renault, one of the twentieth century’s most prolific mythic retellers, but felt that she took “the supernatural out of mythology—for example, when she explains the centaurs as being no more than shaggy men on horses” (quote from Swann; Collins, 2). For Swann, the Centaurs are one of many prehuman peoples, like Dryads, Telesphori, Fauns, Minotaurs, and more, who read like the elves and dwarves and hobbits of Tolkien: peoples fading into the mythic past as humanity increasingly takes center stage. Coincidentally, Swann only ever read The Hobbit and admired the effort but read no further (see Collins, 1–2); one wonders how he would have felt about The Lord of the Rings, especially had he known that Tolkien’s fantasy was deeply engaged with European history, mythology, and philology, and that The Lord of the Rings had a great deal of thematic resonance with his own work (though he probably would have wondered why the men weren’t queerer and where the women were).

Swann’s fantasies of the prehuman world are ultimately tragic, because they implicitly acknowledge that the grand world of magic, mystery, and myth have been quelled by the rise of human civilization, of reason and rationalism, and of the valorization of the masculine ideal over the feminine. The changing nature of the world is made all the more tragic because Swann narrates his fictions from the perspective of non-human characters, like Mellonia and Sylvan, allowing us to glimpse their world more readily and to grieve with them for what it was, rather than following heroes blindly into a future that thinks of the prehuman past as, perhaps, a Golden Age, yes, but one that is fundamentally estranged from humans like Romulus and therefore not particularly relevant to their lives. Sylvan notes, for example, that for Romulus the gods are not exactly real beings, but tools for humanity to use: if he observes the right rituals, he will get XYZ in return (193).

Swann deploys his narrators to make this point about the difference between the world of myth and the world of man (a purposeful gendering), but it also becomes a worldbuilding strategy that shifts our perspective from the relationship between myth and man in the novel to the relationship between modernity and the past, or between the real and the fantasy, as mediated by the novel qua novel. This is best evidenced by Swann giving importance to names and figures that, for the most part, are minor (sometimes really minor) references from ancient sources: not only Picus and Faunus, but especially Nemustrinus, Vaticanus, Rumina, Minutius, and Telesphorus (discussed below). Many of these are taken from ancient Roman indigitamenta (even Mellonia is repurposed in this regard) and many are also divine functionaries (that is, figures who personify a certain domain, as Vaticanus does the birthing process, specifically whether a baby cries, or Mellonia does honey). This worldbuilding choice—which displays Swann’s depth of knowledge and the inventiveness of his imagination to bring to life such minor figures and in such idiosyncratic ways—has the effect of estranging the reader from the familiar texture of the mythic retellings, which we might expect to look like what the ancient Roman and Greek sources focus on (or what we are familiar with from other retellings). Swann reveals what we know but don’t often emphasize: the texts we have show us only a tiny fraction of the complex social, religious, and political world of ancient peoples—all the more so when what we have is just the fragments of what even ancient authors could gather about times that were, to them, very long ago. Swann’s vision of Bronze Age Italy is thus welcomingly strange, not unlike what a historian of archaic Rome, steeped in what knowledge we can glean from surviving texts and material culture, might experience if they could time travel there.

Central to Swann’s appropriately strange vision of mythic past is the image of the feminine divine, evident most clearly in Lady of the Bees’s admiration for in not veneration of Mellonia, though it looms large across his fiction. Indeed, in a 1969 essay about Edgar Rice Burroughs, Swann concludes: “Never apologize for reading a man who sculptures goddesses and never trust the critic who attempts to melt them” (“Prodigal Praises,” WSFA, no. 64, Jan. 1969; see the Black Gate article, “The Burroughs Boom,” for images of the essay). Swann is specifically interested in the platonic form of the feminine as embodied in figures like Burroughs’s Dejah Thoris, the eponymous princess of Mars. Many of Swann’s novels feature a protagonist of this sort: a strong, independent, sexual, and, yes, usually buxom woman. (Unsurprisingly, Swann was a fan of classic Hollywood stars, wrote about them regularly in fan magazines, and dedicated several novels to stars like Stella Stevens.) This is, of course, an objectified and in many ways problematic vision of femininity and womanhood—and one repeated in some feminist visions of the “mother goddess” or the “feminine divine”—and is complicated by Swann’s elusively queer relations throughout his oeuvre. It is also doubled in his admiration for male beauty and bodies. His is the (imagined, idealized) Weltansicht of ancient Greece, where physical human forms are representations of inner qualities. But this approach to beauty and physicality is not so simple, since Swann admires, say, the physicality of Romulus but seems to despise Romulus himself or set him up, at the very least, as the antithesis of what is truly good. Moreover, Swann’s admiration for idealized physical representations of femininity and masculinity lean heavily toward the feminine: it is women, and men associated with more feminine qualities, and in particular the attachment of femininity (at least in Lady of the Bees) to nature (but, importantly, not nurture) that provide an ethical throughline and answers to the problems of civilization. Swann’s reading of ancient history, mythology, and gender thus rhymes with the interpretations that emerge in the writings of disparate intellectuals like Marija Gimbutas, Starhawk, and Riane Eisler and which are heavily associated today with spiritual feminism, ecofeminism, and (neopagan) goddess worship.

This swirl of complicated ideas about gender, sex(uality), and bodies in Lady of the Bees is intimately tied to what for Swann is a foundational opposition: the conflict—variously natural, social, and political—between civilization and nature, between humanity and the pre-/non-humans. We see this play out in the final betrayals and conflicts between Romulus and Remus, where Celer represents the logical extreme of a highly gendered understanding of the world, one where physical might, lust, and power are aligned with the masculine, with Mars; and beauty, laws, learning, and nature are aligned with the feminine, with gods of beginning and childbirth like Rumina and Vaticanus, or with the god of “minor things,” Minutius. Romulus, Celer, Amulius—civilization, humans—on the one side; Remus, Sylvan, Mellonia—nature, the Forest Folk—on the other. The conflict is written into Swann’s very worldbuilding strategy and his approach to myth retelling, which casts the rise of human civilizations and the acts of great heroes not as triumphs, but as tragedies. I’ve detailed a number of scenes and moments in the above section, using Swann’s own language, to draw out these themes in his work. But of particular interest here is the role of the obscure beings known as the Telesphori, who offer perhaps the most important commentary in Lady of the Bees on the novel’s grand themes of conflict.

Although they are significant to Mellonia’s story, the Telesphori are also really a strange addition to the narrative and wonderful evidence of Swann’s occasionally truly idiosyncratic imagination (as well as his ability to take the ostensibly ridiculous and make it simultaneously charming, emotionally weighted, and thematically significant). As noted above, the Telesphori are child-size, hooded figures with tails. Mellonia initially describes them:

The Telesphori live in the Valley of the Blue Monkeys. Their hooded figures reflect the secrecy of their land. It is ruled by a king who sits on a throne of teakwood and takes tea while he dispenses justice. It is a land of wind chimes sweeter than lyres and strange animals like piebald bears [i.e. pandas], and trees which grow like intertwining snakes. It is a valley but also a way. The Telesphori exchange gifts as other folks exchange truth. (24)

And we get no more explanation for nearly 100 pages until Mellonia decides that the answer to how to save Remus, without Romulus and his men all dying against the greater enemy of Amulius’s mercenaries, might rest with the King of the Telesphori. Mellonia’s visit to the Telesphori is one of the longest single chapters in the novel (114–130) and describes her journey into the Valley of the Blue Monkeys, a place that is spatially incongruous with the region of Latium and is accessible only with a Telesphorus as guide. It is a zone described as though it were transplanted almost from another world (akin to the parallel dimensions of faerieland mentioned by Williamson above). As Swann notes in the Acknowledgements, it resonates with James Hilton’s Shangri-La (nestled in the Valley of the Blue Moon) in Lost Horizon (1937), though Swann states that he was explicitly not inspired by Hilton, that he only discovered the connection later, and he chalks the similarity up to their both having “imitated the same Utopian myth” (199).

In Mellonia’s description, “The Valley was not of the forest, it hid within the forest, like Hope in Pandora’s Box” (114). When Mellonia enters the Valley, escorted by the Telesphorus Lordon (one of the gift-givers in the magi-like trio above), Swann gets formally inventive with his prose to mark the transition between the world of Latium and this other space of the Telesphori:

I followed him down the serpenting path

…into a woodland which did not seem to have grown, so surely, so perfectly did it grow, bend, curve; rather, it seemed a water greener than tourmalines and frozen in its leap: trees sweeping upward and upward and curved at the top like a great, breaking wave eternally caught in its fall; mahogany, palm, and cork; and flame tree, liquid sun at the crest of the wave. (116, unusual line break and ellipsis in original; “…into” starts exactly where “path” ends on the line above)

Swann gives multiple paragraphs to the description of the Valley, its forest, its trees, its architecture, and more, especially the “monkey puzzle tree” the Telesphori dwell in (though I’m not sure Swann means this, since it doesn’t seem like a very comfortable tree to make a home in). We learn that the Telesphori are refugees from the East, having been driven out some time ago (by humans? unclear) and made a home here in Latium, the last of their people. Their culture is also indisputably influenced by that of Asia broadly, displaying cultural aspects taken from East, Central, and South Asia and the Himalayas (and across a range of historical periods, mostly postdating the era during which the novel takes place). The Telesphori have shrines called pagodas, a palace carved from cork (a Chinese art, though usually reserved for miniatures), a great library containing all the world’s knowledge on palm leaf manuscripts (cf. Sakya Monastery, Nalanda, or Kizil Caves); the king wears a “kimona” of silk (123), drinks arak and tea, references yin/yang without naming it as such, prunes a bonsai garden, has a pet panda, and more. In addition, the Telesphori worship a Zoroastrian god named Tishtar (notably, the three magi who visited Jesus are often considered Zoroastrians), have incredible astronomical knowledge (there are references to Babylon, which in the West was the originator of astronomy and astrology), and they have a nearly globe-spanning knowledge of the natural world, referencing creatures like kangaroos and raccoons (Australian and New World animals, respectively). Most curiously, the hooded Telesphori are all men; the women are the palm-like trees that dot the Valley, and their children grow from their coconuts (I suppose this means that the palm-leaf library is made from the women’s hair?).

Of course, this being Swann, the Telesphori have some basis in ancient Western mythology. There was a god, Telesphorus, who was a hooded, child-size figure associated with healing, who may have been Celtic in origin but was transposed into worship across Magna Graecia by Celtic migration in the 3rd century BCE, and who remained a minor god of healing for hundreds of years. There were also minor deities called Hooded Spirits, of Celtic origin, whose representations are spread throughout the Greco-Roman world during the same period as Telesphorus. Often they were represented in groups of three (cf. the three Telesphori who bring gifts). So Swann is radically intermixing ideas from Asian, Greco-Roman, Celtic, and Zoroastrian cultures to bring to life a prehuman people that is both idiosyncratically his own creation and also deeply indebted to material understandings of ancient cultures and religious practices—only, with the Telesphori he has turned his usual repurposing of ancient mythology up to eleven and created something completely new, utterly odd, and strangely compelling. At the same time, they read like the worst excesses of the kind of Orientalism that casts “the East” as a placeholder for critiques about the West and as an alternative to modernity (see my essay on Tuleja’s Land of Precious Snow, especially the section “Seventies America, Rampaism, and Land of Precious Snow”).

The King, ultimately, has very little to offer Mellonia except to note that, while she is considered by all of the remaining Forest Folk as their queen, she has become reclusive since the death of her son Cuckoo some 400 years earlier and, as such, has done little to defend the Forest Folk from humans’ encroachment. Moreover, the King chides Mellonia and “you of the West” for an obsession with time, urgency, perfection, and epistemological efforts to quantify and name everything (despite their vast library!). He declares that the fundamental difference between “we of the East” and “you of the West” is that the former “know what we do not know” while the latter attempt to reduce everything to “tidy patterns.” He reminds Mellonia that the Telesphori “have endured since before the Flood because we are one with the earth. We do not conquer nature, we grow with her” (120).

In the end, the King refuses to aid Mellonia in rescuing Remus:

“He wishes to be a king. There are far too many kings. Their armies beleaguer our forest on every side. Etruscan, Latin, even Greeks to the south. That, I think, is why the forest appears unresponsive to you. You they remember and love—still. But he is a man. They are afraid of him. After all, those other men you loved, Aeneas and Ascanius, each of them built a city which still endures, Lavinium and Alba Longa. The second, a hated place. Suppose the forest helps you to crown another king. And you forget—yet again—and retire to your tree to pray for sleep. What have they gained? Only the risk of another incursion, another tyranny.” (127–128)

Mellonia protests: “Remus will be a gentle king. The forest is in his blood,” she claims—and all we have seen of Remus suggests she is right (128). The King, however, declares that she, like all those of the West, works in patterns and therefore he cannot trust that Remus will be different from Aeneas or Ascanius; to deny her further pleas for help he turns to his bonsai garden and ignores her. Mellonia is led out of the Valley of the Blue Monkeys by Lordon, but not without petting the purring panda, that “living parable” of “inharmonious harmony” (124, 123).

Unaided by the King (he is always referred to with a capital letter, to distinguish him from the human kings), Mellonia resolves to break the pattern he has ascribed to her actions and so rallies the animals of the forest to aid her and Romulus in taking Alba Longa: a literalization of Remus’s vision that the human world they can build will accommodate humans, Forest Folk, and animals alike. For her victory, for changing her pattern and thus the cycle of violence that has shrunk the realm of the Forest Folk, the King gifts her the panda. But the panda, whom she names Bounder, later returns to the Valley in a moment that foreshadows Mellonia’s death and Remus’s betrayal by Romulus: “I thought of a city whose luck departs to the piping of a sorrowful tune,” she thinks, as she watches the panda leave (172).

What Mellonia does not recognize is that in helping Remus she is also—and perhaps more importantly—helping Romulus. Though she is determined to break her pattern and overturn the opposition between civilization and nature, she overlooks Romulus and the treachery of his followers. In doing so, Mellonia brings about her own death and, by extension, Remus’s. What results is the worst fear of the Telesphori speaking on behalf of the Forest Folk: that another Lavinium or Alba Longa will rise up without challenge from their queen. In a world where the queen of the forest no longer abides, where she has been betrayed again and slain by humans, the Forest Folk cannot hope to survive. In lamentation of this fate—perhaps in recognition of Mellonia’s efforts to change the pattern—the Telesphori kill Celer, but no more. They return to their Valley as Rome rises.

The world is no longer for Telesphori, no longer for those who “are one with the earth”; it is no longer a world for pandas, but for humans and cities, armies and wars, and maybe those few—like Sylvan—who try (in vain?) to build Remus’s vision in the midst of Romulus’s city.

The Inevitability(?) of Rome

Thomas Burnett Swann’s Lady of the Bees offers a direct political and ethical response to modernity by way of its inventive fantasy retelling of the mythological founding of Rome—its remixing of a moment of supreme importance in the history of the development of “Western civilization.” It is also deeply invested in an almost ecofeminist vision of the world that critiques masculinity and violence and holds up as alternatives beauty, art, learning, compassion, friendship, love, and the inharmonious harmony between nature and civilization. Though he does not live to see it, Remus’s plans for the twins’ future city anticipate an ecotopian vision of humans, animals, and Forest Folk living in harmony, governing through representative democracy, filled with gardens and groves. Romulus’s is the antithesis: war and power and greatness, but little else besides.

But what does the end mean? What is Romulus’s change of heart upon Remus’s death, and can it be trusted? What are we to make of Sylvan’s inclusion in Romulus’s vision of Rome? Do we trust Romulus now? How does the end relate to the larger ethical and, specifically, ecological vision Swann has in Lady of the Bees? Why does the epilogue suggest that Fauns abide in Rome? I leave these questions to you and to myself, since they will no doubt come up again in Swann’s work and there is much more to say about both Swann’s entire oeuvre and Lady of the Bees than can be written in one essay—and that’s as it should be! After all, look at how much argument has been raised up around Tolkien.

But I might venture one answer, just as a beginning, to this complex of question: with its ambiguous ending, with his suggestion that Fauns will roam Rome, that perhaps Romulus’s city will be a mix of both brothers’ ideals (though we know the history), perhaps Swann wants to say—at the end of his own life—that history itself is neither wholly utopian or dystopian, but some mix, a synthesis, an inharmonious harmony of oppositional forces: actual history, shorn of prophecy.

That might be too simple an answer, and I’m not wholly convinced by the simplicity of such a conclusion for a book that, despite its brevity, has so much to say. But it’s a start. And a start, at the end, is appropriate for a book that ends at the beginning, with the idea of Rome; that valorizes Rumina and Vaticanus, the favored gods of Remus; and that reminds us, as the King of the Telesphori does, to pay greater heed to Minutius, the god of small things.

To get notifications about new essays like this one sent directly to your inbox, consider subscribing to Genre Fantasies for free:

17 thoughts on “Reading “Lady of the Bees” by Thomas Burnett Swann”