The Tournament of Thorns by Thomas Burnett Swann. Ace Books, 1976. Ace Science Fiction Special 8.

Also read by this author:

Lady of the Bees (1976)

Table of Contents

Reading The Tournament of Thorns

Mandrake Horror and Crusade Fantasy

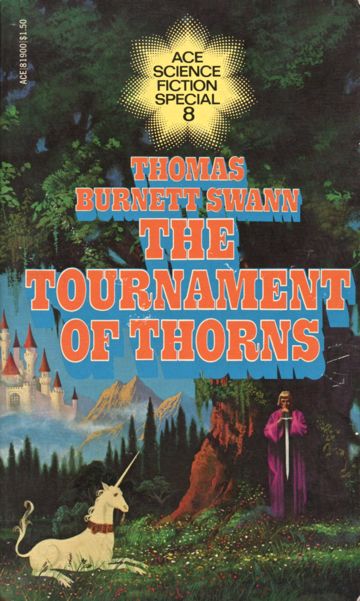

The Tournament of Thorns …by Its Cover

The Tournament of Thorns was the third-to-last book written by Thomas Burnett Swann and was published in July 1976 two months after his death from cancer. It is technically a fix-up novel expanding on two novelettes published in the The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction—“The Manor of Roses” (Nov. 1966) and “The Stalking Trees” (1973)—and was published as the eighth entry in the Ace Science Fiction Special Series 2 (1975-1977) after Swann’s Lady of the Bees (1976). In my earlier essay on Lady of the Bees I discussed both the significance of the Ace series and Swann’s publication in that series, which recognized Swann as a singular voice in the early era of genre fantasy who, as Theodore Sturgeon put it, “writes blissfully and beautifully separated from trend and fashion,” producing “his own golden thing” (back cover copy). The Tournament of Thorns is no different in this regard, and is both unique among medieval historical fantasy and within Swann’s own extensive oeuvre (as a reminder: he published sixteen novels and two story collections between 1966 and 1977, the last three novels posthumously).

The Tournament of Thorns is historical fantasy set in early-thirteenth-century England, during the reign of King John, at a time when (as Swann would have it) the crusades were as much on people’s minds as Vietnam was on the minds of Americans in the late 1960s/early 1970s. The novel is concerned at a distance with the crusades as a window into the ethical meaning of Christianity in a time of religious (and racial) violence. Within this frame, it is also a unicorn story and a folk horror tale that draws on elements of British fairy lore, stories about changelings, medieval and early modern folklore about mandrakes, the figure of the Green Man, and the idea of the vampire. England is also rendered in this novel not as a singular, static medieval nation of people calling themselves British (or English), but as a place with a complex and diverse past—composed of layers of Briton, Roman, Anglo-Saxon, Viking, and Norman habitation and invasion, as well as the prehuman elements familiar to Swann’s oeuvre but transformed here into something quite different—that linger in landscape, social structure, and political life of the novel’s world.

Reading The Tournament of Thorns

The Tournament of Thorns is a short novel divided into three parts; the first two are roughly equal in length at c. 60 pages each and the final is 40 pages. Part I: Stephen is nearly identical to the 1973 novella “The Stalking Trees”; the earlier 1966 novella “Manor of Roses” is adapted into Part II: John and Part III: Lady Mary, with some changes to connect the two stories and move the prologue of “Manor of Roses” to the beginning of Part I.

Part I introduces us to three principal characters, youths between 12 and 15ish (it’s a bit unclear). Stephen, the oldest, is the strapping straw-haired Saxon villein who lives with his parents on a farm, a subject of the feudal Norman lord Baron Ralph. Miriam is of similar age; beautiful, friendly, and kind, and one of the few girls who never gives into Stephen’s advances. John, twelve, is the brilliant, soft-hearted son of the Baron; his mother has recently died and he’s incredibly lonely. The novel opens with a prologue by Lady Mary, describing how her own son died following the shepherd boy Nicholas in the disastrous Children’s Crusade of 1212 some years ago; the prologue leaves us only with the ominous foreboding that Stephen, John, and a girl will eventually arrive at her manor. But the story proper begins with Stephen’s trip to town for the market day, where the young daughter of family friends, Rebecca, is accused by another family of being a Mandrake. They try to kill her, but Stephen and others prevent them, and Stephen, Rebecca, and her parents go off for a picnic. Unfortunately, Rebecca, unknown even to her, is a Mandrake, and she unwittingly drains some of Stephen’s blood when they are all taking a post-picnic nap. The accusers return and mob justice prevails, with Rebecca dead and her green blood as visible proof. In an indiscriminate act of retaliation, Mandrakes from the forest raid the village later that night and kill Stephen’s parents.

Unlike most of Swann’s novels, The Tournament of Thorns does not involve what his readers came to call the “prehumans,” i.e. the Dryads, Centaurs, Minotaurs, Tritons, and so on: mythological creatures rationalized into fantasy “races.” The Mandrakes are very much not like the prehumans of Swann’s novels set in and around the ancient Mediterranean, since they are not portrayed as beings belonging to older, nobler peoples who are displaced by the rise of human civilization. The Mandrakes are, instead, figures of folk horror drawn from medieval and early modern ideas about the mandrake root, which, because of its similarity in shape to the human body, was often considered a kind of malevolent being. Here, Swann has merged the idea of the Mandrake with that of the changeling from Victorian (and earlier) fairy lore and which is present in many European cultures (this is a significant plot point early in Black Book). Because female Mandrakes look very much like humans when first born (the males are too hairy and have massive dongs, a reference to the traditional use of mandrake root as an aphrodisiac), the Mandrakes will occasionally leave their daughters with humans, either switching them out and eating the human baby, or leaving them to be found and cared for. The Mandrakes then grow up among humans, learn to speak (Middle) English, and, as they slowly feed off of humans, their insides become more human-like until they are essentially indistinguishable; many Mandrakes raised among humans don’t know they are human. Mandrakes are otherwise described as looking like the folkloric figure of the Green Man: they are tree-people. Swann’s Mandrakes are also vampires of a sort; the narrator (Lady Mary) clarifies that they are not the kind of vampires found in Hungary, who cannot abide the daylight and drink blood with their fangs, but rather Mandrakes drain blood subtly through contact with human skin, feeding by touch. Finally, there are suggestions throughout the book that perhaps the Mandrakes were once like the prehumans of Swann’s ancient mythistory novels, but that contact with human civilization and the violent treatment of prehumans seen in his earlier novels transformed them into something monstrous. The possibility is enticing and fits with Swann’s larger ecological ethos; I explore it more in the section below. (For a full description of the Mandrakes, see 99–103.)

After being orphaned by the Mandrakes’ attack on his family, Stephen moves into the castle of Baron Ralph to become his dog training and kennel keeper, and there Stephen and John grow to be close friends. Together with Miriam, whom Stephen desperately tries to court, they embark on a journey one night to find a unicorn; they believe a unicorn could lead them to the Mandrakes so Stephen can have his revenge. Stephen is, after all, obsessed with the crusades and with the ancient Macedonian king Alexander the Great, and envisions slaying the Mandrakes as fulfilling his duty to his parents, while also proving him a warrior skilled enough to overcome his peasant status and at the same time serve as training should he make it to Jerusalem to join a new crusade. The plan to find a unicorn goes awry when Stephen and John encounter some hunters who viciously murder a baby Mandrake and, later, the trio accidentally sleep in a Mandrake nest and, taken as the baby-killers, are attacked. But Part I ends on a high note with the trio discovering a unicorn (thanks to Miriam’s virginity) who leads them to a (mystically concealed?) glade where dwells a whole herd of unicorns frolicking in the sunshine. (Notably, Swann’s is the medieval vision of unicorns—male symbols of Christ and the warrior ethos—not Beagle’s). Here in the unicorn glade the characters share a transcendent, transformative moment as the section ends, their would-be crusade against the Mandrakes forgotten.

Part II jumps the narrative forward some months. Plague has swept through the countryside and apparently killed Miriam. No more is said about this. This represents the gap in the novel between the two previously published novellas; Swann had to figure out a way to make them fit together, and so awkwardly devises that Miriam should die and, on her deathbed, have a vision from Hermes (curiously, not God or an angel) foretelling that Stephen and John will have “other journeys, I think, another guide. Perhaps Jerusalem…” (68). The further journey and the other guide come as one in the shape of a new girl, the same age as Miriam, and of course just a beautiful, named Ruth (a curiously Jewish name for thirteenth-century England; then again, so is Miriam! The former might be a nod to Swann’s desire to have written a novel based on the biblical tale of Ruth, though he didn’t live long enough to do so). John and Stephen find Ruth in the collapsed ruin of a Roman Mithraeum, an ancient site for worshipping Mithras. Stephen believes her to be an angel and takes it as a sign that he and John should leave their life behind, travel to London, then to the Continent, and go on crusade. John agrees; he is already on the outs with his father and his knights for failing to live up to their violent, brutish ideal of masculinity, for being bookish and gentle, a “girl” they call him.

We’ve seen the juxtaposition of gentle and aggressive masculinities before in Swann’s writing, for example in Lady of the Bees. Though here in The Tournament of Thorns that dynamic is nuanced a bit more, with John’s father standing in for the excesses of what we might today call toxic masculinity, John representing the soft, gentle masculinity Swann so admired, and Stephen being a figure of strength and brawn tempered by a measure of tenderness and kindness. Moreover, just as in Lady of the Bees, the relationship between Stephen and John is shot through with homoeroticism; but where it was subtle, cutesy, and nearly missable in the story of Remus and Sylvan, it is much more explicit in The Tournament of Thorns but still not risen to the level of an openly queer relationship, as in How Are the Mighty Fallen (1974). But the queer attraction is almost entirely one-sided (of John for Stephen) and Stephen’s affection for John is always heavily sublimated to a strong homosocial friendship, as that of two brothers. And as with Lady of the Bees, where Swann creates brief jealous tension between Sylvan and Mellonia, here John is jealous of both Miriam and Ruth for the attention they get from Stephen. This jealousy is only resolved at the end.

The majority of Part II concerns the journey of Stephen, John, and Ruth south toward London, through the thick woods of central England (Robin Hood territory). They don’t seek out Mandrakes this time but they are accosted by them nonetheless, captured, and taken prisoner to an underground cavern where they are to be roasted and eaten. Here, we discover that the Mandrakes speak Old English and have a hard time understanding Stephen and John (and vice versa). We also learn that the Mandrakes have adopted Christianity from the early proselytes who converted the Celtic peoples of Britain in the centuries after the Roman Empire withdrew from the Isles. It is possible to surmise that the Mandrakes see their actions against the humans as a kind of crusade. But to Stephen and John they are merely savage monsters. They are rescued from their captivity by Ruth, who was conveniently bathing in a river when Stephen and John were taken, and Ruth manages to free the boys by trading their lives for a crucifix in her possession. John, however, doesn’t believe that such savage beings would so easily let their enemies leave, and begins to grow ever more suspicious about Ruth’s true nature, while Stephen sees this as further proof of her angelhood.

Part III sees the trio flee from the woods and arrive at the Manor of Roses, a grand feudal estate maintained by Lady Mary after the death of her husband in the Third Crusade (1189–1192). Lady Mary is the ideal mother figure, having lost her own son to the Children’s Crusade when he was somewhere near the ages of John and Stephen; she also looks (and smells) like John’s recently deceased mother. In Lady Mary John finds a willing surrogate mother, and in John Lady Mary finds a new son. She takes in this ragtag trio, feeds and clothes them, but also is also suspicious of Ruth. When Lady Mary and John accuse Ruth of being a Mandrake, she proves her humanity by cutting her hand to the bone with a Saracen sword brought back from crusade. Ruth reveals how she ran away from her uncle, a feudal lord, who tried to sexually assault her (and stole the crucifix, traded above, in the process), and how she embraced Stephen’s idea that she was an angel in order to escape with Stephen and John south to London. With this revelation, Stephen admits he probably always knew she was human but needed to believe in the fantasy in order to force himself to escape the drudgery and oppression of being a Saxon villein in Norman England. Stephen and Ruth decide to leave together for London, but John wishes to stay with his new surrogate mother. In a final twist, after Stephen and Ruth have gone, Lady Mary is approached by an aged female Mandrake at the edge of her estate, who reveals that Lady Mary is her daughter and was always a Mandrake. Embracing this shocking truth, Lady Mary sends John off to crusade with Stephen and Ruth, and in the parting sentences invites the Mandrakes to come live with her in the Manor of Roses. “Earth, the mother of roses, has many children” (167).

In the end, The Tournament of Thorns is a less assured book in the quality of its craft, control of its subject matter, and shape of its narrative. But it is no less interesting, especially for the way it variously contends and extends themes present elsewhere in Swann’s work. It is particularly evident that the novel is a fix-up, since the three parts feel quite disjointed from one another; there is a single narrative across them, and Swann gives us Lady Mary’s first-person narration as a frame (though it drops away for most of the novel; this worked much better in the shorter 1966 novella), but the progression across the parts does not feel naturally integrated. For one, Miriam is confusingly and unnecessarily killed between parts one and two; her presence in part one ends up feeling epiphenomenal to the novel as a whole. Moreover, the action of each part, while being tenuously connected to the violence committed by and against the Mandrakes, feels disconnected from the action of others, almost as though they are three separate vignettes about Mandrakes, and not an overarching narrative about Stephen and John and whomever is accompanying them that part. It all feels a bit discombobulated, though it reads quickly and easily, and Stephen and John (and especially Ruth and Lady Mary, to say nothing of Miriam) emerge less as characters and more as set pieces—which is definitely not true of Lady of the Bees, where, even when narrative focus on a character is limited (say, Celer or Amulius), the sense of them is indeed quite strong. It’s hard to forget, say, Mellonia or Remus; easy to forget John, Stephen, and especially Ruth and Miriam.

Swann’s story—that is, this whole business of the Mandrakes and of crusades in high-medieval England—worked better as the novella “Manor of Roses” than as the fixed-up The Tournament of Thorns. Part I is largely incidental to the novel qua novel, except to establish Stephen’s hate for the Mandrakes, an unnecessary addition to the plot of “Manor of Roses,” which turns more on the suspense of the three characters travelling together, getting jumped by the Mandrakes, and coming across Lady Mary’s manor. The emphasis in the novella is thus much more squarely on Lady Mary’s turning out to be a Mandrake. The contents of “The Stalking Trees” novella only add a further example of a Mandrake child (Rebecca) and the death of Stephen’s parents by the Mandrakes; neither incidents are necessary to move the plot forward, nor do they serve to either further humanize the Mandrakes nor to further monsterize them (there is the scene where Stephen and John are sickened by hunters killing a Mandrake baby, but the moral uneasiness of this is not developed further, unfortunately). And, as noted, the inclusion of Miriam into the novel’s full narrative becomes quite awkward; she has to be killed off between Parts I and II because she doesn’t fit with Swann using Ruth’s sudden appearance and seeming angelhood to convince Stephen of his need to go on crusade (it’s not a particularly convincing plot device anyhow, so could have been jettisoned to incorporate Miriam instead of Ruth). What’s more, the fact that Part I includes the discovery of a unicorn—a whole glade of unicorns!—and that this has a profound effect on Stephen in particular is essentially abandoned in Parts II and III, making it both significant (at least, to Part I) and completely irrelevant to the larger novel.

Mandrake Horror and Crusade Fantasy

The Mandrakes of The Tournament of Thorns are unique among Swann’s other fantasy beings, in large part because they are not the prehuman people of the ancient and primordial past, as the Dryads, Fauns, Centaurs, Tritons, Minikins, Minotaurs, and others were, but are instead presented as largely vicious, savage monsters who feed on humans. They are figures of horror, of dark forests and dank dens; they are the warning children need not to wander into the woods at night, rather than the rare beings of yore one would be lucky to encounter. (And to be sure, Swann delivers on the scenes of dread and horror; he really missed a calling as a horror writer!) The Mandrakes are, in this way, contrasted against the unicorns (who are almost completely forgotten after part one) and are described as a menace that has been progressively growing across central and southern England, invading from the north.

Perhaps, as I noted above, the Mandrakes are not as removed from the main of Swann’s fiction as it would first appear. True, The Tournament of Thorns is much less sympathetic to the Mandrakes than any of Swann’s other novels are toward their non-human beings, where any ill-treatment by humans is presented as a tragedy against nature, as inherently wrong. The Mandrakes are presented rather clearly as monstrous, they are invaders, and they are invoked by Stephen as an enemy worthy of crusade. But despite this framing of the Mandrakes as a barely intelligible monstrous enemy, the sympathetic, kind embodiment of motherhood—Lady Mary—is revealed to be a Mandrake, just as innocent Rebecca was. There is, then, some sense in Swann’s novel that because the narrative is told from the perspective of those who know only to hate the Mandrakes, the novel can only frame them as monsters.

To be clear, the narrative voice in The Tournament of Thorns is a bit muddled. It is presented as a retelling of Stephen’s (especially Part I) and John’s (especially Part II) stories from the perspective of Lady Mary, who appears briefly in a short prologue setting up the boys’ narrative as akin to the tragedy of the Children’s Crusade and returns at the beginning of Part III to narrate the conclusion. In theory, the narrative then is first person, with the third person portions being Lady Mary’s recounting of Stephen’s and John’s perspectives, as told to her that evening in her manor, but the narratives in Part I and II are so deeply personal—for example, relating John’s inner thoughts about his homosocial desire for Stephen—that it seems unlikely they would actually be known to Lady Mary. But whatever the slippage in narrative voice, all three perspective characters have reason to fear and dislike, even hate, the Mandrakes. This is unlike most of Swann’s novels of the prehumans, which have prehuman narrators (e.g. Lady of the Bees offered first-person perspectives from a Dryad and a Faun).

In the end, though, we learn that we have gotten a Mandrake’s perspective, though filtered through Lady Mary’s belief that she is human (and all the attendant fears about Mandrakes this entails). The revelation is initially a moment of sincere horror for Lady Mary; when she is told by her Mandrake mother what she is, she responds with revulsion: “I flung my hands to my ears as if I had heard a Mandrake shrie[k] in the night. It was I who had shrieked. I fled… I fled…” (164–165; ellipses in original; the text gives “shrief” instead of shriek, but I believe this is a typo, as there are several in the novel). But, after a moment of reflection, during which she worries over potentially hurting John, and consequently urges him to leave with Stephen and Ruth, Lady Mary embraces her revealed identity, goes to the woods to pray at one of the crosses she believes the Mandrakes erected “like a bulwark […] to thwart whatever of evil, griffins, wolves, men, might threaten my house” (167), and invites them to live with her: “Help me. You and your friends. Share with me” (168). Lady Mary still believes herself a danger to John, since Mandrakes can drain blood by touch, and perhaps doesn’t want to scare John with a revelation that might shake his confidence in her status as surrogate mother, but she also doesn’t shirk her newly revealed identity. Though she initially flees from it, she welcomes it in the end.

I think we might read this ending as acknowledging that the Mandrakes are only the object of human terror and fear because they have been made that way, both literally driven to monstrosity and also created as monsters in human myths and folk beliefs. Put another way, the violence of human civilization—the very thrust of Swann’s prehuman stories: humans destroying the grand, ancient people, who embody magic and love and wisdom, and who were here first—has run ragged over whatever the Mandrakes once were, leaving them little choice but to shrink into the shadows, to become the monsters humans imagined them to be, just to survive. The Tournament of Thorns, then, would seem to ask what becomes of the Forest Folk (nearly 3000 years after Lady of the Bees) when they have forgotten who they were and have been driven to savagery by humans.

This question of savagery, invoked throughout The Tournament of Thorns is also underscored in Swann’s narrative use of the crusades and all that they imply. The crusades, for anyone unfamiliar (and, if so, uhm… what?), were, most simply, a series of Western Christian invasions of non-Christian lands between the eleventh and fourteenth centuries. They were invasions by Christian soldiers against both pagans in Eastern Europe, especially the Baltics, and against Muslim (and sometimes Jews and Eastern Orthodox Christians) in the Balkans and the Levant. The initial goal of crusading was to recapture Jerusalem from the Muslims, but also, after the crusaders had gained a foothold in the Levant, to protect the newly established Crusader States (sometimes called Outremer, from French outre-mer, “overseas,” and still the French term for their colonial territories), and, especially in the Baltics, to convert pagans to Christianity. The crusades have been read as an early example of the ideology and tactics of colonial expansion that would follow from Europe in the early modern period. While scholars have intensely debated this, literary historians are much clearer about how the cultural imagination of the crusades in medieval Western Europe, particularly the presentation of a violent, binary opposition between Christians and non-Christians (i.e. Saracens, originally a term for all non-Christians, but which increasingly referred specifically to Muslims) in popular medieval romance, paved the way for later understandings of race that emerged in the early modern period and were solidified into racist, racial hierarchies by the Enlightenment.

Drawing on the work of medievalists and her own insightful readings, Maria Sachiko Cecire in Re-Enchanted: The Rise of Children’s Fantasy Literature in the Twentieth Century (193–204) argues that the figure of the Saracen—the dark, monstrous other figured in so much medieval romance, especially in the chanson de geste tradition concerned with Charlemagne—in Western European literature offers one historicizable origin point for what Ebony Elizabeth Thomas in The Dark Fantastic: Race and the Imagination from Harry Potter to the Hunger Games calls the “Dark Other,” the (often racialized) looming threat of darkness over light, evil against good, orc versus elf, alien contra human that structures the narratives and worlds of so much sff. Cecire’s argument is deeply historicized with numerous examples from medieval literature, draws on recent research by medievalists and early modernists about the (complex and multiple) origins of race and racial hierarchies in the West, and connects these to the literary practices of writers like J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis, as well as to later fantasists (positively and negatively) influenced by them, such as Susan Cooper, Philip Pullman, and Tamora Pierce. While Cecire only skims the surface of fantasy fiction’s engagement with fantasy imaginaries of the Middle East and Muslims, I think the specific figuration of the Saracen within the larger frame of the white, western views of the Dark Other stands. As Tanvir Ahmed so insightfully shows in an essay for Strange Horizons, such depictions are widespread in twentieth and twenty-first century sff.

The hazy idea of the Saracen outlined by Cecire is thick in the atmosphere of The Tournament of Thorns. Saracens are an object of obsession for Stephen, who wants more than anything to be a crusader, though as John points out several times, Stephen knows very little about Christian doctrine and is not interested in crusading for any explicitly religious reason. Instead, Stephen sees himself as a new Alexander: he wants to lift himself up from poverty, servitude, and obscurity by testing his manhood in battle, preferably through adventures in far off places. He connects this idea of heroic masculinity to some vague and culturally powerful idea of crusading against a “bad guy,” the Saracens who captured Jerusalem and defeated the Third Crusade. For Stephen, then, the Saracens are most definitely some vague figure of the (racialized) Dark Other, and they become occasionally grafted in Stephen’s binary imagination of good guys and bad guys to the monstrous figures of the Mandrakes. John, too, uses the language of the medieval Dark Other, calling one of his Mandrake captors “Bloody Saracen!” (118). But Saracens also loom large over the story generally, not just in Stephen’s drive toward self-fulfillment: the narrative regularly (and often clumsily) refers to Saracens to create world-building texture. One chapter opens with the observation that “the sun was a Saracen shield in the sky—Saladin’s shield, a Crusader would have said” (105). There’s little rhyme or reason for this observation (which only makes sense if you know what a sipar shield is) except to remind readers, as often as possible, that the crusades—and the enemy of crusade—permeate the cultural world of the characters.

That the crusades are central to The Tournament of Thorns is obvious. They are both a fact of high-medieval life, as Swann renders it (one of his two primary sources was Henry Treece’s The Crusades (1962)), but also a subject of critique and an opportunity to reflect on the ideologies of Christianity and masculinity at work in Swann’s medievalist fantasy. Indeed, the novel opens with Lady Mary denouncing the crusades and the ideology behind it:

It was eleven years ago, in the year 1202 of Our Lord, that my husband’s comrade-in-arms […] rode to me with news of my husband’s death and, for the grieving widow, the riches captured before he had died in battle. Captured? Pillaged, I should say, in the sack of Constantinople. You see, it is a time when men are boys, rapacious and cruel, as ready to kill a Jew, a Hungarian, a Greek as an Infidel; when men are happy so long as they wield a sword and claim to serve God—Crusading it is called. (3–4)

When describing how the childish impulse of crusading, of using religion to justify violence and greed, resulted in the Children’s Crusade that killed her own son, Lady Mary calls the “Crusader’s code” “an evil demon of pox [that] also possesses children” (4). Later, she calls crusading and the Children’s Crusade specifically a trick of the Devil to get back at God, distorting Christianity into the very image of evil. It is this very “evil demon of pox” that infects Stephen; he needs to believe an angel (Ruth) is guiding him in order to start him on his journey, but he feels compelled to crusade nonetheless. And he wants to do so for much the same reasons Lady Mary decries as exemplifying the sense that “it is a time when men are boys,” “happy so long as they wield a sword and claim to serve God”: he wants to be great, to play the hero.

Swann is elsewhere critical of Christianity as the ideology that has led to the crusades. For example, when John and Stephen are captured by the Mandrakes and discover that they are Christian, and that Ruth used this knowledge to trade their freedom for her crucifix, he thinks inwardly: “Her story troubled him. He had heard of many Christians who failed to keep promises; Crusaders, for example, with Greeks or Saracens” (123). Moreover, the knights of Baron Ralph’s castle, many of whom have been crusading, as well as a knight encountered in their travels, are all depicted as decidedly not chivalric, as hyper-masculinity assholes. Or, put another way, if knights are chivalrous, and if chivalry is a Christian ideal, both chivalry and the Christianity behind it are depicted as crude, undesirable, untrustworthy—masculine (derogatory). In Lady Mary’s supremely motherly words: these “men are boys.”

Furthering this critique of Christianity, John reverses the imagery that aligns the Mandrakes with Saracens (which he invoked just pages before), when describing how the Mandrakes look at Ruth’s crucifix:

[…] the Mandrakes gazed on such a rarity as they had never seen with their poor sunken eyes or fancied in their dim vegetable brains. In some pathetic, childlike way, they must have resembled men of the First Crusade who took Jerusalem from the Seljuk Turks and gazed, for the first time, at the Holy Sepulchre; whatever ignoble motives had led them to Outre-Mer, they were purged for that one transcendent moment of pride and avarice and poised between reverence and exaltation. It was the same with the Mandrakes. (120–121)

Here, the Mandrakes in all their monstrous, vegetable inhumanity are imagined as the ignoble crusaders who, on actually seeing something holy, temporarily, “for that one transcendent moment,” put aside all that has corrupted them. The suggestion, of course, is that such a moment is fleeting; the pride and avarice are otherwise all-consuming, they are the baseline ideology of crusading. And, depicted in this way, the crusade is as monstrous as the Mandrakes are to John.

Swann’s The Tournament of Thorns plays, in a somewhat sordid and complicated way, with the medievalist notion of the Saracen as the Dark Other of fantasy that descends from the depiction of (often monstrous) non-Christian others in medieval romance. Swann seems to suggest that the cultural formation that engendered the Christian/Saracen opposition in medieval Western European discourse—the crusades—is part of the tragedy of Western Christian civilization, just as the destruction of the prehuman peoples by the rise of human civilizations (i.e. the wellspring of our idea of the West) across the ancient Mediterranean were a tragedy. Swann achieves this critique through his direct presentation of the crusades as monstrous, as making monsters (and boys) of men, and through his comparison of crusaders to the narrative’s actual monsters, the Mandrakes. At the same time, the Mandrakes invoke both the Dark Other of medievalist fantasy and are, in some sense, humanized or “redeemed” from that Dark Othering. Lady Mary, as the ostensible narrator, as the main critical voice against the crusading ideology, and ultimately as a revealed Mandrake, serves as the linchpin around which the critique of crusade turns. If we read the final revelation and her embrace of her Mandrake nature and kin as overturning the portrayal of the Mandrakes as monstrous, then we are able to read her critiques of crusade as a critique from the perspective of the Dark Other.

Though I’m not altogether satisfied that this is an unproblematic reading of the narrative. After all, Lady Mary turns John away because she is worried of what being a Mandrake might do to him. This might be read as the implicit fear of the Dark Other being internalized: “I dropped my hands from his shoulders. I must not touch him. I must not kiss him” (166). Moreover, John and Stephen and Ruth set off together to London, and then perhaps to crusade. Lady Mary let them take her husband’s Saracen sword and suggests they should pawn it to fund their life in London; perhaps they will stay in London, but perhaps they will follow Stephen’s dream—Swann doesn’t give us an answer. But that they are headed off, theoretically, to crusade, and that they are essentially children, proves Lady Mary’s initial point that the crusades and their violence are essentially a childish dream, no better than Stephen’s vision of himself as the new Alexander. Perhaps such a dream is, to the individual who dreams it, a liberatory desire (isn’t that why Chosen One fantasies are so popular?), but it is fundamentally a dream that demands the destruction of the Dark Other and that requires men to embody cruel, violent masculinity.

I want to err on the side of reading The Tournament of Thorns in the more interesting, reparative light, especially since such a reading rhymes with Swann’s other novels, but I’m not wholly convinced yet. In the end, these essays of mine are starting places, provocations, not final words and endpoints.

The Tournament of Thorns …by Its Cover

A few words about the cover. And, really, I do mean a few, because the cover doesn’t give us much to talk about. The artist is not credited in the only version of this novel printed nor does ISFDB record who might have painted it. There is no obvious artist signature anywhere. Alas! The cover is nothing special, though it is beautiful and evocative in its own way. Most of the cover, unfortunately, is taken up with the author’s name and the novel’s title in huge, bold, red, white, and blue drop-shadow font, leaving really only the bottom third of the cover for visible art. This space features a unicorn sitting on the ground and wearing a collar, done in the style of the famous Hunt of the Unicorn tapestries; a castle soaring above some mountains in the distance (no such thing in the novel); and a blonde man in a purple robe holding a sword contemplatively while standing before a massive tree. I suppose the blonde guy could be Stephen, though I wouldn’t have pegged him as sporting a Prince Valiant-style haircut. And the giant tree (whose leaves take up the entire upper half of the cover painting) could be a nod to the foreboding, sun-stifling atmosphere of the forests where the Mandrakes lurk. The cover is unfortunately not much to write home about and has very little to interest the sff art critic, but it’s not objectionable either (except that font!).

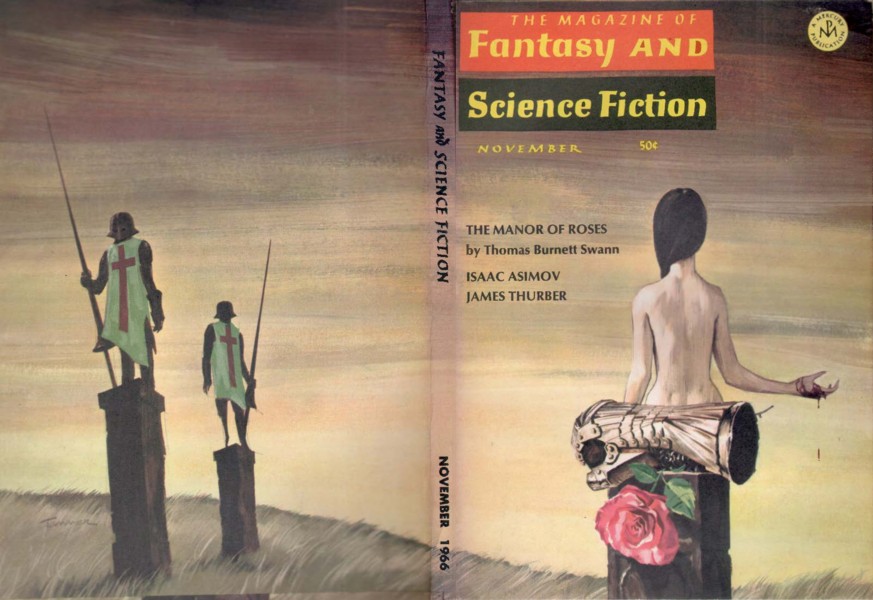

What is much more impressive, however, and a great note to end on, is the wraparound cover art for the Nov. 1966 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, which features Swann’s “Manor of Roses” as the cover story. The front of the magazine cover depicts the naked back of a woman, her right arm extended outward, with blood dripping from her hand. This is Ruth after she cuts her hand to prove her humanity. Her lower half is obscured by a stone pedestal atop which rests a gauntlet (?) and a single rose. It is a simple, stark, evocative, symbolic scene anchored in the background by a sky of dull yellows, browns, and greys, textured by rough brush strokes, and with equally dull, feathery grass rolling upwards in a slight hill to wrap around to the back cover. Here, on the slight incline of dreary grassland, are two pillars, each with a helmeted knight dressed in a Crusader’s surcoat (red cross on white) and holding a lance pointed at the sky. These possibly represent Stephen and John, the trio’s would-be crusaders. The three figures stand guard over a desolate landscape.

The art for this issue’s cover was done by Bert Tanner, who painted a number of covers for F&SF in the 1960s–1970s. His style is reminiscent of what you see quite often on sff novels of the 1960s and early 1970s, more impressionistic and symbolic than literal or realistic; it’s a style that, I think, often says very little about the novels themselves and which was popular precisely because of its ability to be slapped onto just about any book. But Tanner’s covers lean more toward the symbolic than the impressionistic and evoke a strong feelings of isolation, of sff worlds that are fundamentally unknowable to us, that are wholly estranging (and not in the Darko Suvin sense). Tanner’s cover art for “Manor of Roses” makes for a much more interesting emotional and symbolic frame for the story of Stephen, John, Ruth, and Lady Mary, capturing the nuance of the novel(la)’s critical view of crusade through its almost melancholic scene, its dull colors (the very opposite of the novel’s cover), and its sense of looming desolation.

To get notifications about new essays like this one sent directly to your inbox, consider subscribing to Genre Fantasies for free:

9 thoughts on “Reading “The Tournament of Thorns” by Thomas Burnett Swann”