Mistress of Mistresses by E.R. Eddison. 1935. Ballantine Books, Aug. 1967. Zimiamvia 1. [My version: First printing, Aug. 1967]

This essay is part of Ballantine Adult Fantasy: A Reading Series.

Table of Contents

Getting to Zimiamvia

Reading (and Struggling with) Mistress of Mistresses

Parting Thought

A narrative that is plodding and forgettable. Characters that are even duller. Exquisite prose that blandly philosophizes about beauty. In the main, a dry and uninteresting novel.

These were my reactions reading E.R. Eddison’s Mistress of Mistresses (1935), the first novel in his Zimiamvia trilogy, and the second chronological novel in my Ballantine Adult Fantasy: A Reading Series. It’s also the second Eddison novel I’ve read after last month’s The Worm Ouroboros positively surprised me and provoked over fifteen thousand words in my essay response, in large part because I found it a useful tool for thinking about fantasy fiction in the critical moment of its genre formation in the 1960s–1970s (even if that novel initially appeared four decades earlier). It was with piqued interest, then, that I took a big bite out of Mistress of Mistresses, only to spit it out and take a closer look at just what the hell I’d bitten into.

I freely (albeit disappointedly) admit that I found Mistress of Mistresses to be an incredible slog that I could only read a dozen or so pages at a time, and painfully so. This was a huge surprise to me, since while I wouldn’t say I loved The Worm Ouroboros, I flew through that novel’s 500-plus pages. There were plenty of moments in The Worm Ouroboros that I found less than compelling, largely because what I value and what Eddison values are diametrically opposed, but it was an engaging narrative and worthwhile literary experience nonetheless. The Worm Ouroboros had a brash, dastardly, pulpy feel to it, driven by its characters’ ridiculous derings-do, yet written in sophisticated, highly literary language, full of complex historical and literary allusions, and driven by a clear, well-wrought sense of critical purpose. Mistress of Mistresses does not lack for philosophical discourse or literariness—in many ways, the thirteen years between The Worm Ouroboros and Mistress of Mistresses allowed Eddison to grow into a finer writer, able to pen some of the most beautiful prose I’ve read; he graduated from the flat, bland sensuality of his first novel to the decadent flavors of beauty and desire that blanket this one—nor does it lack for political intrigue. But its whole is, as a novel, as a literary experience, —and I stress this next point—to me, quite dull.

To put it in the most cynical way possible, Mistress of Mistresses is a 393-page answer to the pressing, timeless question: What if the hottest woman you knew actually were Aphrodite—and what if she could be two women at once, one blonde and the other black-haired, one the ingénue, the other your own age and experienced in love? And what if you could be two dudes, equally awesome and lordly, and each of the two dude-yous could fuck one of the two Aphrodite avatars? That would be pretty cool, huh? And what if the takeaway were that beauty is the highest authority, the greatest power, and all women (and the best men) are prismatic reflections of elements of the one hottest woman imaginable?

This is a very reductive, pedestrian distillation of the novel, but that is pretty much what Eddison is after here, only he’s dressed it up in some of the finest prose imaginable: decadent, luxurious, evocative of seventeenth century plays with the flair of Greek, French, and Old Norse poetry tossed regularly tossed in, in their originals (usually with a translation given by one of the characters, but not always). You might imagine, then, that Mistress of Mistresses is very much the sexiest thing imaginable to an uptight Englishman (derogatory), especially one who, like Eddison, was more akin in spirit to a Victorian college don than an interwar civil service retiree.

To be fair, though, there are many who like Mistress of Mistresses and Eddison’s entire oeuvre (I’ve heard from some of you on Bluesky and I’m very glad for your insights and responses), as much and more than I liked The Worm Ouroboros (which, in the end, was quite a lot). If that’s you, I’m genuinely happy you exist and can engage with this novel in ways that I feel I can’t. The thing about being a literary critic and genre historian is, sometimes, you just really bounce off of something, even something many others like and find great value in, either personally or critically. And this was just such an unfortunate case for me (I’ll explain later a bit about why, for example, I find Eddison’s approach to aesthetics and beauty in this novel to be not worth my time.)

Despite my dislike, perhaps even disdain for this novel, I think readers and critics who are interested in anti-modernism and specifically twentieth-century revivals of decadence or aestheticism might find this novel worthwhile, since Mistress of Mistresses is clearly engaging in those mo(ve)ments. Someone with a great tolerance for late-Victorian aesthetic philosophy will likely find this book quite interesting; Pater is even mentioned in the “Overture.” And I know that there is good writing about this novel out there that has said useful and interesting things about it, even if the novel doesn’t critically interest me.

If you want an excellent analysis of Mistress of Mistresses by a literary scholar, I highly recommend Anna Vaninskaya’s Fantasies of Time and Death: Dunsany, Eddison, Tolkien (Palgrave, 2020). Vaninskaya is not only a great writer herself, but her readings of these three quintessential pre-genre early-twentieth-century fantasy authors are detailed, insightful, inventive, and convincing. Her chapters on Eddison really do a huge service to bringing Eddison more fully into fantasy scholarship—an important feat since he sort of circulates at the edges of the field and is little read today except by a few specialists and antiquarians (hi!). Her arguments are very specifically focused on how these authors theorize time and death, which is quite a niche consideration, but the monograph is the best kind of such writing since it makes the case for the broad importance of its topic to all scholars of these authors and of fantasy generally. In doing so, Vaninskaya convinced me there is something worthwhile in Mistress of Mistresses, if you bring the right set of questions to the novel. Still, I personally can’t bring myself to care about this novel enough to pose the right set of questions—from each according to their ability, to each according to their needs, might be an appropriate bastardization to explain my thinking here; I’ll leave Mistress of Mistresses to those who want to explore it more deeply—and so I am very glad for Vaninskaya’s work on Eddison.

Getting to Zimiamvia

I covered Eddison’s relevant background and how his books came to be at Ballantine in my earlier essay on The Worm Ouroboros. I don’t have anything to add here, except to expand on what I suggested in that essay: namely, that in their search for new books like Tolkien’s, Ballantine mistook Eddison’s first three fantastic novels (excluding 1926’s historical novel Styrbiorn the Strong) as a trilogy unto themselves, having likely read somewhere that Eddison had written a trilogy. And indeed he had, or partly: the Zimiamvia trilogy, composed of Mistress of Mistresses (1935), A Fish Dinner in Memison (1941), and The Mezentian Gate, the latter left unfinished at his death and published posthumously in several different editions since 1958 (Dell’s 1992 omnibus of the trilogy included drafts of chapters that were discovered after the first edition). I suggested in my earlier essay that Ballantine may simply not have known about The Mezentian Gate at first, since it had not yet been published in the U.S.; Ballantine’s April 1969 edition of that novel was its American debut and came more than a year after Ballantine’s editions of Eddison’s earlier novels, just a month before the BAF series proper began.

The back copy of Ballantine’s BAF preface edition of Mistress of Mistresses reads, “The second volume in the fantasy classic most often compared with J.R.R. Tolkien,” and goes on to describe the novel as “part of ‘The Worm’ group.” Further framing context is provided on the first inside page, which seeks to situate Mistress of Mistresses in the larger fantasy canon-making project Ballantine was pursuing:

The author of this extraordinary and reverberating book has dared to be completely imaginative, to brush aside the world, create and order his own cosmos, and with this background give us the death and transfiguration of a hero.

The scene is that fabled land of Zimiamvia (already mentioned in the previous volume, The Worm Ouroboros) […]. Here [heroes] forever live, love, do battle, and even for a space die again.

Lessingham—artist, poet, king of men, and lover of women—is dead. But from Aphrodite herself, Mistress of Mistresses, he has earned the promise both to live again in Zimiamvia and of her own perilous future favors.

This volume recounts the story of his first day in that strange Valhalla, where a lifetime is a day and where—among enemies, enchantments, guile, and triumph—that promise is fulfilled. (n.p.)

The language here is insightful, since it struggles to really assert what fantasy is, and why they’ve associated it with Tolkien, except that other critics (like James Branch Cabell, himself a later BAF author, quoted on the back cover) have said so, and that fantasy has something to do with daring “ to be completely imaginative” while creating and ordering one’s own cosmos as a background to a heroic tale. As Jamie Williamson, inThe Evolution of Modern Fantasy, has shown, these ideas about secondary world creation, imaginative literature, and heroic tales are constantly in (productive) tension in Ballantine’s, and especially Lin Carter’s, definition of “fantasy” in the BAF era. I said a great deal in the essay on The Worm Ouroboros about how it’s possible, I think, to see the glimmer of Eddison’s influence in later writers or, at the very least, how one can easily read Eddison’s fantasies against the more cynical, hero-driven stories of, say, sword and sorcery fiction (even if no direct influence can be claimed on some authors). Mistress of Mistresses is similar in this regard, but much less a heroic tale in the vein of The Worm Ouroboros, since it swings away from the crazy, bombastic adventures of Demon lords and more toward the realm of political intrigue shot through with dreamlike parlays with oreads, nymphs, dryads, ageless philosophers, and Aphrodite herself. In the most generous reading I can imagine, Mistress of Mistresses is something like the novelization of a lost fantastical tragedy from of the Jacobean era, serendipitously discovered by Eddison, and greatly expanded to include many scenes of philosophical introspection on matters of love, pleasure, and power that align with Eddison’s late-Victorian ideas about aesthetics.

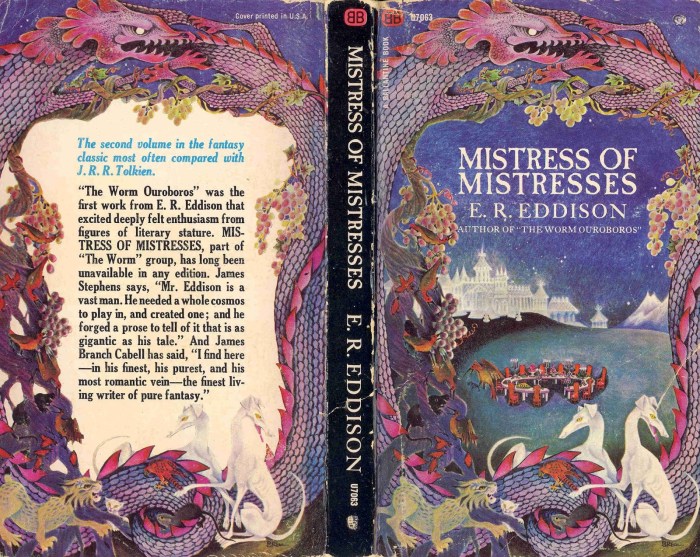

But before we get to the story itself, we cannot ignore the cover. I professed a great love for Barbara Remington’s art in my discussion of The Worm Ouroboros’s cover, even if that cover wasn’t anything particularly special. Remington’s cover of Mistress of Mistresses betrays a clear familiarity with the text, since it captures small details that really can only be got by a careful reader of the novel. The Mistress of Mistresses cover duplicates the ouroboros dragon motif of The Worm Ouroboros cover but changes the dragon’s colors, softening them to quieter shades of pink and purple that blend into one another. (All of Ballantine’s Eddison novels published in the preface to BAF use this motif, visually emphasizing the idea that these novels form part of a whole, “‘The Worm’ group.”) The dragon on the Mistress of Mistresses cover frames a field, at the center of which sits a round banquet table—likely the banquet at Ambremerine—and in the distance the glowing white facade of Duke Barganax’s palace of Acrozayana. Some mountains rise in the distance to the right, and the sky is dark, oceanic blue with a few pinpricks of starlight. More interesting are the figures around the frame-dragon: two greyhounds, recalling the villain Vicar’s hounds, one of whom (Pyewacket) has a sympathetic role in defending the hero Lessingham, and there are various other animals, including birds, a falcon, a rat (?), a lynx, and a white kitten. The white kitten is a pet of Queen Antiope and the lynx is a reference to Anthea (an oread who can take the form of a lynx—what is it with sff authors and sexy cat-people?!). Thick vines wind up the side of the frame-dragon, bearing grapes; notably, it is staring at the bubbles in wine that Lessingham has a sort of revelation that things may be a bit more otherworldly than they seem…

Remington’s cover for Mistress of Mistresses offers some memorable images, especially the greyhounds, the lynx, and the grapes, and the proliferation of odd details made me wonder how they’d show up in the novel. Remington was truly a gift to sff cover art and, to her immense credit, the promise of the novel created by her Mistress of Mistresses cover kept me going even when, after a few dozen pages, I could tell the novel would be a dreadful slog.

Reading (and Struggling with) Mistress of Mistresses

As noted, the Zimiamvia trilogy is set on the other side of the world (of Mercury) from the goings on in The Worm Ouroboros. It is glimpsed, at a distance, in that novel by the Demon lords in their adventure to Zora Rach Nam Psarrion to save Goldry Bluszco. They describe it as the place where the souls of heroes go to live on, either again or eternally—it is unclear. Where The Worm Ouroboros began with an “Induction” that spirited a contemporary Englishman, Lessingham, off to Mercury in a dream chariot, only to “dispense” with him some time later and focus on the secondary-world fantasy story (a major part of my discussion of that novel), Mistress of Mistresses begins with a much lengthier “Overture” that sees us at that same (?) Lessingham’s deathbed, on earth. Only, things are really weird. This overture is narrated by an unnamed man, younger than Lessingham, whom he befriended as a youth. If we assume this is the same Lessingham as in The Worm Ouroboros, then a lot has changed since he went to Mercury and saw the adventures of the Demons against the Witches. There are strange references to Lessingham having conquered Paraguay (6) and now king of the Lofoten archipelago in Norway, having apparently captured them and ruled them under anti-modern conditions; before he died, the government in Oslo was threatening to “take back their sovereign rights” over Lofoten and “reintroduce modern methods into the fisheries” (5, 5–6). The “Overture” takes place in the castle Lessingham built, presumably because this place reminded him of Demonland’s coast (5).

The unnamed narrator, who is called “a philosopher” (and so made me wonder, later, if he is Vandermast, the novel’s ancient philosopher figure and servant of Aphrodite on Zimiamvia) (8), is joined at Lessingham’s death-side by Señorita Aspasia del Rio Amargo, who is played up as the sexy dark-skinned, exotic Spaniard imagined by British men:“Her voice, low, smooth, luxurious, (as in Spanish women it should be, to fit their beauty, yet rarely is), seemed to balance on the air” (8; eight pages in and this novel is already way hornier than the 500 pages of The Worm Ouroboros.). These two friends of Lessingham—Mary Scarnside, his wife/lover from the “Induction” of The Worm Ouroboros died in an accident many years ago—mostly recount Lessingham’s theory of aesthetics (beauty and goodness are the ultimate reality, truth subservient to both, and goodness servant to beauty; see 15–16) and metaphysics (modernity is bad because it swallows up the individual, so a real man—“if they could but be men as this man” (17)—is one who creates conditions of non-modernity, say, by seeking the conditions of life outside the ordinary, in Paraguay or Lofoten or climbing mountains). Moreover, we learn that for Lessingham women represent that highest level of reality, beauty, and so are a key part of a real man’s search for individuality (it’s unclear how, but I imagine this is about heterosexual romance being the highest good a man can pursue). Hence, Lessingham, a man who since leaving his trip to Mercury has pursued a life that might get him into the hero’s afterlife in Zimiamvia. Or something like that.

As with The Worm Ouroboros’s “Induction,” Mistress of Mistress’s “Overture” is one of the more interesting aspects of the novel, but I also have no real interest in engaging the ideas Eddison puts forth here and which he extends, really, throughout the novel in trying to emphasize again and again that beauty, later described as pleasure, is the ultimate power in the universe. I find that sort of philosophy incredibly trite and uninteresting, if not verging on reactionary, especially in Eddison’s essentialist, reductionist vision of gender and his obsession, seen more clearly in The Worm Ouroboros, with great men doing great deeds (and which I found interesting but professed great disdain for), regardless of the morality of those deeds. And to be clear, I think aesthetics are incredibly important as a critical field of inquiry, but I find that Eddison is not a useful or interesting critic. He sets his characters up in a dinner party to discuss, for example, whether pleasure or power is greater, at length, and makes it from then on the key thematic concern of the novel (107–111). But he does nothing interesting with this theme and the depth of his understanding of aesthetics would seem to be a handful of ancient Greek sources and one reference to Pater that goes nowhere. It’s bland, turgid stuff.

Over Eddison, I much prefer the queer musings of Anne Rice’s Lestat, who breaks down our aesthetic desires, critiques them, refashions them, and shows them to be always changing, multiple, and complex in their play between divine and banal, erotic and chaste, and so on. I much prefer that to the dry obsession Eddison has here with the singular, transcendent, all-powerful beauty possessed by a particular kind of woman, who embodies the Sapphic (but notably very heterosexual) ideal of feminine beauty, the “Greek” ideal of Praxiteles’s nude statute, the Knidian Aphrodite, referenced several times in Mistress of Mistresses. Eddison’s ideas about beauty, though similar on the surface, have not the depth of Thomas Burnett Swann’s queer approach to beauty and his admiration for the feminine divine as a perfection of what is found, fleetingly, in the best of men—whom other men love. Eddison’s vision of beauty and all of his hundreds of pages philosophizing about aesthetics, amount, rather, to an incredibly dull vision of finding a woman so hot, with such nice, shapely, memorable feet (this is a plot point); such a fine, white, curving neck; such luscious, flowing hair (Barganax threatens to murder Fiorinda if she cuts her hair), that you just gotta admit she holds all the power. It would be kinky if it weren’t so patently, pathetically heterosexual in the most vanilla way possible. And yet it is all very beautifully written. And still yet it is all so exceedingly dull.

Now, I’ve gotten sidetracked a bit here from what exactly the novel is about. But, to be honest, it doesn’t really matter what happens, plotwise, in this novel because it’s all so damn boring and subsumed to the above concerns about aesthetics, beauty, and power. This is perhaps not fair to the novel, and there are those who quite enjoy the story itself (see Matthew David Surridge’s excellent retrospective on Eddison’s work in Black Gate). So I’ll summarize the main points.

After the “Overture,” Mistress of Mistresses kicks off with Lessingham—who may or may not be the same Lessingham from earth we have just been learning about—a noble lord in Zimiamvia, cousin to the cruel, ugly, thick-necked, hairy (hey, I’m just telling you what Eddison says!) Vicar Horius Parry of Rerek, in the middle of an impending crisis. Unlike The Worm Ouroboros’s Merucury, Zimiamvia is not split up into ethnic fantasy enclaves like Witchland, Demonland, and Goblinland, but is instead a more run-of-the-mill European fantasy world decades before that was an established trope of the not-yet-formed genre. The kingdom of Fingiswold, Meszria, and Rerek was recently ruled over by King Mezentius, who has died and left the throne to his youthful son Styllis. Many fear Duke Barganax of Meszria, Mezentius’s bastard son, older than Styllis, will try to claim the throne through rebellion. But before that can happen, king Styllis is secretly poisoned by Parry after Styllis, trusting his Vicar (not a religious role here, more like prime minister), signs a will claiming the Vicar should rule as regent until Styllis’s sister, Antiope, turns 21 (she’s almost 18). The will has some unclear wording which may or may not suggest that the powerful Duke Barganax should owe fealty to the Vicar. This legal unclarity leads to war.

Throughout this all, Lessingham is the Vicar’s man and is, oddly, loyal to him to a fault (I’ve seen it suggested that, by being loyal to the Vicar, he ensures he’ll have more messes to clean up, and thus more adventures, though I don’t buy this reading, since Lessingham despairs at the Vicar’s meddling with the alliances he builds). But despite his loyalty to a cruel man everyone hates, he is such a dashing, heroic man and is consequently admired by all (except Gabriel Flores). He builds peaceful alliances, smashes rebellions when those alliances fall apart, and brokers new alliances to hold together the three regions of the kingdom. This goes back and forth for some time until, with some legal wrangling to “prove” women can’t inherit the throne, Barganax declares himself king. At the same time, the kingdom’s enemy, Derxis of Akkama (who reads like an Arab- or Ottoman-inspired figure) takes advantage of this unrest, invades, and murders Queen Antiope, who has become Lessingham’s lover after she comes of age. With Antiope dead, no one has a claim to the throne greater than Barganax, so he becomes king. But the Vicar, unwilling to cede power, plots to make an alliance with Derxis and when discovered by Lessingham, has Lessingham killed in the middle of a crowd before Baraganx, and so is captured and killed himself. It is a tragic, stage-play ending and it’s easy to see in the back-and-forth political machinations a sort of theatrical flair inspired by Eddison’s love of seventeenth-century theatre.

Amidst all of this fantasy politicking (which has been compared to A Song of Ice and Fire, though Eddison doesn’t scratch the surface of what Martin accomplishes in even just a few chapters), Mistress of Mistresses spends most of its time with Lessingham and, to a lesser degree, Barganax, and especially their relationships with Queen Antiope and Fiorinda. This is a novel where characters are explicit mirrors or inverses of one another, or even parts of a whole—not only as a literary conceit but also as metaphysical fact of the storyworld. There is the running theme of pleasure and power, too, and Eddison maps these ideas to his principle characters: Lessingham and Antiope (power) and Barganax and Fiorinda (pleasure). Antiope is the blonde, Fiorinda the black-haired; Antiope the innocent lover, Fiorinda the experienced matron. Moreover, Eddison has the men be mirrors of the opposite woman: Lessingham sees in Barganax somewhat of Antiope, and in Lessingham Barganax sees somewhat of Fiorinda (this is, however, never queered!). Moreover, there are moments when Eddison makes this mirroring part of the narrative structure itself. There is, for example, a villa outside of time and space that Lessingham and Antiope access, a place they can go to secretly pursue their love. At the first such visit, Lessingham looks in a mirror, sees Barganax’s face, and the narrative shifts to Barganax, having just seen Lessingham’s face in the mirror, in that same villa but accompanied by Fiorinda, before continuing now with Barganax’s narration. It was, for me, the only truly interesting moment in the novel, a really transcendent scene where Eddison takes the promise of the weird dreamlike nature of the metaphysics of his story, and leans into it at a narratological level.

In the end, it is clear that Fiorinda is aware of everything that is happening, of all of the mirrorings between characters taking place metaphysically or metaphorically, and of Zimiamvia’s relationship to earth (whether as mirror, heaven, heightening of that world, is unclear). She is often found sitting with her nymph servants and with the philosopher Doctor Vandermast, musing obliquely about everything going on in the novel, who is a mirror/inverse/part of whom, what metaphysical games are afoot, and so on (again, rather dryly). The final chapter of the novel offers Fiorinda’s reflection on the narrative, as well as lengthy descriptions (yet again) of her beauty, her naked form, and a moment where she unleashes her full beauty which cannot be seen by man, because she is also Aphrodite herself, and therefore the highest power in the universe—all of existence is in service to Her (Eddison always capitalizes it, which makes me curious what he thinks about Christianity). Fiorinda might also be an incarnation of earth-Lessingham’s deceased wife, Lady Mary Scarnside (who makes an odd, psychedelic appearance in the novel when, for a moment, Eddison narrates some earth-events as though they are blending together with Zimamvia-Lessingham’s experiences (323–327)). Zimiamvia is, perhaps, then, a realm of Platonic ideals: heroes, beauties, cruelties. Though, to be honest, it’s a pretty pedestrian place as fantasy goes and, if Eddison’s goal was to present a fantasy world where everything and everyone are heightened qualities of people in our world, he succeeded far better in doing so with The Worm Ouroboros. Mistresses of Mistresses’s Zimiamvia is, by contrast, a plainer fantasy world, not at all what I expected.

Aside from the scene mentioned above in the pocket-universe villa, the one great joy of Mistress of Mistresses is its prose. It is not really as arcane in its style as The Worm Ouroboros. You could tell that Eddison was really trying out how the archaic prose worked in The Worm Ouroboros. That prose style is less evident in Mistress of Mistresses or, rather, it’s reduced to a background vibration, albeit one without which the texture of the narrative and the world of Zimiamvia could not be conjured into being. What has changed, though, is that Eddison is a much better prose stylist across the board, and he produces some of the most beautiful lines and description, everywhere underwritten by a sensuous texture that, in poignant moments, verges into the erotic—and, to be sure, this is a very horny novel. I want to quote a particularly favorite passage, to demonstrate some of the beauty of Eddison’s prose here, since it’s quite an accomplishment and worth lingering over. The passage is from Lessingham and Antiope’s first visit to Vandermast’s villa out-of-time, and is also an excellent example of how Eddison can evoke a completely entrancing, dreamlike, and weird fantasy world:

Lessingham felt himself sink into a great peace and rest. Strange and monstrous shapes, beginning now to throng that room, astonished no more in his mind. Hedgehogs in little coats he beheld as household servants busy to bear the dishes; leopards, foxes, lynxes, spider-monkeys, badgers, water-mice, walked and conversed or served the guests that sat at supper; seals, mild-eye, mustachioed, erect on their hind flippers and robed in silken gowns, brought upon silver chargers all kind of candied conserves, macaroons, fig-dates, sweet condiments, and delicate confections of spiceries; and here were butterfly ladies seen, stag-headed men, winged lions of Sumer, hamadryads and all the nymphish kindred of beck and marsh and woodland and frosty mountain solitude and the blue caves of ocean: naiad and dryad and oread, and Amphitrite’s brood with green hair sea-garlanded and combs in their hands fashioned from drowned treasure of gold. When a sphinx with dragon-fly wings sat down between the lights beyond Zenianthe [one of Antiope’s companions, herself a dryad] and looked on Lessingham out of lustreless stone eyes, he scarce noted her: when a siren opened her sea-green cloak and laid it aside, to sit bare to the waist and thence downward decently clothed in fish-scales, it seemed a thing of course; when a wyvern poured wine for him he acknowledged it with that unreflective ease that a man of nice breeding gives to his thanks to an ordinary cup-bearer. He drank; and the wine, remembering in its vintage much gold molten to redness in the grape’s inward parts, under the uprising, circling, and down-setting pomp of processional suns, drew itself, velvet-flanked, hot-mouthed with such memories, smoothly across his mind. And, so drawing, it crooned its lullaby to all doubts and double-facing thoughts: a lullaby which turned, as they dropped asleep, first to their passing-bell, then to their threnody, and at length, with their sinking into oblivion, to a new incongruency of pure music. (257–258)

On reading that again, and taking the time to write it out, it’s hard not to get caught up in the moment of it, to find oneself in that exquisite and wild room where impossible sights and beings are as the normal goings-on of a workaday life. Eddison’s writing is effective and affecting, conjuring scenes of pure brilliance, and so beautifully written that one can almost begin to understand why Eddison might be so obsessed with the idea of beauty and/as power—for so gracefully does he capture beauty. And he does so nearly everywhere in this novel, but especially in moments when he takes time to develop an extended, one-off metaphor to capture a feeling, extending that in time and on the page so that it starts to become real. Taken for example this, from later in the same chapter quoted above:

Sometimes so in deep summer will a sudden air from a lime-tree in flower lift the false changing curtain, and show again, for a brief moment, in unalterable present, some mountain top, some lamp-lighted porch, some lakeside mooring-place, some love-bed, where time, transubstantiate, towers to the eternities. (273)

Here, Eddison captures a feeling, a sense, a smell, and how these together evoke memories; it is a hyper-specific description but so crystalline in their clarity that I feel I know exactly what he means: the scent of the lime-tree—which I’ve never smelled before—blowing on the wind lifting the curtain and space and time, pulling me through the pages, brings me back to where I have never been, to memories I’ve never had, and ensconces me in their eternity, but just for a moment. Eddison uses these vivid, elongated descriptors, which draw so obviously on a wealth of personal experience, throughout the novel. They are beautiful, lush, evocative. They almost make me like this novel, as a whole, for love of these passages individually, for their art. Almost; craft is only part of the whole.

Parting Thought

I wouldn’t say that these are my last words on Mistress of Mistresses. I have the whole rest of my life ahead of me to (re)think about the novel, and perhaps my thoughts will change. Just the other night I rewatched Logan’s Run (1976), formerly what I thought was one of my favorite sff movies, but this time walked away convinced that it’s actually a pretty shitty movie at every level (except design, which hits it out of the park). Who knows, maybe some years from now I’ll read something that convinces me Mistress of Mistresses is worth another try, and maybe I’ll love it then. And maybe—probably, I’ll venture—not.

But I wouldn’t dissuade anyone from reading Mistress of Mistresses; you may very well find everything you’re looking for in it.

Here’s hoping the next novel in this reading series, Eddison’s A Fish Dinner in Memison, is of a different nature.

To get notifications about new essays like this one sent directly to your inbox, consider subscribing to Genre Fantasies for free:

8 thoughts on “Ballantine Adult Fantasy: Reading “Mistress of Mistresses” by E.R. Eddison (Zimiamvia 1)”