A Fish Dinner in Memison by E.R. Eddison. 1941. Ballantine Books, Feb. 1968. Zimiamvia 2. [My version: First printing, Feb. 1968]

This essay is part of Ballantine Adult Fantasy: A Reading Series.

I rather dreaded A Fish Dinner in Memison after finishing Mistress of Mistresses—easily one of the dullest, most plodding, and driest novels I’ve read in… my life? (I’d rather read every Richard Knaak novel than read Mistress of Mistresses again.) Thankfully, A Fish Dinner in Memison, published six years after the previous novel, was a decidedly less drab novel than its predecessor. It ticks along, not unlike The Worm Ouroboros, and is slightly more interesting for having a clearer vision of its philosophical purpose and certainly of its politics, which Eddison lays more plainly—and concerningly—bare, and for playing with narrative space and time as Eddison jumps back and forth between Zimiamvia and early-twentieth-century England and Europe with gleeful regularity.

But A Fish Dinner in Memison is not an excessive improvement over Mistress of Mistresses, it is merely a smaller and better seasoned portion of the same meal. I would not like to read it again nor would I gladly recommend it to others, but I did find it more accessible as a critic (perhaps here’s where my critical weakness with regard to Eddison is showing; one could accuse me, I suppose, of just not “getting” Mistress of Mistresses and I will admit to finding Eddison’s philosophical investments frankly boring). So, yes, A Fish Dinner in Memison gave me more to chew on. But a meatier dish is not a better dish for having a few more spoonfuls of beef than broth, if the meat is rancid.

A Fish Dinner in Memison is a step back in time (insofar as time is a stable thing in the Zimiamvia trilogy) to events that transpire before Mistress of Mistresses. In brief, it narrates two stories—one on earth, one on Zimiamvia—that intertwine. For Eddison, earth and its characters are the creation and but one instance of the infinite possibilities of the divinities who call Zimiamvia home, and all is subservient to Her and Her manifestations in other women.

On earth, we follow the courtship and marriage of Edward Lessingham and Mary Scarnside over the first few decades of the twentieth century. These are the same Lessingham and Mary from the “Induction” of The Worm Ouroboros; or, if not the same, they are some mirror or shadow or other instance of those characters (in the nineteen years between these two novels, Eddison has come to write both characters very differently, so it’s hard to aver whether they are intended to be the same but Eddison himself has changed them, or if they are simply different characters who represent Eddison’s philosophical belief that all things are but infinite representations of two truths: the divine She and He). The novel ends with the death of Mary and with Lessingham’s subsequent fall into deep depression, which radically changes his beliefs about souls/beings persisting beyond death, leading him to become the eccentric conqueror hinted at in the opening of Mistress of Mistresses.

On Zimiamvia, we are in the final days of King Mezentius’s life (he is dead in Mistress of Mistresses, leading to that novel’s succession crisis) and very little happens, plotwise. Perhaps the only significant development is the “first” meeting of Duke Barganax and Fiorinda, though their dynamic is no more interesting and just as incredibly dull as it was in Mistress of Mistresses. However, there is also a truly wonderful scene—one of few in this novel—where Mezentius confronts Vicar Horius Parry (antagonist of Mistress of Mistresses) just as Parry is planning a coup, forcing the Vicar to turn on his fellow would-be-regiciders. Eddison’s dialogue here is crisp, cutting, full of foreboding and atmosphere, and is (fittingly) nigh Shakespearean. But it’s a fleeting moment of real narrative showmanship for the novel. Most of the Zimiamvian scenes and chapters are given over to characters lounging about and discoursing on philosophy, with three full chapters toward the end detailing the eponymous fish dinner. Eddison liberally intercuts scenes between earth and Zimiamvia, expertly weaving them together so that events on earth are reflections of events in Zimiamvia, and earth events are given greater meaning by contrast to or comparison with the characters of Zimiamvia and their philosophical discussions (which often play out, in practice, on earth).

Odd as it might sound, especially as the namesake for a novel, the fish dinner on Zimiamvia hosted by Duchess Amalie, mother of Barganax and mistress of Mezentius, is consequential to Eddison’s entire literary project. At this dinner, Mezentius (Zeus) and Fiorinda (Aphrodite)—the other principal characters being shades of their divine He (Barganax, Lessingham) and She (Amalie, Mary)—discuss the creation of a separate world as a philosophical thought experiment, deciding what it should ideally be like, how beings in this world should act, what they should value, and what the purpose of such creation would be. And because Mezentius/Zeus and Fiorinda/Aphrodite are in fact the divine beings who control the universe, Anna Vaninskaya in Fantasies of Time and Death: Dunsany, Eddison, Tolkien (Palgrave, 2020) describes this scene of creation at the fish dinner as actually creating the narrative world of “earth” as it is written in both Mistress of Mistresses and A Fish Dinner in Memison. I either missed that that was the case—in fact, I don’t recognize the world Fiorinda wishes created as being descriptive of our earth or the earth of the narrative (though this could be my disdain for or misunderstanding of Eddison’s philosophy)—or Vaninskaya is making a critical leap based on her greater familiarity with the text. Vaninskaya is an incredibly canny reader of Eddison’s novels and their philosophical intertexts (really, it’s quite astounding!), so I lean toward her interpretation while straining every so slightly to reconcile it with my reading. (If, like me, you quite dislike Eddison’s Zimiamvia novels, Vaninskaya is great at exploring what could be interesting about them.)

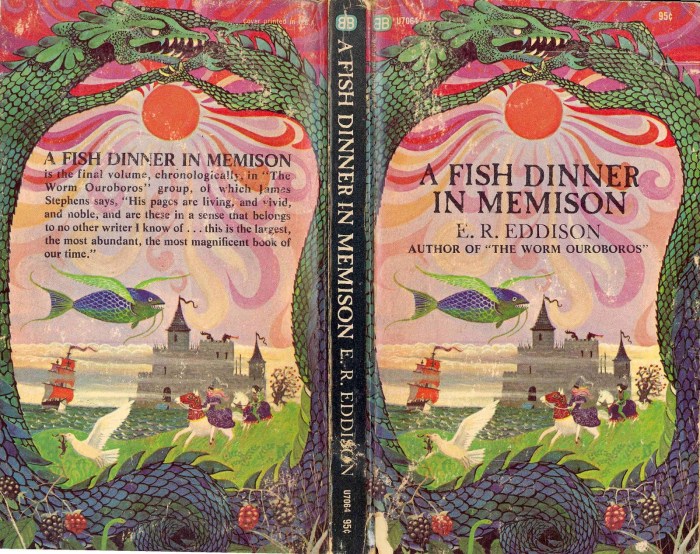

I’ve surmised previously that, in the wake of Tolkien’s famous trilogy (and I know people insist on calling it “actually just one novel split into a trilogy,” per Tolkien, but such has publishing created a trend!), Ballantine considered The Worm Ouroboros, Mistress of Mistresses, and A Fish Dinner in Memison if not a cohesive trilogy then at least some shared story. Cover copy variously described all three books as entrants in a “vast fantasy,” “the fantasy classic,” or “‘The Worm’ group.” Here, Ballantine’s mass market back-cover copy describes A Fish Dinner in Memison as “the final volume, chronologically, in ‘The Worm Ouroboros’ group,” which is simply not correct but gives further credence to the idea that Ballantine didn’t yet know about The Mezentian Gate. It might have made more sense for Ballantine to refer to it as the “Lessingham group,” since Lessingham, in some small fashion, is about all that holds these three novels together. But I can see how one might read A Fish Dinner in Memison as an “end” to the story of… whatever the hell Ballantine thought Eddison was doing with these books, since it traces rather neatly the romance of Lessingham and Mary as the central gravity around the novels might be said to orbit. (One could, retroactively, read The Worm Ouroboros more fully into the governing logic of the Lessingham/Mary romance, and Eddison’s idea of eternal love evidenced by them as instances of the divine She and He, though I’m not sure how compelling that reading of his first novel would be and even Vaninskaya doesn’t venture there.)

One way I’ve come to think of Eddison’s Zimiamvia novels over the past few months of slow, torturous progress through them is as a kind of theory-fiction. That is, as a literary space where “the opposition of theory and fiction” dissolves, each melding with and creating new meaning for the other. This is especially evident in A Fish Dinner in Memison, much more so than Mistress of Mistresses and explicitly very different from The Worm Ouroboros. Each of these novels, read in chronological order (1922, 1935, 1941), is progressively more difficult to read against the later terrain of fantasy fiction that Ballantine placed them into as the genre form was concretizing in the 1960s–1970s. Each is seemingly less concerned with the fantasy world itself, with the narratives of heroes and magic that would come to be (problematically) definitive of fantasy in Lin Carter’s exegetical project both through the volumes published in the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series and in his critical work about fantasy published in and around the series. A Fish Dinner in Memison thus emerges in Eddison’s oeuvre and in fantasy’s developing history as a thoroughly meta-fantastic meditation on narrative and worldbuilding, which Eddison yokes to his particular philosophical interests in a Spinozan sense of the divine (sub specie aeternitatis), a Nietzschean sense of ethics, a Machievellian sense of power, and his own sense of gender and sexuality.

With regard to the latter, and which I explored somewhat in the essay on Mistress of Mistresses, Eddison is nonetheless deeply heterosexual. He makes clear that the masculine is subservient to the feminine and yet still retains all the hallmarks of a patriarchal vision of women and femininity. Here, the feminine is powerful because it’s desirable to (heterosexual) men; because, in his vision of things, all men want to serve a woman with a shapely figure—and Eddison is very clear about what he likes: he is an ass man, giving lengthy descriptions whenever possible of just how arousing are women’s “carriages.” To be fair, Eddison is strikingly good at capturing eroticism, in large part because he is an incredibly talented author whose prose, I’ve suggested before, is easily at home with the late-Victorian Aesthetics movements. Yet this eroticism, particularly the way Eddison frames desire as a form of power, giving as evidence Lessingham’s or Barganax’s desire for Mary or Fiorinda as the principal (and correct) driver of ethics—what She wants is definitionally Good—, is deeply problematic. Fucked up, even. Eddison eschews any other idea of justice or equity, completely sidesteps them, to argue that the only thing that matters is service to Her. Thus is love good and eternal, because it serves Her. And because all beings are merely temporary instantiations of the infinite possible varieties of He and She, the hardships of life and its injustices are simply irrelevant in the larger scheme of things. For this reason, it’s easy to see why Tolkien thought of Eddison’s work as arrogant and cruel—and I am increasingly inclined to agree.

And to be clear, I’m not just drawing this out of the text and inferring from characters’ dialogue or actions what Eddison’s ethical and political visions are—even if Eddison is one of those authors whose characters really do seem to say what he’s thinking; there is little distance, here, between author and character, which is part of his larger philosophical claim about all things being sub specie aeternitatis: all things are instances of the One Thing, eternity or god or divinity: He and She. These philosophical investments are clearly stated by Eddison himself in the “Letter of Introduction” which takes the place of the “Induction” of The Worm Ouroboros and the “Overture” of Mistress of Mistresses. Unlike the earlier novels’ narrative prefaces, the “Introduction” to A Fish Dinner in Memison is an actual letter explaining the novel’s philosophy, written to George Rostrevor Hamilton, a colleague of Eddison’s, a civil servant like him, a WWI poet, and a noted literary critic. Over thirteen pages, Eddison lays out his theory of divinity, Truth, and Goodness. It reads like the work of someone who just discovered a few key texts in philosophy and wants to write his own grand unifying theory of the world: it’s so simple! Do what hot chicks say! It offers a dismal, hyper-individualist, and selfish ethical and political message, but the “Introduction” underscores just how clearly by 1941 Eddison viewed his literary work as an attempt to manifest his schoolboy philosophy.

Thankfully, there are whip-smart critics like Vaninskaya who are willing to take Eddison’s journey, indulge him, and draw out how his philosophical investments fit with the work of the thinkers he drew on. But for me, Eddison’s interests veer heavily and indulgently toward topics I find plainly boring, such as the nature of divinity, time, and death, or our purpose in life—yes, all major animating questions for many philosophers, but just so uninteresting to me!—, and his answers to most of those tedious questions return to his conviction of divinity, and of ethics that flow from that belief, that I find off-putting and grossly conservative. Eddison’s ethics, such as they are plainly laid out in A Fish Dinner in Memison, and his politics, as I’ve traced in the previous two essays on The Worm Ouroboros and Mistress of Mistresses, are repugnant. He is a beautiful writer and a regressive thinker.

As fantasy, too, A Fish Dinner in Memison does very little for me, and as theory-fiction I find it marginally more interesting but largely uncompelling. Even as a conservative work, it’s rather dull compared to, say, Tolkien’s complex dialectic between radical and conservative thought, or, hell, that of the libertarian sf writers of the postwar period, such as H. Beam Piper, Larry Niven, or Jerry Pournelle—all repugnant in their own ways, but significantly more interesting for me to work with critically than Eddison. The most generous thing I can say about A Fish Dinner in Memison is that, hey, he really did the thing. He clarified his philosophy, he brought it plainly to bear in his fantasy world, and he very effectively made the points he wanted to make. To be more generous than I’m wont, and to turn to someone who is more sympathetic to Eddison’s novels: as Anna Vaninskaya has shown, A Fish Dinner in Memison is a rich novel for those interested in Eddison’s philosophical intertexts and his elaboration of a very particular ethical vision of the world. How you get on with that, though, will really determine whether A Fish Dinner in Memison and probably the Zimiamvia trilogy as a whole is for you.

Finally, to try to gesture at the novel’s place in this larger project of reading through the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series, I should say that Eddison’s A Fish Dinner in Memison certainly holds critical value as a historical work that by virtue of its prefacing the Ballantine Adult Fantasy project has been canonized into the history of the genre. In that regard, it’s a great example of how philosophy (especially ethics and politics), narrative, and worldbuilding are inextricable in ways that so many authors—most with only a fraction of Eddison’s literary talent—take for granted. The novel is also a stark reminder to fantasy critics to do the work of reading fantasy at and across all three levels, to look at how philosophy, narrative, and worldbuilding interact and inform one another, how they create and/or resolve tensions, and how they read against a novel’s larger literary and cultural contexts. That’s not a stunning revelation (which probably suggests my general uninterest in the novel), but rarely does a fantasy novel make so clear the interplay between these elements and suggest to critics a renewed diligence to the complexity fantasy can afford.

For now, though, I’m exhausted with Eddison and look forward to a long reprieve consisting of novels by Mervyn Peake, David Lindsay, and Peter Beagle, and even some of Lin Carter’s nonfiction, before returning to Zimiamvia with The Mezentian Gate and there ending the “preface” novels and diving into the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series proper!

To get notifications about new essays like this one sent directly to your inbox, consider subscribing to Genre Fantasies for free:

9 thoughts on “Ballantine Adult Fantasy: Reading “A Fish Dinner in Memison” by E.R. Eddison (Zimiamvia 2)”