Titus Groan by Mervyn Peake. 1946. Ballantine Books, Oct. 1968. [My version: Fifth printing, Jan. 1974]

This essay is part of Ballantine Adult Fantasy: A Reading Series.

Table of Contents

Mervyn Peake and the Road to Ballantine

Reading Titus Groan

Ritual, Power, and the Weight of History

Keda and the End of All Things

Parting Thought

Mervyn Peake’s Titus Groan, the first novel in his Gormenghast series, is a strange, lengthy tome at turns comedic, melancholic, and Gothic—and utterly suffused with a sense of wonder at the sprawling yet claustrophobic world of Gormenghast castle and its surrounds. Peake’s Gormenghast books have been variously described as Gothic, social satire, and, of course, fantasy (though its labelling as fantasy has vexed many who seek a simple, singular definition for the genre), inheriting a literary legacy as diverse as Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy (1759–1767), Anne Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794), and William Morris’s The Wood Beyond the World (1894) and The Well at World’s End (1896) (these latter two were included in the BAF series), and blending that legacy with the anarchist sensibilities of the late modernist literary movements Peake belonged to.

The Gormenghast trilogy, sometimes called the Titus trilogy, sprawls across three novels that run to 543 (Titus Groan, 1946), 568 (Gormenghast, 1950), and 284 (Titus Alone, 1959) pages in the Ballantine editions, making the trilogy lengthwise a good comparison with Tolkien and Eddison’s works. More novels were intended to continue Titus Groan’s journey into the wider world beyond Gormenghast, with the series expected to unfold across multiple volumes, but it was cut short when Peake died in 1968 at 57. His widow, Maeve Gilmore, worked on a fourth novel, Titus Awakes, based on fragments left by Peake, but it was only released in 2010 and was based on two different manuscripts left by GIlmore after her death in 1983.

The most apt gloss I have of what it is like to read Titus Groan is that it is Downton Abbey through a funhouse mirror. It is a novel about social hierarchy, about calcified institutions of power, about the umbrageous weight of ritual and noble bloodlines receding into a past so far distant that neither the purpose nor value of the order of things can be remembered. And yet, as Titus Groan begins to show, just as Downton Abbey documents across its several seasons and films (though in a thoroughly different manner and tone): what has been might not always be. The personages of Gormenghast are those of the Abbey seen through John Carpenter’s They Live sunglasses and distorted by the kaleidoscopic density of Peake’s anti-authoritarian critique. Yet, for all that, the inhabitants of Gormenghast are rendered—if humorously, satirically—as deeply human subjects of a system of power, domination, and authority that they simultaneously (and exuberantly!) maintain and are dehumanized by. It is all they know; it is all Gormenghast has known for nigh 1,500 years.

But Titus Groan records a change beginning, a spark of something different glowing faintly at first in the stonework bowels of a castle whose outrageous bulk spreads a mile in every direction, and the facade of more than a millennia of stultifying Groan rule and ritual begins to crack up.

Mervyn Peake and the Road to Ballantine

The Gormenghast trilogy is lauded by just about everyone in the sff world whose inclinations and tastes lean a bit more toward the literary. It is something of a hallmark of a writer’s deep and intelligent familiarity with fantasy’s history to reference Peake as an influence. From Michael Moorcock (a close friend of Peake) to Neil Gaiman (acknowledgement) to China Miéville, Peake is considered a writer’s writer, often contrasted to Tolkien, who is for the masses (this has to do mostly with Tolkien’s influence on fantasy generally, which is seen, unfairly, to both Tolkien and later writers as leading to repetitive slop; and also has something to do with political readings that view his works as conservative and/or reactionary). The Gormenghast trilogy is also included in just about every “best of fantasy” list (an honor also accorded to Tolkien, but rarely to Eddison), both those produced by/for the literati and those by/for more general audiences, and the novels have remained regularly in print, with a new edition appearing every decade or so. They’re the kind of books a reader can obsess about and, as Premee Mohamed recently remarked, the series seems at once universally beloved yet oddly obscure.

Mervyn Peake (1911–1968) was a British writer born in Guling, China to missionary parents who relocated with their son to England in 1922. Peake was a talented painter and illustrator and was commissioned during the final years of WWII to draw scenes of the war after suffering a nervous breakdown in 1941–1942 while serving in the Royal Artillery regiment. (These direct experiences of the atrocities of both Nazism, including the death camps, and of war itself, have led some critics to read the Gormenghast series’s narrative about the arch-individualist character Steerpike as an allegory for Hitler and destructive authoritarianism.) Peake illustrated numerous novels, including a new edition of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, and he wrote poetry as part of the late modernist New Apocalypse and post-surrealist movements. Peake was in poor health due to early-onset dementia (with Lewy bodies, which manifests Parkinson’s-like symptoms) throughout the later 1950s until his death in 1968. He was left unable to draw and write for much of that period, so that Titus Alone, his final Gormenghast book, saw heavy intervention from his editors at Eyre & Spottiswoode, so much so that the text was inconsistent with the previous books, leading New Worlds editor Langdon Jones to produce a new edition in 1970 more in line with the earlier texts and Peake’s notes.

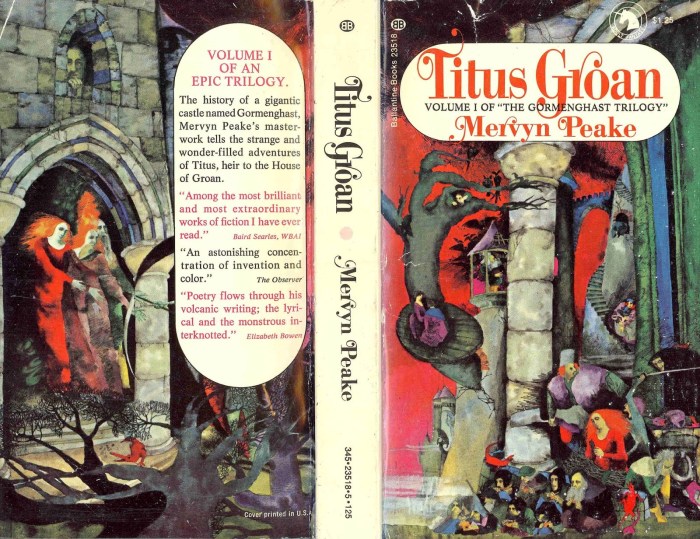

Peake’s Gormenghast trilogy, published toward the end of his life and overlapping with his deteriorating health, is his greatest legacy. All three novels were (re)published by Ballantine as part of their effort to build up a fantasy frontlist—and therefore a semi-coherent understanding of “fantasy” as a mass market genre—in October 1968, a month before Peake’s death. The Ballantine mass market paperback editions of Titus Groan, Gormenghast, and Titus Alone marked the first time Peake’s novels saw American distribution and are no doubt responsible for his legacy in fantasy today. They were released with vibrant, strange—and, to me, very unlikeable albeit totally apt—wraparound covers painted by Bob Pepper, who did a number of BAF covers in the following years. On the Titus Groan cover, the grey, green, and blue hues of Gormenghast’s inconceivable stoney mass predominate,, while the inhabitants of the castle are rendered as haunting, blobby things garbed in reds and purples; the sky is blood red. It is an ugly, off-putting cover that captures the equally ugly, estranging nature of the novel’s world, where everything is at once familiar and grossly distorted.

The Ballantine editions of the three Gormenghast novels were released individually and as a boxed set and the covers explicitly number each volume as I, II, and III “of ‘The Gormenghast Trilogy’,” with the back cover of Titus Groan stating “Volume I of an epic trilogy.” The novels bear different blurbs from an array of mainstream literary and sf publications and personages, and the first volume includes a brief description of the series:

The history of a gigantic castle named Gormenghast, Mervyn Peake’s masterwork tells the strange and wonder-filled adventures of Titus, heir to the House of Groan.

Emphasizing the series’s locus in a castle and being about wonder-filled adventures, Ballantine’s copy sought to anchor it in direct relationship to Tolkien and Eddison fantastical, adventurous series while remaining aloof from the specifics: is it a medieval castle? Are the adventures a kind of quest? Is it a trilogy in the way that Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings is? What’s with the strange scene on the front cover? The women on the back cover gesturing at a tiny, dragon-like creature? Why is there a tree growing out of the castle wall?!

Set alongside Tolkien and Eddison, Peake sits slightly further afield from the other two in terms of how they inhabit fantasy as a generic form—both Tolkien and Eddison having pre-modern secondary(-ish, in the case of Eddison) worlds with magic, mythical creatures, and gigantic battles, though they are radically distinct from one another in tone and philosophy—but Peake is no less unique, inventive, or artistically inspired than Tolkien and Eddison. Indeed, kicking off Ballantine’s fantasy canonizing project with these three authors, all products of the early twentieth century, but informed by different interests, experiences, beliefs, and politics, makes for a compelling case that even in its early phase of genre formation, through Ballantine’s retrospective canonizing project, fantasy was always diverse and multiple, not easily contained by singular definitions and sets of expectations. And with David Lindsy and Peter S. Beagle to follow in the next few months, the genre was looking pretty damn capacious by the time BAF officially launched under Lin Carter’s editorship in May 1969. By the time the BAF series wrapped up in spring of 1974, Ballantine’s Gormenghast editions had gone through five printings. Not a massive number, and I have no idea of the size of Ballantine’s print runs for the series, but the sales demonstrate a consistent demand for and interest in Peake’s work as both damn good literature and as foundational, in some way or another, to what fantasy was shaping up to be in the mid-1970s.

As I’ve laid out in previous discussions of fantasy’s prehistory leading up to BAF—that is, the literary history BAF gleefully plundered in creating a canon for modern, “adult” fantasy—there are two major strains of the genealogy of fantasy coming out of the Victorian period and the early 1900s (to say nothing of the older stuff, which has its own histories) and merging together retroactively in the late 1960s/early 1970s as a market genre trying to make sense of its predecessors while selling new things under this generic banner. These are the literary British tradition, associated especially with Tolkien and Eddison and William Morris and Lord Dunsany, and the pulp American tradition, associated with Robert E. Howard, Fritz Lieber, Poul Anderson, Fletcher Pratt, and L. Sprague de Camp. And yet there are outliers—of course there are! (This is history; is it ever so cut and dry?) Take for example, Beagle and Evangeline Walton and James Branch Cabell on the American side, standing out as particularly literary and not publishing in the pulps; or H. Rider Haggard and other imperial adventure fiction writers on the British side, having much more in common with (and indeed influencing) the American pulp writers than his British compatriots (though many have noted Haggard’s imprint on Tolkien).

The point is that while genealogies—lines of literary- and cultural-historical descent—are helpful to our understanding of how genres grow and change, they are not hard and fast rules, and need always to be given greater context and further nuance. Reading Peake into the history of fantasy further nuances the genealogy of fantasy’s market prehistory, since although his works easily fall into the literary strain of British fantasy (this is where Williamson puts him), he was a writer extraordinarily different to Tolkien and Eddison, but sharing much politically with the socialist Morris and with several others of his generation who did not get woven into BAF’s tapestry of fantasy (e.g. Henry Treece or John Cowper Powys). Peake was an active member of the late modernist New Romantics and New Apocalyptics movements in the 1940s; much of his poetry appeared in their publications and James Gifford has argued extensively in his important intervention in fantasy studies, A Modernist Fantasy: Modernism, Anarchism, and the Radical Fantastic (ELS Editions, 2018), that these movements and Peake himself were anti-authoritarian with anarchist sensibilities if not outright anarchist affiliation (a reading I’ll explore more in my piece on the second novel in the trilogy, Gormenghast). This strong union between late modernism, anarchism, and pre-genre fantasy rendered its own separate tradition of anti-authoritarian fantasy fiction that must be considered among the other genealogies (and will touch other BAF writers).

Even as we create narratives about fantasy’s history we have to continually revise them to account for genre’s capaciousness as a form, attending to how different texts, authors, editors, publishers, audiences, and sociohistorical contexts (read one way: material conditions) bring the genre into being.

Reading Titus Groan

For 1,474 years,[1] the family Groan has ruled (and been ruled by) Gormenghast and its “unspoken and iron-bound tradition[s]” (89). Until, that is, the coming of Titus Groan, born to be the 77th earl, and the appearance of a lowborn kitchen servant, Steerpike, who plots to raise himself to a higher social position. The sprawling novel that opens Peake’s Gormenghast trilogy begins on the day of Titus’s birth, and despite being named for him, we see the baby only a handful of times. The novel charts the life of the castle’s principal servants—Flay, the earl’s manservant; Swelter, the head chef; Doctor Prunesquallor, the Groans’ physician, and his sister Irma; Nannie Slagg, caretaker of Titus and Fuschia; Keda, Titus’s wet nurse; Sourdust, the Master of Ritual; Barquentine, Sourdust’s son and Master of Ritual following his father’s death; and Steerpike—and the living members of House Groan—the 76th earl, Lord Sepulchrave; his wife, Lady Gertrude; their daughter, Fuschia; and the earl’s identical twin sisters, Cora and Clarice—over the course of Titus’s first year in Gormenghast, and then some.

In the short period glimpsed across the novel’s 500-plus pages, the birth of Titus and the sudden rise of Steerpike catalyze a change in the claustrophobically static world of Gormenghast, leading to dramatic arson and Sourdust’s death, a deadly love triangle involving Keda and two men seeking her love, a murderous revenge plot between Swelter and Flay, the violent tossing of a cat leading to Flay’s dismissal from Gormenghast, and the earl’s eventual insanity and possible suicide by owl. All of this is narrated by Peake in lush atmospheric prose that meanders around the castle, bringing its dark halls, dusty attics, and ostentatious parlor rooms to strange life made all the stranger by the wild personalities who eke out a living here. Gertrude, for example, is accompanied everywhere by a herd of white cats and attended by a flock of birds that settle on her dress, her bed, all about her room. Doctor Prunesquallor laughs nervously every few seconds and his thoughts stray here and there. Nannie Slagg perpetually mishears whatever is said and interprets most conversation as a slight against her. Everyone is always talking past everyone else, intent on their own internal worries and schemes, as social confusions and misapprehensions seep through the social world of the castle. No one who calls Gormenghast home is normal; they are all vibrant social caricatures, very Britishly so, and the effect is of a demented Victorian social drama—a Dickens or a Trollope pushed just to the precipice of nonsense—playing out in the thoroughly Gothic environment of the castle.

The novel begins on the day of Titus’s birth and Peake takes us on a tour of the castle as the earl’s manservant, Flay, attends to various duties around Gormenghast. Flay starts the novel by announcing the heir’s birth to Rottcodd, caretaker of the sculptures kept in the Hall of Bright Carvings (more below), and then winds his way through the depths of the castle into the kitchen, where he picks up a hanger-on in the form of the reluctant kitchen servant Steerpike—a gangly, odd-looking boy with a protruding forehead and high shoulders (yes, everyone looks incredibly strange, too). The unlikely companions make their way to the living quarters of the earl and Steerpike is surreptitiously swept into the grand dramas of House Groan, overhearing secrets he shouldn’t (that Titus is an ugly baby) and getting access to rooms that are not meant for servants (like Lady Gertrude’s blue-carpeted Cat Room). Eventually, Flay drops out of the picture, forgetting Steerpike and unknowingly introducing him as a rogue element into the Groans’ lives as embarks on adventures across Gormenghast’s rooftop, discovering its myriad oddities and mapping the labyrinth of its forgotten nooks and crannies, familiarizing himself with the inhabitants he hopes to one day have rule over.

A great deal of the novel concerns Steerpike’s social adventures, climbing from kitchen servant to doctor’s assistant to eventual apprentice to the Master of Ritual and majordomo, of a sort, to twins Cora and Clarice Groan. He achieves this social rise through charm and a gift of the gab (the title of chapter 26, in which he endears himself to the Prunesquallors) that allows him to run intellectual circles around almost everyone he talks to, for the inhabitants of Gormenghast are represented as either dim-witted, emotionally immature, or mentally unwell. Steerpike, who comes inexplicably from nowhere and has no background beyond his discovery by Flay in the kitchen, seems preternaturally able to command people’s attention and loyalty, with the rare exception of Flay, who despises anyone seeking to curry favor with the earl and thereby displace his own position, and Lady Gertrude, whose only lucid moments in the novel, when she’s not lost in her obsessive relationship with her birds and cats, occur when she notices Steerpike’s sudden presence in the lives of the Groans and becomes suspicious.

Occasionally, Peake gives us glimpses of other lives, just enough so that we understand the stakes of Steerpike’s schemes. Special attention is given to the earl’s daughter Fuschia, a fifteen year old who is sullen, stubborn, and hungry for adventure, and behaves more like an eight year old. We also get a few chapters that familiarize us with the earl and his utterly melancholy nature, made all the more depressing by the oppressive burden of the nonsensical rituals he must perform as Lord Groan in order to satisfy the demands of his family’s lineage (more below). These characters, strange and unreal as they are—the kind of people one might expect are bred and raised in the isolating, loveless halls of, say, Windsor castle—, are rendered as deeply human by Peake, who turns a sensitive eye to what makes these characters familiar even when they are so grossly different. In particular, Peake goes to great lengths to emphasize the loneliness of Gormenghast’s inhabitants, how they seek love and affirmation, but how rarely they receive it or are able to recognize it when (rarely) given. It’s also worth noting that Ballantine included a number of Peake’s own illustrations of his characters, which are grotesque and strange, though I imagine they are of great interest to critics of British late modernist and post-surrealist art.

In addition to Peake’s wildly imaginative characters, Gormenghast itself is always at the forefront of the narrative. Indeed, the novel opens and closes with dramatic descriptions of the castle; at the beginning, Peake describes it thus:

Gormenghast, that is, the main massing of the original stone, taken by itself would have displayed a certain ponderous architectural quality were it possible to have ignored the circumfusion of those mean dwellings that swarmed like an epidemic around its outer walls. They sprawled over the sloping arch, each one half way over its neighbour until, held back by the castle ramparts, the innermost of these hovels laid hold on the great walls, clamping themselves thereto like limpets to a rock. These dwellings, by ancient law, were granted this chill intimacy with the stronghold that loomed above them. Over their irregular roofs would fall throughout the seasons, the shadows of time-eaten buttresses, of broken and lofty turrets, and, most enormous of all, the shadow of the Tower of Flints. This tower, patched unevenly with black ivy, arose like a mutilated finger from among the fists of knuckled masonry and pointed blasphemously at heaven. At night the owls made of it an echoing throat; by day it stood voiceless and cast its long shadow. (1)

Gormenghast is the first word of the novel, and clarification—“that is”—is immediately offered to further ground the reader, so that there is no doubt what Peake is talking about, even though we have no idea yet what Peake is talking about. But as the opening passage makes clear, operating in synecdoche for what the entire novel is ultimately concerned with, is that Gormenghast is a force against nature. A buttress against time, maintained by the family Groan and its rituals, Gormenghast stretches at least a mile across and is nestled at the foot of Gormenghast mountain alongside Gormenghast river. It predominates, it insists upon itself as much as on the natural world around it, and it insists upon you becoming as obsessed with it as everyone in the novel is. What we know of this world is entirely focused on the castle. We don’t know is how any of this works; whether, say, Gormenghast has great landholdings with a society of peasants providing for it, though we know from scant references that there are farms and that there are an innumerable number of nameless servants attending the castle and its few elite residents. We know also that this is not a medieval world, but one that seems decidedly modern, at least Victorian, in its technology and accoutrements; it is a world that has stuffed giraffes and celluloid and tropical fruits and pocket watches. Familiar, somewhat knowable, but decidedly other, defying logic and rational experience.

Ritual, Power, and the Weight of History

Perhaps the most remarked on aspect of Peake’s first two Gormenghast novels is the role and rule of ritual in the storyworld, the iron-clad laws that govern the day to day life of the castle, that structure its routines, give shape to its reality, and which are the constant duty of House Groan just as it is the duty of all others to serve the Groans so that they may perform, unimpeded, the rituals. The obscure and unintelligible rituals that circumscribe and license the strictly ordered social—and therefore political—world of Gormenghast are known only to the Master of Ritual, the ancient Sourdust and, after his death, his equally elderly son, Barquentine. These rituals require the attention of the earl to perform them several hours a day and they are all completely nonsensical. Much like spells or arcane knowledge in more familiar fantasy worlds, the rituals are recorded in a massive tome with yet another presenting alternatives should some element of the ritual require alteration (e.g. what to do for a ritual that requires a clear sky when it’s raining).

It has been widely acknowledged that Peake’s Gormenghast novels have (seemingly) no magic in them, even if they are clearly a kind of “immersive fantasy” in Farah Mendlesohn’s model. There is an article by Maggie White arguing that the presence of the green light throughout the novel represents a spiritual plane, but I’m not sure I agree; a more compelling argument lies in a disembodied voice Keda hears, which foretells immediate events (see below), though there Peake suggests that Dwellers believe too easily in the supernatural. However, Benjamin Robertson has neatly argued that the rituals of House Groan are themselves a kind of magic for the reality-supporting effects they have on the family Groan and the way that the rituals, by virtue of the sanctity of their maintenance, create a social/political world in which both the Groan lineage and therefore the rituals themselves must be maintained. As Robertson puts it,

the denizens of the castle have an absolute belief in these rituals. To be more precise, they concede the ritual in and of itself, regardless [of] whether they wish to take part in it. They may wish to escape ritual (as Titus does consciously in the second novel and as Selpuchrave seems to unconsciously in the first), but they never question the ritual at the level of ritual; in short, they never question that the ritual should be, only whether they wish to participate. And this, no matter how absurd the ritual.

And:

It is never clear why precisely such rituals take place. They are, as I suggest above, unquestionable (and hence Steerpike’s desire to command them and alter them for his personal gain, his desire for which is likewise unexplained except, perhaps, as a desire for power for its own sake). Barquentine, […] is shown to dismiss the living beings in the castle as transient figures and valorize the line of Groan. The “links” [individual earls] in the “chain” [the Groan lineage] are to him unimportant; it is the “chain” itself, the unending and seemingly without beginning legacy that must be maintained. Will some terrible fate befall the castle should the ritual remain un-performed? Does the ritual itself, as the impetus to the force of “something else,” drive the world of Gormenghast in a manner that is more than merely ritualistic, i.e. by virtue of some magic that derives from it, some appeasement of the gods, spirits, ghosts, demons, fairies, etc.?

It is a canny reading that emphasizes the way ritual operates as a kind of magic, albeit a thoroughly mundane version that fails to create wonder. Even Sourdust and Barquentine feel merely the tired pleasure of a job well done, while Sepulchrave lives a hollow, melancholic life reduced to the rote performance of these rituals. Ritual in Titus Groan is not a hand on the lever of power, but power itself, or rather its social/political instantiation in the world of Gormenghast. Not unlike Kafka’s “law,” it stretches back into time immemorial, having no known origin; lost are its meanings and purposes.

Ritual, power, and the weight of history are strong themes of the novel, interwoven as a critique of the social and political institutions that curtail life, maintain hierarchy, and ultimately deform us as people, reducing us to melancholy, insanity, apathy, or—worst yet—gleeful service of those in power. History has calcified Gormenghast and its hereditary rulership by the Groans into an unquestionable institution. It has its roles and its rules, inviolate and unchanging. When one worker dies (as Sourdust does) or is dismissed (as Flay is), they are easily, quickly, and remorselessly replaced. It is, quite simply, shocking to read this as anything but a radical critique of power and its accumulation by elites, not just in the immediate, but as a process of unchanging change—a facade before and behind which generations die in poverty, obscurity, and servitude (what Jameson might call “progress”). Not even the names of the Bright Carvers, the men whose carvings are selected each year by the earl to sit in the Hall of Bright Carvings, are remembered; and it is the duty of an obscure character—Rottcodd, who is so forgotten that he only learns of the novel’s tumultuous events at the very end, when he glimpses Titus’s earling procession from his high window—to do nothing but dust the anonymous carvings, day in and out, alone in a rarely visited room. Gormenghast’s rituals isolate and breed loneliness. They distort individuals into freaky caricatures of humanity, a process of dehumanization that Fuschia herself clocks as “beastly” (154; echoed earlier, 131, in a reference to the other inhabitants of Gormenghast as “beasts” for the way they behave toward one another), offering both an argument about the anatomizing experience of modernity and a critique of structures of power.

The connection between ritual and history runs deep through Titus Groan. Take, for example, the novel’s climactic event, when the observance of ritual is disrupted with catastrophic effects. This is the Burning of the Library, accomplished by scheming Steerpike and abetted in a very convoluted plot by the twins Cora and Clarice, who desire power, authority, and respect—and probably a good dose of normal human attention and love (another major theme of the novel and a countervailing force against power, as love is often disrupted/prevented by the Groans’ duty to ritual). The Library is Sepulchrave’s only respite from the oppressive weight of performing the rituals. Its burning, during the ritual planning of Titus’s first birthday breakfast, with all of the major characters inside, affords Steerpike the opportunity to look like a hero and save everyone from the fire he planned.

The Burning is intended to bring Steerpike into the social orbit of the earl, where he’ll have greater power, and it also gives him direct authority over the twins, whom he comes to control through manipulation, flattery, and faux-supernatural threats to reveal their complicity in the arson. The fire, however, has the unintended effect of killing Sourdust, potentially leaving a job opening for Steerpike to fill, and driving the already mentally unhealthy earl to insanity, as he comes to increasingly believe he is an owl, eventually committing suicide by giving himself as a meal to the owls in the Tower of Flint (or perhaps just disappearing; it’s unclear). But it’s not an unmitigated success for Steerpike, who hadn’t counted on Sourdust having an apprentice ready to take his place. Steerpike chides himself, reflecting on the redundant nature of Gormenghast that has kept it going through the centuries:

His power would have been multiplied a hundredfold; but he had not reckoned with the ancientry of the tenets that bound the anatomy of the place together. For every key position in the castle there was the apprentice, either the son or the student, bound to secrecy. Centuries of experience had seen to it that there should be no gap in the steady, intricate stream of immemorial behavior. (355)

And yet, with Barquentine replacing his father as Master of Ritual, he needs to train an apprentice to take his place, and chooses Steerpike. Meanwhile, with the earl dead (or simply gone—an event that has occurred only once before, when a previous earl disappeared), the baby Titus must assume the earldom. History churns ever into the present and “the ancientry of the tenets” of Gormenghast reconstitute themselves even in the wake of the tragedies of the Burning and the earl’s death/disappearance. But there is change working in secret, through Steerpike (and later Titus, in Gormenghast and Titus Alone). Steerpike is the epitome of the individualist who seeks power and authority, not for any clear purpose except to have it (he discourses half-heartedly to Fuschia on the need for “equality,” but it seems more like he’s trying to demonstrate his own cleverness than any sincerely held belief in equality). I’ll explore Steerpike more and the possibility of an anarchist reading of the series’s anti-authoritarianism in the essay on Gormenghast.

Though Rottcodd is an obscure character, only seen twice, he is both our entryway into and our envoi out of the novel. His present absence in Titus Groan and Peake’s use of him as a framing device for the novel—as one who is so devoted to service of the Groans and yet so completely invisible to them, easily glossed over in a year in the life of Gormenghast’s residents—allows us to see just how significant the changes wrought by Steerpike are. For Steerpike’s aberrant rise and the resulting early earling of Titus (see below) brings the castle to life and it is through the eyes of this obscure laborer, this devotee to the Groans and their rituals, this servant of the institution of Gormenghast, that we see the beginning of something new. Turning from his glimpse of the earling procession, he feels as though “everything had changed. Was this the hall that Rottcodd had known for so long? It was ominous” (541–542). A few lines later, Rottcodd notices:

Something, somewhere had been shattered—something heavy as a great globe and brittle like glass; and it had been shattered, for the air swam freely and the tense, aching weight of the emptiness with its insistent drumming had lifted. He had heard nothing but he knew that he was no longer alone. The castle had drawn breath. (542)

And a little later, Peake ends the novel as Rottcodd continues to experience the change, as history comes into the present, ritual broken, futurity and possibility on the cusp:

The castle was breathing, and far below the Hall of the Bright Carvings all that was Gormenghast revolved. After the emptiness it was like tumult through him; though he had heard no sound. And yet, by now, there would be doors flung open; there would be echoes in the passageways, and quick lights flickering along the walls.

Through honeycombs of stone would now be wandering the passions in their clay. There would be tears and there would be strange laughter. Fierce births and deaths beneath umbrageous ceilings. And dreams, and violence, and disenchantment.

And there shall be a flame-green daybreak soon. And love itself will cry for insurrection! For tomorrow is also a day—and Titus has entered his stronghold! (542–543)

It’s the kind of portentous ending that makes me go “whew, what the fuck?!” as I close the book and linger on its resonances with the events that sprawled across the novel’s year, unknown and mysterious to Rottcodd in his home in the Hall of Bright Carvings, but having brought so much change and promising more.

Keda and the End of All Things

There is a great deal in this novel that I haven’t covered here. Doing so would take thousands more words and it is really no surprise that, despite the paucity of Peake’s work in comparison to, say, Tolkien, Peake has prompted a great deal of scholarly attention, including a journal, Peake Studies, published between 1988 and 2015. Titus Groan alone is a rich text woven throughout with resonant themes of class, love, violence, loneliness, and knowledge. It is a book as mysterious as Gormenghast itself and it calls out for critical engagement as it breathes its first breath into the world Peake imagined. I’ve chosen to focus mostly in the above on the intertwining themes of ritual, power, and history, in large part because these will inform the discussion of Steerpike in my later essay on Gormenghast, and still so much more can be said about Titus Groan’s subtle and persistent articulation of these themes, but these short essays are just meant to start the critical exploration, to get the lay of the land. And still I can’t part with Titus Groan without commenting on the Mud Dwellers and especially on the mysterious figure of Keda.

The Mud Dwellers are introduced immediately at the novel’s start, their “mean dwellings that swarmed like an epidemic around [Gormenghast’s] Outer Walls” brought to attention with Peake’s first sentence as a contrast to the “ponderous architectural quality” of the main massing of the castle itself (1). Though the castle and its rituals rely on the labor and products of innumerable servants, none of which is hinted at in the novel except for a few scant mentions of farms lying within sight of the castle, only the Mud Dwellers and their strange labor offer a glimpse in Titus Groan at the relationship between the castle and anything beyond its walls. That labor, as I’ve described above, is the Bright Carvings, an annual ritual whereby three wooden carvings are chosen by the earl from among all those produced by the Mud Dwellers during the previous year, and those chosen works of art are “relegated” to Hall of Bright Carvings (2). Peake describes the labor of the carvers thus:

The competition among them to display the finest object of the year was bitter and rabid. Their sole passion was directed, once their days of love had guttered, on the production of this wooden sculpture, and among the muddle of huts at the foot of the Outer Wall, existed a score of creative craftsmen whose positions as leading carvers gave them pride of place among the shadows. (1–2)

There is no remuneration for the Dwellers’ labor, only the hope of “pride of place among the shadows” of the castle. In the course of the novel we learn little more about the Mud Dwellers and their lives, except that they are harsh, that youth and opportunities for romance are brief, that old age comes suddenly and quickly, that the Dwellers are sullen and stoic but capable of great passion, that the society is rigidly structured and the Bright Carvers (those whose works are chosen by the earl) are held in esteem as elites of the subaltern social hierarchy, and that the Dwellers are quick to punish social discretions, such as pregnancy out of wedlock.

Andrew H.S. Ng, in an article for Peake Studies, has read the relationship between the Dwellers and the castle as a sort of extractive colonial relationship between the colonized and colonizers. Ng’s focus on the language Peake uses to define the Dwellers—“mean,” “swarmed,” “epidemic,” sprawled,” “like limpets” (1)—is convincing and mirrors imperial disdain for the colonized subject, suggesting in Ng’s reading that in the castle’s view the Dwellers embody “baseness, abjection, uncontrollability, malignancy, disorganization, and vampirism” (29). And, indeed, Nannie Slagg’s brief venture into the Dwellings to find a wet nurse for Titus is filled with disgust at and fear of the Dwellers, a perfectly apt set of colonial attitudes. It is also the attitude of the powerful and the rich toward the powerless and the poor, and that this attitude is embodied by a servant of the Groans underscores just how corrupting the elitism of Gormenghast is (the talk of the difference between those of good “blood” and those of lower birth is constant among some inhabitants of the castle, particularly Cora and Clarice; though high-born, they cannot be earl, and so in their status as close to power without having it all, they constantly seek to denigrate those “below” them).

There are many ways, no doubt, to read the Mud Dwellers, and I have a hunch that, as an artist himself, Peake almost certainly meant for the relationship between the Dwellers and the Groans as a comment on the relationship between artist and patron in a capitalist economy where the labor of art is undervalued and the work of art, once owned by those with the means to acquire it, represents and enhances their wealth, status, and power. It’s a situation that forewarns of the grotesque high art trade today, where the outrageous wealth of lawless billionaires is converted into the high art-cum-commodities hidden by the thousands (if not millions) in impregnable, untaxed Swiss vaults: art reduced to pure capital, a relationship between object, status, and power maintained by institutions and rituals as inviolate as Gormenghast and its “iron-clad tradition” (89). It’s also possible to read the Mud Dwellers as the British subject in relation to the Crown, a relationship characterized in Peake’s day by high ritual and ostentatious displays of wealth meant to affirm power and social order. In having their carving chosen, or passed over, the Dwellers’ internal social order is affirmed and their subjection to the castle is renewed. Indeed, Adam Roberts, in an excellent essay on the trilogy, suggests several ways in which Gormenghast, like Tolkien’s work, is “about” England in the postwar period.

The Mud Dwellers are a critically rich element of Titus Groan’s narrative and storyworld and from their ranks Keda emerges into the novel for a brief time. Ng has referred to Keda’s narrative as a “paradox” and Pierre François in a chapter for Miracle Enough as a “mystery,” and Keda has no doubt provoked interest among many readers of Titus Groan even if she is easily lost in the novel’s sprawling mass of characterological convolutions, for her story sits almost entirely apart from the goings on of Gormenghast and unfolds across five short chapters: two are set in the Mud Dwellings (chs. 33 and 38) and three offer our only glimpse of a wider world beyond Gormenghast (chs. 49, 50, 51); the latter chapters also feels more like genre fantasy than anything else in the novel. Keda’s story is violent, too, with her lovers Rantel and Braigon murdering each other in ritual combat for her affection, and she is exiled from the Mud Dwellers to wander—now pregnant with Rantel’s child—the world beyond Gormenghast, but returns with a babe that, the end of the novel suggests, might herald great change…

Keda is chosen by Slagg as Titus’s wet nurse just after his birth; chosen because she has recently given birth to a baby who has since died. She is a widow of one of the Bright Carvers and once held status among the Dwellers but only by virtue of her husband. With him dead, her home is taken from her to be given to one of the other Bright Carvers (they are only men). When she returns from the castle, having fed Titus from her breast for long enough for him to be weaned to solids, she finds herself homeless. With her experience of both Gormenghast and life Outside, Keda is one of the few figures in the novel able to remark on the absolute weirdness of the castle and to characterize its atmosphere as oppressive. On returning to the Dwellings, she reflects:

This was the darkness she knew of. She breathed it in. It was the late autumn darkness of her memories. There was here no taint of those shadows which had oppressed her spirit within the walls of Gormenghast. Here, once again an Outer Dweller, she stretched her arms above her head in her liberation.

“I am free,” she said. “I am home again.” (246)

And yet, free as she is, relieved of the burden of Gormenghast and service to the Groans (however innocent and loveable a baby Titus is), she is homeless and without friends in the only place that feels like—and should be—home. She intends to turn to the two men who vie for her attention, both equally good options (the only difference is that one is quiet and sensitive, the other is passionate and fiery; it’s a real YA love triangle dilemma), and so she chooses the first she comes across, Rantel, leading to the death of both men and her exile.

As others have noted, Keda offers the only real window into sexuality in Titus Groan and the world of Gormenghast, which is elsewhere—that is, in the castle—entirely chaste (to be fair, this is itself a figuration of a certain sexual politics). Through Keda, we see the sweaty passions of the teeming masses (how else do they teem?) in stark contrast to the loveless world of Gormenghast, devoid of romantic interests, sexual desire, and even familial affection. (Steerpike’s flattery of Irma and the twins, and the clearly implied faux-Victorian restrained eroticism of their responses, is perhaps the only glimpse at desire among the castle’s inhabitant, and there we see a form of desire that figures eroticism as a tool for subjugation.) Beyond sexuality, Keda is also a figure at the intersection of class and gender in the world of Gormenghast, which clearly retains a strict patriarchy both within and outside the castle’s walls. Her ostensible impropriety in sleeping with Rantel, leading to his and Braigon’s deaths, and therefore the loss of two carvers who are important to the community, leads to her exile, and even before that her body is figured as both a failure of gender roles (her first baby having died) and a gendered tool for the social reproduction of the Groans’ power in the form of her providing milk for the newborn heir since his mother, Gertrude, has no interest in seeing the child.

Keda stands apart from the rest of the Titus Groan narrative, and one could easily see her story written out of the novel entirely, but her presence and her narrative’s oddness in context with the narrative of Steerpike’s scheming and the intra-class conflict between Flay and Swelter, and its sheer strangeness in an already strange novel, make it clear that Keda’s story is important to Peake and what he’s trying to do with/in Titus Groan. Importantly, among the novel’s large cast, only Keda comes from somewhere, has a personal history; only she reads as something more than a social caricature, as a human we might know and understand. Even Steerpike, the individualist extraordinaire who enacts significant change, has no background: he begins simply as someone who was serving in the kitchens. No more, no less. Before that? Peake doesn’t say and Steerpike has no interest in reflecting on his past. All that matters is where he is now and how he can manipulate circumstances and people to get somewhere else, somewhere better—to a place where he can exercise more power over others. Keda, by contrast, is anchored in her class position but not defined by its ostensibly fealty to the authority of the family Groan and the institutions of Gormenghast.

Her story ends mysteriously but is absolutely important to the arc of the novel and seems to hold the kernel that will change Gormenghast for good. In her final chapters, she wanders through the landscape beyond/around Gormenghast, now pregnant, and eventually—after hearing a guiding voice that may have been delirium or may have been the supernatural (“the reality of the supernatural was taken for granted among the Dwellers,” 375)—arrives at the hut of a hermit-like figure she calls the Brown Man (a name given him by the voice she “heard”) and later “Father” (not her actual father, but more as a social role representing the unconditional care and love so many in this novel lack). He feeds and cares for her and when she is near to giving birth he sends her back to the Mud Dwellings on horseback. Keda notes several times to the Brown Man that she will commit suicide after returning to the Dwellings and giving the baby to be raised where once she called home:

The[ Dwellers] will reject me—but I shall not mind, for still…still…my bird is singing—and in the graveyard of the outcasts I will have my reward—oh, Father—my reward, the deep, deep silence which they cannot break. (384, ellipses in original)

When Keda takes her leave, he declares:

No harm will come to you. You are beyond the power of harm. You will not hear their voices. You will bear your child, and when the time has come you will make an end of all things” (384)

Here, he speaks almost prophetically and acknowledges Keda’s desire to kill herself “with a rope, or with deep water, or a blade” (381) by noting “you will make an end of all things,” a phrase that can just as equally refer to something greater, beyond Keda’s own death, perhaps to the destruction of Gormenghast and its rituals and all it stands for—are these not the “all things” in focus throughout the novel?

Ultimately, we don’t know by the end of Titus Groan what Keda’s fate is. We know only that she returned to the Mud Dwellings and had her child, for at the earling ceremony, where Titus the baby must stand on a raft in the middle of a lake and hold some ceremonial objects, the Mud Dwellers appear at the edge of the lake to witness the his crowning. And with them is Keda’s child held in the arms of

a woman by the shore. She stood a little apart from the group. Her face was young and it was old: the structure youthful, the expression, broken by time—the bane of the Dwellers. In her arms was an infant with flesh like alabaster. (525)

Youthful but broken by time is how Keda is described elsewhere, just on the cusp of that moment in all Dweller women’s lives when their beauty is cracked by the agedness that takes Dwellers so quickly to their graves. But Keda’s name is not given; only the child is referred to as hers. And her presence and the baby’s presence here at the earling, at the end of the novel, is ominous, for when the one-year-old Titus takes agency for the first time and “decided to stand up” to complete the ritual acts expected of him (530), he also decides to rip off part of his ceremonial garb and throw it into the air, calling out with a “cry that for all its shrillness was unlike the voice of a child” (533). In response:

A tiny voice. In the absolute stillness it filled the universe—a cry like the single note of a bird. It floated over the water from the Dwellers, from where the woman stood apart from her kind; from the throat of the little child of Keda’s womb—the bastard babe, and Titus’s foster-sister, lambent with ghostlight. (533)

The novel then transitions to the final chapter, back to Rottcodd in the forgotten Hall of the Bright Carvings. Perhaps it is Keda, living as an outcast beyond her desire for death, to “make an end of all things.” It is, for sure, Keda’s child, and it is in the presence of this child, the bastard of an outcast from “the denizens of the Outer Wall—the forgotten people” (525), that Titus—his first life-giving milk bequeathed by Keda, her presence as his wet nurse required by the iron-clad power relations between the Groans and all others, but also by the need of a mother for a child—becomes earl. A moment from which great change will flow.

Such is the story of Keda, quietly and mysteriously ushered into the oppressive shadow of a much grander narrative, but in many ways, the story of Gormenghast is the story of Keda, as the story of all power and those who wield it is the story of those subjected to it.

Parting Thought

Titus Groan is an artfully crafted treasure that captures some of the freakiest weirdos driven to caricature by the utter madness of life “beneath the umbrageous ceilings” of the gargantuan mass of the never-dying castle Gormenghast (543). Titus Groan might be best understood as the exploration of a fantastical social world and the slow violence of ritual and power acting on Peake’s lively range of characters, who either go mad, succumb to violence (their own or others’), or try to gain power—which they mistake for freedom—as a way out from under the terrible weight of House Groan’s ancient, oppressive lineage, its endless history metaphorized and literalized by the castle itself. Titus Groan is fundamentally a novel about structures of power and how they distort life, and even so, it is a careful, caring rendering of those lives by a man who suffered and felt a great deal, and so it is suffused, yes, with loneliness but also with immense love and the desire to be loved. And so I have grown to care for it greatly in reading it and more so in writing about it.

Finishing the novel, reflecting on it, I now understand those friends on social media—when I complained about how dull much of the first, say, 350 pages are—who said to give the novel time. That it grows on you. That they didn’t like it at first either. I get it now. I incredibly appreciate this novel and look forward to the remainder of the series, especially Titus Alone, since it’s the novel folks seem to like the least for being so different from the first two. I can’t help but be contrarianly excited for that novel. And also perversely fascinated by the prospect of the “final” Gormenghast novel, Titus Awakes, which has only the faintest connection to Peake through his fragments, was written in two different manuscripts by his widow, was forgotten in a moth-eaten attic (how very much like Gormenghast, with Peake’s progeny searching through the remnants of the past like Fuschia in her own secret, inviolate attic that holds the discarded objects of Groan rule), and edited together to form a novel that, by all accounts, takes the world and narrative of Peake’s trilogy to weird new metafictional heights.

To get notifications about new essays like this one sent directly to your inbox, consider subscribing to Genre Fantasies for free:

Footnotes

[1] I get this figure from a scene in chapter 40, where earl Sepulchrave is performing a “biannual” ritual that has previously been performed 737 times (313). If we assume the usual meaning of biannual as twice a year, that means the ritual has been performed for 368.5 years. Not an awfully long time for a family on its 76th earl—a period so short that it would mean the average rule of an earl is fewer than five years. Doesn’t make a lot of sense. So I think we are supposed to read this as every two years (even though the word for that is biennial), meaning the ritual has been practiced for 1,474 years, giving us an average reign of closer to 19 years for each earl. Long, stable reigns, perhaps; but England has had 40ish monarchs since 1066, which is an average reign of over 23 years per monarch. This length of time would accord better with the sense of house Groan and the “iron-clad” law of its rituals stretching back into a past so distant that all meaning has been forgotten: the world is Gormenghast, for all its inhabitants and the denizens around it know, and all life is lived in service to the Groans. I prefer this reading, for this reason, but it’s entirely possible I’m wrong and/or Peake was just throwing in a number and not giving it too much weight (though that seems unlike a careful writer, but also very much like a surrealist, occasional nonsense writer…). Perhaps, too, this particular ritual is a later addition to the rituals of Groan, having only been performed for the last 368 years; or perhaps, in some forgotten past, earls of an earlier time neglected their duties… and so were forgotten. Who knows! Such is the mystery of Gormenghast.

I’m glad the ending talks about struggling with actually reading the bloody thing. It’s perhaps the ultimate example of a book I didn’t enjoy reading but enjoy having read.

I think we owe Lin Carter a vote of thanks for enshrining this work in fantasy’s canon so early (not that a lot of others haven’t reinforced it, or wouldn’t have done it) because you’re right about the plurality it gives to fantasy. In some ways, it almost feels like a New Wave spec fic exploration of society, just a generation before.

LikeLiked by 1 person

If anything, this Ballantine reading series has shown me that I really enjoy reading “bad” books and writing about them. And you’re right, it’s a hell of a struggle reading this fucking book — but worth it, I think!

As an aside, I don’t think the credit for Peake being with Ballantine goes to Lin Carter. The credit likely is Betty Ballantine’s. She was British and had good connections with British publishers, and moreover Peake’s publication predates Carter’s formal relation with Ballantine and the books really don’t fit Carter’s idea of fantasy. In Imaginary Worlds, Carter says he enjoyed Peake’s poetry “twenty years ago” when he was in college in the early 1950s, so I have no doubt he knew about the Gormenghast/Titus books, but I don’t know that the credit for Ballantine publishing them should go to him (he seems only ever to simply mention Peake, but not to stress his significance to the heroic fantasy tradition he’s interested in). Douglas Anderson makes some good points about keeping Betty’s influence front of mind when thinking about the series, as she likely restrained Carter’s curational tendencies.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, okay, that’s fascinating. I’ve only ever really read about the Ballantine Fantasy Series as Lin Carter’s passion project and never about the role of the Ballantines. Time to go educate myself. I have to admit, I did mildly wonder about the difference between Titus Groan and Lin Carter’s theory of fantasy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My essay on Carter’s non-fiction book, Tolkien: A Look Behind The Lord of the Rings, which is what brought him to the Ballantine’s attention, covers some of the background to their relationship. Carter did a lot of work with the intros to the volumes and no doubt selected a great many of the titles, but it was definitely a collaboration between him and Betty, in the end.

LikeLike