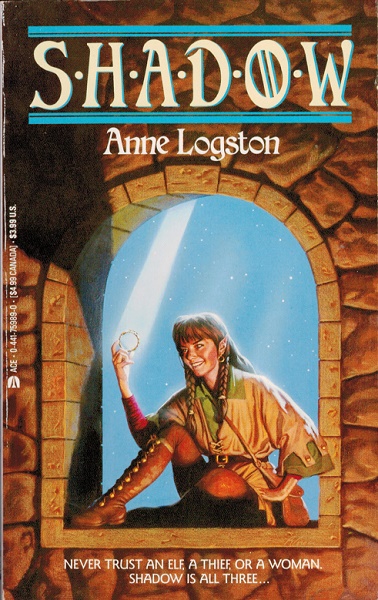

Shadow by Anne Logston. Ace Books, 1991. Shadow 1.

Anne Logston’s Shadow was a coincidental and serendipitous discovery in one of my many—perhaps too many—delvings into the deep, paper-musted mines of used bookstores. In this case, the Book Nook in Hobart, NY, a village that has branded itself as upstate New York’s “book village” for the past two decades, resulting in a charming if somewhat run-down street of five or six bookstores nestled in the eastern foothills of the Catskills. Logston was unfamiliar to me but the cover painting by Robert Grace was simple, almost mundane, in a way that stands out for fantasy mass market paperbacks of the era, and ridiculously charming, featuring the eponymous Shadow resting on a castle windowsill, a beam of preternatural moonlight illuminating the glitzy bracelet that is ostensibly the elvan thief’s most recent roguish acquisition. But best of all is the tagline at the bottom: “Never trust an elf, a thief, or a woman. Shadow is all three…”

The first warning is perplexing and slyly questions fantasy readers’ expectations about elves (but does suggest an older interpretation of elves as mischievous denizens of faerie), the second is obvious and cheeky, and the third could either have been sexist or meta. The combination of all three, though, was perplexingly delightful and I checked the first page. The opening paragraph sold me on Logston’s short little novel:

It was midmorning when Shadow rode into Allanmere in grand style in a haycart, ragged, whistling[,] and cheerfully broke. She jumped off at the Sun Gate and stood breathing the aroma of the city, a heady melange of baking bread, of tanning leather, of sweat and incense and dung. (1)

It’s pleasing, sparing prose that knows the power of a few well-chosen cues to conjure a lived reality through the senses and so create a world in just a few lines. At the same time, Logston gives us a rich sense of Shadow with just a sketch, an elf-woman who finds joy despite her hardship, who knows that whatever her circumstances, she’ll end the night with pockets full of coin, her belly sated, and a bedmate to boot. Shadow is just as the back-cover copy suggest:

She’s a master thief as elusive as her name. Only her dagger is as sharp as her eyes and wits. Where there’s a rich merchant to rob, good food and wine to be had, or a lusty fellow to kiss…there’s Shadow.

You can probably tell from these descriptions that Shadow is the quintessence of a text that is fun and very good at being fun—in quite specific ways that appeal to folks with a deep familiarity with fantasy, while also, paradoxically, being an ideal starter text for a reader not at all versed in fantasy—and needs no further justification. But it also does some things that are critically interesting and highlights a certain strategy for writing genre fantasy that is both common but usually very poorly done. And at fewer than 200 pages, it was an ideal palate cleanser after I feasted on Mervyn Peake’s Titus Groan and Robert Jordan’s The Eye of the World—two fantasy novels that could not be further from the other, except in length—back to back.

Shadow, published by Ace Books in 1991, was Anne Logston’s first novel. It was also the first in a trilogy featuring elvan thief Shadow, followed by Shadow Hunt and Shadow Dance, both in 1992. Logston was a busy author in the 1990s and, I think, one of that decade’s forgotten fantasy gems. She published 11 fantasy novels, all with Ace, between 1991 and 1999. Per a now defunct author website, Logston worked as a legal secretary throughout the 1980s, writing novels at night, before selling her first novel and quitting the legal work to focus on writing full time. It’s unclear why she stopped writing, since she was clearly successful as a midlist writer; Ace touted her growing fandom on later covers—marketing copy, sure, but with a grain of truth, since she regularly received positive reviews in sff publications. After 1999, she published nothing new and eventually got back her books’ rights in the mid-aughts, reprinting her books through Mundania Press, an Ohio-based indie publisher that mostly sold early ebooks and print-on-demand copies of books—with truly atrocious 3D digital art covers!—by established midlist authors who got their rights back and/or whose past success was not translating into new contracts, e.g. Louise Cooper, Don Callender, and Logston herself, but they also republished a great many Piers Anthony novels.

As a first book, Shadow is incredibly promising; it’s a tight package that expertly balances worldbuilding, narrative, character development, and emotional heart. It never leans on cliches (except, perhaps, to highlight their clicheness), the prose is neatly restrained and specific without succumbing to detail, and Logston is incredibly funny, having mastered good banter and clever dialogue and paired it with an impressive ability to invent scenarios to get Shadow laid. Shadow doesn’t read like a first novel, by any means, and it bespeaks a writer who truly knows and loves the genre, who feels confident in her novel’s pure simplicity, excellent humor, and endearing characters. It’s a book many established writers would be glad to have written.

The story follows, well, Shadow, who turns up in the town of Allanmere, no money or possessions to her name, having just been screwed out of her winnings from a recent heist by two dudes sketchily and appropriately named Ragman and Filch. Allanmere is a classic Fantasyland™ town. It’s large enough to have a castle and a wall, an armed guard force, an elite class of nobles, and hereditary rulers. It has a local economy that ensures there are plentiful, well-stocked markets for adventurers to purchase all manner of goods. There are wizards and thieves guilds; there are magic and potions shops and blacksmiths and drug dealers; there are unique districts where each profession plies their trade; there are restaurants and inns and dragon BBQ pop-ups aplenty; there’s a priestly class that serves a dozen different gods; there’s a town council where priests and merchants and guild masters go head to head in petty political squabbles over things like zoning rights for new buildings. There are humans and there are, much rarer, elves—but little mention of other humanoid species. There is nothing about Allanmere that isn’t described in a D&D manual—except the elves, which I’ll get to later—and that’s partly the beauty of Shadow: it’s essentially a D&D novel, but better written, better plotted, and with so much more heart and verve and fun than any D&D novel I’ve read (and the number I’ve read is embarrassing).

Shadow is a political thriller, though the stakes always feel a bit lowkey, since it seems unlikely that Shadow herself will die. How she gets out of danger (repeatedly) and how she solves the mystery structuring the novel, navigating Allanmere’s factions, and how she does so by building intimate friendships and learning to overcome her natural tendency toward lonerdom, are the heart of the narrative. It all starts when Shadow nicks a fancy bracelet from a belligerent young man, a much-disliked noble douchebag named Derek. When Shadow dons the bracelet, it won’t come off. With the help of her former adventuring pal, the Xena-like Donya (who happens to be the daughter of Allanmere’s High Lord and Lady), she discovers that the bracelet is a simple but powerful magical charm for unlocking any lock—it just needs the magic word to come off: aufrhyr. Good news follows bad news, though, as the bracelet belonged to the former master of the thieves guild, Evanor, an elf who is thought to have been murdered by the guild’s current, highly incompetent master. And the bad news keeps coming: there’s an assassin contract out on Shadow now that she has the bracelet, low-rent thieves are turning up dead, and temples keep getting robbed. The city is on edge, the thieves guild and priests are ready to go to war, and none of it seems to make sense to Allanmere’s leaders, Donya, or Shadow herself, who keeps getting implicated in various crimes she hasn’t committed. And amidst it all Shadow reconnects with her roots—a 500-year-old elf-matriarch, she grew up in the Heartwood outside Allanmere before it had transformed from the few human farms of her youth into the bustling city of today—and finds a few lovers (almost every chapter ends with her getting laid).

But Shadow unravels the mysteries that have daggers and fingers alike pointed her way, first by commissioning the Heartwood elves to make a powerless replica of the bracelet to trick the thieves guild with. Then by buying out the hit contract on her, leading to a tense confrontation with the elite assassin Blade, a mysterious woman who threatens that, by relieving Blade of her contract, Shadow owes her “three decades of [her] life” (168) (a rather confusing bargain that I don’t understand but which will likely come into play in future Shadow novels). Finally, Shadow unmasks the villain: a priest of Urex who wanted to expand the size of the temple district, which would require permission from the elves to change the borders of the city, and so went about weakening the thieves guild (a traditional locus of power for the elves who left the forest for the city) and trying to pass anti-elvan laws in the city to restrict their freedoms. The novel wraps up neatly with the priest’s comeuppance and Shadow as the new guildmistress of Allanmere’s thieves. In a nice nod to detective fiction, the novel ends as Shadow explicates the emplotment strategies of the novel—and her own genius for having unraveled everything—to her found family of friends and lovers she has come to trust, rely upon, and get high with.

Shadow is tightly plotted and quickly paced, perhaps suggesting that it is pulpily driven by narrative alone, and an admittedly simple one at that (though “simple” is not a bad thing, as the novel attests). But Logston weaves in a great deal of character development for Shadow (less so others), gestures at a wider, more complex storyworld, especially with regard to the elves, and drops subtle hints at historical and personal events that could inform later novels. Shadow begins the novel as an elf with no attachments, looking for fun and adventure, an attitude of joviality underwritten by a loneliness whose origins are twofold: first, a disconnect from the human world owing to her fear of growing close to humans she’ll live beyond, and, second, a quiet melancholy at having seen so much change in her half-a-millennium of life, during which time the experiences, people, and traditions of her youth have faded into historical obscurity, her home ravaged and forever changed by a war now centuries past, and the elves she knew now long dead. This ontological reflection on what it means to be elvan (Logston uses this spelling throughout, a subtle shift away from Tolkien’s “elven” that suggests her somewhat different vision of elves) and the affects of elvan experience of different temporalities are handled sensitively, matter-of-factly, and without turning to melodrama. Shadow considers leaving Allanmere once things are figured out—not wanting to one day sing Donya’s “mourn song” (148)—but decides, in the end, that a life of isolation is no match for the joy, camaraderie, drugs, and sexy times to be found in the company of friends like Donya, Argent, Elaria, Cris, and Tigan. And, after all, the thieves guild is a shambles and needs real leadership, lest the merchants get too comfortable with their profits.

Shadow is sappy and sincere and bawdy—and, both technically and emotionally, it’s really damn good stuff. Logston’s characters are perfectly drawn, with voices and sayings and inventive expletives (“turtle turds” and “six-fathered pisspot scraping,” both 72) that bring them and their world to lush life, ribaldly juxtaposing the modern familiarity of their speech and tone with the fantasy realm they inhabit. And Logston does it with such ease that it’s hard to forget these characters when the book closes.

In many ways, it’s surprising that I would like this book—and, to be clear, I unabashedly adore Shadow. As a general rule, I tend not to like humor in my genre fiction; hell, I rarely seek out comedy as a film or television genre. But what I’ve come to learn about myself over the past few years is that it’s not that I don’t enjoy humor but that I don’t enjoy a particular kind of humor, namely the humor in genre fiction that is often understood (especially by Americans) to be “smart,” i.e. “British humor.” Monty Python and the Holy Grail? Hate it. The Mighty Boosh? Really, no thank you. Douglas Adams? Annoying. Terry Pratchett? I haven’t read him because I dread the humor. On the American side, there’s a related but much more pun-y kind of humor in genre fiction that I also find off-putting, namely Robert Asprin’s MythAdventures series and Piers Anthony’s Xanth series, both of which I will someday force myself to read (and, yes, Pratchett, too *grumbles*).

But I’m not totally humorless and where I enjoy humor in genre is most often in TV shows and films—like Buffy the Vampire Slayer or Angel or Xena: Warrior Princess or, more recently, Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves or Baldur’s Gate 3—where the humor might occasionally comment on the genre or the storyworld but exists largely as a texture within that world, not an affective (and perhaps aesthetic) strategy for disrupting the storyworld or its genre processes (which is how I read my broad brush painting of the “British” humor above). At least, that’s my best guess at analyzing what I like about humor in these texts versus what I dislike about the others. Someone much smarter than me and much more attuned to the histories and affect of humor could say what the difference between these approaches is—and would probably lampoon me for glossing over complexities in styles/forms of humor that I’ve lumped into two amorphous categories and that I am hardly able to parse.

Logston’s Shadow is, definitively, the kind of humor I like. In fact, it put me in mind at various times of each of those texts above that I admire. Its story and situations and characters read like a masterful anticipation of Honor Among Thieves some 30 years early and it has the flair, irreverence, friendships, and sincerity of later nineties texts like Xena and Buffy. Indeed, it’s sort of a reversal of Xena, with Shadow in the Gabrielle role as the hero and Donya in Xena’s boots as the sidekick. At the same time, the novel’s focus on the politics of a town’s thieves guild and its hints at an assassins guild had me in mind of Thieves Guild and Dark Brotherhood storylines in the Elder Scrolls games Oblivion and Skyrim.

What Shadow is most reminiscent of, though, is a damn good D&D module narrated by a caring, funny, and whip-smart DM who knows how to rally the symbolic language of generic fantasy to quickly sketch the shape of a familiar storyworld but puts her own spin on key elements, and in doing so demonstrates a deep knowledge of and passion for other beloved intertexts—in this case, I think, Wendy and Richard Pini’s ElfQuest comics. This DM’s main focus is telling a damn good story, even if it’s ultimately a rather simple one, and sweeping you along with her in a mashup of swashbuckling adventure, local politics, touching reflections on identity and friendship and loneliness, and classic gumshoe detective work. And this DM is cool as fuck, too. She plays classic rock by women-led bands in the background during your gaming sessions, she probably wears a leather jacket, and she doesn’t tolerate any bullshit, especially sexism. Because there’s essentially no misogyny in this book (the three who try it get their balls kicked in and their faces trampled) and Shadow is the funnest, horniest 500-year-old elf you’re likely to meet.

My emphasis here on D&D is purposeful, since, as noted above, the premise of Shadow is basically what if D&D novel, but very good? Scholars like to quip about a text using a generic Fantasyland™ and how it represents a dreadful form of commercialism or commodification that debases what is unique and powerful about good, inventive, literary—and, therefore, original—fantasy (see, for example, Le Guin’s thoughts on commercial fantasy in “From Elfland to Poughkeepsie,” discussed at length in my essay on Eddison’s The Worm Ouroboros). But the whole ethos of D&D is that that mixing of elements in gleeful play but with reverence and love for their sources is not necessarily a bad thing. Logston shows how a generic medievalist fantasy world that assumes a whole lot about its storyworld from D&D can in fact be amazing. For a fuller discussion on iteration and its importance to fantasy, and how we can and should problematize critiques of iteration that see only “mere” imitation, see this section of my recent essay on Jordan’s The Eye of the World, where I discuss Matthew Sangster’s An Introduction to Fantasy.

Shadow’s approach to worldbuilding reminded me very much of Elizabeth Moon’s compelling, highly accomplished Deed of Pakesnarrion trilogy (1988–1989), which is set in a fantasy world that could easily be built from basic D&D rulebooks and which showcases very little invention with regard to the worldbuilding. It takes its assumptions about fantasy worldbuilding from D&D and tells a unique, powerful, and nonetheless inventive story that boils down to what happens when a fighter multiclasses as a paladin, why that change might happen, and what the implications for the character and her narrative would be. And that’s setting aside that the first novel in the series is very much a low fantasy exploration of life in a medievalized fantasy-world army, with almost no magic to speak of (when it does appear it poses a sufficient and terrifying danger); and setting aside that the series’s eponymous hero, Paks, is asexual—a rarity in any medium or genre. Notably, both Moon and Logston are writing about women characters in their fantasy worlds and deal head on with questions of genre, romance, and misogyny. The latter, in particular, is a clear theme in Moon’s series, whereas misogyny is only played for laughs in Logston’s Shadow and the joke is on the misogynists who get their comeuppance posthaste.

Logston seems to have enjoyed working in the world of Shadow and with these characters, since she not only wrote a trilogy about the elf-matriarch, but also a duology about her niece, Jael, another novel about the mysterious ancient elvan figure Greendaughter and yet another about a half-elvan woman coming to terms with her identity. (Some of her other novels might also be in this world, but it’s hard to tell without reading them, which I intend to do!) Logston’s elves are a particular draw, since they differ from the Tolkienian and subsequent D&D vision of elves, and instead have more in common with the Pinis’ ElfQuest comics, an indie fantasy series begun in 1978 that achieved such renown by the early 1980s that it was reprinted by Marvel Comics and turned into a series of novels and story anthologies (several of which were republished by Ace in the 1990s). Importantly, the Pinis’ elves are not elevated beings who stand above humans (though humans are largely depicted as savage and uncivilized), but instead who stand apart, not as paragons of nature, shaping it into giant forest cities like Lothlorien, but as beings who live alongside nature, adapting to different environments and seeking to live in harmony—inspired, no doubt, by (white people’s ideas about) Indigenous cultures of North America. Indeed, There are parallels between Logston’s elves and real-world Indigenous peoples, especially in some of the language used about elves in the distinction between “citified” elves who have become “self-controlled and polite” (41, 130) and those who remain in the forest, but this is not explored and remains a potentially problematic, unreflexive element in Logston’s writing.

Logston’s elves organize their society in tribes, just as in ElfQuest, and many elves choose to stay separate from human society, which is highly prejudicial against them. While elves can be long-lived, few have lived more than a century or two; Shadow is a rarity at her age and revered as a matriarch by the younger elves she encounters, though she is by no means thought of as “old.” War and conflict with humans over land have driven the elves deeper and deeper into the woods, where they live in relative isolation. Allanmere might be a rarity among human polities, since its founding charter—brokered between the humans of the city and the elves of the Heartwood several centuries ago—requires that one ruler be human and the other elvan, virtually necessitating intermarriage. Still, for all that it represents an ideal of racial coexistence, the charter is not respected by most of Allanmere’s elites, hence the plot central plot by the priest to drive elves out of political life, strip them of political power and representation on the City Council, put legal limits on their freedom, and push them back into the forest. The elves that do live in the forest are largely unfamiliar with the rites and customs Shadow grew up with and she is seen as a keeper of knowledge by the younger elves. Moreover, Longston’s elves are incredibly sexual and their mating practices are largely for pleasure, since elvan women rarely “ripen” in Logston’s wording (29). They are also musical people, but much more so they are a culture of dance, one wherein dances have ritual value, are passed down the generations, differ across communities, and can be used to perform magic. Logston draws on Tolkienian and Pinian elves, Victorian faerie stories, and even Icelandic tales of the huldufólk—or hidden people, a term Logston occasionally uses for the elves—to create something at once familiar and her own.

The story of Greendaughter illustrates this rather clearly. Shadow is the only elf in the Heartwood to have encountered Greendaughter, a mysterious figure belonging to the earliest lineage of elves in the region, so ancient that she seems more forest deity than mortal being. The younger elves call her “wood sprite” and revere her as the avatar of Mother Forest but Shadow is old enough to know she is an elf and her name was once Chyrie, “born in the time when your Eldest’s grandfather would have first drawn breath,” she says to Otter and Hawk (77). Shadow recounts to those young elves a lengthy experience with Greendaughter from her youth (77–82) and she meets her again in a moment that feels pulled right out of ElfQuest but marries Shadow’s nonchalant approach to the grand with a sort of Victorian faerie-esque presentation of Greendaughter as an unknowable, powerful, childlike being. Greendaughter, to Shadow, is the vision of what has been lost to elf-kind by the progress of humanity, but she also represents an unrecoverable past—not necessarily something to return to, simply something to mourn as one might mourn the inevitable passage of time—and perhaps a warning of what isolation (for Shadow herself, for the elves generally) can do to a person who can live as long as an elf. The last thing Shadow wants is to drift into future millennia as a childlike spirit of the forest. Her decision to commit to staying in Allanmere, to face the consequences of being elvan in a world of human temporality, is telling. It’s not a rejection of elvanness but a reframing of the elvan relation to time and being in the world, and one she can live with, given enough laughs with friends, purses to pinch, and lusty fellows to bed.

Anne Logston’s Shadow is an inventive, charming, heartfelt treasure of a fantasy novel and a poignant counter to the narrative that fantasy in the 1990s was all medievalist epic fantasy doorstops about chosen boys doing special things. A chance encounter and a whim taken on a cover brought me one of my most enjoyable reads this year. Logston was a surprising and exciting discovery—a writer who spent the 1990s writing incredibly good fantasy novels that brilliantly iterated on D&D-style generic fantasy, gave it heart, brought the humor, focused on the experiences of women, and did it with style and verve, easily punching above her weight with a first novel that really impressed me.

Will I read more of Logston? As Shadow would say: Bet on it.

To get notifications about new essays like this one sent directly to your inbox, consider subscribing to Genre Fantasies for free:

One thought on “Reading “Shadow” by Anne Logston (Shadow 1)”