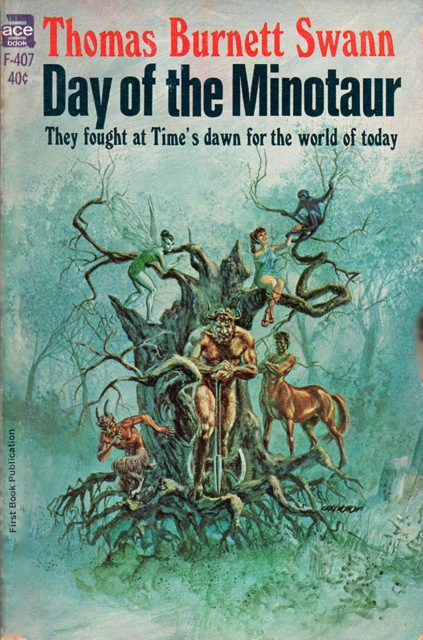

Day of the Minotaur by Thomas Burnett Swann. Ace Books, 1966. Minotaur 3.

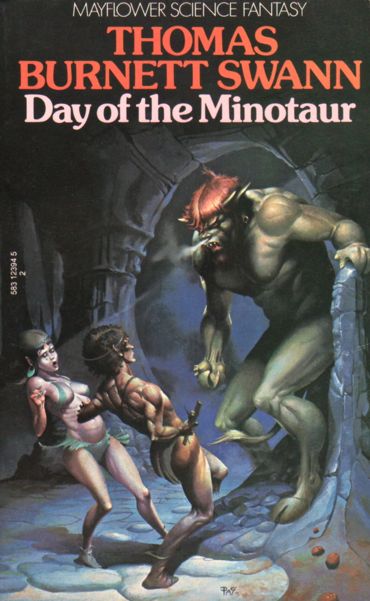

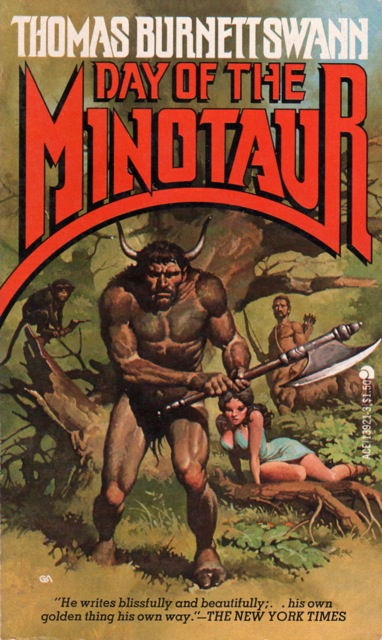

From left to right: Ace cover by Gray Morrow (1966), Mayflower cover by Brian Froud (1975), Mayflower cover by Peter Jones (1977), Ace cover by Gino D’Achille (1978). All courtesy of ISFDB.

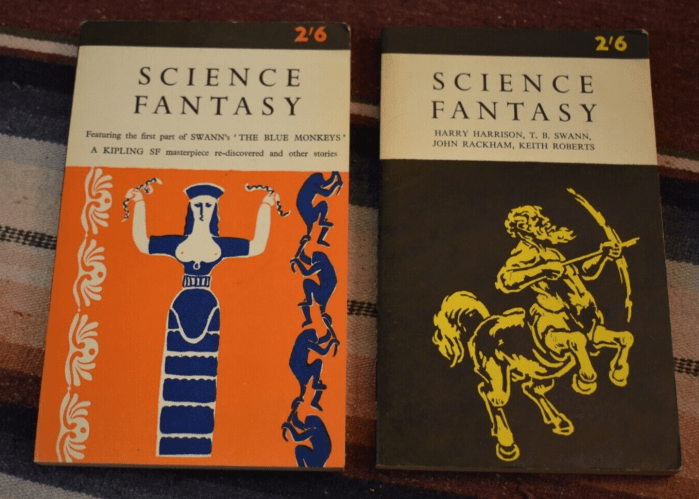

Prior to 1966, Thomas Burnett Swann was a relative unknown in the American sff scene. His stories had mostly been published in the UK, in Science Fantasy magazine, a sister publication to the magazine that would become the early locus of the New Wave: New World. In the early 1960s, Science Fantasy was shifting more clearly to fantasy stories under the editorship of John Carnell, and Swann’s provocative, inventive fantasies of the ancient and medieval world, tweaked to his own unique vision of the mythic past, were a staple of the magazine in the 1960s under the editorship of Kyril Bonfiglioli. The stories that would become Day of the Minotaur were initially serialized in 1964–1965 under the title “The Blue Monkeys” and reprinted in full in the British anthology SF Reprise 3 in 1966, before eventually finding their way to the US in the form of an Ace Books paperback, under the title that we now know it, and with a cover by Gray Morrow that captures both the narrative’s ancientness and anachronism in one breath (though I much prefer the first two Science Fantasy covers featuring the story).

Donald Wollheim was the editor at Ace at the time and Day of the Minotaur was published hot on the heels of the Tolkien pirating incident of 1965, during which Wollheim—seeing (or pretending to see) a loophole in US copyright law—published unauthorized mass market paperback editions of The Lord of the Rings. Those paperbacks sold like gangbusters, 100,000 copies in a few months, before Ace was promptly sued and rival publisher Ballantine worked out a deal with Tolkien to publish the “authorized” editions (we know where that led). But the Tolkien incident showed a taste in the reading public for the fantasies of Tolkien and Ace responded with, among other things, Thomas Burnett Swann. Whether Wollheim liked Swann’s writing or the sales revenue his books brought is unclear, but Swann’s career and his familiarity to readers today owes much to Wollheim. Ace published Day of the Minotaur and three other Swann novels (The Weirdwoods, Moondust, and The Forest of Forever) and two story collections (The Dolphin and the Deep and Where Is the Bird of Fire?) between 1966 and 1971. And when Wollheim left Ace and founded DAW Books, he published six more of Swann’s novels between 1972 and 1977.

Given this context, it’s unsurprising that when Day of the Minotaur debuted in paperback, it was likened in its marketing copy to “the marvel-packed sagas of J.R.R. Tolkien,” as well as to “the sweeping adventure-tales of Mary Renault, and the sheer story-telling magic of Jack Vance and Edgar Rice Burroughs.” None are great comparisons, but what they get at is an epic story, told in the increasingly market-visible genre of fantasy, and recasting the ancient history of our world. Swann’s first novel, like all of his novels, was remarkably short at 159 pages (in the smaller Ace paperback size, that of the Ace Doubles in dos-à-dos binding, a good half-inch shorter than the industry standard size), practically a novella, and so defies the Tolkienian comparison for sheer lack of length. What it offers in brevity, Swann’s novel doubles in vision, for here begins the story of the prehumans—the mythic peoples of the ancient world driven to extinction by the coming of human civilization—that will preoccupy most of Swann’s career for the next decade, until his untimely death from cancer in 1976.

Of all Swann’s sixteen novels, it’s Day of the Minotaur that David Pringle includes in Modern Fantasy: The 100 Best Novels, 1946–1987 (1988). Pringle doesn’t appear to have read Swann widely, however, as his final comments in the entry on Day of the Minotaur reference only Swann’s work prior to 1972 (more than half of his novels were published in 1975–1977), he refers to a short story collection as a novel, and he ignores that Swann wrote two further novels—not one—about the eponymous Minotaur Eunostos. Moreover, Pringle’s selection doesn’t seem to explain why this novel is important, let alone why Swann is; more than anything he critiques Day of the Minotaur as having a “cosy, Walt Disney Touch,” and offers in evidence a paragraph describing Eunostos’s home. Pringle balances this critique of the “over-sweet, children’s-story qualities” by pointing to the novel’s “playful sexiness” and “an underlying theme of somberness.”

It’s probably a bit irrelevant to complain about Pringle’s choice nearly four decades later, but it is a strange one. Everything that is good and singular about Swann’s writing—and which I have heavily (and rightly) praised in my essay on what he considered his “best” novel, Lady of the Bees (1976)—is here in Day of the Minotaur in nascent form, partly developed, not yet fully birthed like Aprhodite from the head of Zeus, and so a little clumsy for its infancy but shining with potential. To that end, Pringle’s critiques are spot on, and it is also these three elements—what Pringle calls coziness, sexiness, and somberness—which grow and transform across Swann’s oeuvre and mature in surprising ways.

Day of the Minotaur is the story of Eunostos the Minotaur, last of his people, and of Thea and Icarus—niece and nephew of King Minos, daughter and son of Aeacus; Icarus is not that Icarus, son of Daedalus—in the waning days of the Bronze Age (c. 1500 B.C.) on the island of Crete, the heart of Mycenaean Greek culture. The novel is about the fate of the six “races” of the Beasts (the novel’s term for what Swann will later come to call prehumans) as their time is waning due to the onslaught of human civilization. In the fall of the Beasts, Swann mirrors the fate of the “civilized” Cretans (Mycenaean Greeks) at the hands of the barbaric Achaeans (the Homeric term for Greeks generally, which in that usage covered the entire Greek cohort attacking Troy, including Cretans led by Idomeneus, grandson of Minos; “Homer” was singing his epics some 600-800 years after the events mythologized in the oral epic tradition, so his own terms are likely anachronistic, especially given that the Hittite term for the Mycenaeans (Ahhiyawa) is cognate with the Greek word for the Achaeans (Akhaioí)—isn’t etymology frustratingly great?).

Swann’s Beasts include the Minotaurs (represented now only by Eunostos), Centaurs, Dryads (pointy-eared, elf-like women), Panisci (fauns, satyrs, “little Pans”), Thriae (bee-people whose bee-ness is more in their social organization than their looks, for they are slight, winged people, like fairies, and all extremely attractive—and collectively devious and treacherous), and the Bears of Artemis. The last are the strangest of Swann’s creations in Day of the Minotaur. They are briefly referred to as “minkin,” a mythic race that appears in later Swann novels but with seemingly no relation to the Bears here. The Bears are furry all over, exceedingly cute, and always hungry. In a 1974 interview, Swann claimed A.A. Milne, about whom he later wrote a monograph, as his “first and greatest” influence, and specifically that the bears in his own novels “are my personal signature.” Also in this novel are the Telchines, ant people who act as Eunostos’s servants and are expert craftspeople, and the Striges, small vampire-owls. Neither are regarded as “races” alongside the other six races of Beasts, but they seem to be a second order of being, more animal than people. There are also the blue monkeys, which in this novel are simply blue monkeys who have a caring fondness for Thea; they are not the mysterious Telesphori, also referred to as blue monkeys, of later Swann’s work (see, e.g., Lady of the Bees).

Notably, while mythological beings are real in Day of the Minotaur, the gods and the supernatural are largely distant from the narrative, and figures who were mythological (or who were perhaps historical figures mythologized by tradition and epic), such as Minos or Aeacus or Ajax, are here specifically historical. There are no references to gods, except as religion, and there are no mentions of anyone being the descendant of a god (though this is true in later novels); moreover, the Daedalus/Icarus incident is written off as a failure of engineering and the advanced engineering capacities that such a myth might be historically reimagined to gesture to are present throughout Swann’s late Bronze Age Crete, from personal glider vehicles launched by ballista to a giant robot (Talos) to indoor plumbing (the latter of which was a reality in Knossos). Unlike in the work of Mary Renault (which Swann admired but decried for its lack of fantasy), the non-humans of myth were in fact non-human. In other words, Swann naturalizes the storyworld, he makes the unreal into real, historical fact. That which, in our world, became legend and mutated into myth—such as Minotaurs and Centaurs—is understood as part of a social and historical process, a narrative transformation among humans caused by bad historical memory and, more importantly, their fear of the non-human. For this reason, Swann calls his mythological beings Beasts, signalling that the term has been stripped of its original meaning in order to denigrate the memory and truth of the prehumans.

Swann both naturalizes myth and historicizes it in Day of the Minotaur, beginning the novel with a frame narrative that gestures to its historicity. This is not a novel, we learn, but “one of the first histories, an authentic record of several months in the Late Minoan Period,” it is a manuscript discovered by an archaeological team at Knossos, the translation of which was made possible by Michael Ventris’s deciphering of Linear B, the writing system for Mycenaean Greek, in 1952 (6). The translation is courtesy T.I. Motasque, Ph.D, Sc.D., L.L.D at the fictional Florida Midland University (Swann was himself, for a time, professor at Florida Atlantic University), who suggests that the “breathtaking” revelations in this manuscript will “necessitate a complete reexamination of classic mythology, since many of our so-called ‘myths’ may in fact be sober history” (7). This, in a nutshell, is Swann’s entire project as a fantasist, as the author of more than a dozen novels about the history of fall of the prehuman world, and it begins with a clear statement of artistic purpose here in Day of the Minotaur.

The first Ace edition’s cover copy describes the novel ostentatiously: “They fought at Time’s dawn for the world of today.” But this is not actually what the novel is about and is in fact a misreading of the novel, for the Beasts do not fight for our world—which is in fact the fallen world, the world of human civilization and its violences—but for their own world and against their extinction. When the novel opens, Mycenaean Crete is on the wane as a major power in the Mediterranean and is threatened by invasion from the Achaeans. Crete is positioned here as the height of a complex ancient civilization, the equivalent of Egypt and Babylon, while the Achaeans are lusty, violent, unwashed barbarians. It’s a replay of so many fall of civilization narratives—only, because this is Swann, it has a subversive purpose. For the Achaeans (a term deliberately chosen by Swann to invoke Homer) are the ancient heroes of the Western Classical canon, the source of Western civilization, its object lessons, its paragons of power and masculinity and what it means to be Western. They are here cast as the barbarians, not only ravaging the older, nobler civilization of Mycenaean Crete, but also an ancient, more natural one: the Beasts. We learn, too, that although the Cretans are an older people, much of their advances (and even their language) were learned from the Beasts. But though the Cretans are the waning civilization set against the barbarism of the Achaeans, Eunostos tells us how the Beasts once lived freely across all of Crete, how they welcomed and mentored the Mycenaeans, but were ultimately driven to a small enclave in a secret, cliff-protected forest by the Mycenaeans’ fear. In classic Swann fashion, the story of the ancient world is a story of successive waves of violence played out across succeeding, increasingly barbaric human civilizations, and the tragic Fall of the world as the prehumans are slowly, cataclysmically driven into the shadows.

The narrative of Day of the Minotaur is split into four movements. In the first, Thea and Icarus fall into the hands of an invading Achaean general, Ajax of myth—the Greater or the Lesser, it’s unclear. After his attempted rape of Thea, who mars his genitals in some undescribed way, Ajax leaves Thea and Icarus at the cave of the Minotaur, a sacrifice to the monster feared by the Cretans. But Eunostos is far from a monster, he is not even bull-headed, but in Swann fashion is only partly recognizable from the myths: he is as depicted in Morrow’s 1966 cover, a very hairy man with horns, a tail, and hooves, more human than most depictions of minotaurs we’re familiar with. Eunostos is kind and gentle, and recognizes immediately that Thea and Icarus are the half-children of a Dryad, that he knew them as babies before their father Aeacus took them from the Forest of the Beasts to live in the human world.

In the second, Thea and Icarus go to live with Eunostos in his giant tree fortress in the Forest. This is the segment Pringle decries as Disneyesque. But this is something we see throughout Swann, that the “monsters” live domestic lives of comfort and joy when they are safe from human interference. What’s particularly clear in this section is that Swann appears to be trying to write an Austenian pastiche focused on manners and the slow dawning of love between two unlikely romantic subjects—Eunostos and Thea—as each has to grow in relation to what the other teaches (Swann nods to this rather clearly with the title of chapter four, “Domestications and Domesticity”). Here, Thea and Icarus are exposed to the world of the Beasts, their different social mores (especially with regard to sex and sexuality, which are freely practiced and discussed among the Beasts), and the tragedy of human violence against them. Icarus comes to embrace being a Beast—a half-Dryad—while Thea rejects her heritage and tries to make Eunostos more human. This section is the cutesiest portion of the book and is probably where Swann’s weakness at this early stage in his career shows through. But even here, what should seem silly, like the Bears of Artemis, often turns to the serious and the sympathetic.

In the third, war comes to the Forest of the Beasts when Ajax discovers that Thea is not dead but living happily among monsters. So Ajax bribes the duplicitous Thriae to capture the siblings and deliver them to the Achaeans. When this plot is thwarted by the observant Pandora, an adorable Bear of Artemis, the races of the Beasts hold a conference and banish the Thriae from the Forest while asserting their kinship with and acceptance of the half-Dryad siblings. But the decision to banish the Thriae and protect the siblings leads to the Beasts’ doom, for the Achaeans are both greater in number than these last of Beasts and are trained killers who have honed their blades and skills conquering across the Aegean. The war goes disastrously for the Beasts; all of the male Centaurs are killed, only a handful of their children and women survive and many of the Panisci and Dryads die, too, while the Thriae join the Achaeans. Through a devious plan that involves feeding the victorious Achaeans poisoned blue monkeys (hence the original title), Euonostos and Icarus overthrow the Achaeans, saving both the Beasts and Crete—for a time.

In the fourth and final section, the siblings return to Knossos and their father, Aeacus, while the Beasts attempt to rebuild. But in recognition that the Achaeans will only return and that the downfall of Mycaenean civilization is inevitable given the rising power of the mainland Greeks, Aeacus offers the Beasts three ships to take them back to the Isles of the Blest from which they emigrated centuries before. Eunostos is appointed leader of the Beasts and agrees to take them on this journey, to abandon the human world once and for all. Here the historical document of the frame narrative ends, but Swann gives us a few more pages after the scroll is finished and sealed away in Knossos. In these last pages, Thea and Icarus come to join Eunostos on the Beasts’ journey, the former having accepted her Beast identity. In this final meeting, Thea declares that she will go but only as Eunostos’s wife:

“How shall we meet except through the flesh? The soul must see through the body’s eyes and feel through the body’s fingers, or else it is blind and unfeeling.”

“You say that our bodies should meet[,” Euonostos said. “]But you are beautiful—and I am a Beast.”

“Yes, a Beast like my own mother, and lordlier than any Man I have ever known! Do you know why I tried to eclipse you with clothes? Because you stirred me with feelings which had no place in my tidy garden of crocuses.” (158–159)

Though Eunostos is lord of the Beasts, he has come to see himself in and through Thea’s eyes as something if not monstrous, then at least as a kind of being marred by his own nonhuman body. He hovers, in her eyes, between the human appellation of beast and his own people’s noble use of the term. But Thea at once rejects that. She instead embraces her Beast heritage, dissolves the opposition between beauty and Beast, between human and monster. Here there is no transformative kiss, but rather a Shrek-like acceptance of a new regime of beauty and propriety, of what it means to be noble. This theme recurs throughout Swann’s fiction, which regularly troubles the monstrous by destabilizing the human.

The destabilizing of ontological and epistemological regimes is at work throughout Day of the Minotaur. Swann regularly challenges notions of normality, of what it means to be civilized, and sexual mores—especially women’s sexuality, which here embraces polyamory and free love; and also the fluid boundaries of male sexuality, which here is merely hinted at, though queerness is much more explicit in later novels. Swann is, yes, cutesy, sometimes overly so in Day of the Minotaur, but his vision of the prehumans is nonetheless a rather novel one, and the occasional cutesiness of figures like the Bears of Artemis is tempered by the Thriae, the Dryads, or the Centaurs, not to mention the formic Telchines, who sacrifice themselves to save the half-Dryad siblings from the Achaeans in a surprisingly touching scene. Swann is, more than anything, a writer of emotions—of sensitive, gentle characters surviving in a brutal world. This is at times awkwardly done but a hallmark of his fiction.

Day of the Minotaur is a glimpse at Swann as he was just starting to realize his unique, powerful approach to fantasy, experimenting with emotion and melancholy and beauty, and turning narratives of Western civilization and its triumphs on their heads. Perhaps the novel’s most powerful theme, which Swann will address in one form or another over the next decade, is that of our relationship with nature, put so elegantly and self-questioningly by Eunostos, speaking of his home:

You could almost say that I had captured a little corner of the forest. No, not captured. I have never liked that word. Rather, I had trusted myself to the forest, given my safety into the keeping of her labyrinthine roots, which held the earth above my head and below my feet, supported and sustained me. (44)

This notion of a right relationship with nature is reflected in the communalist Beast economy, in the Beast’s belief in a singular Mother Goddess of nature, and in Eunostos’s horror when he discovers Thea has cut flowers from his garden, just to capture their fleeting beauty as they die in a vase. Cutting flowers. A small thing, a cute thing, a Disneyesque thing—a Minotaur gardener?!—but a notion in Swann’s fiction that reaches to grand heights, that touches the very heart of Western civilization’s self-conception, that castigates greed and power and all that has come to define a wrong relationship with nature. In Swann’s prehuman world there is no ethical form of capture. We have only to trust ourselves to the forest.

Day of the Minotaur puts on eager display the perplexing freshness of Swann’s vision of the prehumans, his idiosyncratic approach to antiquity, his rejection of antiquity’s greatness, and his reframing of ancient civilization as a period of violence that silenced an older, nobler world. Swann would spend the next decade playing with these ideas and refining them to a crisp clearness. Despite his occasional clumsiness in this first novel, Swann’s writing abounds with beautiful passages that capture the poetic, reflective texture of his prose and he shows himself to be concerned with affect and beauty and most especially with love in its many complex manifestations. Day of the Minotaur is an auspicious beginning for Swann’s career as a fantastist, even if it is just that—the work of a beginner. But a novice with a vision? A novelty, indeed!

To get notifications about new essays like this one sent directly to your inbox, consider subscribing to Genre Fantasies for free:

Editorial note (9/16/25): After I published this piece on Day of the Minotaur, my colleague Nat Harrington was prompted to read the book and wrote a great review, which makes some connections with Samuel R. Delany’s Tales of Nevèrÿon that I did not notice for I have yet to venture into those Delany waters (others, though, especially Dhalgren, I have braved).

12 thoughts on “Reading “Day of the Minotaur” by Thomas Burnett Swann”