Titus Alone by Mervyn Peake. 1959. Ballantine Books, Oct. 1968. [My version: Fourth printing, Sep. 1973]

This essay is part of Ballantine Adult Fantasy: A Reading Series.

Note: As an associate editor for the SF section of Los Angeles Review of Books, I commissioned Aran Ward Sell’s piece on Peake’s Titus Alone. It’s an excellent essay on the “failures” of Titus Alone and a perfect companion to this entry in the BAF reading series.

Table of Contents

Some Context for Titus Alone

Reading Titus Alone

The Problem of Modernity; Or, Why Titus Alone Is Difficult

Parting Thoughts

Contrarian that I am, when I learned that Titus Alone, the third novel in Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast series, was nearly universally disliked, I challenged myself to like it. And in reading the novel, I had to once again confront the truth that I am not so different, that whatever contrarian strain might run through my psyche, it must surely be a form of self-deception, for it proved me yet again a fool. I now embrace the disappointing verdict of the collective that sits in judgment of Titus Alone. I am one of you, dear reader, and I do not like this novel. But it is fascinating, almost a trainwreck, but a literary disaster with something to say, even as it tears its way forward, toward something new for Peake’s series. Let’s listen to Peake’s figurative final words, to the book that he struggled to write to the very end. Let’s try to excavate something of value in Titus Alone. It won’t be hard; neither will it be pleasant. But what’s literary criticism without a little productive unpleasantness?

Some Context for Titus Alone

Titus Alone is a major change from the previous novels, Titus Groan and Gormenghast, in several key and consequential respects.

First, Titus Alone no longer takes place in Gormenghast but in the wider, hallucinatory, even science-fictional world beyond the eternal castle—in an “outer space” that has absolutely no knowledge of the Groans or their demesne, and whose inhabitants understand Titus by turns as a romantic, a lunatic, or a criminal. Thus, as Titus travels ever onward, hunted everywhere by two helmeted men whose purpose is never made clear, he increasingly doubts whether Gormenghast was real. He is also angry, even cruel, and emotionally volatile throughout the novel, hurting everyone who gets close to him.

Second, where the first two Gormenghast novels are textured by a claustrophobic Gothicness (indeed, the first US hardcover edition of Titus Groan subtitles it “a Gothic novel”) and by Dickensian social caricature (Michael Moorcock has also interestingly compared the novels to Zola), Titus Alone is better described as anxiously Orwellian. The tone and even the genre trappings of the novel are thus radically different, even if—as James Gifford gestures to but does not fully explore in A Modernist Fantasy—the critique of power and of modernity begun in the earlier novels is carried forward here, though arguably with greater clarity.

Third, where the previous two novels open sprawling vistas onto Peake’s vision of Gormenghast, composed of lengthy chapters and equally extensive paragraphs that overflow with description and seek ever to bring the impossible world of the castle to life, Titus Alone is not only less than half the length of both Titus Groan and Gormenghast, but its chapters are on average two to three pages, its descriptions foreshortened, and the reader’s experience of the brave new world Titus traverses is entirely discombobulating, reflecting his own increasing paranoia and self-doubt. Language, in Titus Alone, is difficult, slippery, confusing; Titus himself rejects it as an imperfect medium for interpreting the world: “I am sick of language” (120).

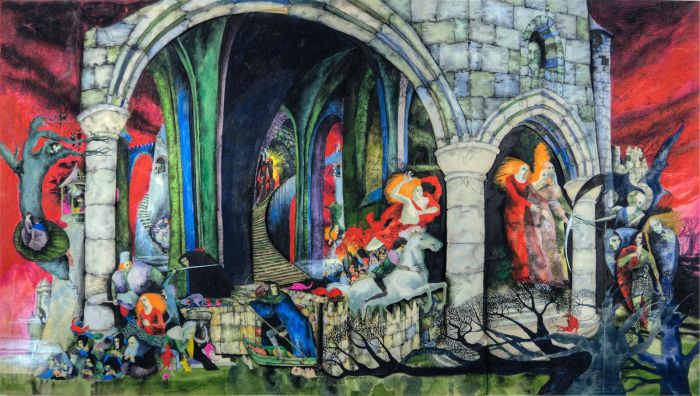

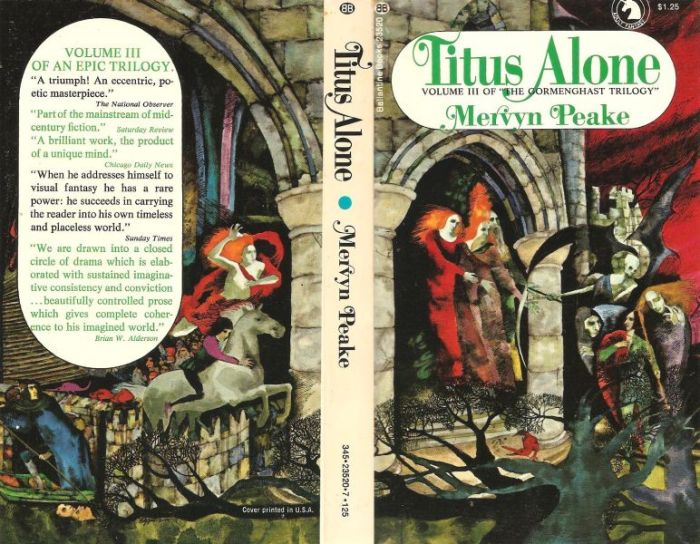

Fourth, the novel was written under extreme mental and physical duress, since Peake succumbed to a rare form of early-onset dementia that affected memory, reasoning, and motor function. Peake’s wife, Maeve Gilmore, characterized his attempts to start the fourth book, Titus Awakes, as such: “The first pages [are] those that were tortured into life by the man who struggled with his failing brain, and his failing hand to conjure up so enormous a task.” No doubt this was also the case toward the end of his writing Titus Alone, which took nearly a decade despite its paucity in comparison to the previous two novels, which were together written in half that time. Without Peake’s careful oversight, his editors at Eyre & Spottiswoode published Titus Alone in a sloppy, pseudo-unifinished state in 1959. As Peake’s health continued to worsen in the 1960s, New Worlds editor Langdon Jones and Oliver Caldecott, urged on by Michael Moorcock and Gilmore, collaborated to secure the legacy of Peake’s writing. Jones discovered that the original Titus Alone manuscript had been botched by Peake’s editors and Caldecott agreed to publish a new, “restored” version when he became an editor at Penguin. Eventually, Eyre & Spottiswoode released the restored edition in hardcover (see Moorcock’s discussion; a note on the restorations appears in the 1970–1971 editions as well as in all later reprints). But these new paperback and hardcover editions didn’t appear until 1970–1971; Peake died in 1968. Titus Alone first appeared in the US in 1967 as a hardcover by Weybright and Talley before being republished in paperback by Ballantine (I hadn’t realized until now that Bob Pepper’s Ballantine covers for the Gormenghast novels—part of a single painting, shown below—first graced the Weybright and Talley hardcover of Titus Alone; they don’t appear to have published either of the other novels). Thus, the Ballantine edition is not the restored edition.

All of this is important context for reading Titus Alone and thankfully was already known to me when I started the novel. Without it, the novel is likely a major shock. Peake’s health problems no doubt played a role, perhaps reflected in the increasingly anxious, paranoid, frantic characterization of Titus, his recognition of how he lashes out while not wanting/meaning to, and his search for identity. Or, rather, his desire to prove that his identity is real, is his; that he is someone and not a placeless, unmoored being. But leaving this aside, Titus Alone’s major differences from the first two novels of the series seem motivated and purposeful, and it would be a critical shame to write them off as simply—well, he got sicker and sicker and wrote a bad novel in a poor effort to see his vision of Titus’s story through to the end. That’s a lazy response, even if you don’t like the novel, and I would contend that even Peake in good health might have written a very similar novel. I also have an inkling that those who enjoy postmodern literature (I do not!) would find Titus Alone to be the most provocative novel of the bunch.

Reading Titus Alone

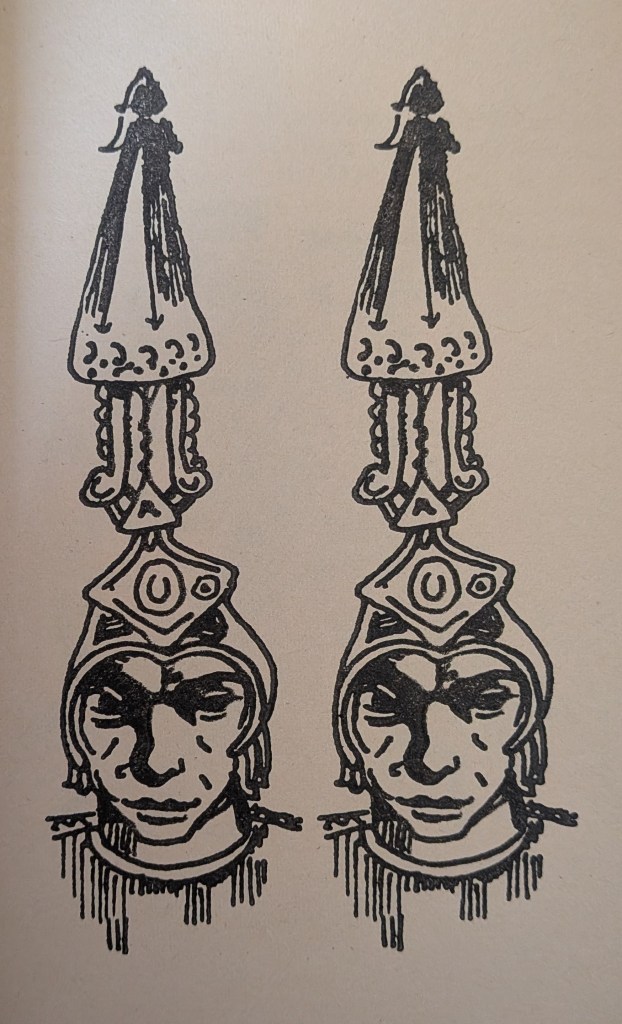

The novel begins not with words, but with images, full page illustrations from Peake’s own sketchbook. Such illustrations grace the other two novels in Ballantine’s editions as well, but after the title page Titus Alone starts first with the striking drawing of two helmeted figures (see Fig. 2 below) before proceeding through sketch-like line drawings of the Countess, Fuschia, Flay, and Barquentine that originally appeared in Titus Groan. The presentation here is precise: we are confronted immediately with the unknown, with a perplexing image of potentially Gormenghastian decorum (not that we ever saw soldiers or police in Gormenghast) followed by images of people who made a major impression on Titus during his life as earl: his distant force of a mother, his beloved and tragic sister, his greatest supporter and early exemplar of adventurous freedom, and, lastly, the man who embodied the Ritual he rebelled against—so many memories of Gormenghast, all Titus has left as he ventures from home. And the helmeted figures, not sketches but crisply drawn in bold lines, filling nearly the entire page with their pompous helmets and menacing visages. This illustration is repeated four other times at pretty regular intervals throughout the novel (7, 87, 167, 257), nearly rivalling the number of other illustrations in the text (six, three of which depict Muzzlehatch).

Following the initial cacophony of illustrations, Titus Alone starts by locating Titus—or, rather, by failing to locate him, for he is lost, adrift in the world, somewhere but nowhere he or we know—sometime after he has left the castle, maybe days, maybe weeks, maybe years:

To the north, south, east or west, turning at will, it was not long before his landmarks fled him. Gone was the outline of his mountain home. Gone that torn world of towers. Gone the gray lichen; gone the black ivy. Gone was the labyrinth that fed his dreams. Gone ritual, his marrow and his bane. Gone boyhood. Gone.

It was no more than a memory now; a slur of the tide; a reverie, or the sound of a key, turning.

From the gold shores to the cold shores: through regions thighbone-deep in sumptuous dust: through lands as harsh as metal, he made his way. Sometimes his footsteps were inaudible. Sometimes they clanged on stone. Sometimes an eagle watched him from a rock. Sometimes a lamb.

Where is he now? Titus the Abdicator? Come out of the shadows, traitor, and stand upon the wild brink of my brain! (1)

Loss, confusion, memory—distance from Gormenghast, both physical and mental—pervade the opening paragraphs and inflect Titus’s every step throughout the novel, as does his increasing fretting about having betrayed his family, weighing heavier and heavier on his heart, driving him to depths of depression and confusion, fueling his anxiety about his own being (a resonant “whom am I?!” suffuses the text), and provoking his cruelties toward the people he meets. (Also, note the curious and telling invocation of “my brain!” by the narrator, the only instance of first person in the narration.)

The plot is both simple and convoluted. In short, Titus discovers a city, something he did not know could exist, and his adventures take place in and around and beneath this city. If the flood in Gormenghast and its effects on the social world of the castle can be read as an allegory for Britain during World War II—and the fight against fascist authoritarianism in the form of Steerpike—then the city in Titus Alone would seem to be a stand-in for postwar modernity, for a society rebuilding itself, and at the same time confronting the new Cold War. A 1950s modernity pervades the city, as does Peake’s reception of the modern and its contradictions. Cars and other, often unidentifiable machines are depicted as monstrous. Society is split between an impoverished underclass living in the sewers of the Under-River; the gaudy rich in their homes of metal and plastic, protected by the police and the lively technological apparatuses of the surveillance state (e.g. robotic spy devices); and those few men who practice something like freedom, and so are branded criminals, like the enigmatic, gaunt giant Muzzlehatch with his menagerie of zoo animals.

Titus traverses the world in and around the city and enters the territories of these various classes (including, in the final third, the realm of the obscenely wealthy: the owners of the means of production). As he explores the rungs of the city’s socioeconomic ladder “in search of his home and/or himself” (187), his provenance is always doubted, he is here branded a lunatic, there labeled a criminal, he is sought by the police, goes into hiding, is captured, is released and vouchsafed by a kind stranger, and so on. Titus makes few friends, among them Muzzlehatch and Juno, but keeps them at a distance and burns bridges with regularity—though again and again he finds himself saved by Muzzlehatch, who cares for the young Titus as he would his own beloved zoo animals, slaughtered by the state when it is discovered he harbored Titus.

And throughout it all, Titus is pursued by the two helmeted men whose illustration began the novel and who reappear with clockwork regularity, marching side-by-side through this horribly modern world in constant pursuit. The figures put me in mind of the entity in It Follows and they are given no explanation in the text, not where they come from or what their purpose is. When they finally capture Titus in the climax of the novel, they do so for no explainable reason (and Titus is saved by Muzzlehatch and a few cultists from the Under-River who have come to view Titus’s story of Gormenghast with an almost religious fervor). My reading is that these figures were dispatched by the Countess to bring Titus home, but nothing in the text explicitly supports this theory.

The novel ends with a grotesque reenactment of Titus’s own memories of Gormenghast. As background: Titus gets sick and is nursed back to health by Cheeta, the daughter of a rich factory owner, one of the major powerbrokers in the city. In his febrile delirium, Titus unknowingly recounts the details of the previous novels’ plots to Cheeta. When he awakes and Cheeta greets him as “Lord Titus of Gormenghast, Seventy-Seventh Earl”—whether because she believes him and is attracted to his title, or because she wants to play games with him, is always in question—Titus proclaims:

What a face you have[. …] It’s paradise on edge. Who are you? Eh? Don’t answer. I know it all. You are a woman! That’s what you are. So let me suck your breasts, like little apples, and play upon your nipples with my tongue. (195)

Non-chalantly, Cheeta replies, “You are obviously feeling better” (195). My margin note reads, “uh, wtf?” but this moment is the culmination of Titus’s continual dehumanization of the women who show him affection and care throughout Titus Alone, from Juno—one of his rescuers and his first experience of mutual love and affection, whom he ultimately leaves for fear, essentially, that she is smothering him and distracting him from his search for “home and/or himself” (187)—to the Black Rose—a woman who survived a concentration camp and who fixates on Titus, who rescues her, but whom Titus harshly scorns the attentions of—and now to Cheeta. While Cheeta never sleeps with Titus (something that irks him greatly), she is increasingly perturbed by his manner toward her and, after one too many rude interactions with Titus, she decides to punish Titus by attempting to drive him mad.

Cheeta, with all her wealth and social connections behind her, organizes a mass cosplay of Gormenghast. The scene is the Black House, a ruin deep in the woods around her father’s massive estate. The cast are the various elites of city high society, who come for the fun and to reprimand the mysterious upstart Titus who pretends, in their eyes, to a position of nobility. The Black House has been fixed up to resemble a Gothic castle much as Cheeta imagines Gormenghast from Titus’s delirious descriptions. The cast of the masquerade have all been instructed in the plot of the previous novels, in the intimate details of the characters’ lives and deaths and proclivities. And giant puppets have been created to represent the Countess, Fuschia, Steerpike, Sepulchre, and others. Titus is brought blindfolded to the event and nearly driven insane as everyone plays their part, as the puppet caricatures act out their love for him, decry his failure to save them, and ask why he abandoned Gormenghast. The helmeted men arrive and capture Titus. Muzzlehatch appears yet again to save him. And at the same time, Muzzlehatch reveals that he has recently blown up Cheeta’s father’s factory (“where, like drones, men worked in praise of death” (186)), and he confronts and murders her father—an emotionless, calculating, skull-headed stand-in for the capitalist class and its exploitation of laborers. And ultimately Muzzlehatch sacrifices himself so that Titus can get free.

And so Titus does. Driven nearly insane, doubting himself, having hurt everyone around him, and with his memories made mockery, played as a grotesque masquerade, Titus ventures out into the wilderness again. In the final pages he comes across a boulder—he has been here before, in Gormenghast, on one of his rebellious forays into the forest. He knows that, with just a few more steps, the walls and towers of the castle would shift into view. And in this moment, with his memory and identity reassured, he decides it is not time to return to Gormenghast, for just to know that it is real—that he is real—is enough:

His heart beat out more rapidly, for something was growing…some kind of knowledge. A thrill of the brain. A synthesis. For Titus was recognizing in a flash of retrospect that a new phase of which he was only half aware, had been reached. It was a sense of maturity, almost of fulfillment. He had no longer any need for home, for he carried his Gormenghast within him. All that he sought was jostling within himself. He had grown up. What a boy had set out to seek a man had found, found by the act of living. (284, ellipsis in original)

And so Titus leaves, running down a new path, “another that he had never known before” and “he drew away from Gormenghast Mountain, and from everything that belonged to his home” (284).

The third novel thus ends with a very similar revelation to that of Gormenghast: Titus does not need Gormenghast, he has learned enough about himself and who he is in order to be a man, to be free. It’s an interesting re-treading of the same theme that ends Gormenghast, but with a slight twist, because Titus Alone seeks to undo all of the self-assurety of meaning, identity, and purpose that Titus built in the previous novel and that convinced him in the first place to turn traitor and leave behind the earldom. Faced with the world beyond, with a fundamental challenge to his being by people for whom his life’s story seems merely to be a fantasy, at worst a dangerous delusion, Titus could no longer hold on to his newfound freedom and surety of being. For being, for Titus, is tied to his history and memory, which the outer world had given him serious cause to doubt. The sight of the boulder, the acknowledgment in physical form that Gormenghast is real, that his memories are tethered to an actual place, this gives him what he needs to stand against the dehumanizations of modernity.

The Problem of Modernity; Or, Why Titus Alone Is Difficult

This, to me, is the most generous way of reading the novel’s conclusion. Ultimately, I don’t like a narrative that seeks to showcase the dehumanizing forces of modernity by turning people into cruel, paranoid shells, who hurt everyone around them and leave death and sadness in their wake. Not to mention the rampant misogyny that follows from Titus’s dehumanization of others in order to retain some sense of his own self. If anything, this aspect of Titus’s character reads as reactionary, not liberatory. Though, thankfully, this reactionary selfishness is counterbalanced by the anarchist, factory-exploding, capitalist-killing figure of Muzzlehatch; he is, after all, the only seemingly moral force in the novel, a figure who recognizes his responsibility to both human and non-human life, who can understand Titus’s abuses for what they are: the reactions of a desperate, strained mind lashing out in self-defense. Of course, I understand Titus’s narrative as a response, among many possible ones, to the problem or conditions of modernity, even if I don’t find this response compelling, much in the same way that I don’t find, say, Catcher in the Rye to be a compelling response to the conditions of its production.

Considered in light of my earlier readings of Titus Groan and Gormenghast, Titus Alone might at first seem to stray from the clarity of Peake’s antiauthoritarian vision. This third novel loses some of the force behind Titus’s rejection of authority and embrace of freedom (in an anarchist sense) that characterizes the culmination of the previous two novels in the conclusion of Gormenghast. But—to be a generous reader—that would seem to be key to what Peake wants to do with Titus Alone. Perhaps, in the shadow of the Gothic, fantastic, impossible Gormenghast, through the symbolic affordances of its hulking, sprawling allegories, decisions to define oneself and to reject authority are made possible. Rejecting the Ritual and the Law are legible, in other words, in the world of Titus Groan and Gormenghast. Indeed, making such antiauthoritarian rejection possible would seem to be the point of it all. But what about in the “real” world—or at least in its Orwellian approximation brought to terrifying life in the city? Here is where the major differences between Titus Alone and the previous novels might take on useful critical significance, since Peake’s approach to narrative and world in Titus Alone radically alter how the text understands and constructs its reality and, by extension, the chief target of this novel’s critical drive: modernity.

In Titus Alone, Peake has succeeded in creating a story that is so estranging as to be off-putting. Where Titus Groan and Gormenghast can be a great pleasure to read, proffering the almost comforting opportunity to get lost in the halls of Peake’s pleasantly interminable descriptions and theatrical scenes, Titus Alone is so shockingly different. There is an unceasing whatthefuckness to the narrative’s movement and pacing—which bandies about from place to place with abandon, lingering here and there before taking off erratically—as well as to the places Titus explores, the people he meets, the situations they live in and actions they take. Where Peake’s efforts at verisimilitude of the utterly fantastic Gormenghast and its grotesque inhabitants are fundamental to the estranging quality of the first two novels, and are indeed central to its fantasy, as Farah Mendlesohn convincingly argues in the essay “Peake and the Fuzzy Set of Fantasy” (collected in Miracle Enough, edited by G. Peter Winnington), it’s the utter whatthefuckery of Titus Alone that estranges, wholly defamiliarizing the reader from any semblance of verisimilitude in the world of the text. It’s unsurprising, then, that when the narrative ventures into the Under-River, the sewer home of “the failures of the earth” (156)[1], and the space most resembling the physicality and atmosphere of Gormenghast, that here Peake reaches for the poetically descriptive, giving us several chapters (chs. 48–61) that feel more like Titus Groan and Gormenghast than anything else in Titus Alone; here, Peake takes us stylistically and tonally “home.”

A fellow Peake reader on Bluesky suggested to me that one difficulty with Titus Alone is that Peake does not handle modernity well, compared to, say, how he conjures the Gothic, grotesque absurdity of the first two novels. In many ways, this is true, but not, I think, because Peake doesn’t know how to write about cars and highways and British urban life—its obscene wealth juxtaposed by deep, devastating poverty. Instead, I think Peake does not handle modernity well, at the mimetic level, because for Peake and other surrealists, for some modernists, and for most of the (proto-)postmodernists, modernity cannot be handled well. Take, for example, Shirley Jackson’s observation in the opening sentence of The Haunting of Hill Houses that “No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality,” where she substitutes what I’m here calling “modernity” for “reality.” Representing the modern world (or, really, a semi-futuristic surveillance state world) as completely ungraspable, as unintelligible in some fundamental way, seems to be the driving point of Titus Alone. For Titus knows nothing of this modern, outer world of plastic and police, of love and sex, of cars and factories and death camps.

There is all the obscenity of Gormenghast itself in Peake’s vision of modernity in the city, but none of the awe reserved for the castle. Where the world of Gormenghast felt whole, where Titus and others—though eccentric freaks—acted as though they lived in a finished, total world, here in the unnameable city, the facade of the castle’s pocket universe reality crumbles. In Peake’s city and its surrounds there is little there there for us, or Titus, to comprehend. We have only the occasional tether to something we can grasp and recognize: Aha, a car! And yet, an impossibly described car, driven in an impossible way, gurgling and screeching like an alive thing, and which Muzzlehatch tethers to a hitching post like an unruly horse. So, a car, indeed? For Titus, his only points of connection to reality in the kaleidoscopic unintelligibility of the modern world are the people who sustain, care for, even hate him. And for this he lashes out at them, recognizing that, though they are his only connection to the realness of this otherwise unreal world, they cannot perceive him as he (thinks he) is: as a son of Gormenghast.

I cannot claim to be as contrarian as I hoped and say that I liked Titus Alone, but damn is it doing something—and with a force of artistic and critical purpose that would seem to defy our ideas about Peake and how his health affected his writing. As Gilmore reminded us—with reference to Titus Awakes, though I think we can extend the sentiment to Titus Alone—Peake tortured this world into life despite the challenges to his brain and body. Peake, at the end of his creative life, offers in Titus Groan a striking, daunting, and often off-putting critique of modernity, of what it means to live in a postwar, capitalist world.

What’s striking to me, in reading through some of the scholarship on Peake and the Gormenghast novels, is how little engagement Titus Alone gets, as though it’s some completely separate thing, unrelated, a failure of a novel, best forgotten, a poor continuation of a critically acclaimed series. But Titus Alone, despite its stylistic differences to the previous novels, is a productively different continuation of Peake’s literary vision and a poignant extension of his critical project. Yes, Titus Alone muddies the waters of Peake’s antiauthoritarian critique in some ways, namely through Titus’s character and narrative trajectory described above, which turn to uncomfortable places, but the novel also clarifies and expands Peake’s critique in others by engaging with modernity, the state, and capitalism in much more explicit language than was possible in the more allegorical narrative of Titus Groan and Gormenghast. Think of the Black Rose and the harrowing description of the death camps she somehow survived, as just one example of Peake’s response to his own experience of modernity and the violence of the state.

Parting Thoughts

Titus Alone concludes the third trilogy in Ballantine’s trilogy of fantasy trilogies in the run up to the BAF series, which by October of 1968, when all three Gormenghast novels were released at once, must surely have been in the planning stages. Taken together, Tolkien, Eddison, and Peake demonstrated an astounding range of possibilities between them for the emergent genre of fantasy as Ballantine charged toward the launch of BAF, suggesting just how excitingly political, artistically diverse, and literarily strong the genre could be, as well as the breadth of cultural and artistic inheritances it might draw on.

Peake’s Gormenghast series in particular spoke to a radical tradition of fantasy that James Gifford has helpfully charted and which, as Michael Moorcock’s anarchist reception of the series shows, found resonance in the countercultural currents of the late 1960s. More than that, I would argue that Titus Alone spoke to an emerging postmodern sensibility when it was republished in 1968 and underlined the idea that postwar, Cold War, late capitalist modernity—the era of Buffalo Springfield’s “There’s something happening here / What it is ain’t exactly clear”—was in some sense fundamentally unknowable, characterized by the unanswerable whatthefuckness expressed in Peake’s final novel. What might have been a tough pill to swallow for late-1950s England found new outlets and energies with Titus Alone’s recirculation in Ballantine’s popular mass market paperback edition.

The potentiality of fantasy, all that it could be, informed by but growing out of what had come before, is the promise of Ballantine Adult Fantasy and what makes this reread project so exciting. And between Titus Alone and the launch of the series proper lie even stranger genre pastures. The next entry in the series, David Lindsay’s philosophical scientific romance A Voyage to Arcturus (1920), just might be the strangest yet.

To get notifications about new essays like this one sent directly to your inbox, consider subscribing to Genre Fantasies for free:

Footnotes

[1] Peake gives us a thorough, eccentric list of “the failures of the earth,” “the great conclave of the displaced,” offering a revealing glimpse into the logic of “failure” in midcentury Britain:

The beggars, the harlots, the cheats, the refugees, the scatterlings, the wasters, the loafers, the bohemians, the black sheep, the chaff, the poets, the riffraff, the small fry, the misfits, the conversationalists, the human oysters, the vermin, the innocent, the snobs and the men of straw, the pariahs, the outcasts, the ragpickers, the rascals, the rakehells, the fallen angels, the sad-dogs, the castaways, the prodigals, the defaulters, the dreamers, the scum of the earth. (156)

Believe it or not, today’s Guardian cryptic crossword contained the clue “Third part of Gormenghast missing from book shelf (5)”.

I can’t defend Titus Alone, but I love the kaleidoscopic invention of it. Titus’ ferality–sort of a combination of Ahab and John the Savage–does get wearying, though. And the misogyny.

Are you planning to read the unofficial Part 4, “Boy in Darkness”? Not in the Ballantine AF series, but not a long detour as it’s a novella.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ha, what timing from the Guardian (or me)!

And I’m not planning to read “Boy in Darkness” anytime soon, but it was collected in a volume (Sometime, Never) with stories by William Golding and John Wyndham that Ballantine published way back in 1957 and then re-released with a Gervasio Gallardo cover in 1971. It wasn’t a BAF title at that time, but Gallardo illustrated a lot of BAF books, so I imagine folks would have thought of it as related in some way.

LikeLike