The Weirwoods by Thomas Burnett Swann. Ace Books, 1967.

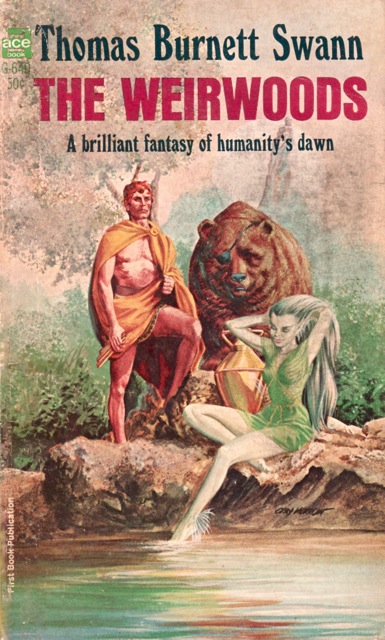

From left to right: Ace cover by Gray Morrow (1967), Ace cover by Stephen Hickman (1977). Both courtesy of ISFDB.

When Thomas Burnett Swann died from a lengthy bout of cancer, he had published sixteen novels in eleven years—well, technically four of those were posthumous, published after his death in May 1976. He was prolific and, in spite of his prolificness, incredibly talented. It helped that he had something of a formula, or at least a vision for his fiction, focusing on what he later called the “prehumans,” or non-human mythical beings, like Dryads, Centaurs, Fauns, who find themselves in increasing conflict with human civilizations sprouting up around the Great Green Sea (the prehumans’ epithet for the Mediterranean). Swann’s novels presented the prehumans as tragic figures of nature falling victim to the rise of civilization and all its attendant horrors. And his novels regularly featured queer characters, love triangles, and a strong concern with the nature and expression of love—romantic, familial, and fraternal.

The Weirwoods was Thomas Burnett Swann’s second novel and possesses many of Swann’s regular interests and some of his best qualities, especially in the novel’s denouement. But as an early novel in his voluminous output, and like his first one, Day of the Minotaur (1966), The Weirwoods evidences a writer still working things out. In many ways it’s a poorer novel than his first. It’s more winding in plot, occasionally awkward in characterization, and Swann fumbles several moments of temporal progression in the narrative that make for jarring, head-scratching sequences. And yet the final fifth of the novel is simply magnificent, easily as strong, achingly beautiful, and tragically powerful (if not as politically poignant) as what Swann thought (and I agree) was his best novel, Lady of the Bees (1976).

Like Day of the Minotaur, The Weirwoods was first serialized in two lengthy installments under Kyril Bonfiglioli’s editorship in the UK magazine Science Fantasy in October and November 1965. As I noted in my essay on Day of the Minotaur, Swann was a highly regarded writer in the UK sff scene of the mid-to-late 1960s thanks to Science Fantasy and in the US he owed much to Donald Wollheim—first at Ace and then DAW—for giving his novels a home. Ace published The Weirwoods as a mass market paperback novel in 1967 with few changes from the Science Fantasy installments and again assigned Gray Morrow to paint the cover. Frankly, I think it’s an ugly and rather lifeless cover, the figures almost randomly presented, even if the expressionistic textures of the background and the colors in the water are stunning. Stranger is the 1977 Ace reprint cover by Stephen Hickman, which is both more beautiful than Morrow’s, with its wonderfully lurid colors, and yet worse as a representation of the novel, since Hickman’s painting has nothing to do with the narrative: there are no blondes, soaring towers, or pegasi in The Weirwoods. Swann was perpetually ill-served by his cover art. And the 1967 cover tagline doesn’t do his novel justice either: “A brilliant fantasy of humanity’s dawn” is printed just below the title, and I again weep for the fact that no one doing Swann’s marketing copy seems to have ever read his books. At least Morrow knew what the characters looked like!

The Weirwoods is set later than most of Swann’s ancient historical fantasies, ending just after Lucius Junius Brutus (pseudo-mythically) led a rebellion to oust the seventh Etruscan king of Rome, Tarquinius Superbus (Tarquin, in the novel), leading to the establishment of the Roman Republic in c. 509 BCE. This is, however, a peripheral event referenced only at the novel’s close, when the newly freed Rome is heralded as a site of future possibility for the novel’s characters in the wake of cascading tragedies and social transformations. (Rome as a site of future possibility is vociferously challenged, as I’ve argued, in Swann’s 1976 novel Lady of the Bees.) The Weirwoods is set in Etruria, in the city-state of Sutrium, one of several cities that formed the federation of city-states populated by the Etruscans, a Paleo-European people who lived in central Italy prior to the coming of the Indo-Europeans but who were strongly influenced by post-Bronze Age Hellenism, who were known across the Mediterranean as expert traders, and who later strongly influenced the Romans (in no small part because they ruled the Romans prior to Brutus’s rebellion). Rome, in The Weirwoods, is a periphery—something yet to become the Rome we know, a place fit only to take slaves from—and as in Day of the Minotaur, when Minoan civilization is waning in the face of the Akhaioi just as the Beasts are waning under pressure from human civilization, so we find ourselves in a world where the Beasts—here called Weir Ones—are poised to disappear just as the Etruscans will.

Swann was deeply familiar with the Classical world of the ancient Mediterranean, as he traveled widely in Italy and Greece in the 1950s, and his dissertation and first academic book focused on Classical influences on modernism, especially in the work of H.D. The Weirwoods bares the imprint of Swann’s deep and broad knowledge of the Greco-Roman (and earlier) past. More than in other of his novels, Swann interweaves in The Weirwoods a great many references to Classical myths, especially more obscure ones, and he also uses the Etruscan names for their gods—Vanth, Sethlans, Turan, Maris, Tages, Uni, Tinia—and emphasizes both their pantheonic similarities to Greco-Roman gods but also their differences. This practice of drawing on older, more archaic, and not the later Hellenistic or Imperial Roman interpretations of myths, while putting his own spin on them, is one of Swann’s great worldbuilding techniques. Swann also emphasizes the cosmopolitan nature of the ancient world and textures his own historical fantasy with characters’ knowledge of the many trade and political associations between Etruria and the rest of the Mediterranean world, stretching even as far east as Persia (with references to Zoroastrianism).

As an aside: I appreciate that Swann changes the referents for the prehumans across his novels. One could assume it’s because he simply had not settled on the right word, though I don’t think “prehuman” appears in any of his novels, and he certainly doesn’t use the term in his final novels from 1976–1977. Notably, the word and the ideas baked into “prehuman” presupposes a modern orientation to ideas of humanness and time that is not present for his ancient characters. Their world, after all, was already ancient, and characters in The Weirwoods point backward in time to older cultures: the Egyptians, Babylonians, and even the pre-Etruscan archaeological Terremare culture (115). We might read the changing referents—Beasts, Weir Ones, Forest Folk (in Lady of the Bees), to name three—to the mythic people of the ancient world as Swann’s way of indicating how different cultures, peoples, and times interact with these beings in their own ways, as well as how the prehumans’ understandings of themselves and their relationship to humanity changes, too. Though there continue to be Dryads, Centaurs, Fauns, and much more across the temporal and spatial range of Swann’s fantasy-historical ancient Mediterranean and its social worlds, who they are and how they act are not static. The Weirwoods underscores this in Vegoia’s story—a being with no heart finds that she has one and that it can beat, even if she dies when this change comes upon her. The prehuman world is dying, Swann tells us with each new novel, anchoring us in a new place and time, repeating ever again the tragedy of history: now is the time of monsters—the rise of civilization.

The plot of The Weirwoods is relatively simple, but contains pleasant depths, even if Swann’s handling of narrative voice and perspective occasionally leave something to be desired. Tanaquil is, after Swann’s fashion (he was obsessed with classic Hollywood’s starlets), the beautiful and bodacious raven-haired daughter of a rich and powerful Etruscan warrior, Lars Velcha (possibly based on a real Larth Velcha, owner of the Tomb of the Shields; the -th ending on Larth was Etruscan, but Latin speakers found /θ/ distasteful and changed it to /s/, and Swann—or possibly an editor—opted for the Latinate spelling Lars). Tanaquil’s mother and brother were recently killed in a raid by Gauls and she and Lars start the novel in the middle of moving to Sutrium for a fresh start. On the way, their caravan passes through the titular Weirwoods. Like the Forest of the Beasts in Day of the Minotaur, the Weirwoods is a haven for the remnants of the once populous Weir Ones, who in this novel are limited to the Centaurs, Fauns, Water Sprites, and bee-like Corn Sprites (they are distinct from Day of the Minotaur’s Thriae). Like the Beasts of Crete, the Weir Ones of Etruria are feared and hated by the Sutrii, but they are tolerated by an ancient, mutual compact that grants the Weir Ones entry into the city to trade goods every ninth day in return for allowing the Sutrii to pass through the Weirwoods to the northern Etruscan cities.

While traveling through the Weirwoods, Lars breaks the compact, leaves the road in search of a stream of water, and on seeing a Water Sprite decides to capture and enslave him in order to cheer up Tanaquil. What a great guy, huh? But Tanaquil has no interest in the Water Sprite Vel—who looks like a teenage boy but is really almost 30—and so he becomes a kitchen slave. As time passes, though, Tanaquil becomes sexually curious about Vel, whose lithesome, perpetually moist body entices her, though she is also repulsed by his ardent (and hateful) lust for her. The Etruscans, we learn, are a decidedly sexual people who enjoy bawdy jokes and aren’t too precious about women’s virginity, so long as the woman is sleeping with a man of equal station. But Tanaquil is, like Thea in Day of the Minotaur, surprisingly chaste among her people—and her sexual awakening, again like Thea, will be driven by changing life circumstances wrought by conflict between humans and non-humans, with the Weir Ones presenting her with a freer, queerer, and less patriarchal vision of sexuality.

The conflict between forest and city begun by Lars, when he stole and enslaved Vel, gains momentum with the arrival in Sutrium of a traveling minstrel or histrion named Arnth, a half-Gaul manly man who is so beautiful and so muscularly sculpted that Vel imagines him to be a god. This character type of a brawny, divinely beautiful man is another Swann mainstay. Arnth is a loner, aside from the eye-patch-wearing bear Ursus (inventive…) who pulls his wagon, but he is also supremely joyful and the moral heart of the novel. He trades some performances for a night’s lodging in the Velcha household and makes friends with Tanaquil but chides her for keeping a Water Sprite as a slave. (He also doesn’t like human slavery, but finds the enslavement of a Weir One to be particularly egregious, unnatural even.) Tanaquil pleads innocence—she didn’t want him for a slave—and impotence—she can’t do anything now that he’s enslaved, for the Etruscans (according to Swann) don’t release their slaves, but Arnth assures her that she is nonetheless partly to blame and that it is her duty to aid in Vel’s escape. With the assurance that Tanaquil will help, if he can arrange it, Arnth journeys into the Weirwoods to find Vegoia, a powerful sorceress among the Water Sprites.

The ethereally beautiful Vegoia is yet another of Swann’s regular character types: the tragic, powerful, and much-respected prehuman woman who falls in love with a human and, for that love, ultimately dies. Swann describes the Water Sprites as “[g]ay, idyllic, and amorous” (37), a people whose carefree attitude and freedom with sex and sexuality owes to their lack of a physical heart, making them a fundamentally different kind of being to humans. Vegoia later explains that their creator deity, the Great Builder, “The Power who made the gods” (53) and the entire universe—and who seems to be an allusion to the Jewish Adonai—made the world in seven days, crafting the Water Sprites at the end of the fifth, after the birds, reptiles, and mammals. The Builder, tired from these exertions and with his mind occupied by thoughts of making humans on the sixth day, simply “forgot to finish us; forgot to give us hearts” (53). It’s a strange detail not repeated, as far as I’m aware, in Swann’s other work, and there is no suggestion here that the other Weir Ones are without hearts, since the “us” and “we” in Vegoia’s speech are specific to the Water Sprites. I could venture that their literal heartlessness makes Water Sprites more akin to nature than the human (as far as Swann sets up these distinctions), but animals have hearts and are clearly natural, as the novel’s cats are. Rather, the lack of a heart seems mostly meant for a metaphorical reading of Vegoia and Vel specifically and to afford the novels’ final, tragic payoffs.

Vegoia rescues Vel, in the end, by using the magic of Cat’s Eye gemstones—the eyes of mummified cats, gifted to the Water Sprites by Egyptians who ventured to Etruria long before the Etruscans arrived and gave it that name—to give Vel the temporary power to converse with Sutrium’s many cats, mostly domesticated servals, who are imports from Egypt and Libya and are described liberally throughout the text. Vel directs the cats to throw off the chains of their captors, Sutrium’s rich Etruscans, and to free themselves. And they do, murdering many of the city’s free citizens in the course of a night. When the sun rises, the human slaves of the Etruscan masters realize that their freedom is at hand and they begin murdering the remaining citizens who survived the cats. At the same time, the Centaurs and Fauns, alerted to the situation in Sutrium, storm the city that has shunned them and join in the murderous festivities. Together, the slaves and Weir Ones fend off Etruscan armies from nearby cities who have come to crush their rebellion, which the Etruscans see as a perversion of the proper order of things. Tanaquil, Vel, Vegoia, and Arnth escape into the Weirwoods and pass the remainder of the novel—the last 30 pages or so—living in the Waters Sprites’s paradisiacal Town of Walking Towers, a lakeside village of stilt-houses.

Here, the novel turns from the plot-heavy back-and-forth adventures focused on Arnth and Tanaquil, who anchor the narrative perspectives in The Weirwoods (and in third person, a rarity for Swann), to a more poetic mode that shifts focus to the complexities of love, grief, and questions of belonging. Where I found the first hundred pages of the novel a little ponderous, the seeds subtly planted by Swann suddenly bloom into brilliance in the novel’s emotionally powerful denouement. And here Swann’s fiction also resonates surprisingly with popular fantasy today; I have a feeling that the romantasy girlies would probably enjoy Swann’s novels—and, if you’re reading this, and romantasy or at least romance/sex in your fantasy is Your Thing: know that Swann includes multiple erotic scenes rendered in beautiful, tasteful detail.

Most of the final fifth of the novel concerns a love triangle: Tanaquil has recognized that her interest in Vel was only lust, that Vel is not someone who can or would love her back and therefore not someone she can love—but Arnth is, and by the time they depart Sutrium for the Weirwoods, she is utterly yearning for the red-headed himbo. But Arnth sees Tanaquil as a sister, for now, and is madly in love with Vegoia, and she with him. So strong is their love, that though the Builder forgot to give Water Sprites hearts, one begins to beat in Vegoia’s chest anyway, and for the unnaturalness of this, she sickens—becoming

a woman with pain-haunted eyes and the pallor of January. Her beauty was undiminished, but she was beautiful in the way of frost on the bronze-green leaves of a cypress tree, or an albatross on a sunless afternoon, suspended between the clouds and a tarpon-colored sea (115)

—and she dies. But before she dies, not wanting Arnth to return to a listless life of wandering, Vegoia shows how Arnth and Tanaquil’s own love might become a refuge for them both:

“Hush,” [Vegoia] said. “Hush, my dear, and love me,” and stabbed [Arnth] to knowledge of her fragile mortality. “I am neither Phoenician glass nor Athenian pottery,” she had said [during an earlier sexual encounter], but he felt that the touch of his fingers might shatter her into a thousand fragments, a thousand iridescences lost in the hands of the rainbow or the sky various with stars. Felt as if words and imperfect gropings of flesh no longer possessed her; as if he could speak and touch, and yet the essential part of her would slip irretrievably beyond his grasp; burst and dissolve on the air like a vial of sandarac.

“You’re going away from me,” he said.

She pressed an icy hand against his cheek. “Listen to me, Arnth. Listen to poor, thin words and understand them as if they were luminous. You know how the hunters build a fire in the woods on a winter day. Their hands are numb with holding their bows and nets; they envy the beasts in their deep-dug nests. Then, the fire leaps up like the walls of a Corn Sprite’s house—yellow and red and orange, and most of all amber. And smoke, not coarse and black, but blue and dusky against the winter sky. Amber fire and blue smoke. And the hunters are warmed. Richly. Not only their bodies. Shall they reproach the fire when it dies to embers? Or the smoke, when it thins and fades above the sere trees? A woodfire was never meant to be enduring.

“There is a second kind of fire. A hearthfire, which burns with a low, pale flame and little smoke, but burns all winter, fed each day and tended by careful hands. In the best of worlds, woodfires and hearthfires would make a single flame of rich colors burning always. Perhaps the best of worlds is the Elysium which lies beyond the demon-haunted cliffs and the dark Styx. Perhaps, but here, it is not so. And it is the measure of a man that he can move from woodfire to hearthfire without bitterness, without reproaching the gods, his enemies, or himself. Let him remember, if he will, the blue and the amber, but not with regrets for what he has lost; rather, with gratitude for what he has found: a brief, bright burning in a wintry forest.”

He took her in his arms. “Why do you speak in riddles? Woodfires. Hearthfires. I am your fire, Vegoia! Warm yourself in my arms!”

“Forgive me if I have puzzled you. I am only saying that the human heart—from what I have seen of hearts—was not intended to poise always in the flush of worship, like a devotee standing in front of a temple. There are cottages as well as temples. The heart must rest, my dear. Now you must leave me and return to the lake.” (118–119)

Sending him away, Vegoia dies and is brought to the Weir Ones’s underworld, but not before bidding a final goodbye to Arnth as a ghost. And the novel ends, with Vel having died tragically of his own hatred, with Vegoia dead from a kind of love she was never meant to feel, and with Arnth and Tanaquil returning together to the human world, heading to a Rome newly freed from its Etruscan kings—and they go into this world as lovers gathered at a newly kindled hearthfire, lit by the dying embers of a woodfire. It may be excessive to quote Swann so lengthily, but this is really only a drop in the bucket of the artful and affecting prose that energizes the final fifth of The Weirwoods, and it shows not only his emotional brilliance as a writer but also his ability to weave in powerful and tasteful metaphors, and the weighty tragedy of his narrative.

These final scenes between Arnth, Vegoia, and Tanaquil turn away from what, for most of the novel, reads like a decidedly sexist vision of romance, with Arnth philosophizing about how women are a “net” that captures men with their feminine wiles, how sex can never just be sex, how every woman’s interest in a man obscures their desire for marriage and to settle down, and so on—when all a man really needs is the open road, an audience for his music, and a one-eyed bear for a companion. There are undertones here of both a homoerotic fear of heterosexuality (Arnth is a virgin for fear of women’s entrapping sexuality) and a patriarchal rejection of women as giving value to men’s lives, which is itself a bit queer.

I found this treatment of romantic gender relations initially quite frustrating, but Swann balances out Arnth’s bro code in several ways. First, with Vel’s queer—but not necessarily sexual—desire for Arnth, who gives Vel such ecstatic joy through music that, when Arnth forsakes Vel for bringing about so many deaths in Sutrium and finding joy those deaths, Vel imagines a woman—Tanaquil—must be at fault and so tries to kill her (and ends up dying, tragically, himself). Then, Arnth’s bro-y-ness is transformed when he learns to reject his own bro code in favor of one and then another form of love. In the end, Arnth embraces the bondage of the net of (heterosexual) love that he has spent his life running from, afraid that to lay down roots, to devote himself to another person, is to be trapped and to lose his identity (whatever that means). But Vegoia and then Tanaquil show Arnth that love can be a kind of freedom.

As usual, Swann thinks loftily with this short fantasy novel and touches on questions of major moral and social import. The novel’s major themes are common to Swann’s work, but though he treads the same paths regularly, he treads them differently each time, such that each journey into Swann’s historical fantasies is both familiar and wholly new. In The Weirwoods, Swann is concerned again with what we might call a conflict between city and forest or between civilization and nature, the human and the non-human. Within this dialectic conflict, Swann also pursues the theme of freedom by focusing on what it means to be captured, caught in a net, tamed, or enslaved—very different ideas that he weaves together thematically, though the tapestry only takes shape with time—and he focuses on the injustice of captivity as a social and moral failing of the “affluent citizens” (6) who ignore captivity because it is the system which subtends life as they know it. Swann also deals with the question of “nature” in the ontological sense—that is, what we have the capacity to do or not do, to be or not to be, by virtue of what we are: as a human, as a man or woman, as a Water Sprite, as a cat. This is a potentially problematic vision of nature as destiny, and one that Swann no doubt borrows from ancient Greek epic and tragedy. Swann also, as I’ve noted, deals heavily with love, distinguishes it from lust or purely sexual desire, and theorizes its many depths and pleasures.

Swann’s theme of captivity is perhaps the strongest and most obvious in the novel. It extends an idea from Day of the Minotaur—that of Thea trying to “tame” Eunostos the Minotaur, to make him more like a man, to fit him into Minoan tunics and urge him to conform to her vision of Minoan propriety. Swann is very much interested in that idea in The Weirwoods, but comes at it from three angles. One, the idea of (heterosexual) love as a “net” that captures men, I’ve already discussed above. But Swann also addresses both captivity of the non-human by humans and human slavery. These concerns are present from the very beginning, when Swann introduces Sutrium as a “town of affluent citizens, obedient slaves, and pampered cats” (6). Swann names a very specific set of inhabitants that seems at first a merely poetic descriptor of an Etruscan society living luxuriously, “blessed by the gods” (6), served by goodly slaves, and so well-off that even the cats are treated as equal to free humans. Moreover, Swann describes both Tanaquil’s cat Bast and the presence of many other cats, and even the trading routes that brought cats to Etruria from Egypt and Libya (each implying a different social hierarchy of cat ownership; Egyptian cats are “purer”). I thought, at first, this was just quirky; after all, Swann has very particular interests that occur again and again in his fiction, such as his love of cute bears. But the stratification of Etruscan society into a hierarchy of citizens, slaves, and cats is crucial not only to the novel’s plot but to the novel’s larger argument about civilization and freedom.

I’ve given little attention to Tanaquil’s father, Lars, but he is in many ways the antagonist of this novel, despite appearing for only a short time. He, or rather his obedience to an ideology of “might makes right,” sets the entire story in motion. As an elite Etruscan warrior, and a man who “had always been served by slaves, […] it seemed to him right and inevitable that some should rule and some should serve” (12). Guided by this ideology of a naturalized social hierarchy and by the idea of beneficent masters improving the lives of those they enslave merely by having enslaved them, Lars believes it is “really a kindness” to take Vel from the Weirwoods and make him a slave, to “tend him [through forced labor] in the bosom of a pleasant house” (12). This, Swann suggests, is the ideology structuring human civilization and which results in both the fundamental inequality among humans who make up civilization but also the antagonism between civilization and nature, with nature understood as a thing to be captured, tamed, and made fit for a “a pleasant house.” And for this transgression—both for breaking the compact between city and forest, and for enslaving a Weir One; put another way: for taking civilization “too far”—not only Lars but all of Sutrium are punished. First by the cats, urged to take their freedom (and revenge) by Vel; Vegoia clarifies that the cats were not acting under Vel’s authority, but merely making the justice they had been denied for so many years in captivity. Then by the slaves. And lastly by the Weir Ones, who come in from the forest.

Importantly, Vel’s anger—having driven the retributive violence and resulted in the (righteous) death of Tanaquil’s father—is not condemned in the novel. Arnth instead condemns Vel’s orientation to violence, his joy in it, and so decides to break off their friendship. (This leads to Vel’s jealous attempt to murder Tanaquil, and thus his own tragic death.) Vegoia and Arnth understand the “Bacchanalia of freedom” (88) that erupts in Sutrium as just, even as Tanaquil imagines it as almost a second fall of Troy, presaging the fall of Etruria itself. “The world is mad,” she thinks (89). Tanaquil at first views the revolt in purely personal terms: a slight—by individual slaves, owned by her family, and an individual cat, Bast, whom she pampered and loved—against her personally and against her father. But Tanaquil comes to recognize “the truth of the cats and the slaves, the truth of the liberation which follows slavery” (86–87). In a word, Tanaquil comes to see the revolt as a response to structural oppression in which she participated, especially after recoiling from Arnth’s disdain for her callous attitude toward Vel’s enslavement.

In his handling of these two radically different perspectives on the justness of violence against captors and enslavers, Swann cleverly juxtaposes a revolutionary perspective (that of Vegoia and Arnth) with one that is either basely liberal or at worst reactionary, and which speaks through Tanaquil as a possible stand in for the reader. The latter perspective on violence and justice is ultimately left untenable by the argument of Swann’s narrative. And at the same time, by condemning joy in violence but not the violence itself, Swann gestures at the complex moral terrain that arises where justice and violence meet. With its metaphors of capture, nets, and slavery, The Weirwoods is a novel about freedom and what happens when it is denied, how (a certain kind of) justice is gained, just as much as it is about love and grief and how we keep living in the wake of tragedy.

The Weirwoods is certainly not my favorite Swann novel, in large part because it does feel somewhat discombobulated and not as focused as other of his novels, but given that it was only his second novel, it already shows great improvement in his craft as a writer. It’s a somewhat messy book, yes, but in it Swann continues to surface several of his major themes, especially the tragic nature of interpersonal relationships and doomed love, that will become prominent in his writing. The last 25 pages of The Wierwoods are simply magnificent, the first hundred, not so much. It’s almost as if these two sections were written in different periods of Swann’s career, with the final pages reading incredibly mature and like the best of his later fiction, and the first part rather stilted, awkward, less graced by his beautiful prose or eye for powerful emotions, and more focused—sometimes clumsily so—on worldbuilding. Things do come together, and Swann’s thematic purpose is crystal clear by the end, and maybe that’s all that matters. In the end, it works, and at the end it’s beautiful and heart-wrenching, with a final turn toward hope that is also a hallmark of Swann’s novels.

I continue to be amazed by this largely forgotten writer and to lament that his works are not given more attention. It’s my hope that, by lingering on these novels in these essays, I’ll convince a few of you that Swann is the next big (old) thing and that you’ll help me recover him from the moldering great unread of fantasy fiction’s history.

To get notifications about new essays like this one sent directly to your inbox, consider subscribing to Genre Fantasies for free:

13 thoughts on “Reading “The Weirwoods” by Thomas Burnett Swann”