The Mezentian Gate by E.R. Eddison. 1958. Ballantine Books, Apr. 1969. Zimiamvia 3. [My version: 1st printing, Apr. 1969]

This essay is part of Ballantine Adult Fantasy: A Reading Series.

Table of Contents

Returning to Zimiamvia

Reading The Mezentian Gate

Eddison’s Zimiamvian Vision

Parting Thoughts

Returning to Zimiamvia

With this essay we reach the end of the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series’s “preface novels,” as listed by BAF’s “consulting editor” Lin Cater in his book Imaginary Worlds: The Art of Fantasy (1973; BAF 58). And in so doing we also come to the final novel in E.R. Eddison’s Zimiamvia trilogy: The Mezentian Gate. The novel was originally published in 1958 in the UK, 13 years after Eddison’s death in 1945. Like Mervyn Peake’s Titus Alone, Eddison’s final novel was unfinished at the time of his death. Unlike Peake, however, and understandably so given Peake’s deteriorating mental health during the last decade of his life, Eddison left behind copious notes and lengthy chapter outlines for the unfinished novel, along with letters to his brother, Colin, which explain his vision for the novel and its fit—narrative as well as philosophical—with the larger Zimiamvia series.

Ballantine’s mass market paperback printing of The Mezentian Gate was the first American edition of the novel, published in April 1969, one month before the official launch of BAF with Fletcher Pratt’s The Blue Star. Like Peter Beagle’s The Last Unicornand A Fine and Private Place, both published in February 1969, The Mezentian Gate sported “A Ballantine Adult Fantasy” as a genre descriptor in fine print on the front cover. Despite the obvious association of Eddison’s Zimiamvia trilogy—comprising Mistress of Mistresses, A Fish Dinner in Memison, and The Mezentian Gate—with BAF, both as preface novels and in plain fact of being important pre-genre texts in the fantasy tradition Ballantine and Carter were helping to define, the books did not seem to sell well enough to get reprinted as part of the BAF series. Only A Fish Dinner in Memison got another printing during the lifetime of BAF (1969–1974), and likely because it was reprinted without the other two novels alongside it, it made little sense to put the BAF logo on the cover (I’m a little confused as to why the second novel was reprinted then and not the others!). Eddison’s The Worm Ouroboros, however, was reprinted three times during the BAF series’s lifetime and was branded with the BAF logo in its seventh printing. (For a detailed look at the printing history of Eddison’s novels, see Douglas A. Anderson’s phenomenal post on the topic).

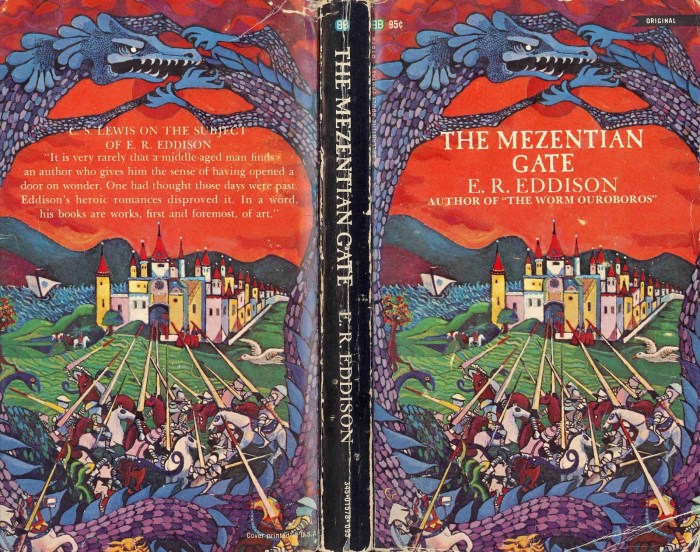

Like the Ballantine editions of Eddison’s novels that came before, The Mezentian Gate was given a cover featuring a dragon eating its own tail as the cover’s frame, with an impressionistic scene of medieval battle raging inside that frame, ostensibly capturing the feel of the novel, though in this case the only thing that stands out as relevant to the novel is the goofily cartoonish lynx. As Anderson notes in the post linked above, this was painted by William Benson in the style of Barbara Remington, artist of the previous Eddison covers, when she proved unavailable. On the back cover—which reduplicates the painting from the front—the copy offers a quote from C.S. Lewis:

It is very rarely that a middle-aged man finds an author who gives him the sense of having opened a door on wonder. One had thought those days were past. Eddison’s heroic romances disproved it. In a word, his books are works, first and foremost, of art.

The front interior copy connects all four of Eddison’s fantasy novels, notably dispensing with the efforts of the earlier novels’ marketing copy to label them a “cycle” or a “trilogy” or some such, and gives a fuller version of Lewis’s blurb. The back interior advertisement then places Eddison’s oeuvre in the larger context of “Great Masterpieces of Adult Fantasy.” The ad lists all of Eddison’s novels, Peake’s Gormenghast books (notably, these are numbered as part of a series, but Eddison’s are not), and David Lindsay’s A Voyage to Arcturus. Oddly, no Beagle. But the ad implores readers to “watch for” Lord Dunsany’s The King of Elfland’s Daughter (BAF 2), William Morris’s The Wood Beyond the World (BAF 3), James Branch Cabell’s The Silver Stallion (BAF 4), and George MacDonald’s Lillith (BAF 5). BAF is coming… but before we get there, we’ve got to talk about The Mezentian Gate.

Reading The Mezentian Gate

I made no secret in my previous essays on the first two novels in the Zimiamvia trilogy, Mistress of Mistresses and A Fish Dinner in Memison, that I do not like those novels. Yes, they are brilliantly written, but they are dull and lifeless books, shot through with a rather inane obsession with Beauty and this very particular idea Eddison has developed about serving Beauty—i.e. Aphrodite: womanhood personified in a single perfect woman, but glimpsed a bit in each woman—as the ultimate goal, the thing to live for, the only thing that has meaning and value. Since Reality is wholly dependent on Her, nothing else matters: not life’s hardships, not the qualms of the masses, nothing but Her and Her desires. It’s dorm-room philosophy dressed up as heroic romance and at least much more erudite and more literarily impressive than perhaps any other author might have made it. I thus absolutely dreaded reading The Mezentian Gate. I expected, perhaps, that with time and distance—with Peake’s trilogy, the novels by Lindsay and Beagle, and Carter’s study of Tolkien as a buffer—I might begin to reappraise the Zimiamvia trilogy, to welcome another go at this world of Eddison’s. But no. I did not.

To be fair, The Mezentian Gate is significantly more interesting that its predecessors in the Zimiamvia trilogy (which I set apart entirely from The Worm Ouroboros, a fascinating novel that I found critically productive). This is for two reasons. The first is that the novel is unfinished and thus, in its published state, complete with copious matter-of-fact notes and chapter-level plot outlines compiled by Eddison himself (rather than having being finished by another hand, posthumously), it is a much more exciting text for the critic to work with—at least to me it is, but that is probably owing to how much I dislike the other two Zimiamvia novels in their fully finished states as well as how much I enjoy books with messy bibliographic histories, e.g. Peake’s Titus Alone. The second is that it’s a novel that is much clearer to purpose; here, Eddison—and by his own admission, in his “Letter of Introduction” to the novel—more skilfully and carefully combines the excessive and drab philosophizing of A Fish Dinner in Memison with the greater emphasis on political machinations that threaten to tear apart Zimiamvia in Mistress of Mistresses. The Mezentian Gate is, in essence, the best of both worlds. Whatever that means when the books it conjoins into a new chimaeric third thing were so unlikable.

The Mezentian Gate was unfinished at the time of Eddison’s sudden death while gardening in August 1945. He had written most of the book during his stint as warden of an Air Raid Precautions office during WWII, years after his retirement from the civil service in 1938 to focus on his writing career (for details of Eddison’s life and thought during WWII, see Joe Young’s 2012 article “Aphrodite on the Home Front”; I’ll engage with this article more thoroughly in the next section). The posthumous publication of The Mezentian Gate in 1958, which was republished by Ballantine in 1969, featured only 14 completed chapters out of 39 planned. In other words, Eddison only completed about 36% of the novel by a simple count of chapters. (The 1992 Dell omnibus edition of the Zimiamvia trilogy includes partial drafts of chapters 8, 12, and 30–33 discovered after the novel’s initial publication.) The other 25 chapters—excepting one, chapter 35, “Diet a Cause”—had been outlined by Eddison, some for several pages, others just a paragraph or two, and these outlines were published as is. The Ballantine edition runs to 270 pages. Of these, the 14 completed chapters comprise 190 pages, while the outlines of the unwritten 25 chapters comprise 80 pages. Assuming that chapter counts are guarantees of relatively stable page counts (they aren’t), such that 190 pages can be said to be roughly 36% of the novel (since 14 chapters is c. 36% of the 39 chapters planned), then using the percentage formula Y/P% = X (i.e. 190/36% = X and solving for X) we could calculate that the fully finished version of The Mezentian Gate would be close to 528 pages. Or roughly the length of The Worm Ouroboros. This is unsurprising, really, since the story in The Mezentian Gate is of huge scope, taking place over decades and serving as a bridge between the events of the previous novels in the trilogy.

To help make sense of the somewhat awkward format of this unfinished novel, The Mezentian Gate included a “Prefatory Note” originally written by Eddison in November 1944 and coincidentally fit to purpose. This was presumably a cover letter for a package that included Eddison’s Argument with Dates—that is, a manuscript containing the chapter outlines that were subsequently published in the posthumous novel. Interestingly, Eddison notes in the close of this letter that “If through misfortune I were to be prevented from finishing this book, I should wish it to be published as it stands, together with the Argument to represent the unwritten parts” (vii). Whether Eddison wrote this because it was wartime or because of concerns about his health, I haven’t been able to tell.

The novel begins with a “Letter of Introduction” that was originally written by Eddison to his brother, Colin, to describe the novel and its philosophy. A Fish Dinner in Memison also opened with “A Letter of Introduction,” this one written to George Rostrevor Hamilton (who played a part in compiling the manuscript of The Mezentian Gate). Since both novels are works of theory fiction, each expressing a critique of moral philosophy in the form of a heroic romance, it made good sense to include some note from the author to serve as a guiding principle to understanding his texts. All the more so because these novels combine Eddison’s idiosyncratic philosophy with an ornate literary style, making the whole a rather abstruse literary experience. Moreover, as Jamie Williamson argues in The Evolution of Modern Fantasy, this textual layering of intention, authority, and critical apparatus into the fantasy novel is a common trope that developed in pre-genre fantasy novels of the nineteenth century and has its origins in the genre’s antiquarianist roots.

The “Letter” that opens The Mezentian Gate is a touchstone for understanding not just this novel, but the whole Zimiamvia project as Eddison understood it by January 1945 (I believe this is the date of the letter, as suggested by Colin’s note about the posthumous publication of the novel, viii). Eddison begins the letter by almost excitedly stating “The trilogy will, as I now foresee, turn to a tetralogy; and the tetralogy probably then […] lead to further growth. For […] the theme itself is inexhaustible” (xi). It’s curious that Eddison, Peake, and Tolkien all thought of their fantasy sagas as in some way unending or unfinished, as part of a larger mythos or, as Tolkien would have it, a “sub-creation,” and that they all kept working on these worlds and their stories until their deaths. And, though it means nothing beyond the mere coincidence of the fact, it’s interesting that both Peake and Eddison died leaving the final book of what became known—by default, after Tolkien, and likely thanks very much to Ballantine’s efforts in this regard—as a trilogy unfinished. Moreover, both authors’ final books were published posthumously and, much later, re-edited to restore the author’s vision. For Eddison, as probably also for Peake and Tolkien, an “inexhaustible theme” kept the fires of his sub-creation burning, opening further vistas onto what could have become the Zimiamvia cycle.

Eddison gives a summary of this “inexhaustible theme” in this “Letter,” quoting Spanish philosopher and cultural critic George Santayana (d. 1952):

The divine beauty is evident, fugitive, impalpable, and homeless in a world of material fact; yet it is unmistakably individual and sufficient unto itself, and although perhaps soon eclipsed is never really extinguished: for it visits time and belongs to eternity. (qtd. xi–xii)

The quote is from Santayana’s 1896 book The Sense of Beauty, which he later called a “wretched potboiler” written solely to get tenure at Harvard. Notably, the book offers a psychological account of aesthetics as a human experience shaped by our senses, rejecting the metaphysical role of the divine but admitting it is a useful metaphor. For Eddison, this limited quote is pitch perfect: Beauty is eternal, it is Perfection, it is the essence of Reality and whatever it is we call the divine. Its home is Zimiamvia, where on account of that world’s perfection, “nobody wants to change it […] apart from a few weak natures”; “there is no malaise of the soul” in Zimiamvia and even the enmities between men are divine (xii). For Eddison, this understanding of Beauty renders in Zimiamvia what we might consider an amoral universe, where terrible things are great deeds and terrible men are worthy of praise and honor, since all things are reflections of the one Truth, of Beauty:

This […] is easier to accept and credit in an ideal world like Zimiamvia than in our training-ground or testing-place where womanish and fearful mankind, individually so often gallant and lovable, in the mass so foolish and unremarkable, mysteriously inhabit, labouring through bog that takes us to the knees, yet sometimes momentarily giving an eye to the lone splendour of the stars. When lions, eagles, and she-wolves are let loose among such weak sheep as for the most part we be, we rightly, for sake of our continuance, attend rather to their claws, maws, and talons than stay to contemplate their magnificence. We forget, in our necessity lest our flesh become their meat, that they too, ideally and sub specie aeternitatis [a Spinozan phrase for “from the perspective of eternity”], have their places […] in the hierarchy of true values. This world of ours, we may reasonably hold, is no place for them, and they no fit citizens for it; but a tedious life, surely, in the heavenly mansions, and small scope for Omnipotence to stretch its powers, were all such great eminent self-pleasuring tyrants to be banned from “yonder starry gallery” and lodged in “the cursed dungeon. (xiii)

Here, in full scope, at the end of his life and in description of the novel he considered “first in order of ripeness” (xiii), Eddison lays out rather clearly his philosophical argument for a universe structured by eternal hierarchies, all of which is in service of demonstrating the power of Omnipotence itself, the final truth of Beauty. Such a vision understands the lot of individuals and everything that happens in our lives as a passing concern, always subsumed to the larger order of things, and only ever, really, manifestations of eternal principles or truths, and therefore never significant in and of themselves. Our world is but a simple training ground, a testing place. Indeed, as The Mezentian Gate makes clear of events that occurred in A Fish Dinner in Memison, our world—what Tolkien would have called the “primary world”—is but the plaything of the gods who abide in Zimiamvia (the ostensible “secondary world”), created in all its complexity for but a half-hour of amusement during a dinner party, before being popped and returned to nothingness by Beauty Herself, Aphrodite in one of her many guises. In Eddison’s novels, the primary and secondary worlds are reversed: we are but the sub-creation.

Like the previous Zimiamvia novels, The Mezentian Gate starts with a preface of sorts, here called the “Praeludium” (cf. the “Overture” of Mistress of Mistresses and the “Induction” of A Fish Dinner in Memison), which offers another (and thankfully final) view of Lessingham’s life. I’ve read several descriptions of the Zimiamvia trilogy that summarize it as the story, essentially, of Lessingham and Mary—and what happens to them when they die, when they ascend to the Elysian Fields of Zimiamvia. Certainly, the fact that each of the novels begins with a vague description of Lessingham’s life, and that A Fish Dinner in Memison goes much further to interweave chapters of Lessingham and Mary’s life on Earth with its Zimiamvian chapters, lends credence to the idea that the trilogy is in some way about Lessingham. But as with The Worm Ouroboros (see the section of Lessingham), Lessingham is the bridge between the world of the reader and that of Zimiamvia, of the fantasy. And as each successive novel in the trilogy makes clearer, pulling us slowly into its revelation of ontological reversal, Lessingham is the fantasy, Zimiamvia the reality. The “Praeludium” to The Mezentian Gate serves as a reminder of what “great eminent self-pleasuring tyrants” should be: men of action, of accomplishment, who climb mountains, who train armies to conquer Paraguay and the Lofoten archipelago, who say “No!” to modernity and reject the transient morality of their age, who possess the will to power, who are, in a word, Übermenschen. But even then, a man such as Lessingham is but a pale reflection of greatness, for his existence is but the temporary avatar of true gods: of Barganax and the even greater Mezentius.

The Mezentian Gate is the third novel in the trilogy, but acts chronologically as the first novel, starting decades before the events of Mistress of Mistresses and serving as the background to the political situation in Zimiamvia at the time of that novel’s opening: namely, how King Mezentius came to die, leaving a succession crisis that threatens to tear the Triple Kingdom of Fingiswold, Rerek, and Meszria apart. The Mezentian Gate also encompasses the events of A Fish Dinner in Memison, awkwardly recapping them and showing their immediate aftermath. In many ways, though, this recapitulation of the events of A Fish Dinner in Memison is surprisingly welcome, since that novel is particularly difficult to parse and the eponymous and immensely pivotal fish dinner clearly needed greater explication—at least I needed the helpful refresher, since I found it incredibly difficult to understand. It’s really only because of The Mezentian Gate that the middle novel makes any sense.

The story of The Mezentian Gate is the history of how the three independent realms of Fingiswold, Rerek, and Meszria came to be combined into one Triple Kingdom under the rule of the kings of Fingiswold. A great deal of this novel, therefore, concerns the political maneuverings between two major dynasties—the kings of Fingiswold and the Parrys of Rerek and Meszria—as they consolidate power in their own lands, with the Parrys ultimately becoming subject to Fingiswold under the young King Mezentius. Parallel to this are events happening in the neighboring kingdom of Akkama, a land of nomads—“a cruel, base and savage people” who speak only “a gibberish of their own” (80)—ruled by exiled nobles from Fingiswold. (The racist descriptions of Akkama mix historical elements of North Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, and the Turkic steppes, suggesting a realm modeled variously on Norman-ruled Malta, Outremer, or the Ottoman empire.) Mezentius forges a single kingdom through shrewd marriages and political alliances, successive conquests of Akkama’s upstart rulers, and his own magnanimous character. Most of this, however, is unwritten and sadly only available in outline form.

The Mezentian Gate is divided into seven “books.” The bulk of the plot outlined above takes place in books II through V. Book VI slows down to focus on growing conflicts within King Mezentius’s inner circle (namely with his wife, Queen Rosma, and his ally Horius Parry—villain of Mistress of Mistresses). And the final book, VII, details again the fish dinner from the previous novel and the aftermath of that dinner, ending, finally, with Mezentius’s revelation that he is himself a divine being, a god, if not God, and his subsequent decision to die (knowingly poisoned by Rosma) in order to see if an omnipotent, omniscient being can in fact die, thereby challenging the order of the universe and perhaps opening up a new reality. This momentous decision by Mezentius—the eponymous Mezentian Gate, beyond which no one but He may pass—is meant to solve a paradox about God. It answers whether an omnipotent being can truly do all things, including what would seem to nullify omnipotence itself. At the end of The Mezentian Gate, then, God is truly dead, and this seemingly proves God’s omnipotence all the more.

As usual, Eddison’s prose in The Mezentian Gate is unsurpassedly beautiful, flowing with the richness of Zimiamvia’s divine realms and creating a world that is bombastically larger than life, exploding with vibrant energy and emotion and wit and intelligence. A choice example can be found at the opening of chapter two:

It was eight months after that meeting in Mornagay: mid-March, and mid-afternoon. Over-early spring was busy upon all that grew or breathed in the lower reaches of the Revarm. Both banks, where the river winds wide between water-meadows, were edged with daffodils; and every fold of the rising ground, where there was shelter from north and east for the airs to dally in and take warmth from the sunshine, held a mistiness of faint rose-colour: crimp-petalled blossomed, with the leaf-buds scarcely as yet beginning to open, of the early plum. Higher in the hillsides pasque-flowers spread their tracery of soft purple petal and golden centre. A little downstream, on a stretch of shingle that lay out from this right bank into the river, a merganser drake and his wife stood preening themselves, beautiful in their whites and bays and iridescent greens. It was here about the high limit of the tides, and from all the marshland with its slowly emptying creeks and slowly enlarging flats (for the ebb was well on its way) of mud and ooze, came the bubbling cascade of notes as curlew answered curlew amid cries innumerable of lesser shore-birds; plover and sandpiper, turnstone and spoonbill and knot and fussy redshank, fainter and fainter down the meanderings of the river to where, high upon crags which rose sudden from water-level to shut out the prospect southwards, two-horned Rialmar sat throned. (18)

This is a truly magnificent passage and we see in it Eddison’s similarities to Tolkien, Peake, and earlier pre-genre fantasy writers who understood landscape—and the artful rendering of it in literary form—to be absolutely integral to making their fantasy worlds, in some sense, real or real-seeming, and a key aspect of the verisimilitude so many fantasy writers use at the same time to denaturalize readers’ from their own world, rendering “reality” in new, critical perspectives. The scene begins with a moment in the changing of the seasons that quietly transitions readers from the big reveal at the end of the first chapter, and from there pulls the reader almost as a camera might move slowly through a forest in the opening scene of a film, lingering on tiny images and small happenings that each seem so delicately real and together prove the hapticity of this fantasy world. Eddison pulls us gently through the landscape, enlivening it with color and temperature and texture, with animal inhabitants, with the sounds of their lives, just enough that we understand what it might be like to be not just in Zimiamvia but here, on the banks of the Revarm river in early spring, until he suddenly shifts our perspective away from this temporary elysium to a lofty mountain rising high above it all—an abode of the gods, the seat of the Fingiswold palace, the birthplace of Mezentius, the god who will do the impossible and die. The book abounds with such powerful imagery, familiarizing us with the impossible, making Zimiamvia more real, perhaps, that reality…

At the same time that Eddison renders unto us this secondary world that is, in fact, meant to be the Reality that our world is but a pale imitation of, he also balances these wonders with a healthy dose of drama. Indeed, when he sets aside his rather dull efforts at theory fiction, Eddison’s sense of the dramatic is impressive. Perhaps the most interesting part of the novel is its first few chapters, where political intrigue abound around the question of who killed King Mardanus and why, of why the widowed Queen Stateira marries the foreign, exiled prince of Akkama, Aktor, and why Aktor suddenly commits suicide nearly two decades later, when his stepson King Mezentius comes of age. Aktor is perhaps the most compelling character in the novel, an eminently tragic figure in the vein of the Goblin Lord Gro in The Worm Ouroboros. Here, Eddison’s admiration for seventeenth-century English drama comes to the fore in wonderfully dark, contemplative ways. Aktor’s short-lived story arc is all Shakespearean tragedy, a mixture of Macbeth and Othello, but there’s far too little of this affect, unfortunately, in the manuscript as we have it. And as with the preceding Zimiamvia novels, Eddison turns overly much of his attention instead to a gallery of largely interchangeable personalities, all drab and characterless (yes, even and especially the principle characters, Mezentius, Barganax, and Fiorinda; Rosma might be the one stand out, but most of her story is told in the outlines), and to lengthy, plodding conversations about Beauty and Reality.

It’s clear from what Eddison wrote first, what he left behind as finished text, where his main interests lay. He wrote all of book I—which sets up the Parrys’ squabbling for power in Rerek and Meszria, as well as the death of King Mardanus, his betrayal by Aktor, and the remarriage of Queen Stateira to Aktor—, a single chapter in book II—which is about divine power—, two heavily philosophical chapters in book VI that are highly reminiscent of A Fish Dinner in Memison, and all of the final book, where he expands on and clarifies the philosophical content of the previous novel’s fish dinner and brings everything to its rousing conclusion. Clearly, for Eddison, what his novels were doing at a philosophical level, as works that offered a unique vision of moral philosophy, aesthetics, and perhaps even theology, was at the forefront of how he understood his work as a writer and the value of his novels.

Eddison’s Zimiamvian Vision

What, then, is The Mezentian Gate and by extension the Zimiamvia trilogy about? What is Eddison’s vision for his fantasy series? The answer is multifaceted and complex. Indeed, Eddison’s own writings about his series give answers that are difficult to parse, densely populated with references to philosophers like Baruch Spinoza and George Santayana, among others, and which circle around these lofty ideas about Beauty and Reality and Perfection. I’ve tried to parse some of what Eddison is up to in my essays on Mistress of Mistresses and A Fish Dinner in Memison, but I want to go a bit deeper in this essay on The Mezentian Gate since this is probably my last foray into Eddison’s Zimiamvia unless someone quite literally forces me to read these three novels again (I’d reread The Worm Ouroboros, no problem). I want to leave Eddison with a strong understanding of his ethos and philosophy, and a better grasp on what he wanted from this series that responded to his “inexhaustible theme.”

For such an established name in fantasy, and one who was marketed as having been influential on both Lewis and Tolkien, among others, there is surprisingly little scholarship on Eddison. True, his books have been much harder to find, sometimes going a decade or more without a new printing, and they are certainly more demanding reads than any of the other writers of pre-genre fantasy. Perhaps, too, their particular philosophical focus has confounded or simply turned off fantasy scholars, as it has me. There is, indeed, little in the Zimiamvia books that commend themselves to a reparative reading—though their very peculiar gender politics need attention!—and there is a great deal in them that smacks of fascism. But this is precisely what makes Eddison’s writing fascinating to me, especially given the long-standing critiques, often leveled by scholars who read very little fantasy, that the genre is at its core, perhaps in its very form (as many Marxist critics would—wrongly—argue), conservative and reactionary. My own approach to genre, as I’ve laid out elsewhere on this blog (see, for example, this section of my essay on Gormenghast), is that forms do not have inherent politics, but texts do, and how they express those politics through the formal affordances of genre is paramount to understanding how authors and readers use fantasy.

I’ve noted before that Anna Vaninskaya’s Fantasies of Time and Death: Dunsany, Eddison, Tolkien (Palgrave, 2020) is an important starting point for anyone who wants to understand Eddison’s Zimiamvia trilogy better. It is an unsurpassed, not to mention wonderfully written, study of Eddison’s writing—but it is also hyper specific and thus limited in putting Eddison in cultural and historical contexts. I want to turn, then, to Joe Young’s 2012 article, “Aphrodite on the Home Front: E.R. Eddison and World War II,” which offers a study of the Zimiamvia novels focused explicitly on their politics, philosophy, and what Eddison himself said about them. Importantly, Young’s article draws on archival materials, mainly Eddison’s own letters, to give us a more intimate portrait of the artist as a thinker and advocate for the power of his own writing. In particular, Young focuses on Eddison’s efforts to explain to friends, colleagues, and publishers the relevance of his Zimiamvia novels and the philosophical vision they proferred, which he saw as a corrective to the means-to-an-end mindset of WWII Britain that could reorient readers of the greater stakes of the war: to eliminate the evil of petty men, yes, but more importantly to attain a life whereby service to Aphrodite—to Beauty, Perfection, Reality—can be practiced.

Young’s reading not only of the Zimiamvia novels but of Eddison’s personal correspondence is incredibly compelling—and baffling. Compelling, because I think he’s right and it confirms my own reading and difficult struggle with Eddison’s work, and baffling because, truthfully, I don’t know what the fuck Eddison is talking about. As Young glosses it:

What Eddison was doing in the Zimiamvia cycle, therefore, was redefining the ultimate goals of morality and ontology, predicated on a quite warm-hearted assumption of the central importance of the individual pursuance of interpersonal affection, as precipitated, to his mind, by women. Consequently, our central responsibility as people is to Aphrodite, the classical goddess of love, who is invoked and incarnated on numerous occasions in the Zimiamvian novels. (75)

I have to object that anything about Eddison’s rejiggering of morality and ontology is “warm-hearted,” even if it is anchored in some (to me, absurd) notion of manly, heroic devotion to a worthwhile woman as the highest good—an idea that leaves the question of women’s role in Eddison’s whole cosmology, except as passive recipients of devotion, completely unanswered. And, truthfully, I have no idea what the fuck a life lived in devotion to Her looks like. It’s giving banal “Live Laugh Love” vibes, but in the accent of an Edwardian gentleman obsessed with pre-modern warfare.

The conditions of modern war and, more importantly, the lost potential for men to prove their heroic mettle as they could in Eddison’s romantic vision of days past, is a guiding light of Eddison’s work and is, in essence, a powerful form of critical anti-modernism. Adam Roberts observes in Fantasy: A Short History that “fantasy is not about the past”—or, I might interject, not solely about the past, in much the same way that science fiction is not solely about the future, though its orientation points to those temporal realms—“but about the present from which it flees” (xv). Roberts reads fantasy’s preoccupation with history, specifically with pre-modern pasts, as “fleeing” from the present. It’s an overgeneralization that implies a negative relationship between fantasy and the present, that suggests escape or escapism as a fearful, even life-preserving function of the genre (or mode or form). This is interesting, not least for what it says about Roberts’s own view of the genre, but I would prefer a more neutral framing.

Put another way, the anti-modernist impulses of Eddison or Tolkien or Peake or any fantasy can only be understood as anti-modern insofar as such impulses or energies or undercurrents or overtones—or whatever other terms we might use to characterize the textual, generic, formal, or modal effects of fantasy: that is, what fantasy does—are understood as responding to, as critiquing, as offering an account of modernity, of the present. Of course, fantasy doesn’t have to be anti-modern, and there are certainly ways in which all of these authors I’ve made examples of here are distinctly modern (for one, in their choice to write fantasy, a decidedly modern form). But anti-modernism is a mode of critique for a writer like Eddison, who sees his fantasy not (just) as an escape (indeed, Zimiamvia, the place of ostensible escape, is Real for Eddison in a way that our world is not), but as a philosophical tool for thinking about the problems of the present—and, importantly, offering a solution. To reformulate Roberts’s claim above: fantasy operationalizes the past to defamiliarize the present.

For Eddison, the nature of modern, mechanized warfare on display in both WWI and more so in WWII, is anathema to his vision of heroes doing great deeds. And so Eddison defamiliarizes modernity by relegating it to the status of a secondary world, rendering it as the sub-creation of the Real, fantasy world—a space where heroism is the natural state of a few good men tasked with great deeds. By contrast, survival in the wars of the twentieth century is understood as merely utilitarian (it had to be done); such war admits no moral value, unlike the victory of a hero, fighting against great odds, on Zimiamvia. Young suggests that Eddison’s novels showed how true service to Aphrodite could be wrested back from modernity in the “laboratory conditions” of fantasy:

Eddison therefore attempts to get his characters competing not on the grounds of mechanical power, wealth, or even martial prowess, but through their humanity alone. They could not do so on Earth, he appreciated, where utilitarian laws, technological distractions, and moral uncertainties provided unavoidable hobbles to human potential. In Zimiamvia, as on Mercury, those problems could be removed, and Lessingham could be the true hero he really is. He defeats his foes through skill, daring, and bravery, not by having more or better tools, and is applauded for doing so because his actions in the service of Aphrodite are, ipso facto, the right thing to do. This is not escapism or idealism so much as humanism espoused to a level of purity that could only be maintained under the literary equivalent of laboratory conditions: the secondary world. (79)

Again, I object to the idea that this is a kind of pure humanism (in fact, I see no humanism here, just gross individualism), as much as I reject the idea that there is anything worth praising in the figures of Lessingham or, in The Mezentian Gate, Mezentius or Barganax. Certainly, there is nothing admirable about Fiorinda or any of the other self-conscious avatars of Aphrodite. And that is the trap of Eddison’s fiction: it doesn’t matter what I or anyone else thinks of these characters. They are, in Eddison’s fictions, True. And because True, they are Beautiful and Real.

As Young notes, Eddison’s novels do away with “ethical good,” relating goodness only to the human world, to the lower plane of existence—which, again, in this novel as in A Fish Dinner in Memison is created, briefly, for a mere thirty minutes at a dinner party so that Mezentius and Fiorinda can observe what a horrible, mechanical world ruled by cause and effect would be like, and experience it by living temporarily mortal lives as Lessingham and Mary—where doing good or bad deeds is merely what humans have to do in order to survive. Ethical goodness was, for Eddison, “relative, subject to convention & expediency” (qtd. in Young 80–81), and therefore not True because Truth and the Real are not relative, but objective and eternal and enduring (sub specie aeternitatis, as Doctor Vandermast is fond of reciting). Evil, insofar as it exists, was for Eddison found only in men who cannot accept that they are beaten, and so scheme temporarily against the eternal hierarchy of things. This explains Hitler or even the Soviet Union, in Eddison’s mind. His Zimiamvian novels, then, were important to the mechanical conflict of WWII, and its temporary efforts at producing a utilitarian, ethical good by defeating fascism, because they could put the whole conflict into greater perspective. Young nicely frames the value of fantasy as a mode for Eddison,

The fact that he saw [his] work as applicable to the situation [of WWII] at all is crucial. It exemplifies his desire to make sense of reality by taking a step back from it and his keen appreciation of the value of fantasy literature as a method of mounting such critiques. This, in turn, demonstrates a clear understanding of the partnership between fantasy and reality, and the fact that no resonant fantasy can afford to ignore the problems of reality. (82).

Young is quick to point out that for all his ideas about WWII as a merely utilitarian necessity of the present, Eddison nonetheless cared greatly about the outcome of WWII. He also despised Hitler and felt that Hitler manifested evil not by virtue, say, of anything to do with his politics, but because Hitler “was unable to accept his defeat in World War I and […] had taken advantage of circumstances to gain a position where he could use technology to vent his frustrations upon millions” (84). It’s notable that Eddison understands his fiction as fantastically recovering a space of possibility for humanity to act in service of what really matters—Aphrodite, Beauty, Truth, Reality—by undertaking heroic deeds that serve Her. Eddison’s ideas in this regard ran toward the fascistic, suggesting that our sad modern reality could not produce true heroes, the “aristocracy” of good men who could overthrow the “kakistocracy” that ruled us. His own friends, including Gerald Hayes, who drew the maps of Zimiamvia published in every volume, complained that Eddison’s heroes and the ideals they espoused were “sheer, bloody Fascism” (qtd. in Young 83).

Young argues that accusations that Eddison’s work is shot through with fascist tendencies—claims forwarded by a number of critics—misapprehend Eddison’s ideas about aristocracy, since Eddison apparently believed that the true aristocracy of heroes did not exist in our world, at least not anymore. It was an ideal only possible, say, in the pre-modern era or in Zimiamvia, but one we should nonetheless work toward attaining through devotion to Her, however petty and small such devotion might be in our modern, mortal, unheroic state. I think Young is ultimately doing way too much to defend Eddison. His essay is a magnificent exploration of Eddison’s own ideas and for that it is incredibly valuable, but Young fails to go the step further, to critique Eddison’s ideas and to question why, then, so many critics are rightly concerned about his philosophy. Not only is Eddison’s idea of devotion to Her, frankly, nonsensical, but his belief in an aristocracy of heroes coupled with his vision of the ultimate pointlessness of ethical good—for we live in an amoral universe where the only true good is service to Her—does, indeed, lead down fascist roads.

Young argues that Zimiamvia is explicitly about and for the world of WWII. But what concerns me is the idea of arguing against “ethical good” and against the relevance, at all, of ethics except as mere utilitarian distractions, something to “get by” in life as needed, in a time of both war against fascism but also at a time when the supremacy of the British empire was crumbling. Eddison’s ethos of rule by aristocracy is not only elitist, to say the very least and most obvious thing one could say about it, regardless of whether Eddison meant the aristocrats of his day or some lost, impossible heroic cabal of “good” men. More importantly, the idea is imperialist and—though he may have protested—fascist. It matters not whether any truly aristocratic heroes existed in our world, according to what Young describes as Eddison’s very specific, supposedly misunderstood definition of aristocracy. Rule of the many by a select, “good” few, as a naturalized representation of Beauty and Perfection? A fantasy that understands all of our sorrows and pains and injustices as minor because they are part of an imperfect universe, the playstage of the gods, and not Reality itself? A storyworld where Barganax and Fiorinda, Mezentius and Amalie are the paragons of divinity, where such figures transcend the value of the human? I struggle to see how anyone could find justice in such a philosophy. Then again, for Eddison, justice is beside the point; it’s not Beauty, after all.

To be sure, what Eddison really seems to be offering is a jumble of warmed over Nietzschean ideas: master-slave morality, the Übermensch, will to power, objective Beauty, and so on (although filtered through and combined with ideas from other philosophers, namely Spinoza). Eddison might be putting his own interpretation on these ideas, and he doesn’t seem beholden to the nihilism of Nietzsche, but Eddison seems ultimately to be driven by many of the same conclusions that energized Nietzsche. Bertrand Russell criticized Nietzsche’s ideas as the “mere power-phantasies of an invalid,” stating, “I dislike Nietzsche because he likes the contemplation of pain, because he erects conceit into duty, because the men whom he most admires are conquerors, whose glory is cleverness in causing men to die.” (History of Western Philosophy, 739).

Men “whose glory is cleverness in causing men to die” is an apt description of Eddison’s amoral heroic troupe of ideal aristocrats whose great deeds serve Her. Eddison’s vision of Zimiamvia, then, and of his fiction’s usefulness to the world, especially a world at war with fascism and a world on the brink of decolonial struggles, is one I have no sympathy for and which I reject. But Eddison’s articulation of fantasy as an anti-modernist tool and as an artistic mode for critiquing our world is nonetheless fascinating and interesting. Though I disagree, ultimately, with Young’s refusal to call Eddison’s spade a spade, the important historical and cultural contexts he offers us from Eddison’s own archive help us better understand Eddison’s fantasy novels as not just or not merely escapism, but to understand escapism as itself a political project—however we interpret the text’s politics.

Parting Thoughts

The Mezentian Gate is a strange draught—at once beautiful, dull, enticing, regressive, dramatic, and philosophical. Like the Zimiamvia trilogy as a whole, it’s a difficult text in more ways than one: to read, to parse, to like. But as I hope to have shown, understanding Eddison’s project, however much I contest its politics, has its own rewards since Eddison’s Zimiamvia trilogy gives us a clear, complex, and, yes, deeply problematic vision enabled by the affordances of fantasy.

While the Zimiamvia trilogy did not go on to be reprinted in BAF proper, its presence among the preface novels evidences its importance to the history of fantasy in this crucial moment of genrefication. While few then or today read Eddison’s novels, they are a testament to the power of fantasy as a genre, form, and mode. Eddison saw fantasy as a way of expressing politics and philosophy through worldbuilding and narrative, and vice versa, in a literary manner and with stunning clarity of vision that few authors since have managed to emulate. For Eddison, fantasy was escape as politics, as philosophy, in as much as it was a critique of the modern world and an attempt to answer its problems.

It’s unlikely that I’ll return to Zimiamvia anytime soon, if at all. But now that I’ve finished the trilogy, I am glad to have read it. The pleasures were few, but the rewards illuminating. And that’s all I can ask for, really. That’s the whole point of this Ballantine Adult Fantasy reading series: to read widely, to ask questions, to place things into historical and cultural contexts, and to learn how so many authors across more than a century used what we would come to call “fantasy” to make meaning, to create new worlds, and to envision new possibilities—and how, from the cacophony of their efforts (and some help from Ballantine, among others), a genre emerged.

And on that note, we finally head into the BAF itself, beginning with the series’s first novel: Fletcher Pratt’s The Blue Star.

To get notifications about new essays like this one sent directly to your inbox, consider subscribing to Genre Fantasies for free:

7 thoughts on “Ballantine Adult Fantasy: Reading “The Mezentian Gate” by E.R. Eddison (Zimiamvia 3)”