How Are the Mighty Fallen by Thomas Burnett Swann. DAW Books, 1974.

Table of Contents

Tell Me About a Complicated Man

Swann, DAW, and the Controversy

Reading How Are the Mighty Fallen

An Important Contextual Note

Parting Thoughts

Tell Me About a Complicated Man

King David of the Hebrew Tanakh is surely one of the great figures of ancient mythology. The story of the semi-mythic king told in 1 and 2 Samuel is that of a heroic figure just as complicated, passionate, unlikable, and as messily, compellingly human, despite his mythic proportions, as Odysseus or Achilles, Beowulf or Gilgamesh, Medea or Helen. Betrayal, lust, prophecy, murder, chosenness, power, exile, conquest, pettiness—all these swirl together in the epic of David. He is best known for slaying Goliath with a sling when he was still a youth, an event which has served as a powerful mytheme for both Jews and Christians, and for secular, religious, and (ethno)nationalist purposes alike, for nearly three millennia. But he is also known for the lust, adultery, and murder that caused God’s wrath and led to the death of his first child with Bathsheba (in religious circles, such a story exemplifies that great men sin but their sins are forgiven; it proffers a powerful shield for those who abuse their authority). Emily Wilson’s 2017 translation of The Odyssey renders the epic’s immortal first line, compellingly but not uncontroversially, as: “Tell me about a complicated man” (105). She, or Homer, might as well have been speaking about David.

Translator and comparative literature scholar Robert Alter argued that David’s story was one of the most significant in all of Western literature. He embarked on his impressive literary translation of the entire Tanakh with the publication in 1999 of The David Story, rendering 1 and 2 Samuel in beautiful, lyrical English along with copious critical commentary. The book’s cover copy loftily asserts:

The story of David is the greatest single narrative representation in antiquity of a human life evolving by slow stages through time, shaped by the pressures of political life, family, the impulses of body and spirit, and the eventual sad decay of the flesh. In its main character, it provides the first full-length portrait of a Machiavellian prince in Western literature.

The marketing copy is annoyingly hyperbolic, for sure, and the claims to firstness are—as all such claims—highly debatable. But this necessary pedantry aside, it’s clear that scholars, believers, artists, and critics have enjoyed David’s story for millennia and continue to do so into the present. This year, for example, saw the release of both a big-budget historical drama TV show, House of David (co-produced by Amazon Prime Video and Christian studio The Wonder Project as a kind of evangelical’s House of the Dragon), and two interrelated children’s animated projects: the TV miniseries, Young David, and the sequel feature-length film, David.

More than fifty years ago, Thomas Burnett Swann found David’s story compelling, too, and made David the topic of his eighth and most (in)famous novel, How Are the Mighty Fallen (1974). The previous decade had seen at least three major film adaptations of David’s story, including one with Orson Welles as Saul, and Swann was highly influenced by Gladys Schmitt’s bestselling 1946 historical melodrama David the King, which he called, in his own novel’s acknowledgments, “the finest Biblical novel ever written” (160). But because this is Swann, an author who always brings to his novels his own strangenesses, his own unique interpretation of both the ancient world and the mythological texts he partially adapts, How Are the Mighty Fallen is no simple retelling of the story of David smiting Goliath, of the mad King Saul of Israel and his warrior son Jonathan, of Queen Ahinoam and the concubine Rizpah. It is all of that, yes, and more: a bold tapestry of Greco-Roman, Hebraic, Phoenician, and Philistine myths with a deep knowledge of the history and archaeology of the eastern Mediterranean during the early Iron Age (perhaps c. 1000 BCE; possible dates of David’s reign are all over the place) interwoven with Swann’s cycle of historical fantasies—told over most of his 16 novels—about the “prehumans,” mythic beings like Centaurs, Dryads, and Fauns who lived egalitarian lives of pleasure in harmony with nature before the violent rise of human civilization drove them into obscurity and death, or else transformed them into monsters hunted and hated by humanity.

This particular tale tells mainly of two prehuman peoples Swann had yet to introduce to his historical fantasy milieu: the Sirens and the Cyclopes. But How Are the Mighty Fallen is also not Swann’s first retelling of an ancient Hebrew story. Swann’s third novel, Moondust (1968), loosely adapted Joshua and the Israelites’ invasion of Canaan and, specifically, the Fall of Jericho—and it also departed from Swann’s prehuman stories set in Crete and Italia, most of which feature Dryads, Centaurs, Fauns, even Minotaurs, and occasional recurring beings like Water Sprites, Thriae, Telesphori, and the Bears of Artemis. Moondust, however, was surprisingly weird and told about the history of ancient mothpeople and the evil telepathic fennecs who enslaved them, offering a truly strange and utterly different vision of the prehumans far outside Swann’s more familiar territory of Greco-Roman myth (though Swann never failed to take massive, inventive liberties in the telling).

How Are the Mighty Fallen is very much in the tradition of Moondust, in that it tells about beings we’ve yet to see in Swann’s prehuman stories, and does so within the context of the Hebraic stories of the Tanakh, but the novel also tries to connect the ancient Israelite world of Moondust to Greco-Roman myths and the wider contexts of the ancient Mediterranean world. What, after all, do Cyclopes and Sirens—those figures best known from The Odyssey—have to do with the ancient Israelites? And why is How Are the Mighty Fallen Swann’s most (in)famous, even controversial, novel?

Swann, DAW, and the Controversy

How Are the Mighty Fallen was Swann’s second of six books published with DAW Books, owing to Swann’s close editorial relationship with founder Donald Wollheim, who had first published Swann at Ace Books, beginning with Day of the Minotaur (1966), and so essentially started Swann’s career as an sff novelist. Publishing How Are the Mighty Fallen with DAW was a smart choice, too, for the novel proved controversial enough that DAW’s distributor, New American Library, intended to ban the novel. But Wollheim was a fierce defender of his writers’ self-expression, even if/when it might have offended him (e.g. John Norman’s Gor series), and he ultimately won the fight with NAL and Swann’s book shipped.

If you’re unfamiliar with How Are the Mighty Fallen and still wondering why the book was controversial, perhaps the cover copy will help:

Cyclops and sirens, halfmen and godlings…

That of which myths are made and that from which worship arises—these are the materials Thomas Burnett Swann weaves together in the fantasy-historical tapestry of this new novel, which he considers to be his most important work to date.

For the author of Green Phoenix and The Forest of Forever now tells of a queen of ancient Judea who was more than human, of her son who became legend, of their Cyclopean nemesis whose name became synonymous with Colossus, and of loves and loyalties and combats fixed forever in the foundations of human society.

The ever-growing audience that Thomas Burnett Swann has gathered for his unique novels will find How Are the Mighty Fallen a new fantasy fiction experience.

Or maybe it won’t? Surely the interior copy, which gives us a glimpse of a scene from the novel, will clear things up:

I was a queen, Jonathan, in my own land, and my lovers were as numerous as cells in a honeycomb. My people, the Sirens, had come to Crete in the Golden Age; come from their northern home to live in that southern land with the Wanderwooders, the Satyrs and the Dryads, the Leogryphs and the Telesphori. Wings to fly, legs to walk, webbed toes to swim: the ideal race, were we not?

The ruined palaces of the Cretans, sprawling over the land and into the sea, gave us a home, a hive where a queen could rule her drones and workers and propagate the race. But we made of those half-sunken palaces a place of warmth and delight.

I was only a child when the first Cyclopes came to the island. I had become a queen when they threatened you, my son of five years… (emphasis in original)

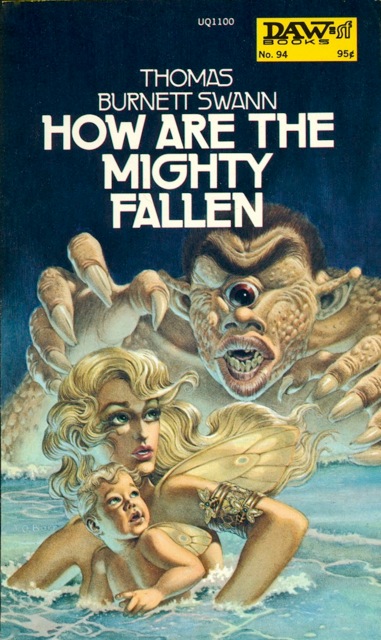

Sirens and Cyclopes, honeycombs and hives, the paradise of Golden Age Crete—only Jonathan’s name gives us a hint that this is a novel adapting a tanakhic tale, and not one of Swann’s more usual stories of Crete or Italia. But it’s a vague hint, and the cover and interior copy, together with George Barr’s cover painting featuring a leering Cyclops, seem to suggest that this is a story about the conflict between the Sirens and the Cyclopes, much as, say, The Forest of Forever (1971) was about the conflict on Crete between the invading Thriae and the other prehumans.

But How Are the Mighty Fallen is only partly about Sirens and Cyclopes. Their conflict is certainly an important, motivating factor in the narrative, but it pales in comparison to the main focus of the novel, which is unspoken in the book’s paratexts, but which was responsible for the novel’s near-banning from distribution: the novel is about queer love between Jonathan and David. Like most of Swann’s novels, romance between two (or three) characters is the central driving force of the narrative, everything else swirling around the romance as either context for or a challenge to that love; and, like many Swann novels, there is a strong element of tragedy. Jonathan, after all, is killed in 1 Samuel along with his father, Saul, and his brothers at the Battle of Mount Gilboa, where the Philistines crush the Israelites—a moment that inspired David to write a lament for Saul and Jonathan (2 Samuel 1:19–27), including the refrain: Eykh, naph’lu giborim (my transliteration), often rendered “How are the mighty fallen!”

I have a suspicion that a compromise might have been reached with New American Library to allow distribution of How Are the Mighty Fallen, but only if the book didn’t sell itself as an adaptation of the David story, instead emphasizing the novel as one of Swann’s typical tales of the prehumans. Only the name Jonathan and the reference to “a queen of ancient Judea” appear in the copy, and these are vague enough as to be glossed over by all but the carefulest readers. Not to mention Barr’s cover art, which adapts the idea (but not facts) of a minor scene in the novel and suggests a Greco-Roman story about Cyclopes and whatever these Sirens are—for in this art, and indeed in Swann’s own rather confusing description (more later), they appear as something like Britain’s fairies. Swann felt the cover gave the wrong impression of the kind of novel he’d written (and, to be fair, he was plagued by covers that misunderstood and misrepresented his work; Swann was only ever pleased by the cover of Moondust by Jeffrey Catherine Jones, an artist who later came out as a transwoman). Barr also provided some rather juvenile interior illustrations that mostly underscore critics’ (unearned) complaints that Swann’s fiction Disneyfied their noble topics.

Wollheim’s support for Swann’s work and his defense of it for the controversy of being an openly queer love story, let alone one about an important figure from the Tankah/Bible (remember: Jesus is understood as a descendant of King David), is not all that surprising. Wollheim was a member of the early trans community, Casa Susanna, and wrote a biography of his experiences, A Year Among the Girls (1966), under the pseudonym Darrell G. Raynor. He identified in the 1950s–1970s as a transvestite and his daughter Betsy Wollheim (president, co-publisher, and co-editor-in-chief of DAW since 1985) describes his experiences in a recent interview. Notably, Betsy discovered her father’s identity when Donald was preparing for a party at Lin Carter’s house—and Carter’s first volume of The Year’s Best Fantasy (DAW, 1975), which he began after Ballantine shuttered the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series, named How Are the Mighty Fallen as one of the ten best fantasy novels of the year.

Betsy described her father’s affinity for writers like Swann in a 2025 interview for Black Gate:

Interviewer: He published a lot of Thomas Burnett Swann.

Betsy: He did. He published a lot of gay authors. […] There is a reason my father was partial to gay and alternative sexuality and gender culture. He was part of the very first ever trans woman’s group in America. […] It was a very early group of mostly white, intellectual, well-educated, cultured men, most of whom were transgendered, but they all liked to dress in women’s clothing. They called themselves transvestites, because it was very early in the 1950s and 1960s and that’s the name they chose for themselves. Yeah, he was very partial to those people and many of our friends were transgendered, lesbian, gay people when I was a kid.

I should note that this is the only instance I’ve found where a person who might have actually been acquainted with Swann refers to him openly as gay. I don’t know if Betsy knew Swann personally, if she had this information about Swann from her dad, or if this was a general (if possibly unconfirmed) belief about Swann in the sff community. To the latter point, Swann’s friends used several possible euphemisms for gay or queer to describe him, especially “gentle,” a term with which Swann characterized many of his obviously queer characters, including Jonathan in How Are the Mighty Fallen.

Reading How Are the Mighty Fallen

How Are the Mighty Fallen opens with the Israelites’s triumph over the Philistines at the Battle of Michmash, a victory masterminded by King Saul’s son Jonathan and his armorbearer Nathan. Queen Ahinoam has come to the soldiers’ encampment to succor her son, “a princely paradox,” a young hero aggrieved by the killing he must accomplish to safeguard Saul’s kingdom, who is “happiest in Gibeah, where he planted trees and trees read scrolls and played the lyre and enjoyed his brothers and sisters almost as if they were his own children” (18). Swann’s Jonathan is made in the mold of his Aeneas in Green Phoenix (1972), a preternaturally young leader of men, too gentle and loving for this world, but nonetheless excellent in the art of war—and burdened with melancholy for that skill. Jonathan rejects the heroism that falls easily on his shoulders, weeps for his enemies, and sees all men as equal. And like Ahinoam, Jonathan is unnaturally, divinely beautiful; both compel great loyalty from the Israelites for their kindness, sincerity, goodness, and, of course, for their unsurpassed attractiveness. And, at the same time, both are a little suspect: Ahinoam for her foreign origins in Caphtor (i.e. Crete), believed to be the original home to the Philistines, and Jonathan for his secretiveness, the fact that he bathes so often, that he does not disrobe in front of the other soldiers, that he doesn’t sleep with the many women who would gladly take him as a lover (despite Yahweh’s strict decrees). As David’s brothers put it, “He is much too gentle for any man. No one can be so good. No one can be so chaste” (36).

Ahinoam’s arrival at the Israelite camp, however, is greeted not with the excitement of soldiers celebrating a great victory, but with quiet and frustration. The prophet Samuel has decreed that, despite their victory, no Israelite may eat or drink until the sun has gone down. Saul, his brother Abner, Saul’s concubine Rizpah, and most of all the Israelite soldiers—all are frustrated by Yahweh’s insistence on fasting and sacrifice in the wake of a successful military campaign. Thus Swann introduces a major theme of How Are the Mighty Fallen: that the Israelites’ Yahweh, in Ahinoam’s rebuke to Saul, “has not given you laws, he has shackled you with them,” denying to humans what gives them pleasure, and what is therefore “good” (13). Ahinoam denounces Yahweh as merely a local mountain god, a divinity who is petty and jealous because of his localness. Yahweh is contrasted to “the Goddess,” whom Swann calls Ashtoreth in this novel, a name cognate with Astarte and Ishtar, which collectively designate an ancient Near Eastern goddess of love, war, and hunting shared by Canaanites, Philistine, Phoenicians, Assyrians, Babylonians, and even the earlier Sumerians, who called her Inanna. Importantly, one of the threads Swann weaves into his previous novel, Wolfwinter (1972)—his first novel to emphasize ethical good as service to “the Goddess”—is that Aphrodite, Artemis, even Athena are all different faces, aspects, or avatars of a singular Goddess, the progenitor deity of the prehumans, referred to in earlier novels by Swann as the Great Mother. The Goddess is a universal deity and therefore superior to—and more just than—Yahweh.

The early portions of How Are the Mighty Fallen emphasize Yahweh’s injustice and the negative effects his proclamations, channeled through Saul and the tinkling bells hung on a sacred terebinth tree, have on the Israelites. His followers, especially Saul, are rendered as tragic figures precisely because they follow Yahweh uncritically, even though the god’s dictates bring pain, frustration, and loss of identity that drives Saul into madness and self-hate. The first glimpse of this is the strictness of Yahweh’s edict that no Israelite may eat or drink in celebration of the Michmash victory. Jonathan, who was not present for the decree, ate a berry and for that Yahweh will punish the Israelites until a human sacrifice is offered. Referencing Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice Isaac at Yahweh’s command, Saul agrees without hesitation to kill Jonathan. But the Israelites are furious and Jonathan’s armorbearer Nathan gives himself in Jonathan’s place as a scapegoat, which appeases Yahweh.

The event highlights religious tensions and fears among the Israelites, namely that Yahweh is too strict a god, that the Canaanites or Philistines have more accommodating deities, and that, other than the cultural and familial heritage of being an Israelite, there seems little reason to adhere to this vindictive god. A telling exchange underscores this:

Jonathan thrust himself between Nathan and Saul. “You are not to have him,” he said to his father in a low but deadly voice. “He is my friend.”

“Would you question the ways of Yahweh?”

“Yes, my father, I question his ways. Or rather, the manner in which you interpret them. I would worship a pitying Brother or Mother instead of a heartless Father who hurls thunderbolts to vent his displeasure and kills young boys for the mistakes of their masters.”

“You’re speaking like a Canaanite,” said Saul with dignity but without reproof. (24)

Jonathan’s claim that he would rather worship a brother or mother before a violent father identifies Saul with Yahweh, and foreshadows both Saul’s vicious turn against Jonathan and the future king David, as well as Jonathan’s praise of David (“brother”) and Ahinoam (mother) as figures who represent the good of the Goddess in contrast to Yahweh. Moreover, Saul’s quip about the Canaanites is not merely a reference to conflict between the Israelites and this historic enemy, but a comment on the homoeroticism of Jonathan’s relationship with Nathan. For Nathan’s self-sacrifice is not just born from the loyalty of an armorbearer for his prince, or of a comrade-in-arms for another warrior; it is these things, but also a (unfulfilled) romantic love. When Nathan is executed, his only and final word is “Jonathan” and Ahinoam sees on Jonathan’s face “anguish for the loss of a beloved” (25).

Within the first twenty-five pages, Swann establishes How Are the Mighty Fallen as a critique of homophobia—not just as individual acts of hate or violence, but as a cultural and theological system of oppression that is explicitly violent and unjust—filtered through a familiar narrative from the Tanakh and placed in the milieu of Swann’s “secret history” of the prehumans in the ancient Mediterranean world. As if this weren’t clear by the time of Nathan’s execution, Swann’s characters make regular references to “the sin of Sodom” and the widespread practice of love between men among the Philistines as equal to that of love between men and women (lesbian love is not discussed and Swann explicitly uses “men” and “women,” not “boy” or “girl”). The narrative, essentially, tells of a cultural struggle by those raised up in the strict, heteropatriarchal Yahwism of the Israelites, seeking the freedom to love as they will, and describes, also, the cultural conflict between what Swann imagines as a more sexually egalitarian polytheism and the hierarchical, homophobic gender relations of a petty god who imagines himself as the only god.

When Swann describes David meeting Jonathan for the first time, it is cast in explicitly romantic tones, almost as a holy revelation. David—a shepherd of 16, Saul’s armorbearer, and a bard of astonishing skill whose psalms soothe Saul’s bouts of madness—meets “a young man with a dusty tunic and the face of a god,” that is, Jonathan, about age 20, and observes firstly and most fondly his eyes and lips (Swann devotes three lines of description to each!). To David, Jonathan is “too beautiful” and “has about him the transience of perfection,” “a fragility” that “can only be broken” (33). But this experience challenges David’s understanding of himself and his conception of masculinity, for it is the Philistines and not Israelites who “speak of masculine beauty” (33). The brief meeting has a transformative affect on David, for when he returns to Saul’s tent, “he felt the terrors of a bridegroom going to meet his betrothed’s father for the first time” (34), and he performs a song for Saul, Psalm 23, “The Lord Is My Shepherd”—only the “Lord” to David’s metaphorical lamb is Jonathan (their relationship ultimately reverses this dynamic, casting David as the protector).

Later, David joins Jonathan in his “tent of mysteries” and Jonathan hesitantly expresses his queer desire for David, stating that he is “Afraid for you to read my soul and perhaps turn away from me” (39). David hardly understands, especially when Jonathan expresses that he has no desire to rule, that princeship is a burden to one such as him:

“Some men are meant to rule kingdoms[,” Jonathan said. “]Others—”

“To what?” [David asked.]

“To love.”

“And you’ve loved, haven’t you, Jonathan?”

“Not as I would choose.”

“Why, half the women of Israel—wives included—would lie with you.”

Jonathan’s eyes did not waver. “I do not want to lie with the women of Israel or any other land. (39–40)

Swann, here, seems to be forwarding an idea about the right to choose who one loves as a fundamental aspect of self-fulfillment, a notion he developed previously in Wolfwinter, and he makes this idea of one’s choice (of whom) to love as a kind of fulfillment clearer with imagery of the moon, when Jonathan remarks,

My mother says that the highest love is a circle, not a crescent. The crescent moon—friendship or love for family—is pure and silvery. But the full moon is orange and abundant and includes all the lesser loves in its circumference. (40)

Jonathan seeks the full moon of romantic, life-partner love with David, but the future king rebuffs him initially, not out of fear for the supposed sin of their queerness, for David cares little about Yahweh and his dictates, but because Jonathan reveals his nonhuman heritage by casting a glamor spell that makes him look, briefly, like an enticingly feminine Nereid—a cruel joke that Jonathan means to dissociate David’s ideas of beauty, gender, and desire.

After David leaves Jonathan’s tent, Ahinoam, who has recognized Jonathan’s earlier, more-than-friendly affection for Nathan and his newfound love for David, comes to Jonathan and gives him the “I know you’re gay and that’s OK” talk. In a lengthy scene, she recounts that Jonathan is not an Israelite, not the son of Saul, but he is like her: a Siren. She then describes how the Sirens displeased the Goddess by preying on sailors, and so were exiled from a land of forests, of fir and pine, and at the same time the Goddess took away their ability to fly, stunting their wings into vestigial little things. So the Sirens swam to Crete, arriving after some cataclysm that caused the original human inhabitants—the ancestors of the Philistines—to flee the island. The Sirens took up residence in the humans’ abandoned, half-drowned palaces, and made friends with the other Beasts of Crete described in Day of the Minotaur and The Forest of Forever. They built their honeycomb hives and lived near-paradisiacal lives in their bee-like society of all-male drones and workers ruled over by exquisite queens like Ahinoam. Eventually, the violent, lustful Cyclopes came and made enemies of the Sirens, who refused to give up their bodies to the brutes. One Cyclops in particular assaulted Ahinoam and destroyed her hive, and Ahinoam fled into the sea with Jonathan, her five-year-old son, born from a nuptial flight with the love of her life, a drone she disemboweled as all drones are disemboweled in the horny frenzy of Siren mating.

The revelation that his mother is a Siren, not just a supernaturally beautiful and powerful foreigner, and that he, too, is a Siren, is unsurprising to Jonathan. After all, he has tiny, stunted, apine fairy wings—perhaps a bit on the nose, with the fairy metaphor. Moreover, Ahinoam tells Jonathan this story not only to reveal his true identity, but to naturalize and normalize his queer desire, his feeling that he is not meant to love women, but men. A key part of Ahinoam’s story of Crete is that two of her favored drones were madly in love, and their love was beautiful and righteous. These drones, Myiskos and Hylas, Ahinoam recalls, “In perilous times […] could speak of flowers. Yet, under attack from the Cyclopes, they were valorous warriors; the two of them fought as one” (47). Using Myiskos and Hylas as examples, Ahinoam delivers her lesson:

The Goddess never decreed that men should lie only with women. All of the races which worship her—the Wanderwoods [i.e. the prehumans, using a term from Green Phoenix], the Cretans, the Philistines, the Canaanites, the Phoenicians—accept the love between two men as one more affirmation of the divine plan, the tide which rises and falls to the moon’s compulsion, the inevitability of the seasons, the certainty that those who love will meet, after death, in the Celestial Vineyard. A man’s love for a man is neither more nor less than a man’s love for a woman, it is only different. (46–47)

Ahinoam’s—and by extent Swann’s—defense of queer desire and love, not just as natural, but as cosmologically sanctioned, as “one more affirmation of the divine plan,” a kind of love that will be reflected and celebrated in the Sirens’ version of heaven (a paradise in the sky, as compared to Yahweh’s dreary underground ghost-realm of Sheol), is a simply astonishing argument for the right to and rightness of gay love, a remarkable statement for any text published in 1974 and made all the more astounding for being published in a tanakhic/biblical historical fantasy novel.

This background to the Sirens also does some interesting reworking of Swann’s prehuman mythology, much as Wolfwinter did for his earlier vision of the Fauns. What the Sirens are, exactly, is unclear. They are certainly polysemous and somewhat confusingly so. They map to the ancient Greek idea of sirens as water-dwelling dangers to sailors (the ones whose call Odysseus listened to while tied to his ship’s mast), but they are not mermaids (Nereids or Tritons, in Swann’s prehuman taxonomy), and they are also reminiscent of British fairies, of the nineteenth-century German Lorelei legend, and most immediately of Swann’s Thriae. The Thriae were bee-people and partial antagonists in Swann’s Cretan tales, Day of the Minotaur and The Forest of Forever. They were a devious, violent race of prehumans banished from Asia, and who blew into Crete from the north during a storm. They, too, were a society of workers and drones ruled over by a singular queen who built a honeycomb hive and disemboweled her mate in an annual nuptial flight (and both Ahinoam and Jonathan share the Thriae’s problematically “slanted” eyes). The Sirens of How Are the Mighty Fallen, then, almost read like a revision of Swann’s earlier Thriae, ascribing them to a preexisting mythological archetype—the Greek siren—but blending them with new elements to make them, as most things, uniquely his own (for what it’s worth, he also revises the Bears of Artemis in this novel, giving them the new name Artori, making them all-white instead of panda-like, and making them both male and female, where before they were only female).

Shortly after these revelations, Jonathan becomes sick with fever while the Israelites are embarked on yet another of their endless wars with the Philistines. And Goliath has come, raising a challenge to Saul that, if the Israelites will just send forth a champion, the war can be ended with single combat. This is the crux of the David story and Swann’s adaptation makes it unique in two ways. The first is that Goliath is a Cyclops as are his brothers from Gath, mercenaries hired by the Philistines—and Goliath is the Cyclops who assaulted Ahinoam, destroyed her hive, and killed her brave queer warrior-lovers, Myiskos and Hylas. The second is that David takes up arms against Goliath (a rather uninteresting scene in Swann’s telling) in order to defend and prove his love for Jonathan, and he slays Goliath with the aid of Ahinoam’s magic, which briefly confuses the Cyclops with his own hideous reflection before David lands a tourmaline stone, a gift from Jonathan, in the Cyclops’s eye. David, then, as we know, becomes a favorite of Saul, eventually marrying his daughter Michal, and gains the attention of the prophet Samuel, who anoints David as the future king of Israel, leading to his exile by Saul. Later, after Saul and his immediate heirs are (conveniently) killed in a battle with the Philistines while David is still in exile, David returns and unites the two kingdoms of Israel and Judah into a single Israelite state.

That’s the story as we know it, and Swann does not really deviate, but, as with Green Phoenix’s adaptation of Virgil’s Aeneid, he works his story into the interstices of the tanakhic text. For the slaying of Goliath leads, ultimately, to the consummation of his and Jonathan’s relationship, to their declaring of love for one another, initiated first by David. When they finally come together,

It did not seem to David that only then did they embrace as more than friends; it seemed to him that there had never been a time when they were less than lovers. Arm in arm they had crossed impassable deserts; side by side they had sailed impossible seas, farther than Sheba or Punt; beyond the edge of the world! Other lands had known them; in other times they had loved and shared the throne; the high-breasted Lady of Crete, twining snakes in her hands, had smiled beneficence on them; they were as young and as old as the pyramids. (90)

This love, David feels, transcends time and space, is everything and everywhere all at once. In their time together, David and Jonathan debate the sin of Sodom but reject the story as bullshit propaganda intended by prophets like Samuel to enforce the dictates of a mirthless god. David again takes the lead, assuring Jonathan that “A sin is when you hurt people,” and therefore, because they find only pleasure in one another—and a transcendent pleasure of destiny and self-fulfillment—there can be no sin here (94):

Jonathan smiled and opened his arms, and David remembered watching Ahinoam, alone in a forest glade, open her arms to Ashtoreth and pray that the lovely and the loveless should find love. He entered Jonathan’s embrace and seemed at last to know the fulness of the sea, which had tantalized him with fitful flickers, an image, a scent, some words in a song; for he entered a world where dolphins snorted in leaping multitudes and Sirens combed their tresses with combs of coral; and then they were under the sea, he and Jonathan, and the leaves of the oak tree [they are in a tree house] were fathoms of cushioning water, and they swam into a cave where clumsy, amiable crabs brought gifts of amber between their pincers and a friendly octopus arranged them a couch of seaweed and sea anemones.

Jonathan held him with a wild urgency, meeting mood for mood, making of touch a language more articulate than song, and in that ancient oak tree the eternal Ashtoreth was honored more richly than by prayer or sacrifice… (94, ellipsis in original)

As ever, Swann’s rendering of emotion, desire, and sexual love paradoxically leaves little unsaid without saying anything explicitly. The scene abounds in beautiful imagery and extended metaphors that, I think, far surpass and outshine mere erotica, and instead capture the timeless mood of the two lovers, the sublimity of the (homo)erotic as an aesthetic experience as much as a physical and emotional one.

Powerful and exquisite though the scene of David and Jonathan’s love is, it is also a fleeting two paragraphs and, from here on out, the novel develops their relationship very little. The rest of the novel mostly follows the arc of David’s relationship with Saul, his marriage to Michal, and his exile from Saul’s kingdom—whereon he flees to Philistia. This is all told from Jonathan’s or Ahinoam’s perspective and we later learn that these events were partly manipulated by Saul’s concubine, Rizpah, who sees Jonathan and David kiss lovingly in Jonathan’s garden in Gibeah, and uses the event to stoke Saul’s paranoia that the two are plotting, as lovers, to overthrow Saul.

Along the way, there are trepidations about what David’s marriage to Michal means for his and Jonathan’s relationship, and it causes serious strain between the two, for Jonathan feels that David has chosen Michal over him—David protests: “Michal is a waterhole in the desert, but you are the Promised Land!” (105)—and that he could never learn to live a heterosexual life married to a woman, could never produce the heir Saul wants. To ease his worries about women, David takes Jonathan to a courtesan, the Witch of Endor, who turns out to be Ahinoam’s Siren friend from Crete, Alecto. And, in a night of drug-induced passion (which the novel insists stoked a real, if temporary love between the two), Jonathan unknowingly impregnates Alecto with a Siren offspring, Mephibosheth (important to the Tanakh story, since David later uses this disabled child to legitimize his reign). Alecto is significant insofar as Swann uses the magic of the Sirens to explain how, in the Tankah narrative, the Witch of Endor could allow Saul, an Israelite and Yahwist, to speak with a dead person, Samuel, as though this were a Greek epic. Swann, then, uses his Greco-Roman prehumans to rationalize an otherwise rather strange and out-of-place event in the Tankah narrative, while also emphasizing that the Israelites exist in constant denial of the power of the Goddess, for it is Ashtoreth that gives Alecto the power to contact the dead.

When the novel ends with Jonathan’s death at the Battle of Mount Gilboa, David, Ahinoam, and Mephibosheth speak to Jonathan’s shade through Alecto’s magic, and they see his spirit and his physical body rise up on new, fully-grown Siren wings and ascend to the Celestial Vineyards. His ascension, like Erinna’s last-minute salvation on the doorstep of Hades in Wolfwinter, is a gift from the Goddess for his service to Her—for his deep and true love of David, a love that doubled as worship of the Goddess and which, as Ahinoam assured us, affirmed the divine plan. And perhaps, too, it was a payment for the tragedy of this love, for having sacrificed himself, in essence, as Nathan did, by loving queerly in a homophobic time and place. The novel ends, then, with David’s lament, given in an uncited translation:

I am distressed for thee, my brother Jonathan:

Very pleasant hast thou been unto me:

Thy love was wonderful, passing the love of women.

How are the mighty fallen,

And the weapons of war perished. (159)

Swann gives David’s own words from the Tanakh, as if to say, “see, it was there all along”—a fact of the historical past and the heritage of our culture—and so affirm the rightness and righteousness of his story about that wonderful love, passing the love of women.

An Important Contextual Note

In his acknowledgments, Swann offers a compellingly bare explanation for why he chose to write a novel about a queer relationship between David and Jonathan:

Scholars and general readers still dispute the question: Were David and Jonathan lovers as well as friends? The King James and most other English translations obscure the point. Guided by a curious but convincing book called Greek Love, I read a translation from the oldest Hebrew Bible, the Masoretic, which treats the relationship between the two young men in language as passionate as any to be found in the Song of Solomon. How Are the Mighty Fallen, then, is the story of a love between men. Shocking? Not when you know the men. David was a great poet and a great leader. Jonathan was a deeply gentle man in a harsh, ungentle age. In loving each other, so it seemed to me, they flouted the laws of Israel but obeyed a deity beyond their tribal god Yahweh […]. I have chosen to call her Ashtoreth, the Goddess, or the Lady. (160)

I love that Swann’s counter to the idea that queer love in the Tanakh/Bible might be shocking is “Not when you know the men,” and that his explanation of that, his reason for why the men would be understandably queer, is that one was “a great poet and a great leader” and the other was tragically gentle. It’s a wonderful train of logic that essentially says, “Why were they gay? Why not!” The suggestion is that greatness, poeticness, and gentleness are hallmarks of men who would, after all, worship the just Goddess above an unjust, jealous deity like Yahweh—and so why would they not be queer? Swann is also right in picking up on the eroticism inscribed in David’s lamentation for Jonathan, and present elsewhere in 1 and 2 Samuel. The translation he chooses to use when citing David’s lamentation and other psalms is uncredited, but arguments about the queerness of David and Jonathan’s relationship clearly circulated in the 1960s–1970s, as evidenced by Swann’s citation of the book Greek Love, even if Swann’s emphasis on the queer reading of the text somewhat anticipated developments in biblical scholarship (see Tom Horner’s Jonathan Loved David: Homosexuality in Biblical Times (1978)).

But what is Greek Love (1964), the book that touched off Swann’s interest in reimagining the relationship between David and Jonathan, and what is the term it describes? The book is a study of the history of pederasty, or, as the the author of the afterword, psychologist Albert Ellis (one of the founders of cognitive behavioral therapy), puts it in a blurb printed on the book’s cover: “the right of an older male to have a relationship with a young boy.” Pederasty was not an uncommon practice in the ancient world, and there were fraught debates in gay and lesbian communities during the 1960s–1970s over the role of pederasty and pedophilia in historical queer life, with many questioning whether it made sense to equate pederasty with homosexuality. The National Organization of Women rightfully drew a line in the sand for mainstream feminist and LGBT organizations, officially condemning pederasty as “an issue of exploitation or violence, not affection/sexual preference/orientation” in 1980, condemning organizations like NAMBLA. But Greek Love was written not by a gay activist trying to recover or contextualize a history of queer practices, but rather by J.Z. Eglinton—a pseudonym for Walter Breen.

Breen was one of the most well-documented and horrendous pedophiles in the history of the sff community. He was the husband of Marion Zimmer Bradley, with whom he groomed and sexually abused multiple children, including their daughter, Moira Greyland, for decades. Breen, like Bradley, was a major figure in sff fandom in the 1960s and 1970s, a regular con-goer and fanzine contributor. And by the 1964 publication of Greek Love, Breen’s pedophilia was already well-known in the sff world. His first conviction was in 1954 and he had several further accusations against him in the following years, especially in the early 1960s, which were widely discussed in fandom and dubbed “Breendoggle” in the fanzines, leading to Breen’s banning from several cons. Breen was even a founding member of NAMBLA, invited to speak at the first conference in 1978 because of Greek Love. He was later convicted for sexual abuse in the 1990s, at which point he and Bradley divorced and Bradley protested her ignorance (their daughter, Greyland, has testified to Bradley’s knowledge of and involvement in his crimes; notably, Bradley married Breen in the immediate wake of “Breendoggle,” not before). Breen’s Greek Love was intended to historicize and advocate for pederasty. According to some reviews I’ve read, Breen argues that such relationships should be the norm today, so that young boys can “learn” from older men whom they love and trust. And just to be absolutely crystal fucking clear: No. Fuck no! What the fuck? No!

Organized sff fandom in this period was a small, insular community and Swann was active in the fanzines, a prolific correspondent in letters with other fans, and attended two major cons prior to his worsening health in the early 1970s. It seems likely that Swann would have known of Walter Breen and probably that he would have been familiar with the (to my mind much too lightly named) “Breendoggle.” But whether Swann knew that Breen was the pseudonymous author of Greek Love is unclear. Certainly, it seems odd that he left off the author’s name in the acknowledgements, but (1) he didn’t always give the name of his reference works’ authors and (2) even if he had included it, it’s not clear if the fandom knew that Eglinton was a pseudonym for Breen. By making this connection explicit I don’t want to suggest a reading of Swann’s How Are the Mighty Fallen that associates the work, its content, or Swann’s own sexuality with Breen and his advocacy for pederasty. In fact, I’ve left this to the end so as not to prejudice the reading of what, I think, is an important and liberatory vision of queer sexuality and desire.

I think it’s clear from Swann’s writing that his understanding of love between men is not informed by the idea of an older man mentoring (i.e. grooming) a young boy, since Swann’s relationships are always between two adults (or people who would be considered adults in the ancient world), and not between much older men and younger, especially prepubescent boys. When Swann references Achilles and Patroclus in other novels, he does not refer to Patroclus as a boy, but instead reads them as adult male comrades-in-arms. And, as my quotations from Swann’s discussion of queer love in How Are the Mighty Fallen show, he explicitly refers to love between “men.” There is no hint, then, of Breen’s pederasty in Swann’s writing, and I rather think that, whether Swann knew who Eglinton was or not, he understood the book Greek Love as simply a historical account of a kind of male-male relationship that was common in the ancient, medieval, and early modern world. He also makes clear in his acknowledgement that the book was merely a starting point, the first suggestion he had that there was something more to David and Jonathan’s relationship, and that he sought out other texts and evidence himself.

It’s an awkward and uncomfortable connection between Swann’s beautiful, emotional, and important novel, How Are the Mighty Fallen, and the creepy work of an abuser like Breen. All I can do is name the connection and let Swann’s work speak for itself.

Parting Thoughts

In some ways, my project to read through all of Swann’s novels this year—this being my tenth essay, with the remaining six coming in the next two months—always felt like it was leading to How Are the Mighty Fallen, and not his final (and posthumous) published novel, Cry Silver Bells (1977). I began reading Swann with two of his later novels, Lady of the Bees and The Tournament of Thorns (both 1976), and while Lady of the Bees was fantastic, and Swann’s penultimate (also posthumous) novel, Queens Walk in the Dusk, about Dido, sounds equally interesting, How Are the Mighty Fallen stuck out in Swann’s oeuvre for its controversy and for being openly gay. That it was an openly queer version of a famous Tanakh story was interesting, but not as interesting as arriving at, what seemed to me, the culmination of a career spent writing about queer desire and male-male “friendship” on the downlow, with those relationships always expressly evident but subsumed into a love triangle in which heterosexual partnership won out. This is the case, for example, with both of those novels above that started my journey into Swann’s writing. How Are the Mighty Fallen promised to be explicit, controversially so, and that was exciting to me.

And, as I hope is evidenced by my reading of the novel above, How Are the Mighty Fallen is clearly a moving, motivated endorsement of queer love that renders it in beautiful, tender, albeit ultimately tragic language, and it is also a powerful critique of homophobia. At the same time, it smartly uses the language of the Tanakh/Bible itself to make its point, to make obvious the ancient truth of queerness in human society, so much so that the ostensible ancestor of Jesus, King David, could be said to have lived a life of many loves (sometimes dramatically so), but none of which reached the heights of that brief love with Jonathan. Within his own oeuvre, Swann also convincingly wrote the story of David into his wider world of the prehumans and fit it to his changing understanding of that world. How Are the Mighty Fallen is therefore gentler and kinder than some of his earlier work, possibly revising the Thriae into the non-villainous, supremely loving Sirens. It is also more concerned with death and the need to get things right in one’s life before dying, and it is interested, above all, in love as the means of getting life right, of fulfilling oneself. As I noted in my essay on Wolfwinter, by 1972 Swann was dealing with significant personal and health issues, including cancer. He died in 1976.

This shift in Swann’s writing to a greater emphasis on love and death surfaced first in Green Phoenix and was developed more fully in Wolfwinter. And here, in How Are the Mighty Fallen, when Swann is at his clearest about queer love, he focuses on themes of love and death to the exclusion of most other themes, notably that which animates most of his novels: the dialectical opposition between city and forest, civilization and nature, human and non-/prehuman. There is a bare hint of this theme in the fact that the Philistines, descended from the Cretans, represent the ideal of sexual egalitarianism practiced by the prehumans elsewhere in Swann’s oeuvre. But this is almost an inversion of the usual theme, where the Philistines of Greek descent represent both civilization and that which, in Swann’s typical narratives, civilization is opposed to. Their egalitarian view of sex and gender is contrasted, then, to the decidedly uncultured Israelites. But the Israelites, we know, will triumph and their mythologies—not just of David, but of their chosenness, of their singular god and his condemnation of “the sin of Sodom”—will spread beyond the deserts of the Levant and, through its appropriation by Christianity, inform the development of Western civilization more than the Philistines, who are remembered today mostly as a term for hostile, narrow-minded simpletons, anti-intellectuals antagonistic to aesthetic beauty and the value of art for art’s sake. Sound familiar?

For all my anticipation, How Are the Mighty Fallen was impressive more for its historical and cultural significance than for its writing or narrative. It has none of the crazy weirdness of, say, Moondust, with its evil telepathic fennecs, and only indulges briefly in the tenderness of its queer love story. I’m undecided on whether the Sirens and Cyclopes fit well with the story of the Israelites’ war with the Philistines, since in the end the only real value of the prehuman context is in explaining why Jonathan might be “special” in some way (not that he needed to be, to be loved so deeply and truly by a great leader and poet like David, but this is a fantasy novel!) or providing an explanation for Alecto’s witchery. But perhaps fitting these Greco-Roman and Israelite stories together was ingenious. After all, the events that led to the Trojan War epic cycle are the very same that led to the Philistines leaving “Caphtor” and settling in the Levant—these being the multi-century “collapse” of the late Bronze Age, a period of turmoil, war, natural disaster, famine, migration, and cultural and political shifts that affected the entire Mediterranean world and which is the backdrop for much of Swann’s “secret history” of the prehumans.

How Are the Mighty Fallen has moments of great beauty, it is a clear-eyed celebration and defense of queerness, and it is an interesting effort to bring together two very different kinds of story—but it is not a stunning novel, even if it is historically remarkable. It’s no Lady of the Bees or Wolfwinter or even the final third of The Weirwoods, but it is interesting, important, and incredibly worthwhile. Since How Are the Mighty Fallen is also connected implicitly to Moondust (since that novel ends with the birth of Boaz, the great-great-grandfather of David), and since the novel ends with the revelation that Jonathan had a Siren son with Alecto, I do wonder if Swann would have produced another story based on ancient Israelite mythology that would have created a loose trilogy similar to his Latium and Minotaur trilogies. Sadly, we will never know.

To get notifications about new essays like this one sent directly to your inbox, consider subscribing to Genre Fantasies for free:

11 thoughts on “Reading “How Are the Mighty Fallen” by Thomas Burnett Swann”