Will-O-the-Wisp by Thomas Burnett Swann. Corgi, 1976.

Table of Contents

Swann’s British Novel

Reading Will-O-the-Wisp

Parting Thoughts

Swann’s British Novel

Puritans and witch burnings. “Gray, gray, everything gray” Devonshire. Gubbings amidst the tors of Dartmoor. Fading memories of an Elizabethan golden age. A moral war over propriety and the soul of love. Woodpecker people, once worshipped as gods by the Celts, now hidden in obscurity and burdened by self-hatred. Welcome to the weird world of Thomas Burnett Swann’s England in the early seventeenth century, 1630 to be exact.

As I outlined in my essay on Swann’s The Not-World (1975), Swann wrote five novels set in Britain, two of which were loosely connected by the throughline of the Devonshire vicar and poet Robert Herrick, an author of mostly bawdy light poems, the most famous being “To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time” (1648), which begins, “Gather ye Rose-buds while ye may.” The Not-World followed Herrick’s descendent, Dylan, some 150 years after Herrick’s time, but Swann’s tenth novel, Will-O-the-Wisp, is about Herrick’s life and the love that bore the line that led to Dylan and his adventures in the Not-World outside of Bristol. Will-O-the-Wisp is also one of Swann’s several “poet” novels, alongside novels like The Goat Without Horns (1971) and Wolfwinter (1972).

Will-O-the-Wisp also gives us a glimpse at a new corner of his “prehuman” world of mythic creatures, usually of Greco-Roman legend, such as Fauns, Dryads, and Centaurs. But his British novels call for something else and incorporate local beliefs alongside Celtic myths to explore other prehuman peoples, such as the vampiric Drusii or the Water Horses, and the cultural-historical changes they undergo in Britain. Swann also occasionally connects his British prehumans to the Greco-Roman world, as with the Genii Cucullati, who are a slightly altered version of the Telesphori from his Latium cycle. Will-O-the-Wisp offers something completely new to Swann’s “secret history” of the prehumans: woodpecker people, known as Skykings but called “Gubbings” and feared by the people of Devonshire. Through the Skykings, Swann jabs a sharp critique at Christian morality and gives a very strange origin story for Puritanism, while commenting on the particular brand of epistemic violence that inheres at the intersection of Christianity and colonization.

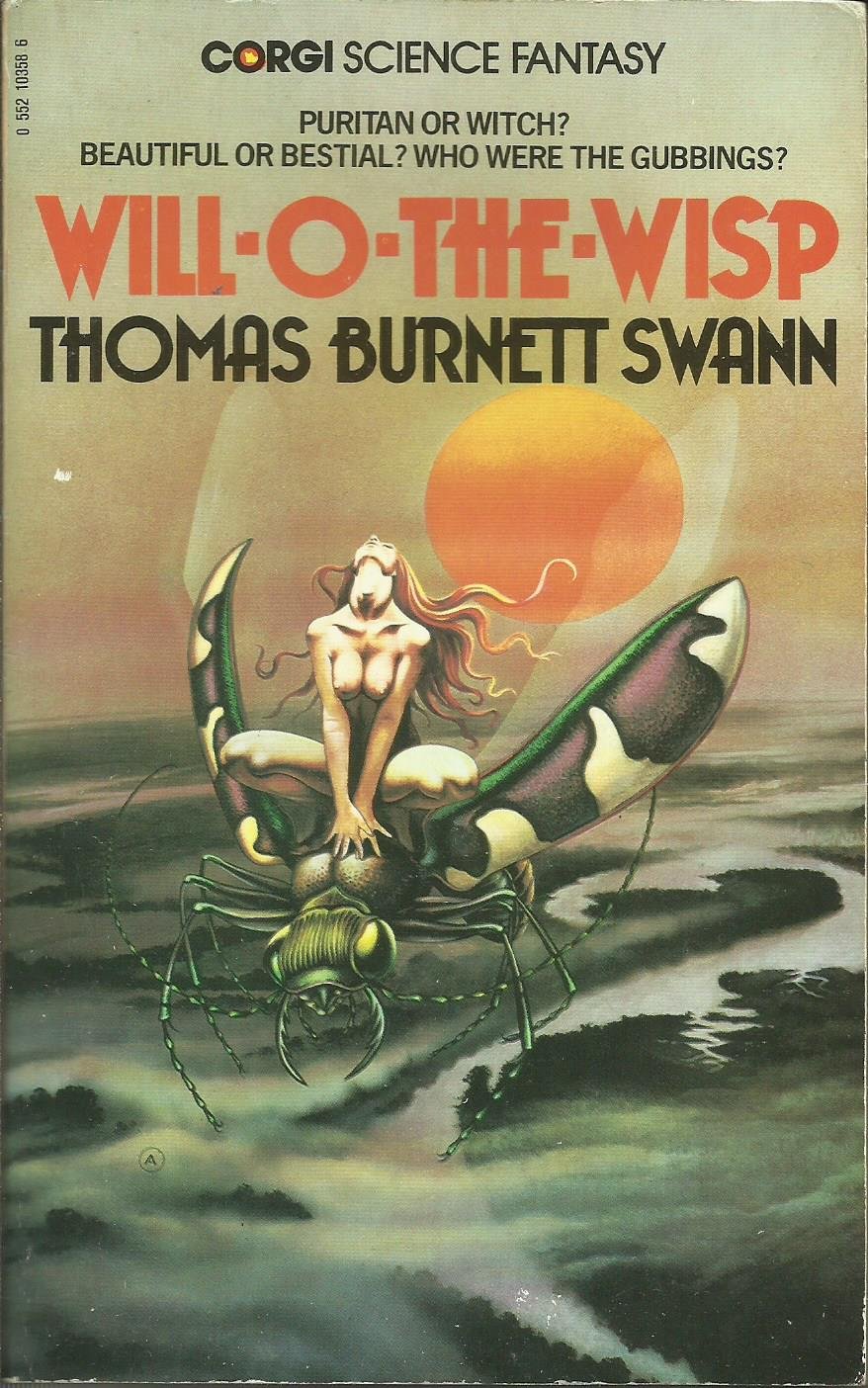

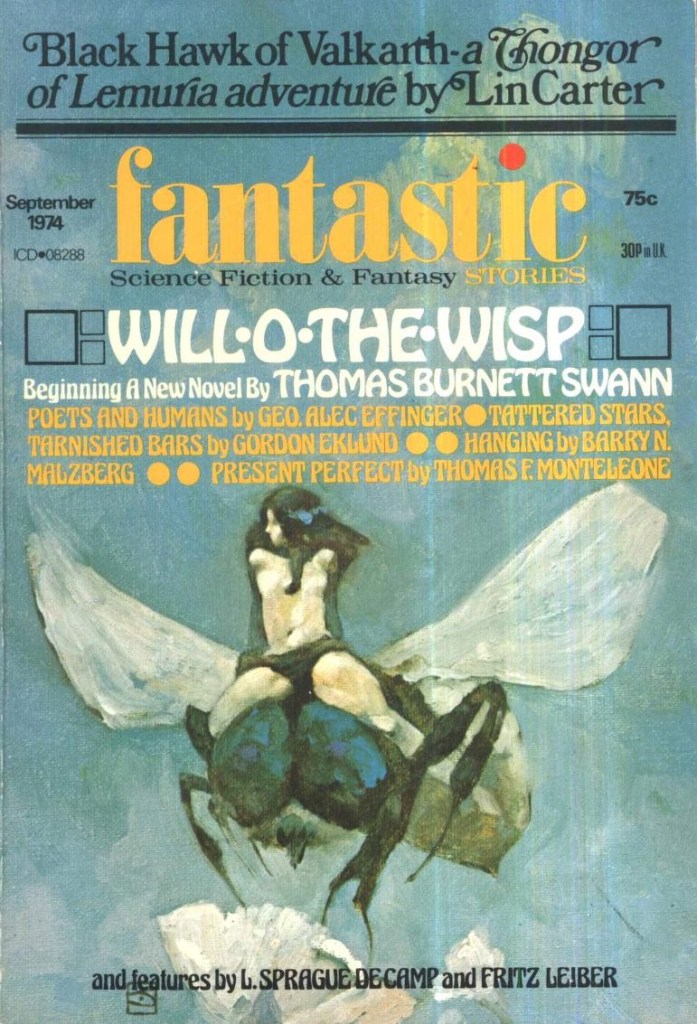

Though not published as a novel until 1976, the year of Swann’s death from cancer, Will-O-the-Wisp was originally serialized in two parts in the American sff magazine Fantastic in late 1974. After the great disappointment of The Not-World, Will-O-the-Wisp came as a wonderful surprise and I would rank it as one of Swann’s best novels, up there with Wolfwinter and Lady of the Bees (1976), and probably tied with The Weirwoods (1967). Swann’s novels were often criticized for being slight, for offering little beyond cutesy fantasy romance. A reviewer, Brian Griffin, commenting on Will-O-the-Wisp in The Vector Reviews Supplement (Feb. 1977), referred to Swann’s writing as “naive,” “soppy,” and “sloppy” and suggested readers look elsewhere, for example to John Buchan’s Witch Wood (1927), “[i]f you want revelation” (5). Griffin could not have been more wrong but fewer readers than usual got the chance to learn that: Will-O-the-Wisp was never published in the US and appeared only in the UK in a mass market paperback published by Corgi as part of their “science fantasy” line in 1976. This was Swann’s only novel never released in the US and it’s a damn shame that American fans of Swann had to miss this one.

Corgi, unfortunately, was lazy in their production of Swann’s one British-only novel publication. Not only are there dozens of typos in the novel, including dropped periods and commas and regular misspellings (none attributable to the differences in American and British spelling), but the cover is completely unrelated to the novel. And I don’t mean that it’s unrelated in content but nonetheless still evocative of the novel, such as Stephen Hickman’s cover of Lady of the Bees, a novel that features no such scene and no such woman as depicted on the cover, though the art gets across the idea of the novel anyway (see also his cover for the 1977 reprint of The Weirwoods). But I mean that Corgi’s cover, painted by Joe Staton, is totally and completely unrelated in the sense of having nothing to do with the novel’s content whatsoever.

This might, partly, be blamed on the magazine where the novel was first serialized, Fantastic, since the September 1974 issue that carried the first half of Will-O-the-Wisp featured a painting by Jeffrey Catherine Jones of a nude woman riding atop a giant bee. Swann’s story had top cover billing, in letters almost as big as the magazine’s title, and one could surmise, as one often does of sff magazine covers, that the painting was meant to accompany the story with the most prominent cover billing. Not so, in this case. The cover painting for this issue instead accompanies George Alec Effinger’s “Poets and Humans,” and the story was in fact written after the painting, inspired by it, at the request of the editor, Ted White. Even more confusingly, Jones had illustrated a previous Swann novel cover, Moondust (1968), and Swann felt that Jones was the only artist who ever “got” his stories (hence Jones was later asked by Swann’s friends to illustrate Swann’s only hardcover novel, Queens Walk in the Dusk, published posthumously in late 1977).

Corgi either didn’t care that the Fantastic cover illustrated a different story or they didn’t read Swann’s novel closely enough to realize there are no naked women riding bees (or, in Staton’s re-painting of Jones’s original, some sort of beetle) in the novel. I think it’s probably the latter, because whoever edited the novel didn’t do a great job. They even left in the multi-paragraph recap published at the beginning of the second installment in the original magazine serialization, in the November 1974 issue of Fantastic, which appears in Will-O-the-Wisp awkwardly at the end of chapter VI (pp. 82–83 in the novel, p. 56 in the magazine). This major oversight, paired with the negligent copyediting, compounded by the obviously unrelated cover art suggest Corgi cared very little, and Swann likely didn’t have the energy or time, given his sickness and the distance between him and the publisher, to try to push for a more carefully treated book It’s not clear when in 1976 the novel was published, so Swann very well might have been dead by the time it hit booksellers’ shelves in Britain.

It’s also not clear to me why Will-O-the-Wisp was never published in the US. It is, to me at least, very clearly one of Swann’s best novels. It’s surprising that neither DAW or Ace published the novel, given that they collectively put out five novels by Swann in 1976–1977 alone. Unless both publishers already felt they had too much Swann on their hands, crowding up their front list, I can’t understand Will-O-the-Wisp not appearing with a US publisher. I actually think it’s highly unlikely that either DAW or Ace would, after Swann’s death, have turned down another novel from his estate, since his death was referenced in his posthumous publications and Ace reprinted his earlier novels to capitalize on the fact that he had died. I suppose one could argue that the novel is simply too British, set in Devonshire and about an obscure British poet, but the complaint about location could be leveled at The Not-World and the obscurity of the poet at The Goat Without Horns. No, a new Swann novel, whatever its topic, would have been a boon to DAW or Ace. I wonder, then, if the problem was with the Corgi contract, which possibly made it unclear whether the book could be sold to a US publisher. This also seems highly unlikely! It’s possible that Swann’s estate—handled by his mother—simply didn’t want to pursue getting the book published in the US. But I simply don’t know.

Whatever the reason, it’s a shame Will-O-the-Wisp never reached the American sff market. But it’s also an interesting artifact and reminder of Swann’s popularity in the UK at the beginning of his career.

Reading Will-O-the-Wisp

Will-O-the-Wisp is a historical fantasy novel about Puritanism in early-seventeenth-century Devonshire that incorporates Devon folklore and gives a fantastic spin on the origin of the Puritans and the Gubbins, a pseudo-historical group of bandits who lived in and around Dartmoor—and it does all of this through a study of Robert “Robin” Herrick, whom Swann praises in an epigraph as “poet, vicar, and pagan,” a last bastion of fantastic pre-modernity in an increasingly modern and global age. Like all of Swann’s novels, it’s short, running to just 160 pages. And yet, where The Not-World felt baggy at the same length, with too little to occupy its scant pages, Will-O-the-Wisp showcases Swann’s talent for the short novel, as he weaves together real and fantastical histories told from multiple perspectives, and places at the center a sincere moral struggle and a joyous search for love and meaning in a harsh world. The novel is told from four perspectives that shift across five “parts” comprising roughly three chapters each. We follow the story from the perspectives of Nicholas, a questioning Puritan teenager and apprentice to his father, Michael, a harsh apothecary and devout Puritan; Stella, a Gubbing descended from royalty and ill-suited to life in the Gubbing community hidden in Dartmoor; Robin, the vicar and poet; and Aster, Stella’s nine-year-old daughter by her dead sailor husband from Exeter, Philip.

The novel begins rather drably in Cambridge, with Nicholas, a poor Puritan studying for the clergy, roomed with George, a wealthy dilettante who flaunts morality and knows the best places for a drink and a fuck. Nicholas is plagued by pagan dreams of naked women dancing around a Maypole and, submitting to what he views as these sinful desires (the better to know God’s grace, if he knows what true sin is like), he asks George to take him “roistering.” But Nicholas is a bit too pure for a good roister and when he flees the bar-cum-brothel in a panic, he is run over by a horse and his leg broken, whereon he is forced to return in shame to Devon, to apprentice for his father the apothecary. This rather perfunctory opening—focused unfortunately on the uninteresting character of Nicholas, whose Puritan worries seem hardly believable to an atheistic heathen like me—establishes important cultural and moral contrasts that animate the rest of the novel. Indeed, the intensity of Nicholas’s worries about sin and especially about sins of the flesh, are crucial to understanding Swann’s Puritans and the ideological work he does with them.

Will-O-the-Wisp in fact opens with a letter from Nicholas’s father condemning the new vicar, Herrick, as a heretic who quotes Catullus in his sermons and probably consorts with the Satanic Gubbings of Dartmoor. And from here flow Nicholas’s anxieties, for he liked Herrick instinctively—“There was a goldenness about the man. You expected to find him out-of-doors and not in church. Blessing the sheaves of the harvest, not the wine of communion” (11)—and he worries about his own proclivities to sin, while also doubting his father’s strictness of doctrine and interpretation of Christianity. But to him, born and raised a Puritan, he can’t help but feel tied to the moral framework espoused by his community. And above all he fears the body, for “an unclothed body was synonymous with temptation” (12) and the even intimation of temptation is practically a sin.

This fear of the body, of not just its potential carnality but its very physicality, this fear of the nature of being a person with a body, and by extension this fear of the natural world itself, is the core belief of Swann’s Puritans and the driving force behind the novel’s critique of religion. For Swann, as I’ve shown in all of my previous essays, was very much invested in free love and egalitarian gender relations between the sexes; his novels celebrated sexual choice and understood the free- and deep-loving prehumans—especially Fauns, Dryads, and Centaurs—as representing an ideal world violently overthrown by the rise of heteropatriarchal human civilizations, who brought oppression and hierarchy to gender relations. Swann takes this to a new extreme in Will-O-the-Wisp and offers Herrick as the last bastion of sexual egalitarianism—or what Swann calls “pagan” in his epigraph, the last remnant of a magical (imagined) Elizabethan age before the complete dawn of industrial modernity glimpsed in The Not-World—in conflict with Puritanism’s hyper-moralized fear of the body. There is a war here over the body: as a site of liberation and fulfillment or as a site of sin and shame.

When Nicholas returns to Dean Church (today called Dean Prior), he is tasked by his Puritan father with spying on Herrick and gathering evidence against him so the town’s small Puritan community can convince rest of the townspeople to burn Herrick for a warlock and a conspirer with the Satanist Gubbings. But Nicholas is enamored of Herrick and his magnetic pagan charm. He immediately takes to his potent admixture of sensitivity, poeticness, humor, and unadorned manliness, for Herrick is one of Swann’s classic archetypes: the sensitive, educated manly man who stands for nature and goodness. Herrick even defends a bear, a little creature being tortured by the townsfolk during a harvest festival, and in doing so he helps a mysterious girl and her mother, who appear from the moor and take the rescued bear back home with them. By this point, Nicholas confesses to Herrick that he was sent to spy on him, but Herrick is more father to Nicholas than the apothecary ever was, and so the two hatch plans to be fast friends forever—a friendship that transgresses against Nicholas’s moral community, but for which he is willing to go to Hell.

And Hell comes, in the form of a will-o-the-wisp. Herrick and Nicholas follow it into the moors, thinking it an invitation from the mysterious child and woman with the bear, whom they suspect to be Gubbings. And, indeed, they are led to the town of the Gubbings, a place where everything is gray and dismal. As Herrick notes, “How can evil be so dull?” The town is reminiscent of the White City of undead White Ones in Wolfwinter, its evil reflected in its aesthetic barrenness, only in Will-O-the-Wisp Swann takes that idea further and connects it directly to the Puritans. For the Gubbings, we learn, are the original Puritans.

Once, yes, the Gubbings were Skykings, wondrous woodpecker people, not unlike the winged Sirens of How Are the Mighty Fallen (1974) or the People of the Sea (mothpeople) of Moondust or the Thriae of the Minotaur novels. As Skykings, they were worshipped by the Celts as gods. But the Feather Blight came: they lost the ability to fly and their wings shrunk—like the Sirens and People of the Sea, who lost their flight, too, the former for offending Aphrodite and the latter for growing lazy in the luxury of power. Then the Christians came with the Romans. They convinced the grounded Skykings that they were fallen angels, like Lucifer, and must therefore be evil to their core. So the Skykings rewrote their holy book, the Book of Rejoicing, turning it into the Book of Redemption, they became the Gubbings, and they adopted a harsh Christianity based on mortification of the flesh, asceticism, and shame shame shame.

When the Christian world seemed most doomed, most in need of salvation, when a “bitch” queen (and witch, to boot), Elizabeth I, sat the English throne, the Gubbings brought their Christianity out of Dartmoor. And so the Puritans were born from a colonized people’s own self-hatred, a colonization of the mind by a cruel religious dogma that they sought in turn to inflict upon the rest of the world. The strict, modest dress of the Puritans hid the Gubbings’ vestigial wings and the colorful feathers on their backs, and in time they converted more and more to their cause, spreading across England, into Europe, and even bringing colonies to the Americas. It was the Gubbings who led the Pilgrims to Plymouth Rock on the Mayflower.

To protect themselves further, the Skykings encouraged the spread of the idea that the Gubbings were monsters and Satanists. To convince the locals, they abducted sinners by luring them into the moors with will-o-the-wisps (really, just Gubbings carrying lanterns!). Once in their grip, these sinners were tried by the Gubbings’ unforgiving courts and sentenced to crucifixion, their bodies sent back to their villages as a warning. The idea of the Gubbings does draw on some historical precedent. There was a pseudo-historical bandit group called the Gubbins that lived in and around Dartmoor, near Lydford Gorge (I’ve been there; wild garlic grows thick and fragrant in the spring, and bluebells carpet the forest floor), during the seventeenth century and which resulted in a sort of Robin Hood legend. This was taken up and elaborated by later historical fiction and adventure novelists.

Swann’s major source for Will-O-the-Wisp was Marchette Chute’s Two Gentle Men, a study of Herrick and another seventeenth-century poet. There is a mention—albeit presented as a plain historical fact—in Chute’s book of a popular version of the Gubbins legend, one shared in poems like William Browne’s “A Lydford Journey” (1644) and novels like Charles Kingsley’s Westward Ho! (1855), which recounts that “there grew in that place [Dartmoor] a tribe called the gubbings, men and women who lived like savages and would not even bring their children for baptism” (203). The legend, in its wildest form, even suggested that the Gubbin(g)s were pre-Christian Celts who had hid in Dartmoor since before the Roman conquest. This quoted passage is the only mention of Gubbin(g)s in Chute’s book but it proved a fruitful reference for Swann’s novel, with the Gubbings of Will-O-the-Wisp relying on the ideas spread by contemporaries like Browne to hide the truth that these original Puritans, these Gubbings, are in fact what they fear and hate most.

Herrick and Nicholas have been brought to Dartmoor as the newest sacrifice in the Gubbings’ pursuit of the mortification of the world’s sins. Herrick because of his bawdy poems and his flaunting of the Puritan idea that the body and sex should be things of shame, not celebration, and Nicholas for his refusal to turn on Herrick, for disobeying his father, for willingly entering the realm of the Gubbings when he believe they might be monsters and Satanists. But Herrick believed no such thing about the Gubbings and rejects the very idea that God could be so cruel, that God would be pain and punishment, not love and comfort—a critique of religion that is shared by Swann’s most controversial novel, How Are the Might Fallen. But Herrick and Nicholas are saved from crucifixion by Stella, the woman with the child and bear, who asserts to the Gubbings’ leader, the austere Judith, that Herrick has the right to a Trial by Rhyme. Basically, a seventeenth-century rap battle.

And so Judith and Herrick rap battle, each offering alternating lines, attempting together to complete a single, unified, ten-line poem on the idea of “redemption.” In his “Author’s Note,” Swann claims that the Trial by Rhyme poem was created piecemeal from Herrick’s poetry—a cento poem that nods to the breadth of Herrick’s oeuvre and Swann’s own poetic sensibilities (I was perhaps too unkind to Herrick in my previous essay, but in all fairness, Swann only quoted Herrick’s most ribald and annoying poems in The Not-World). As an aside, some readers might find it interesting that there is a reference to Ossian here. Stella claims that Ossian fought a Trial by Rhyme to defend his good name “against a man who accused him of conjuring Beelzebub” (58), and then quotes a passage about this from the Gubbings’ Book of Redemption. This could be a reference to the Irish poet-warrior Oisín, sometimes Anglicized as Ossian, or a sly reference to James Macpherson’s Ossian, the ostensible (and hoax) author of supposedly ancient Scottish Gaelic epic poetry “collected” by Macpherson more than a century after this novel takes place (Macpherson intended Ossian, I believe, to be quite literally the Scottish version of Irish myth’s Oisín).

Herrick wins the Ossian-inspired rap battle and he and Nicholas are saved from crucifixion but condemned nonetheless to live evermore with the Gubbings in Dartmoor, so they don’t reveal the Puritans’ secret. Stella, unsurprisingly, volunteers to house them. And, equally unsurprisingly, this leads to high romance and dramatic conflict. This is, for Swann, inevitable, because all of his novels are about love—not just about the hero getting the girl; no, never anything so prosaic or dismissive of the woman’s agency. Swann’s novels are about deep and abiding romantic and sexual love, sometimes framed as a love that conquers lust, but always understood as a kind of love that mutually benefits both lovers, without which they would be lesser people, not a man fulfilling a woman’s sense of self, or vice versa, but two people making one another more fully human through the gift of love.

I’ve argued before that Swann’s greatest interest seems to be in theorizing love and that he often does this by connecting his deeply affecting love stories to the larger thematic concerns of his novels—especially the theme of conflict between nature and civilization, the human and the nonhuman—and articulating them within the context of his interest in egalitarian gender and sexual relations. That is, his ideal loving relationships free people rather than bind them, and they are often explicitly understood to free lovers from the strictures of heteropatriarchal society. At the same time, they have just a dash of queerness (except How Are the Mighty Fallen, which is totally queer) and are never exactly feminist. Swann was, like all of us, a complex and contradictory person and he spent his short writing career—just over a decade, during which he wrote 16 novels—working through these ideas, sometimes for the better, sometimes for the worse.

As much as it is a story about Puritanism, or at least Swann’s interpretation of the Puritan’s beliefs, Will-O-the-Wisp is equally a story about the love between Herrick and Stella. Indeed, the two narratives are inextricable, for at the heart of Swann’s critique of Puritanism—and we can set aside the question of how historically accurate his representation of the Puritans is (the Gubbings’ obsession with crucifixes, for one, suggests that Swann didn’t have a strong grasp of Puritanism), since what Swann is really after is a a critique of any strict religious dogma that fears the sexual possibilities of bodies and human affection—is the question of love. Love between lovers but also divine love, of God for humanity, and vice versa. And Will-O-the-Wisp is one of Swann’s better love stories, with the relationship that grows between Herrick and Stella among his most tender, loving, and compelling.

Take, for example, the scene of their first kiss:

A silence fell between them. She felt: the next thing I say must be—significant.

Fortunately, there was no need for her to say anything, significant or trivial. He kissed and encompassed her at the same time, and he was much too quick to be graceful or artful; he was sudden, turbulent, and total; and the years did not tremble back to Philip [her dead husband]. It was now Robin, tomorrow and tomorrow. She held him and felt as if she were holding a great armful of sunflowers. Why did she think of him in terms of gardens? He was anything but delicate and floral. It’s because he’s the earth, she thought, its strength without its cruelty. I am the sky, though almost wingless; he is the summer countryside, with its wheatfields and its gardens, its sweet ruggedness and its rough sweetnesses. (94)

Swann masterfully interweaves passion and poetry, tenderness and intensity, earth and sky, the rugged and sweet, masculine and feminine—and the passage draws on a great many of his minor themes throughout his oeuvre, including and especially his love of flowers and the imagery of the garden, a place of care and creation in his work since the garden of his Minotaur Eunostos in his very first novel, Day of the Minotaur (1966). In this romance, too, Swann seems to be drawing strongly on The Weirwoods, for Herrick retreads the sexist idea of marriage as “capture” and of women as gleefully throwing the net. This is an idea thankfully disposed of by the end of The Weirwoods and Will-O-the-Wisp alike, as Arnth and Herrick respectively learn that a truly loving relationship of equals is not capture of one by another, the subjugation of man to woman (or vice versa), but the coming together of equals in a relationship that liberates both. Not the most radical idea, admittedly, but surprising stuff from a male fantasy writer in the 1960s–1970s, and almost certainly an outgrowth of the queer desire and undertones that circulate through much of Swann’s fiction.

But the Gubbings cannot tolerate the kind of relationship Herrick and Stella would have. For one, because all of the Gubbings envy Stella her beauty. (Swann does this kind of thing a lot, making his heroine the most gorgeous, voluptuous, desirable woman, the Helen of her time; moreover, Stella is based on Stella Stevens, Swann’s favorite movie starlet, to whom he dedicated this novel and several others.) For two, because they are unmarried, though Stella refused to consummate their relationship unless they are married. And for three, because despite her Puritanism, Judith is madly in lust with Herrick. So Herrick, Nicholas, Stella, and her daughter Aster must escape Dartmoor. The complicated plan goes awry, however, and they are captured by the townspeople of Dean Church, led by Nicholas’s father, Michael, the perfect example of a Gubbing living secretly among humans, spreading Puritan fear of a wroth God to cover his own shame for having wings and feathers (Nicholas is one, too, though he lacks wings and feathers).

In a truly tense, dramatic showdown that is some of Swann’s best writing, the protagonists are led to the stake and tried for witchcraft. Just as it seems they might win the trial, Michael rips off Stella’s clothes and shows her wings—no longer mere stumps, they have grown large and angelic, fiery red, thanks to the love she and Herrick share (this echoes how David’s love for Jonathan helps the latter’s tiny Siren wings grow large enough to fly him to the Celestial Vineyard in How Are the Mighty Fallen). Stella accuses Michael and other Gubbings hidden among the townspeople of having wings, too, but as the novel’s favorite saying goes, no one ever suspects the first accuser. The townspeople laugh at the idea that Michael could be a Gubbing, but a gyrfalcon—possibly the reborn soul of Stella’s dead husband—descends from the sky, rips Michael’s Puritan clothing open, and reveals the apothecary’s wings and feathers. A frenzy ensues as the townspeople turn on one another, everyone ripping everyone else’s clothes off, resulting in some dozen Gubbings being killed. But Herrick, Nicholas, Stella, and Aster are spared. The townspeople march into Dartmoor and burn the Gubbings village, but not before the Gubbings escape: “Perhaps they would find a ship and sail to Plymouth or found a new colony and shame the Indians out of their loin cloths and into trousers” (155).

The novel ends with Herrick embraced by the town, Stella living as his secret wife, and Nicholas and Aster being raised together as their children. The novel has to offer some unbelievably silly reason as to why Herrick can’t openly have Stella as his wife, because it would shame him or something since all the townspeople know she’s got wings… It doesn’t make narrative sense, but Swann explains in his “Author’s Note” that, in reality, Herrick never married, but he did have a live-in housekeeper, Prudence Baldwin, who stayed with him for decades, followed him into exile during Cromwell’s Commonwealth, and returned with him to Dean Prior after the Stuart Restoration. Herrick also wrote several poems about Baldwin and Swann surmised, given the general tenor of his poetry, that Herrick and Baldwin must have been lovers. In essence, then, Will-O-the-Wisp is Swann’s historical fantasy novel shipping Herrick and Baldwin. It’s an AU fanfic for the very niche Herrwin? Bladrick? ship.

Parting Thoughts

Will-O-the-Wisp is an impressive novel, badly done by its unrelated cover, and sadly underserved by a limited release only in the UK. But it’s easily one of Swann’s finest novels, a lofty addition to the “secret history” of the prehumans with its wholly unique woodpecker people, and a smart, sharp attack on the destructive powers of Christianity and colonization.

This latter point is subtle but pairs well with the thrust of Swann’s critique of colonialism in the otherwise wholly unimpressive novel The Not-World. Swann may be offering a caricatured version of Puritanism familiar to every American schoolkid, but he uses this simplified caricature of a violence-stoking, hyper-moralizing Christian sect to demonstrate the horrific tragedies wrought by Christianization and colonization. First, the Skykings lost their wings. Then, the Roman Christians made them believe their wings were a sign of their evil. And finally, as the self-hating Gubbings, they exported a new, more virulent strain of Christianity, founding colonies so as to better infect the “New World” with their ancient self-hatred. Swann peels back the layers of colonial and Christian violence—physical, epistemic, and moral—and he does so, as usual, in a wildly, almost ridiculously, inventive story that explains woodpecker people hiding in Dartmoor as the origin of the Puritans, and features an obscure seventeenth-century writer of bawdy light poetry as the sensitive hero made whole by the beautiful, intelligent heroine who hid her wings and pretended to be his maid.

Like the best of Swann’s novels, Will-O-the-Wisp shouldn’t work, but it does. It’s chaotic, poetic, at times achingly beautiful, and though seemingly overwrought in its caricature of Puritanism, the novel hammers the violence of Christian moralizing against love, sexuality, and the body with a pain that is palpable.

To get notifications about new essays like this one sent directly to your inbox, consider subscribing to Genre Fantasies for free:

5 thoughts on “Reading “Will-O-the-Wisp” by Thomas Burnett Swann”