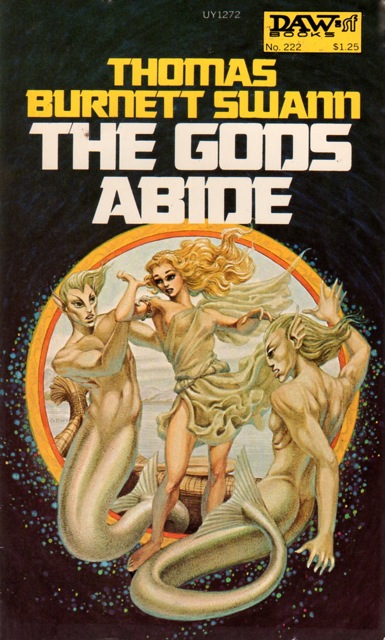

The Gods Abide by Thomas Burnett Swann. DAW Books, 1976.

It is equal parts fascinating and frustrating to read an author whose oeuvre fluctuates in quality as precipitously as Thomas Burnett Swann’s does. What’s fascinating is that so much of the tone, ideas, settings, characters types, and themes are so similar across his novels, but they manifest to such diverse and at times perplexing effects. In one novel, Swann might offer a sensitive, nuanced critique of masculinity, patriarchy, and religion, complete with characters who are equal parts serious and silly, but always sincere, and in another novel he might, with similar characters and plots, but lacking the same level of poetic grace and critical nuance, gesture at similar themes but write something downright misogynist and disappointing.

Such was my experience of the previous Swann novel I read in this read through of his 16 novels: The Minikins of Yam (1976), Swann’s eleventh novel and easily one of his worst books. Swann’s twelfth novel, Lady of the Bees (1976), the first of his I read, was by stark contrast one of his best novels—if not the best—despite dealing with very similar themes of gender and sex(uality), and his subsequent and thirteenth novel, The Tournament of Thorns (1976), was another weak novel (less bad than merely forgettable, aside from the ending, which is truly impressive). And now I’ve arrived at Swann’s fourteenth novel, published more than half a year after his death from cancer in May 1976: The Gods Abide. And, if you’re following the pattern, then you can probably guess that this second of his four posthumous novels and the last of his five published in 1976 alone, is in fact an impressive work of historical fantasy, this time set in late-Roman Italia and Britannia during the reign of Constantine and amidst the empire’s legitimation of Christianity.

Not only is The Gods Abide an impressive novel, which expertly uses its scant 160 pages to tell a story that seems to unfold on an epic scale, but it is also an important key to Swann’s entire oeuvre and, though not his final novel, it works as a thesis statement explaining how he understood, by the end of his life, the critical value of his “prehuman” tales about the death of mythological beings at the hands of human civilization and the attendant dissolution of egalitarian gender and sexual relations and humanity’s relationship with nature. In short, here at the end of his life, in one of the last novels he wrote, The Gods Abide gives us Swann’s best summation of his argument—outlined over his 16 interrelated novels, the entirely of his output as a novelist—that human civilization was a tragedy that wiped away an older, more equal, more gentle world peopled by beings we only remember as myths and legends. What’s more, The Gods Abide makes crystal clear, more so than anywhere else in his oeuvre, that masculinity, urbanization, Christianity, and violence were the tangled forces behind that tragedy. The novel boldly argues that Christianity’s originary vision of loving kindness was manipulated by men to attain power, suppress women, and end what Swann often articulated as the fundamental queerness of paganism.

The Gods Abide tells the story of two youths—one, Dylan, a Roane (seal-person) orphan from Caledonia captured and enslaved by Romans (and now escaped), and the other, Nod(otus), a Corn Sprite adopted into a Roman family ruled over by a dictatorial Christian patriarch, Marcus—whose narratives intertwine within the harsh realities of life under the Roman empire at a time of religious turmoil as, in Swann’s telling, the newly legitimized Christians push the legitimacy of their religion with blade and torch to the detriment of the remaining pagans and the few surviving prehuman peoples. All of Swann’s novels are about the prehumans and constitute a “secret history” of their slow, millennia-long destruction by human civilization and their survival in the interstices of urban human life, often at the edges, in the feared forests or on far away islands. Many of Swann’s novels are set in the late Bronze Age, but a third of his novels take place in much later periods, from the medieval to the early modern on down to the end of the nineteenth century. And several, like The Gods Abide, take place during the flourishing of human empires in and around the Mediterranean. The Gods Abide, like Will-O-the-Wisp (1976), focuses on the role of Christianity in victimizing the prehumans, demonizing them, and exacerbating their destruction.

Set in the early 300s CE, Swann’s novel sensationalizes the transition from paganism to Christianity in the Roman empire, showing the Christians—as in Will-O-the-Wisp—to be unrelentingly violent and hypocritical. The Gods Abide does not shy away from its harsh critique of Christianity as a tool for power consolidation wielded by men, driven by masculinity, and ignorant to the rhetoric of love celebrated by the Jesus of the Gospels. Swann’s Christianity is the ultimate force for destroying what his “secret history” of the prehumans has codified as an older, more egalitarian, more loving, gentler time represented by the prehumans and their cultures—a Golden Age reduced to one of Tin. And the story he tells of Christianity’s rise and spread is a surprising one that reveals the pettiness and viciousness of the Christian God.

In many ways, The Gods Abide is a very typical Swann novel. Two youths representing different kinds of masculinity, one macho but gentle (Dylan), the other gentle and worldly (Nod), are thrown together by a crisis that comes into existence through an external force that seeks the destruction of Nature. This external force is not a direct threat to the two youths, but a threat to their friends and love interests, the Corn Sprites Stella and Tutelina, who are the novel’s representation of Nature and egalitarian values of gender and sexuality. (As an aside, this version of the Corn Sprites is radically different from Swann’s earlier portrayal of them as tiny, bee-like, fairy-esque people in The Weirwoods (1967).) Stella and Tutelina are fecund fertility spirits, as well as sex workers, and they host an orgy for a pagan Roman festival. Nod and Dylan are educated in the ways of sex and confront their own desires, traumas, and identities through this miraculous experience. But Nod’s adoptive Roman father, Marcus, leads a gang of Christians to burn the orgy out, and everyone escapes with the help of Stella’s magic.

The former slave Dylan then uses his Roane skills to take them away from the town of Misna (which I think is supposed to be Misenum?) by boat, going via an underground river that is also the Styx, where they encounter giant forests of mushrooms, the guardian of the Underworld, Cerberus (who is actually a voracious caninomorphic Dog Rose), and a demoness, Genita Mana, who turns out to also be Marcus. The demoness uses the form of Marcus to sow seeds of hate and violence, with Christianity as her tool, and she proposes that the Desert King (Swann’s name for the Christian God) must approve of this, otherwise he’d strike her down. The four prehumans escape Marcus but he tracks them all the way to Caledonia and then Britannia. Along the way, Dylan, Nod, Stella, and Tutelina fight several battles, encounter Sirens and Tritons, have an orgy or two, and eventually make their home in the giant primordial Celtic forest, the Not-World, first glimpsed in the (later-set) novel The Not-World (1975).

The novel ends with the rather shocking revelation that Nod’s adoptive mother and wife of Marcus, Marcia, is actually the Mother Goddess herself—a goddess at the center of Swann’s prehuman secret history, the primordial feminine figure who is manifested in the many goddesses celebrated by his novels, and whose religion is, essentially, love. Marcia reveals that Stella is really Proserpine/Persephone and she must return to the Underworld to dwell with Pluto, leaving her lover Dylan behind. And Tutelina is an equally ancient prehuman who lived during Aeneas’s time (I believe she was a Dryad in The Green Phoenix (1972)). Marcia tells the story of Christianity as one of manipulation by corrupting forces, saying that Jesus was in fact the son of the Desert King by Mary, a human, but that Jesus ignored his father’s violent, warring religion in favor of the gentle loving religion of the Mother (called Ashtoreth in those days, a major element of the novel How Are the Mighty Fallen (1974)). In payment for this betrayal, the Desert King allowed Jesus to be brutally killed by the Roman and manipulated the religion that sprang up among his followers, principally through the woman-hating Paul and demons like Genita Mana/Marcus, to spread his power across the world. The novel ends here, rather abruptly, with the suggestion that Nod, Tutelina, Dylan, and the Siren Mara will live life after life, reborn perhaps eternally, in the last earthly paradise of the Not-World. The ending is melancholy, lit by the dimmest possibility of hope and survival, but in the context of Swann’s secret history it is a small, sad kind of hope reminiscent of the ending of The Weirwoods and Wolfwinter (1972).

Like all of Swann’s novels, The Gods Abide blends his characteristic sweetness, which some have derided as saccharine, with the harsh violence and melancholy of the “dying world” of the prehumans. He blends cuteness, innocence, and sweetness with violence, trauma, and tragedy. I’ve always found this to be an endearing outcome of Swann’s worldview, since he seemed to believe deeply in the paradisiacal, sexually liberated innocence of his love-loving prehumans but also knew that, had such a world existed, it was obviously long dead and gone—and his novels sought to answer why. In many ways, Swann offers a 16-novel exegesis of the Gravesian theory of the sacred feminine matriarchal prehistory that was ultimately supplanted by patriarchy (though I think Swann’s vision is a good deal more feminist and queerer), and his novels make explicit the operation and reproduction of patriarchal values (though, as I’ve noted, he didn’t always succeed in this regard). The Gods Abide ties everything together, names Christianity as the final force of the prehuman world’s demise, and articulates a theory of how Christianity “lost its way” between its story of Gospel love and the reality of Christianity as Swann understood it.

Moreover, the novel inventively interweaves a huge array of myths from Roman, Greek, Celtic, Judaic, and Christian traditions, and more than all of Swann’s novels it is, I think, cognizant of the full range of his prehuman tales, with references to nearly all of the prehumans narrated in his previous novels. This is sort of a rarity, since Swann’s novels tend to remain pretty isolated in their discussion of the larger prehuman world, giving only glimpses here and there of what exists beyond the narrative, but The Gods Abide is unusually reflective on the larger project of the prehuman secret history that occupied Swann’s career as a fantasist. I wouldn’t go so far as to say it’s his best novel, since frankly I could do without Dylan and his faux Scottish accent, and I don’t find either Dylan or Nod particularly compelling as characters, but The Gods Abide is among his best and might be his most important novel for the reflection it offers on Swann’s literary career.

The Gods Abide makes clear Swann’s project not just to write mythic historical fantasies about the rise of civilization and patriarchy, about the loss of egalitarian modes of gender and sexual relations, and about the tragic, poetic beings who witnessed these tragedies—but to use fantasy as a tool for political critique, as a way of reimagining the possibilities for social, gender, and sexual being, and for identifying the ideological forces that delimit those possibilities. The Gods Abide is key to any critical reading of Swann, all the more impressive for having been written so near the end of his life, in the midst of illness and cancer treatment, at a time when he was furiously writing novel after novel.

I have no doubt that Swann felt himself to be like Stella, revealed as Proserpine, called to the land of the Dead before those who loved him would wish to see him go. But as Stella reminds Dylan, when she goes willingly back to be with the lonely but just Pluto, and as Swann instructs us: “What is hello without goodbye?” (158).

To get notifications about new essays like this one sent directly to your inbox, consider subscribing to Genre Fantasies for free:

3 thoughts on “Reading “The Gods Abide” by Thomas Burnett Swann”