Queens Walk in the Dusk by Thomas Burnett Swann. Heritage Press, 1977. Latium 1.

As his only hardcover book, Thomas Burnett Swann’s fifteenth novel, Queens Walk in the Dusk, is unique. Like many mildly successful sff writers of the latter half of the twentieth century, Swann’s career—which included sixteen novels and two story collections, along with a dozen short stories—was largely defined by the mass market paperback. All of Swann’s novels were published in this format by Ace (6 books: Day of the Minotaur, The Weirwoods, Moondust, The Forest of Forever, Lady of the Bees, and The Tournament of Thorns), Ballantine (2 books: The Goat Without Horns and Wolfwinter), DAW (6 books: Green Phoenix, How Are the Mighty Fallen, The Not-World, The Minikins of Yam, The Gods Abide, and Cry Silver Bells), and Corgi (1 book: Will-O-the-Wisp), and all received painted covers by popular sff artists, like Gray Morrow and George Barr. But Queens Walk in the Dusk was published in September 1977, more than a year after Swann’s death, by the specialty hardcover publisher Heritage Press in a small print run of just two thousand books—and it was illustrated by Swann’s favorite cover artist, Jeffrey Catherine Jones.

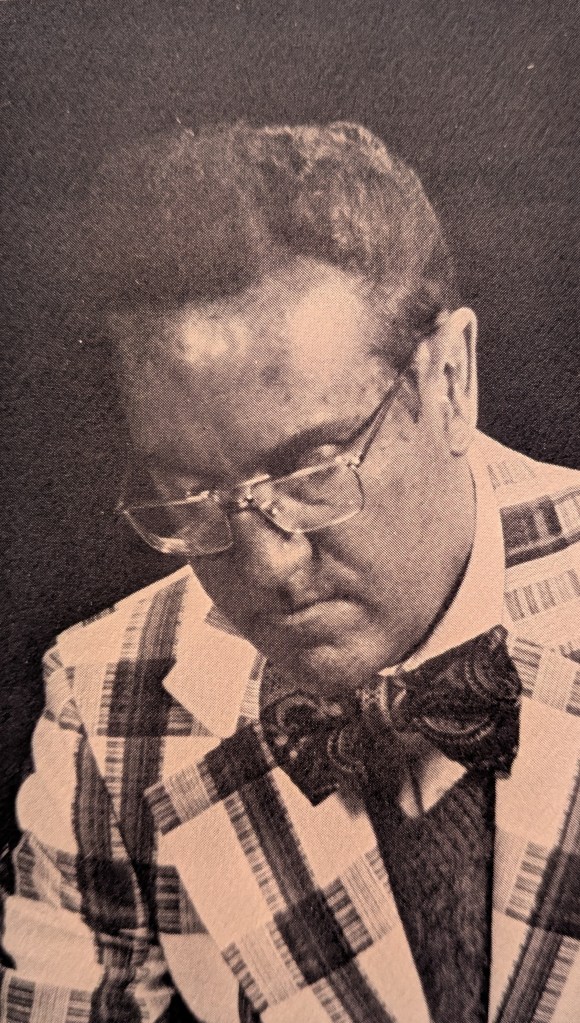

The hardcover publication of Queens Walk in the Dusk was a dream of Swann’s and was arranged by his friends and colleagues, particularly Gerald W. Page, a prolific fan writer who corresponded with Swann for years and met him on multiple occasions. Page provided a seven-page essay on Swann’s life and fiction, and claims that “a hardbound first edition was a dream of his” and that Swann was “very conscious of the fact that all his novels had been published in paperback editions” (133). (Page’s essay is one of three scant sources on Swann’s life, there others being a 1974 interview published in the fanzine The Tyrean Chronicles and a 1979 pamphlet by Robert A. Collins, Thomas Burnett Swann: A Brief Critical Biography and Annotated Bibliography, which is not available online.)

Queens Walk in the Dusk not only brought Swann into hardcover but the book once again paired him with the artist Jeffrey Catherine Jones, a prolific fantasy cover painter in the late 1960s and early 1970s, who later came out as a transwoman (she initially went by Jeff Jones and by Jeffrey Catherine Jones after transitioning). Jones had painted the cover of Moondust (1968) and, according to Page, Swann “felt that Jones, alone of all the artists who had illustrated his works, shared the vision he had seen, and it pained him that Jones was not used more frequently” (133). (See my comments on the cover of Will-O-the-Wisp, which has a strange, tenuous connection to Jones.)

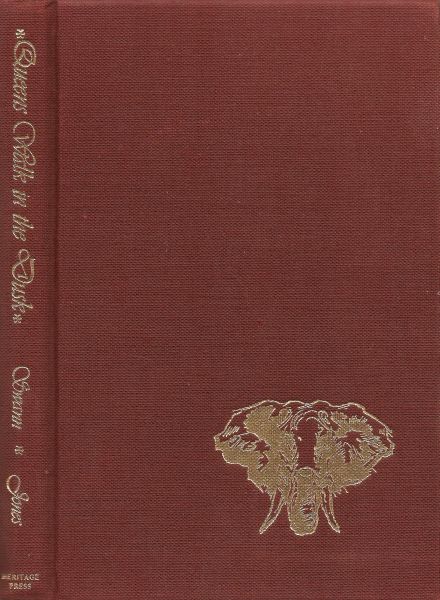

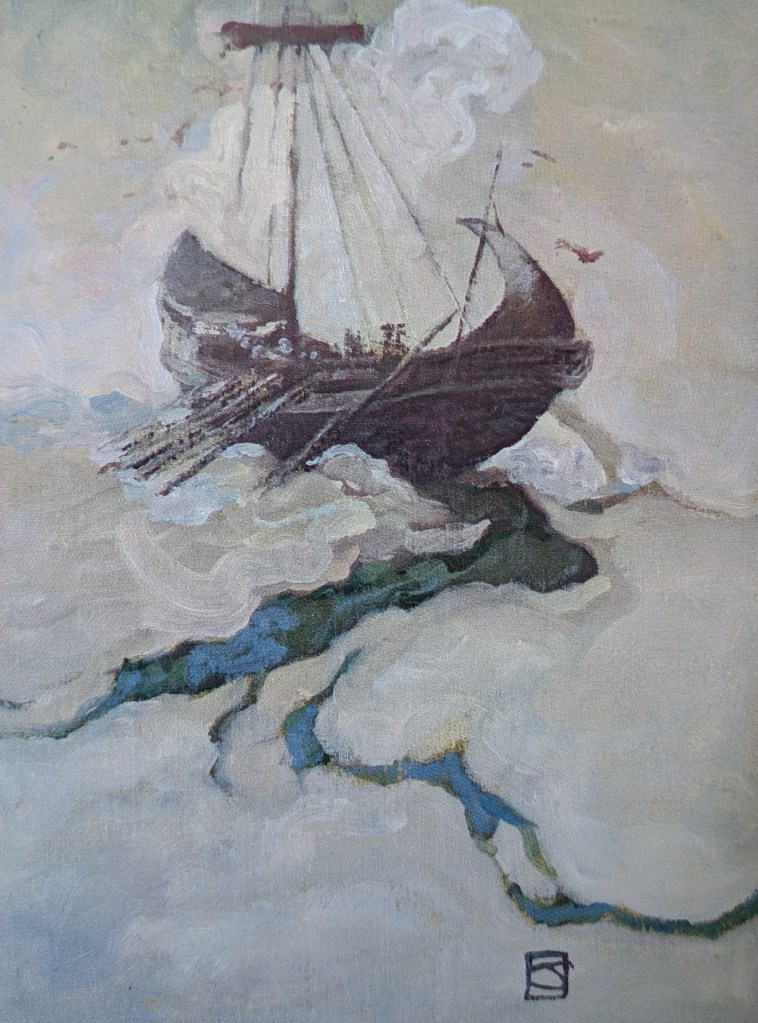

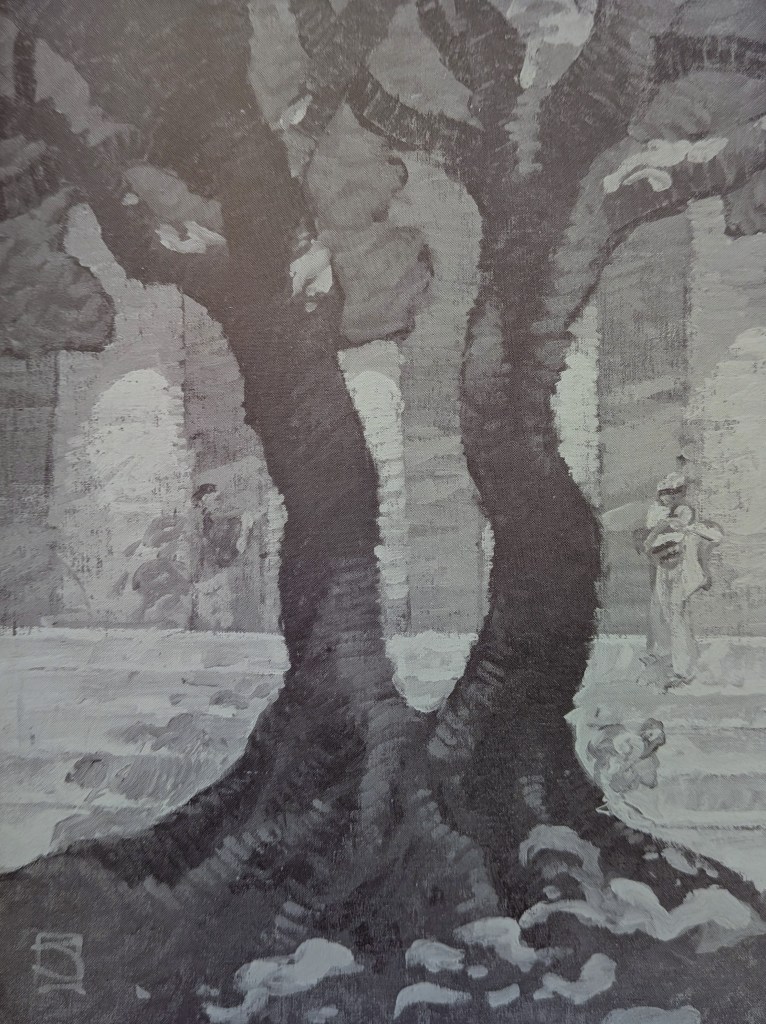

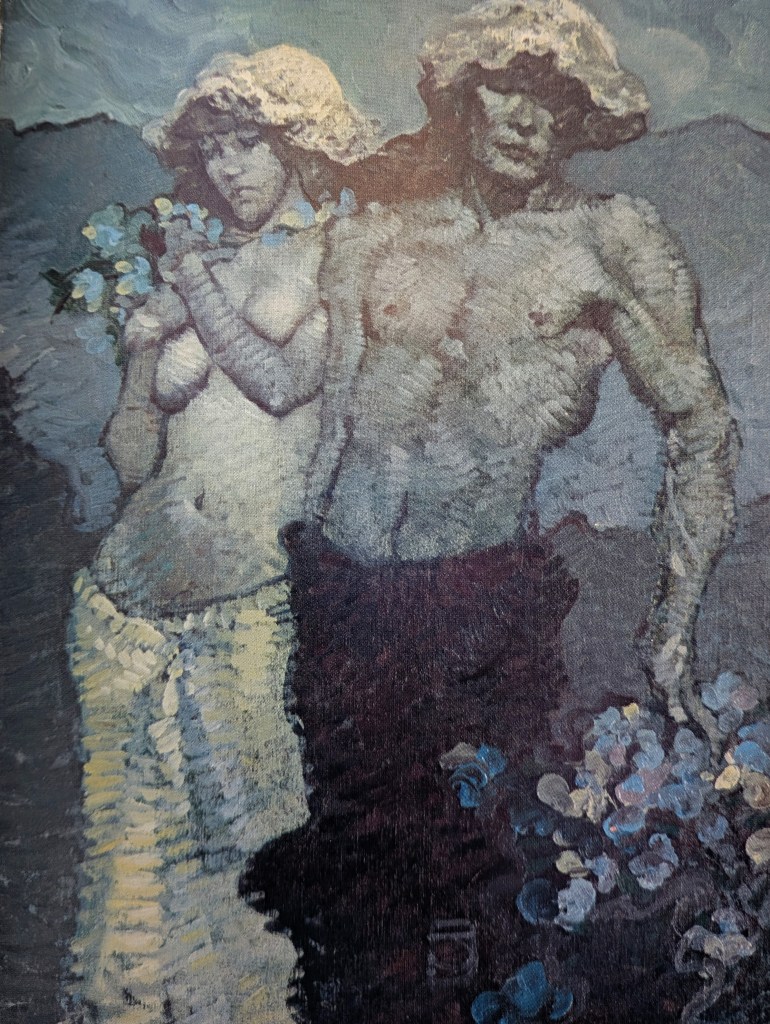

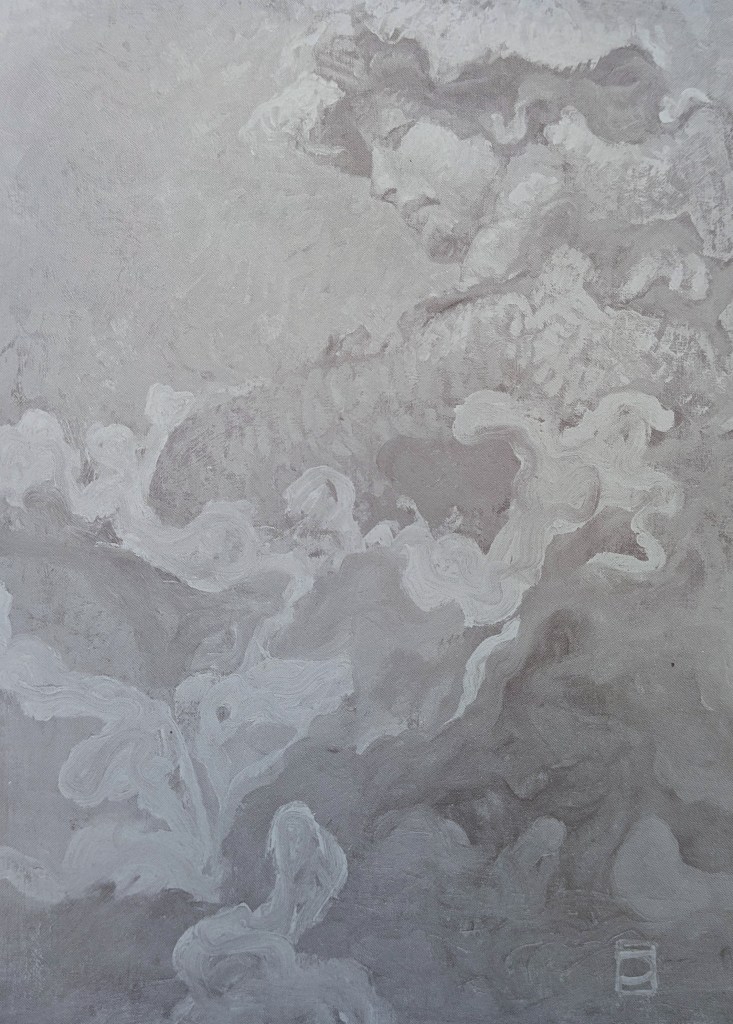

Though Queens Walk in the Dusk did not receive an illustrated dust jacket and was instead bound in a maroon cloth clover with a gold-inlay design of an elephant’s head on the front, ten illustrations by Jones appeared inside the book. One, for the endpapers, depicted the lonely elephant king Iarbas in austere greyscale. Another, across from the title page, was a cutout portrait of Iarbas’s head, used mostly as decoration. But the real beauty of the book and the real value of Jones’s contribution to Swann’s novel is the eight nearly full-page paintings that were hand-glued into the two thousand editions of the novel. The paintings are heart-breakingly beautiful and I have been unable to find reproductions of them anywhere online, so I’ve carefully photographed them all and provided them in the gallery below.

Jones’s work in these paintings is nothing short of brilliant; that said, I don’t think they fit the novel well, if only because Swann incessantly and uniquely mixed the borderline cute (or the “saccharine” as many of his detractors said) with the serious, heavy, and melancholy. Jones’s paintings capture the latter but there’s no place in his greyscale and bluescale images for the rest of Swann’s vision. They are beautiful, but sometimes feel out of place with Swann’s novel, making for an awkward contrast with the pages they sit across from. This issue of contrast also has to do with the fact that none of them, aside from the first, depict scenes from the novel. They are, instead, loving impressions of the late writings of an author who died too early and who felt his novels perpetually underserved by the cover artists chosen to present his books, visually, to the sff world.

If Queens Walk in the Dusk’s publication in hardcover and its accompaniment by paintings from Swann’s favored artist were intended to reflect in material form the weight and sincerity of Swann’s vision for his mytho-historical fantasies, then the effort was a success (leaving aside the numerous typos Heritage Press left in the book, including occasionally using the wrong name for a character). Moreover, the novel itself was well-chosen to fulfill Swann’s dream of a hardcover first edition, as Queens Walk in the Dusk is among his finest novels—an impressive feat, since Page says it “was probably the last of Swann’s stories to be completed” (only Cry Silver Bells was published later, his last novel, and it’s unclear, from everything I’ve read, how it made its way to DAW at such a late date, a full year after DAW’s previous novel by Swann, so I can’t say whether Cry Silver Bells was written before or after Queens Walk in the Dusk).

The novel is technically, in only the loosest sense, the first in a series of books about Vergil’s Aeneas and the founding of Rome. Fans and critics took to calling these three novels—in storyworld order: Queens Walk in the Dusk (1977), Green Phoenix (1972), Lady of the Bees (1976, expanding a 1962 novella)—the Latium trilogy, after the ancient name for the region where Rome was founded. Queens Walk in the Dusk tells the story of Vergil’s Aeneas, after leaving his home of Troy, crashing on the shores of Queen Dido’s newly founded Carthage; Green Phoenix tells of Aeneas’s coming to Italia after leaving Carthage; and Lady of the Bees describes the founding of Rome by Romulus (a descendant of Aeneas). But none of these stories is really about Aeneas, or at least they are only about him insofar as Aeneas is Swann’s window into the lives of women: Mellonia the Dryad in the case of Green Phoenix and Lady of the Bees, and Dido in Queens Walk in the Dusk. Indeed, for Swann, myth-histories are always a jumping off point for telling his larger “secret history” of the prehumans, or the mythological beings, such as Dryads and Fauns and Centaurs, who were driven into obscurity and eventually extinction by the rise of human civilizations.

The Latium trilogy is less a trilogy than a set of duologies tied together by a shared middle novel, Green Phoenix. Queens Walk in the Dusk, having been written several years later, is in many ways a revision of Green Phoenix’s characterization of Aeneas and Dido’s love and of Ascanius, Aeneas’s son. Queens Walk in the Dusk can be read as redressing a slight Swann made against Dido in Green Phoenix and about which he felt badly, since in that novel Dido is presented as a jealous, misguided woman who tried to keep Aeneas from his destiny of founding Rome. The Ascanius of Green Phoenix (a thoroughly unlikable character) scorns Dido even as Aeneas describes her more kindly: “An unhappy woman who mistook summer for spring and wanted to stop the drip of the water clock, the shadows of the sundial” (59). But the description of Dido in the earlier-written, later-set Green Phoenix shares no resemblance with the Dido of Queens Walk in the Dusk; nor does Ascanius, who is dramatically reimagined as a younger, kinder boy in Queens Walk in the Dusk; nor do Aeneas’s feelings for Dido, which in Green Phoenix are shrugged off as an unequal romance but in Queens Walk in the Dusk is presented as life-affirming for both Aeneas and Dido. The shared characters of both novels have little in common beyond their names, with the exception, perhaps, that in both novels Aeneas is a gentle, melancholy man who would rather be bard than hero, father than founder of a new Troy, and yet is doggedly driven by the gods-given destiny laid before him.

If a reader were to treat the so-called Latium novels as an actual trilogy, and were to read it in storyworld order, it would make very little sense. I think it’s better to understand Swann as a writer whose stories are interconnected, yes, but only superficially and thematically. He didn’t feel the need to create a sense of careful storyworld continuity from novel to novel. What he wrote in earlier novels he gleefully changed in later books as the mood suited him or as his plots demanded, so that, for example, the Fauns in early Swann novels are mischievous cretins barely worthy of attention, they are rapacious and willing to betray other prehumans, but in later novels the Fauns are reimagined as the heart of prehuman communities and they become potent metaphors for the shortness of life and the depth of love possible in so short a life. In this way, in his willingness to productively rewrite his own earlier iterations of mythic peoples and characters and narratives, Swann’s prehuman story cycle—which encompasses all of his novels—was wilfully inventive and shared much in common with the way ancient writers put their own spins on myths without worrying about whether their new tellings fit perfectly with earlier versions.

Queens Walk in the Dusk is a rather simple story but its simplicity allows Swann to focus on the emotional dynamics between Aeneas, Ascanius, Achates, Anna, Dido, and Iarbas. In brief, the novel begins with Dido in Tyre and her fateful marriage to a Glaucus, a prehuman like a Nereid (water nymph) or a Roane from The Gods Abide, but which is entirely new to Swann’s storyworld (he doesn’t explore how they are different from these other two or from Tritons or Sirens—his water-people seem to have expanded in his last three years!). But her new husband is killed by her brother Pygmalion, king of Tyre, and she eventually flees the Phoenician city-state, stealing half of Tyre’s fleet, and founds a new city where she, the humble queen beloved by her people, and a half-Nereid herself, daughter of Electra, can create a better life for all. Dido meets her match in Aeneas, whose ships, after fleeing Troy and hopping around the Great Green Sea for seven years, smash upon Carthage’s shores after a storm. The Trojans are taken for ivory hunters by Iarbas, king of the elephants, but Aeneas’s son Ascanius intervenes, revealing his psychic ability to commune with animals, and befriends Iarbas. (As an aside, Iarbas was a real mythic figure, a Berber king in The Aeneid and, before that, considered by the Romans as one of the Berbers’ ancient gods, who connected their mythology to the Romans’ via a story about Jupiter.)

Of course, a deep romance develops between Dido and Aeneas. Both are leaders wholly devoted to their people, willing to sacrifice personal desires and joys to ensure their people’s safety, happiness, and growth. Aeneas is tormented by his failures at Troy and by the death of his wife, Creusa, but Ascanius is in want of a happy father and mother, a family, and so plots to ensnare Aeneas and Dido into a wedding. But we know from Vergil’s epic that Aeneas and Dido are not a happily ever after, much as, it would seem, Swann wants them to be. The conflict in Queens Walk in the Dusk has everything to do with the elephant king Iarbas. Like Aeneas and Dido, he lives only for his people and has vowed never to take a wife, believing that a leader should make his people his priority, his family, his children. Yet he loves Dido unrequitedly, he helps her build Carthage, and he protects the city from would-be pirates as he guards the elephants from ivory hunters. Dido’s willingness to marry Aeneas and her joyous love in Aeneas’s arms offend Iarbas, who threatens to destroy Carthage—only Dido’s promise to kill herself and have her body buried in Iarbas’s elephant graveyard stops the elephant king from killing the Trojans and razing the city. Aeneas and the Trojans, heartbroken, flee Africa at Dido’s request. From the decks of their ships they watch Dido’s pyre burning.

Among this rather straightforward romantic conflict are two key subplots that extend the novels’ themes of love, gentleness, devotion, and leadership in important ways. The first involves Dido’s mother, the Nereid Electra, who manipulates most of these events: she encourages Iarbas to befriend and fall in love with Dido, she plots to kill Ascanius so that Aeneas will depart Carthage and leave Dido to rule as a true queen uncompromised by the presence of a gods-loved man who might usurp her importance, and finally she tricks Iarbas into discovering Aeneas and Dido making love in an orange grove, which prompts Iarbas’s to threaten Carthage. Electra, in the end, is killed by Aeneas when she reveals to him that Dido traded her life for his. She represents the seeming inability of those who live nearly immortal lives to comprehend the power of love. Across many of his novels, Swann revisits the idea that a brief love, no matter how short-lived, can be as powerful as a love that lasts a lifetime. And toward the end of his life, as he was increasingly sick and facing his own obvious mortality, Swann’s stories repeatedly valorized brief, deep, world-changing loves that mark the survivor (someone always has to die) forever.

The second subplot involves Dido’s homely sister Anna, who is presented as too masculine and too ugly to be loved, and so makes up for it with shrewdness and book-learning, and Aeneas’s closest friend, “faithful” Achates, whom Swann writes as a being unrequitedly in love with Aeneas. Swann explores Achates’s homosexuality in several touching scenes with Dido, who avers his love (the romantic, sexual love between men) as equal to that between a man and woman in the eyes of the Goddess (Astarte, Ishtar, Aphrodite—another theme of Swann’s: all goddesses are instances of the Goddess, who represents love itself), and affirms that queer love is a normal part of all ancient cultures. As I’ve shown in plenty of previous essays on Swann, his novels often celebrated queerness, defended the historicity of homosexual and bisexual relationships, and explored them as romantic and sexual ideals, nowhere as prominently as in How Are the Mighty Fallen. Still, Swann awkwardly and very unfortunately undercuts the wonderful scenes between Achates and Dido with his misogynistic handling of Anna, who is so ugly that, in the end, only Achates is willing to sleep with her (and even then, he complains to Dido that it’s as though Anna raped him!).

Queens Walk in the Dusk would be a contender for Swann’s best novel had it not been (understandably) rushed. The climax of the novel happens so suddenly that it is almost anticlimactic; the novel is easily 20–30 pages too short, as Aeneas and Dido’s separation is written more like an outline, lacking the emotion and heft of the rest of the novel. Even the revelation of Dido’s death comes across merely as a fact, with hardly a response from Aeneas, Ascanius, or Achates, who have all come to love Dido in different ways. I have no doubt that the awkwardly rushed ending was due to Swann’s sickness and death, a death that apparently came much sooner than expected, since Page notes that as late as April 1976, a month before his death, Swann had written to say that the prognosis was beginning to look positive. Perhaps the novel was even finished, however briefly, by someone else, because the ending certainly doesn’t feel like Swann’s. It lacks his vision, his emotion, his character.

But for what the novel does accomplish, for its exploration of an unconquerable but time-bound, tragic love between Aeneas and Dido, and for its seamless interweaving of Swann’s prehuman fantasies, Roman and Phoenician myth, and a jealous, telepathic elephant king, without making the whole absurd, Queens Walk in the Dusk has to be remembered as one of Swann’s finest accomplishments. The novel is a testament to Swann’s vision of emotional, gentle, queer fantasies that reimagine and challenge the cultural lessons—especially about masculinity, heroism, and community—that have been wrung from the myths that form the foundation of “the West.”

I want to end this piece with the final words from Swann’s final author’s note (since Cry Silver Bells, his last-published novel, did not include one), which read in retrospect as bittersweet and offer a final thesis on his work:

In The Aeneid, a poem which he wrote to please the Emperor Augustus, Vergil borrowed liberally from Greek and Carthaginian sources—both mythical and historical—and distorted them to glorify Rome. In certain instances I have followed Vergil; more often, however, though using some of his characters—Dido, Aeneas (whom he found in Homer), Ascanius—I have motivated them to tell a different and much less ambitious story. I do not believe in the right to distort history. I do believe in the right to reinterpret myth. Thus my interpretation, a myth and not a history.

An author should never explain his work. The work is the explanation and hopefully justification.

Reader, justify me and be blessed.

Revile me and choose another book and fear no curses from one who knows his limitations.

Muse, give my readers a nudge.

I need a little (a lot of?) help. (125)

Reader, take this as a nudge. Justify Swann, read his work, and you will be blessed indeed.

To get notifications about new essays like this one sent directly to your inbox, consider subscribing to Genre Fantasies for free:

Thanks for this whole series! I admit I have long dismissed Swann’s late novels. Most of them seemed a bit rushed to me — and I felt like Lady of the Bees and The Tournament of Thorns were each ill-advised expansions/additions of his two truly great shorter stories (“Where is the Bird of Fire?” and “The Manor of Roses”.) But you convince me they deserve another look.

I have read almost his entire corpus — but not Queens Walk in the Dusk! (for obvious reasons having to do with the distribution (or not) of the Heritage Press edition.) Jones was one of my favorite artists in that time — the book may well be worth it for the illustrations alone!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Rich! I’d say Lady of the Bees is, to me, his finest or maybe second finest novel (with Wolfwinter the great contender here), but this one is certainly excellent if underbaked at the end for understandable reasons. Shouldn’t be too hard to find on eBay. I don’t think I spent more than $25 and the illustrations certainly make it worth the while!

LikeLike