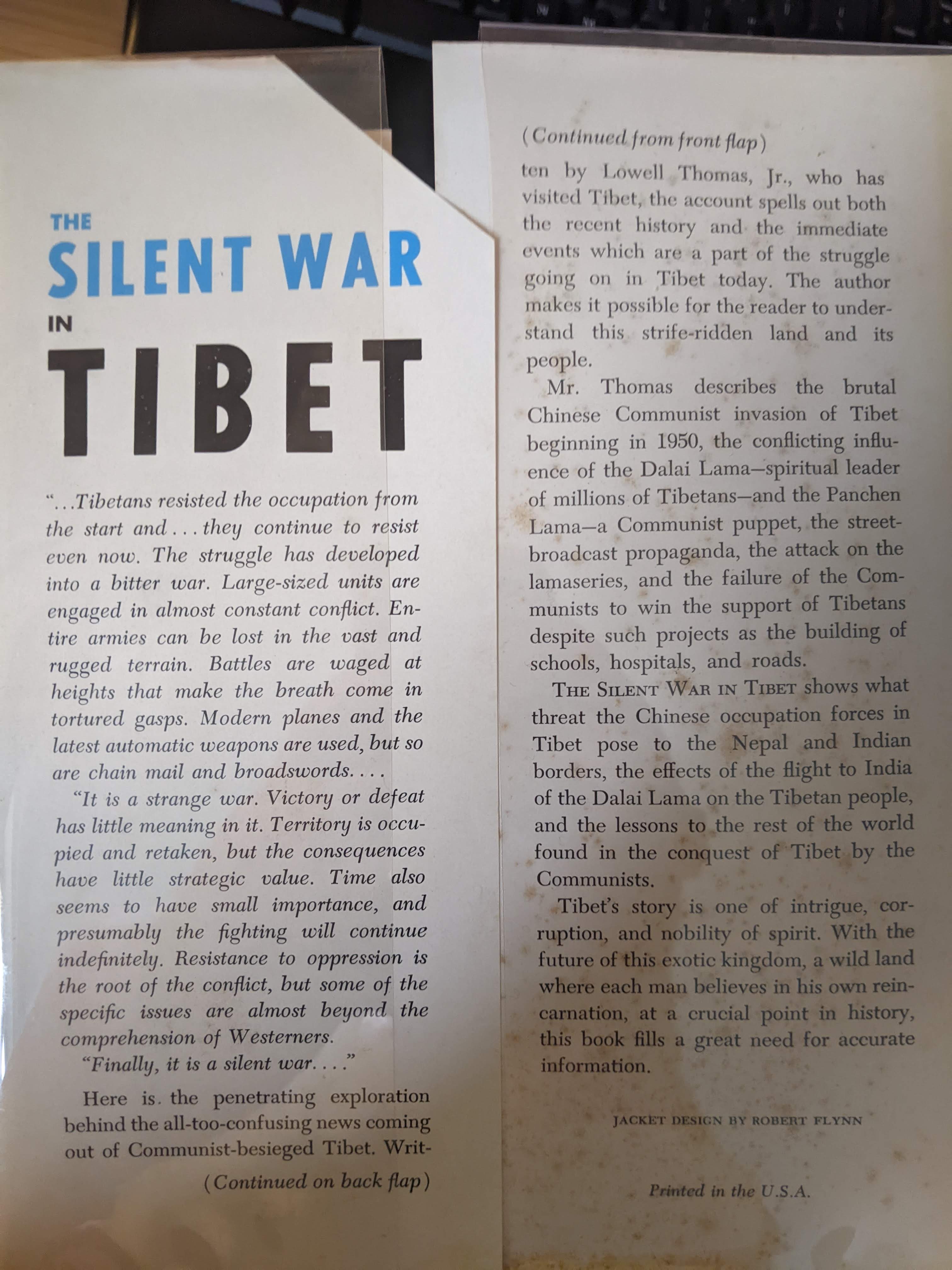

The Silent War in Tibet

Lowell Thomas, Jr.

Doubleday & Company, 1959

Before the mid-twentieth century, Tibet was little known in the West. It was familiar mainly to (1) scholars of Buddhism and the history of religion; (2) the occasional missionary; (3) mystics, spiritualists, and theosophists; and (4) military and political officials from Britain, Russia, who were waging the so-called “Great Game” for Central Asia, and later France and, by World War II, the US. Even among these Westerners, Tibet was known largely through second-hand information—with rare exceptions, like Rinchen Lhamo’s We Tibetans (1926)—since few foreigners had been allowed to travel in/to Tibet, let alone to visit the holy capital of Lhasa or gain audience with Tibet’s political and religious ruler, the Dalai Lama. For the most part, Tibet was a strawman in philosophers’, theologians’, and historians’ arguments about the nature of religious and cultural change—arguments made with little to know first-hand experience of Tibet, as detailed exhaustively in Donald S. Lopez, Jr.’s Prisoners of Shangri-La: Tibetan Buddhism and the West (1998).

Drips of information were fed to the West through manuscripts bought (or looted) in Nepal and India and through the writings of adventurers like the Frenchwoman Alexandra David-Neel, who in 1924 was the first (known) European woman to visit Lhasa (incognito and illegally, but after 12 years of preparation learning Tibetan and Buddhist practices and traveling elsewhere in Tibet). The Orientalist mystery of Tibet—as an untouched, unexplored, unconquered land of awe-inspiringly heavenly terrain ruled by acolytes of an exotic, aesthetically vibrant, and little-understood religion—was further teased in novels like James Hilton’s bestselling 1932 Lost Horizon and its 1937 Hollywood adaptation.

Encountering Cold War Tibet

Then, in the 1950s, Tibet found itself unwittingly and unwillingly at the center of the Cold War when, in the course of a decade, the Chinese under Mao invaded, occupied, and incorporated Tibet into the nascent People’s Republic while Tibet’s autochthonous government was forced, ultimately, into exile. Westerners, especially Americans, were outraged by godless Red China’s conquest of this humble religious kingdom and they wanted to know more. Tibet offered the perfect example of all that the West feared about Communism’s spread in the early days of the Cold War. And the Western hunger for information about Tibet created a cottage industry of popular depictions, fictional and factual, that was fed by films and best-selling hardcover and mass market books that sought to capture both the mythic, Shangri-La-esque qualities of Tibet in the earlier Western imaginary and to put the Buddhist kingdom into contemporary political perspective. This wave of books included those by both Westerners who could serve as guides to Tibet for the uninitiated and by Tibetans themselves, including “Lobsang Rampa” (who turned out to be a British guy from Devon).

Perhaps the most well-known of the Americans who introduced Tibet to the world, through both film and non-fiction based on personal experiences in, and familiarity with the major figures in recent Tibetan history, were Lowell Thomas and son Lowell Thomas, Jr. The former was a Renaissance man: adventurer, journalist, radio personality, filmmaker, businessman, world traveler, pilot, mountaineer—a truly self-made mover-and-shaker among America’s political and cultural elite with more than 50 books to his name. In short, the kind of man who was likely to be admired by sincere readers of Adventure magazine, National Geographic, and The New York Times alike. Born in 1892, Thomas made a name for himself photographing, filming, and chronicling the exploits of T.E. Lawrence in the Middle East during and after WWI. He parlayed this success into a career traveling—which became the basis for his extensive travel writing and non-fiction adventure-focused histories of places then little known to Americans—and reporting on world affairs, even flying a plane over the German capital in the midst of the Battle of Berlin, reporting the Soviet campaign live on the radio. In addition to his voluminous writing, he was a magazine editor, radio newscaster, and filmmaker. He made films, became a promoter of the Cinerama format in the 1950s, and helped found the company that became the American Broadcasting Company (ABC). Together with this son, he traveled the Himalayas and to Tibet in the 1940s, supposedly at the invitation of the Dalai Lama himself (15 at the time); this trip became the basis for their co-authored book Out of this World: Across the Himalayas to Tibet (1951) and an episode of his TV show High Adventure with Lowell Thomas (“Tibet,” 1958).

The Thomases’ Out of this World was a typical travelogue introducing the Himalayas as the boundary between south, central, and east Asia; as a site of recent adventure in the first half of the 1900s by mountaineers from Europe; and as the home to tiny, mysterious mountain kingdoms like Tibet. A great deal of time is spent focusing on Tibetan culture and history, insofar as the Thomases understood it, and explanations are given of the Buddha and Buddhism. Much of the relevant information from this book is recapped in the Tibet episode of High Adventure, which begins with Lowell Thomas in his pressed American business suit, sitting in front of lamas in an Indian Buddhist monastery explaining this “strange land,” decrying the invasion of Communists who deny god, before cutting to nearly an hour of older footage captured by Thomas, Jr. in 1949 during their 400-day expedition to Lhasa.

It’s a fascinating, sometimes funny documentary of their trip and showcases all of their and their audience’s enthusiasm for knowledge of the postwar world—and the Orientalism of that enthusiasm. The documentary also reveals that (at least in their interpretation) the Thomases were invited to Lhasa by the Dalai Lama in order to document Tibet and to carry a message to the West of the impending communist Chinese invasion, since, as Thomas, Sr. puts it, “they’ve hear the [Western world] opposes communism, the Red Tide that they themselves so greatly fear.” The impending invasion (already accomplished by the time of the documentary’s release) is described as China’s strategic bid for greater control of Asia.

The Silent War in Tibet

In 1959, Thomas, Jr. followed up his and his father’s book with The Silent War in Tibet—a more hard-hitting and politically poignant work of journalism that addressed the monumental social and political changes in Tibet since the publication of Out of this World. It’s curious that the Thomases didn’t reunite to co-author this book, but in general Thomas, Sr.’s writing veered toward the “non-political” with the exception of general condemnations of communism. Moreover, as High Adventure makes clear, Thomas, Jr. seems to have become more intimately familiar with Tibet, its cultural ways, and the folks met along the way than Thomas, Sr.

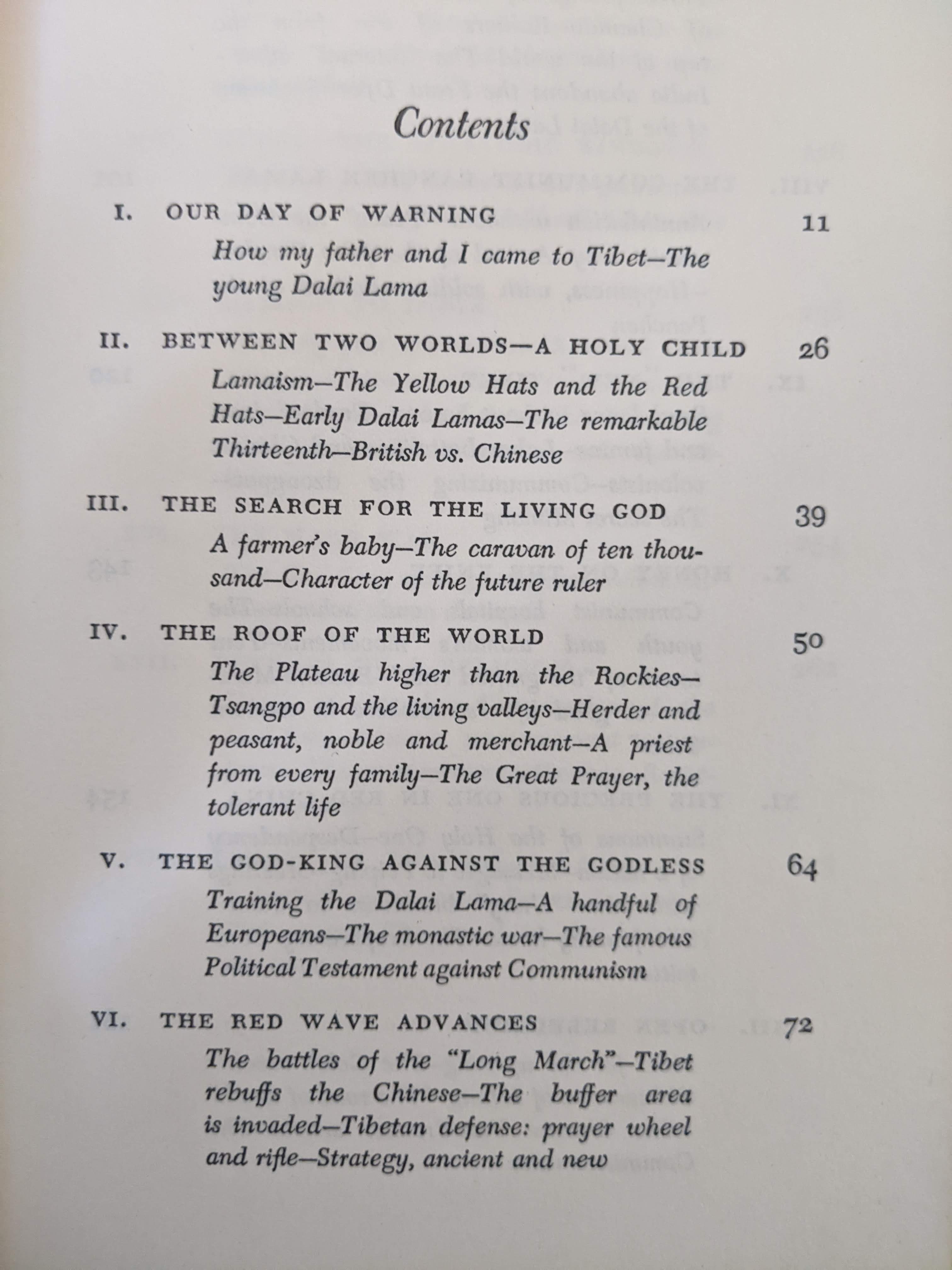

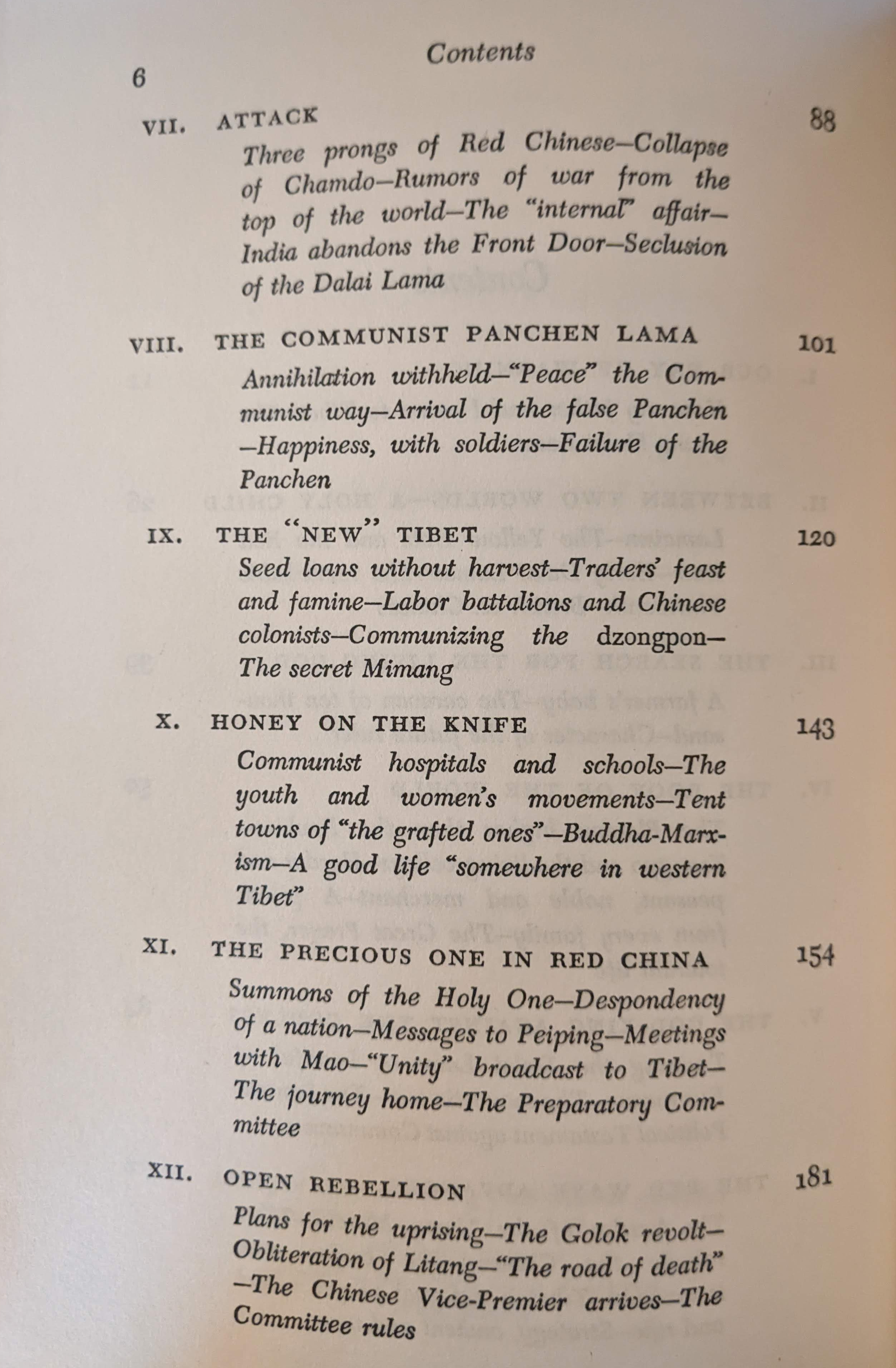

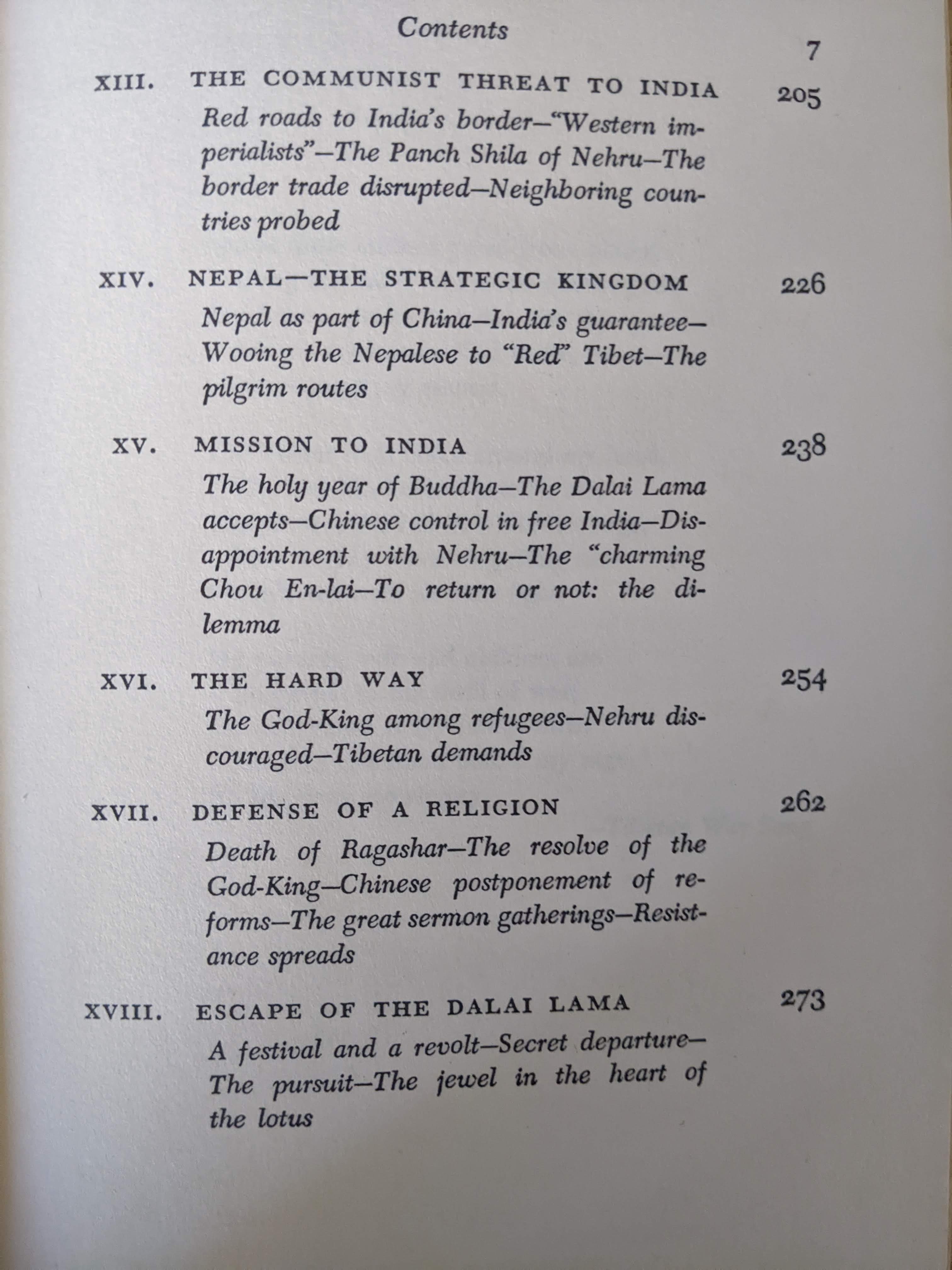

Whatever the reason for Thomas, Jr. striking out on his own to write The Silent War in Tibet, the book is an important document of midcentury American efforts to know the shape of the world in this new Cold War, offering a journalistic account of a major battleground in the real and ideological war between east and west, communism and capitalism, a world heating up in the wake of the Korean War, the rise of China as an independent communist power, and the implementation of domino theory in the wake of socialist and communist revolutions the world over. At just under 300 pages, the book offers a geographic study the Himalayas and Tibet; a social and political history of Tibet and its complex relationship to China that is at once theological and political; a history of the internal politics of Tibetan Buddhist orders, lamas, and monasteries; and most importantly a nearly day-by-day account of the Chinese invasion and occupation of Tibet, Tibetans’ and the Dalai Lama’s resistance, and the ultimate exile of the Dalai Lama.

Thomas, Jr. has a keen eye for the complex geopolitical machinations of the Cold War order, addressing the roles of Chinese, Tibetan, Indian, Nepalese, and Western officials in the nearly decade-long struggle of Tibetans against Chinese occupation and ultimate incorporation into the People’s Republic. Thomas, Jr. rarely describes the sources of his information, simply relays details as fact, but he gives occasional glimpses into his network of relations that suggest much of his information comes from interviews gathered from Tibetan refugees in the Indian Himalayan borderlands with Tibet—that and likely articles from the Indian and Tibetan expat press, which captured the internal details of Tibet much more so than any Western source. The Silent War in Tibet is unclear in its source material but thorough in its detail, betraying Thomas, Jr.’s background as a travel writer more so than a professional journalist, though I’m not familiar enough with journalists’ non-fiction at this time (late 1950s) to say whether a journalist would have similarly written so as to give primacy to the narrative (and the author’s telling of that story) over the sources of the narrative.

In The Silent War, Tibet’s recent history is told with the pressing excitement of a narrator who wants readers to understand the confluence of local, regional, and global geopolitical forces at work in this small, largely unknown nation that seems, to readers, just barely out of the Middle Ages—a religiously organized peasant society whose military, just prior to the Chinese invasion, is still using 19th century muskets. For Thomas, Jr. the story of Tibet’s struggle to retain independence is breaking news that captures the major issues at the heart of the global Cold War and representative of the political and human stakes of this new period of history readers are living through. Like the best of such journalism, Thomas tries to give a sense of the importance of his topic to the life of the reader, however truly improbable a midcentury American’s connection to Tibet might seem. To read The Silent War in Tibet, with its granular but lively detail of Tibetan society, of Chinese modernization programs, of underground resistance movements, of a mostly powerless Dalai Lama searching for the best—any—course of action to safeguard Tibetan autonomy, is to feel involved in the geopolitical question of Tibetan independence and Chinese occupation, much in the same way that news stories today make us feel part of the struggles of the Afghans, the Sudanese, the Palestinians, the Congolese—and to see our complicity in (or, perhaps, our allegiances to) the global system that has brought about the wars and tragedies journalists cover.

At the same time, Thomas, Jr. does have his political agendas and his book, knowingly or not, is enlisted in the larger project of the US empire’s conflict with communism. For anyone committed to America as an idea, and committed to the idea of the West’s technological and, likely, cultural superiority, Tibet offers a striking conundrum. Lopez wrestles with the history of that conundrum—that is, what Tibet represents to Western intellectuals and its implications for the social, theological, and political concepts through which they view the world—in Prisoners of Shangri-La, mentioned above. Tibet checks a number of boxes in the American imaginary of the Cold War world: a deeply religious kingdom, a non-Christian one but whose religion is often equated to having a Christian or at least Catholic structure (with a supreme deity [the then common interpretation of the Buddha], canonical texts and a scholastic tradition, monastic orders, and a divine relationship between god and ruler), an underdeveloped nation, a strategically important nation, a nation threatened by communism, and a nation resistant to communism. But it also has little value to the global community (especially in terms of trade) aside from its position, as the British long acknowledged, as a geographic buffer zone between east and south Asia.

Laying out the complexities of Tibetan-Chinese relations, Thomas, Jr. details the history of Tibet’s claim to sovereignty from China, a history that resonates especially clear in the increasingly decolonized world of the 1950s but which changes the tune away from racial or “merely” political (or even economic) arguments for decolonization and independence. Thomas, Jr. emphasizes the religious dimension of Tibetans’ claim to sovereignty, as though Tibet has a claim to a natural, spiritual right to be distinct from China, in a relationship whereby Tibet and China both benefit (Tibet materially, defensively; China, spiritually). In Thomas, Jr.’s history, Tibet is torn between two imperial powers, China and Britain, up until its annexation by communist China in the 1950s. In fact, while Lowell doesn’t seem to really condemn imperialism itself and the way either Britain or China sought to assert control in the region, he does condemn the fact that it’s communist China (with its anti-religious policies) doing the imperializing now.

No doubt the communist dimension of China’s annexation of Tibet—the first time in the Cold War that one of the major players fully took control of a country, and that it was a communist one to do so—played a huge role in the growth of interest in the 1950s and 1960s in the plight of Tibet, since it offered the opportunity for Westerners to decry the communist despoiling of an ancient, seemingly untouched, “medieval” society, the last vestige of an old world, of an exotic, peaceful Asian nation of peasants and monks, an innocent non-threat devoured by teeming Red masses. Tibet’s fate gave a clear example of the domino theory: if Tibet could fall, and so soon after a stalemate in Korea wherein the US failed to achieve victory over communism, then more nations in the region could fall too. (The West was already nervous about the non-aligned countries of Central and South Asia generally, having orchestrated a coup against the socialist leader Mosaddegh in Iran in 1953 and fearing the left-leaning politics of Nehru in India.) Tibet’s plight signaled to Americans exactly what they feared communism would do in a world where it wasn’t just the USSR, but now also China and potentially other nations who called themselves non-aligned but had left-leaning leaders (Iran, India, Indonesia, Brazil, newly independent African nations, etc.) to be concerned about.

Beyond this anti-communist framing of the conflict, Thomas, Jr. also intervenes in some of the ideological battles the Tibetans are waging. For example, the recognition of incarnations of the Panchen Lama became a major issue in the Chinese’s attempt to gain a foothold in Tibet and maintain control and legitimacy. When the 9th Panchen Lama died in 1937, more than a decade before the PRC’s invasion of Tibet and in the midst of the Chinese Civil War, the Chinese Communist Party threw their weight behind the recognition of Gonpo Tseten as Panchen Lama, while the Dalai Lama and the monks in Lhasa preferred another candidate they identified as the “true incarnation.” Thomas, Jr. details how Gonpo Tseten was trained by the Chinese as a communist and inserted into Tibet as a vanguard element to aid the eventual communist takeover. Thomas, Jr. refers to Tseten only as “Mao’s Panchen” throughout the book. Mao’s Panchen went on to have a rather tumultuous relationship with the communist party and its not clear that he played a major role in securing an ideological victory for communism; he was also not always a willing participant in communist propaganda, being imprisoned in the 1960s and forced to undergo struggle sessions after he criticized the atrocities of the communist regime in Tibet. To this day, the recognition of the Panchen Lama (that is, Tseten’s successor) is a major political issue in Chinese-occupied Tibet and for the Tibetan government-in-exile.

Thomas, Jr.’s The Silent War in Tibet gave voice in late-1950s America to a conflict that expressed the West’s worst fears about communism, that exemplified the geopolitical issues up America was facing as it entered the 1960s and communism showed no signs of flagging (indeed, Tibet was the focal point a major crisis just three years later, as detailed in Bruce Riedel’s JFK’s Forgotten Crisis), and that offered a relatively unproblematic (from the perspective of Western imperialism) case for the sovereignty and independence of the small nations of the world—the “little guys” who could really use some good ole American uplift (i.e. military aid and global development attention). For the historian, Thomas, Jr.’s book is a not-unbiased but nonetheless illuminating account of the daily struggles of Tibetans and, most importantly, of the efforts and local responses thereto of communist leaders to bring development, propagandize, maintain control in a region—like Xinjiang—that the People’s Republic had to work to, essentially, colonize and where major atrocities and human rights violations were doled out in the name of “liberating” Tibet from Western imperialism and the rule of monastic orders.

The Silent War in Tibet is a deeply personal account of a land that is not the author’s, of a political struggle that captured Americans’ attention and which made the Dalai Lama a household name. It’s also a work that is deeply touched by postwar American anti-communism, dedicated to American idea of freedom of religion, disillusioned by the West’s failure to act in Tibet’s interest, and realistic about the future of a nation unlikely to regain independence given to the geopolitical stalemate of the Cold War in the wake of the Korean War. It’s a book well worth reading for anyone interested in the Chinese occupation and annexation of Tibet—a political control that has continued into the present, became Hollywood and hippies’ cause célèbre in the 1990s and early 2000s, and has led to increasing political unrest among Tibetan monks and dissidents, and the expected crackdown by Chinese officials. For the briefest and most accessible (though not exactly scholarly) overview of Tibet’s situation in the past quarter decade, spend 20 minutes with John Oliver’s segment on the Dalai Lama.

Lowell Thomas, Jr.’s The Silent War in Tibet is also a great resource for scholars of postwar American imaginaries of Asia. I admit to being a little obsessed with Cold War efforts by Americans to create knowledge about the new world order by bringing accounts of the non-Western world to the broader readerly public, and The Silent War in Tibet is a perfect match for the obsession, for its author embraces the Orientalism of old, rejects the notion that Tibetans are a simple people undeserving of sovereignty, offers apologia for Western imperialism, condemns communist imperialism, and is deeply committed to the national sovereignty of a people who aren’t his own. It’s a mess of contradictions that is so perfectly postwar American.

Postscript

For those interested in details of the contents of this book, which is easily available from secondhand sellers online but which lacks much information about it online, I thought it might be helpful for me to provide some information, including the book’s cover copy and its detailed table of contents. (Sorry, I’ve only included images because frankly I don’t want to type all that stuff out.) There is also a very detailed map in the endpaper, but I can’t get a good photo. If you have questions about the volume for research purposes, I’m happy to try to answer them.