Out There by Adrien Stoutenburg. 1971. Laurel-Leaf Library / Dell, 1972.

Table of Contents

Stoutenburg and Dell’s Laurel-Leaf Library

Reading Out There

A Novel of Ecological Nightmare—and Capitalist Exploitation

One thing that’s important about the work of digging into the “great unread” of postwar sff—especially the stuff that’s out of print but still easily available via used sellers at a fraction the cost of new, in print books—is that it helps us to better understand that actual shape of the literary history we write about. Especially when that literary history concerns how authors used a popular genre and its affordances to respond to pressing social and political crises of their day. This recovery work can move us beyond the big names and big books that have garnered enough attention to remain in print or get new printings and bring fresh voices to old conversations.

Such is the case with Adrien Soutenburg’s 1971 novel Out There, a now largely forgotten and long out of print novel. It’s a story that extrapolates the environmental crises of the 1960s–1970s into the 2010s, but does so in ways almost mundane in order to make clear just how high the impact of unchecked ecological destruction could be on everyday life. I first heard of Out There on the ForFemFan (Forgotten Female Fantasy) blog, which reviewed the novel in May 2021. Though ForFemFan did not exactly like the novel (and I largely agree with their assessment of its qualities as a novel), I couldn’t ignore that this was an ecological (post-)post-apocalypse novel from the early 1970s that I had never seen referenced in the now quite voluminous academic criticism on ecological sf. I was also all the more enticed by the author being a woman I had never heard of. And, most importantly, I fell in love with the raccoon on the cover.

Out There is not exactly a thrilling novel, nor a particularly great one, nor one with a raccoon (ForFemFan did warn me!), but instead a quiet exploration of a world that environmental activists have been working to avoid for the past 60 years and which seems ever just over the horizon, only the shape of that future has continued to morph as the geopolitical shape of the anthropocene has mutated in the half-century since Stoutenburg’s novel. Out There sheds a dim, harsh light on the interlaced dangers of capitalism, environmental catastrophe, scientific negligence, and what happens when we turn our back on restoring the earth and put our political and economic energies toward the idea of space colonization as the salvation of humanity. No great literary achievement, and at times narratively flat, Out There nonetheless stands beside Ernst Callenbach’s later Ecotopia (1975) as an interesting, important ecological sf novel that was in conversation with the early environmental movement.

Stoutenburg and Dell’s Laurel-Leaf Library

One reason Out There might have been overlooked by sff scholars, aside from its having never been reprinted, is that it is and was marketed as the early-1970s equivalent of YA fiction by an author who wrote mostly poetry and non-sff-y children’s and adult fiction. In addition to five poetry collections and six novels for young adults, Stoutenburg (1916–1982) also wrote collections of stories, poetry, and novels for much younger children, including a number of folktale collections, as well as fifteen nonfiction books on nature, history, and culture. Among these latter are several relevant to Out There: Stoutenburg wrote two books about endangered and “rare” animals in the United States (A Vanishing Thunder: Extinct and Threatened American Birds in 1967 and Animals at Bay: Rare and Rescued American Wildlife in 1968) and a biography of Walt Whitman entitled Listen, America (1968). In total, Stoutenburg wrote 48 books between 1943 and 1979 (with one poetry collection published posthumously in 1986).

Out There was Stoutenburg’s final novel, published in 1971 by Viking Press and issued the following year in mass market paperback by Dell’s Laurel-Leaf Library imprint, which repackaged classics and recent hardcover releases for a hip youth market. The interior copy of the Dell edition explains that:

The Laurel-Leaf Library brings together under a single imprint outstanding works of fiction and nonfiction particularly suitable for young readers, both in and out of the classroom. This series is under the editorship of M. Jerry Weiss, Distinguished Professor of Communications, Jersey City State College, and Charles F. Reasoner, Professor of Elementary Education, New York University. (n.p.)

Launched in the early 1960s and branded with the academic seriousness of education scholars behind it, Laurel-Leaf Library at the same time courted a youth audience by packaging books both in the then relatively new and extremely popular mass market paperback format and by papering its covers in the style of the appropriate genre. The imprint regularly published mystery, horror, and science fiction (and in the 1980s operated a separate fantasy imprint), including by authors such as Isaac Asimov, Robert Silverberg, Robert Heinlein, and Madeleine L’Engle, as well as classics by Edgar Allan Poe, Oscar Wilde, and Mary Shelley.

In re-releasing Stoutenburg’s Out There, Dell used the tagline “The first major novel of ecological nightmare” on the front cover, and offered the following back cover copy, with the first two instances of the word “America” in large, bold red letters:

America:

The Near Future!America:

Danger—Contamination Zone!Sometime in the early part of the twenty-first century, cities lay sterile under steel and plastic domes. It is the only world a teenager can know. Earlier generations violated every rule of ecology and laid plunder to their country.

Somewhere, though, out there was another world. There might be animals. There might be other life. There might be death.

This dramatic copy is accompanied by a short summary of the six major characters and the predicament they face “find[ing] a way out into the brave old world OUT THERE!” Dell also gave Stoutenburg space in the interior copy to explain here reasoning behind the book:

Out There was an almost inevitable result of my long interest in, and concern for, threatened wildlife and landscape. With the steady destruction of various wild species, it seems all too probable that within thirty or even fewer years the only “wild” animals will be those in the zoos. (n.p.)

All of this is wonderful and helpful context for understanding that, like Stephen Kahn reviewing it in the New York Times, Out There was considered by the institutions promoting and responding to it as addressing a pressing political concern that might very well result in the world of the novel tomorrow.

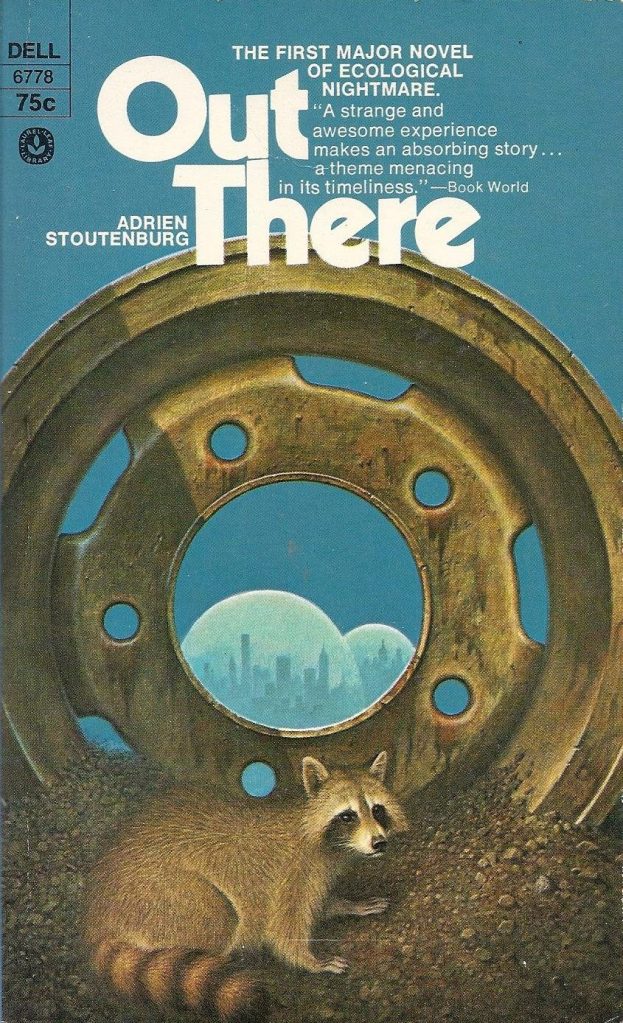

The sentiment is mirrored in Dell’s cover, painted by an unnamed/unidentified artist, which features a raccoon poised beneath a giant, rusted hubcap, partly buried in the gravel and dirt (note: there are at least three other covers, including two from 1971 by Viking and another from 1979 by Penguin Random House; I haven’t included them here because high-quality images are hard to find). The hubcap stands upright and through its center we glimpse domed cities far in the distance. The pristine, steel-and-plastic cities of the novel’s future are framed through the refuse of the past; this world of garbage in the foreground represents the past choices that pushed people into the domed cities, and the raccoon serves as a reminder of what has been lost—or what people of the cities think has gone extinct: all the creatures that made the world a thriving ecosystem, despite our piles and piles are trash.

The cover, the description, the hand-wringing about the future the novel portends—it’s all classic science-fictional prognostication demonstrating how sf is always about the moment of its creation. But how does it hold up, as a novel, and what insights does it offer us as an sf novel, supposedly the “first major novel of ecological nightmare”?

Reading Out There

The narrative of Out There is very simple, but weighted throughout with an attempt to dig into both the personal struggles of its characters and the emotional impact of a world that has transformed even the most mundane wild animals of everyday American life—squirrels, deer, raccoons, sparrows—into exotic memories of the past. The novel tells the story of the Nature Squad, a group of teenagers and one child, and their mentor and the child’s foster mother, eccentric Aunt “Zeb” (Zebrina), who take a trip into the wilderness, where they hope to discover that maybe, just maybe, nature has recovered enough from the environmental degradations of the twentieth century that an animal or two will have survived. For in this futuristic 2010s, the only living animals are pets and zoo animals kept in and around the domed cities where most of the human population now lives. The rest of the animals are believed to have died from pollution, pesticides, and perhaps even nuclear weapons or waste. Rather than restoring the environment, governments (it’s not clear if the US, all countries, a world government, etc.) are focused on getting into space: building up the moon and Mars as humanity’s new home, with the domed cities as a temporary stop-gap until space is ready for our exodus to the stars. There is no doubt that Stoutenburg’s Out There is an extrapolation of the future conditions warned against in Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962), an exemplification of what the anthropocene could lead to.

The novel is highly didactic and narratively structured to ensure something like a learning experience for its young adult audience. The Nature Squad members represent a range of character types—introspective Lester, obsessed with Indian philosophy, Nietzsche, and St. Francis of Assisi (because his dad is a macho space marine); strong Patrick, who just wants to lead everyone and do it well (because he’s poor); smart Sylvie, who is insecure and desperate for attention (because her parents are famous musicians); shy Fay, who is insecure (because she’s poor and fat); and eight-year-old Knobs, who fears abandonment (because she is an abuse survivor)—whose strengths and insecurities complement one another and allow young readers a broad range of identifiable entry points into the narrative. They are mentored by the whip-smart Zeb, likely in her late 50s/early 60s (which would make her a child in the 1970s). Zeb’s (dead) husband was a big game hunter who joyed in hunting the last members of various wild species; almost as if to make up for his crimes against nature, Zeb spends her time mentoring children to love the earth by taking them on hikes and teaching them biology, geology, and ecology. And she’s been doing it for a long time, as evidenced by her neighbor, an adult veterinarian, Steve, having been a former Nature Squad member. As ForFemFan notes in her review, Zeb is essentially Ms. Frizzle two decades before The Magic School Bus debuted. But Zeb’s not perfect, she gets frustrated from time to time, and her object lessons don’t always work out the way she’d like. The characterological frame of the novel provides an effective window into the world Stoutenburg has imagined. The teenagers in particular serve as exemplars of the kind of person readers might be: people whose curiosity for and love of the natural world might help avert Stoutenburg’s future.

Out There takes place in the 2010s somewhere in and around the Sierra Nevada mountain range, likely near Las Vegas. The narrative is a bit vague about the specifics, referring to the nearby major city only as New City—one of the high-tech, dome-covered cities that protect humans from the contaminated environment. Importantly, New City is home only to the rich; the poor live outside the dome, but commute in for school and work; much of the area immediately around the city is safe for human habitation, but everyone fears to travel too far from the city, lest they risk exposure to deadly toxins, chemicals, and pesticides that have killed off all the wild things. The story opens as the Nature Squad members, sequestered in their makeshift clubhouse in the attic of Zeb’s house outside New City, discuss a serious proposition they want to put to Zeb: an expedition into the wilderness, further than they’ve ever been, to find wild animals that might still be alive. Zeb thinks it’s a long shot but doesn’t want to dampen their spirits, and so agrees, imagining that after a few days of hiking and finding nothing, the Squad will agree to return home. She leaves her pets (dogs, cats, and a caged bird) in the care of Steve, whose adulthood has disillusioned him of his youthful Nature Squad lessons to instead think of nature as a lost cause (he is now training to be a vet in space). The group takes off in a wonderfully 1970s station wagon, makes it to the mountains, and hikes off into the wilderness.

And they find animals: first in a trickle (a wild dog here, a mosquito there) and then in increasing abundance once they’re days into the wilderness—a ground squirrel, a doe and her fawns, a moth, a flicker, a crow, a chipmunk, a bat, some trout, and more. And, of course, a few things go wrong: Lester breaks the compass during an encounter with a starving wild dog, Zeb breaks her glasses and so can’t guide the group, Fay gets a painful blister, and they run into a loner named Josh, who is barely surviving out in the wild by hunting and fishing. Josh is about as gun-totingly confrontational as you’d expect (Stoutenburg’s vision of a Goldwater ’64 voter?) and tries to get the Squad lost with misdirection. Then he shows up just as the Squad sees a doe and her fawns; Zeb intervenes, placing herself between the gun and the deer, and when Josh threatens to shoot Zeb, Lester uses Zeb’s old rifle to snipe Josh’s ankle. It’s a surprisingly stark and violent moment in an otherwise quite placid novel. Lester’s father is a space marine who trained his son to use weapons, but Lester prefers a life of introspection and regularly recites lines from the Baghavad Gita or teachings from a yogi’s book he’s been reading, while imagining himself as the new St. Francis of Assisi, protector of and communer with animals. Hurting another living being tears Lester up inside. And things get a little worse: just after incapacitating Josh, a military aircraft out on maneuvers zooms by and its wake blows the Squad’s gear away, leaving them virtually helpless in the wilderness with one adult unable to see and another slowly dying of blood poisoning from a bullet in his ankle.

But despite these setbacks, Zeb convinces Josh to let her and the Squad take care of him at his hidey-hole in the wilderness—which turns out to be a massive, abandoned mountain vacation lodge that is miraculously in working condition, still has some stocked canned goods, and sits next to a lake abundant with trout. The Squad passes a few days happily at the lodge while Lester broods over hurting Josh, Patrick takes up leadership of the group, Knobs reckons with her past trauma and gets a glimpse of a beautiful white (wild-ish) horse (which she thinks is a pegasus), Sylvie learns that she doesn’t need attention from her parents to feel valuable, and Fay—well, she loses weight from the exercise and under-eating and so is really, really happy. After a few days of personal growth and relaxation, the Squad is rescued when Steve arrives in a fancy super-helicopter owned by entrepreneur Ed Collier. And one of the first things Steve says is how nice and skinny Fay looks. (This novel really hates fat people.)

But the Squad’s experience of renewed nature, a world they thought was long gone, and their rescue by Ed Collier are overshadowed by Ed’s realization that wild animals still live in the mountains and that, contrary to scientists’ statements and his helicopters’ instruments (which have been set by manufacturers to record dangerous levels of contamination outside of population areas, even when no contamination is present), the air and water here are perfectly safe. Ed made his money in the late-twentieth century running a commercial fishing company and is looking to expand with new ventures. The novel ends with the suggestion that Ed will buy the mountain lodge property and turn it into an eco-tourist destination. Zeb hopes he’ll forget about it, a suggestion perhaps added by Stoutenburg to tempter the otherwise incredibly bleak conclusion for her young audience: so long as capital thrives, nature will always be exploited.

A Novel of Ecological Nightmare—and Capitalist Exploitation

Out There is not an incredible novel; it’s not even a particularly good one. But it is an interesting one both for its subject matter and its timing. Stoutenburg’s interest in preserving the environment, and especially the lives of animals, and arguing her position through the lens of science fiction, make this book a worthwhile study for any scholar of the genre who engages with environmental themes. The historical positionality of the novel is fascinating and speaks to distinctly late 1960s/early 1970s concerns. Indeed, the novel hardly feels like it is set in the future at all. Aside from the domed cities and references to mining on the moon, trips to Mars, a military corps of space marines, and a few futuristic technologies, like Ed’s super-helicopter or a watch that sounds suspiciously similar to an Apple Watch (though Zeb doesn’t own one), the world of Out There is very much that of the early 1970s. The concerns of the Nature Squad members, their personal problems, all seem taken directly from a 1970s melodrama and readily reflects the disillusionment many felt about life in the U.S. in the 1970s, a transformation in cultural attitude that turned the utopian world of the kids in The Brady Bunch (1969–1974) into that of the kids from Fame (1980) by decade’s end. While the novel’s melodrama is nothing unique for the period, its clear ecological vision is.

Out There harshly critiques unregulated capitalist and military exploitation of the environment, making clear that things “as they are” in 1971 portend a bleak future. And Stoutenburg is clear that that future is already edging into view. Zeb laments, for example, the extinction of the California condor some decades before the novel takes place. There’s no real reason, from the vantage point of the storyworld, to call out this particular species since nearly every wild animal, from squirrels to deer to sparrows (hell, even mosquitoes), are thought to be extinct in Out There’s 2010s. But in our 1971, condors had been listed as endangered by the federal government four years earlier and were given state protections the same year Out There was lamenting their demise. Stoutenburg and everyone else knew, by 1967, that pesticides and especially lead poisoning of the environment were major factors in condors’ endangerment and by 1987 only 22 condors still lived. The future of Out There could even be glimpsed in advertisements, most famously in Keep America Beautiful’s 1970 “Crying Indian” PSA staring noted pretendian “Iron Eyes Cody,” which showed America as a fallen hellscape of cars, industrial pollution, and garbage. It’s the same landscape Stoutenburg describes as the Squad travels by station wagon to the Sierra Nevadas: garbage and the wreckage of industrial America everywhere. America was felt by many to already be a dystopian environment. Stoutenburg extrapolates this 1970s structure of feeling into a future that feels real, pressing, even “urgent” to readers of the era, leading New York Times critic Stephen Kahn to conclude that, though Out There is simple, obvious, and stereotypical in its storytelling, “a sympathetic novel about ecology, directed to the generation which must restore the environment, should be given the benefit of every doubt.”

While Stoutenburg was not otherwise an sf author, and while she puts very little energy into writing Out There as an sf novel, perhaps the most interesting part of her novel is a science fictional one. Throughout the novel, references are made to various ventures humans are making out to space. A clear timeline or explanation of the state of the world is never given in Out There. Josh briefly references his brother dying in a war “over in—” but never finishes the sentence (184). We don’t know if the U.S. still exists, if the Soviets are around, if there’s a world government, if city-states rule regional fiefdoms (like in Damon Knight’s A for Anything), and so on. We know functionally nothing about the future world except that overexploitation, failure to regulate, pesticides, the military, and perhaps war devasated the environment and people now live in and around domed cities. What is clear, though, is that nearly all economic and political activity is oriented toward getting humans into space. Already there is mining on the moon and “pressurized cities” ready for human habitation (188). Mars is next. Earth is old news, a condemned house with a few squatters waiting to leave.

But the same things that rendered earth (seemingly) uninhabitable are what make the human exodus to space possible: capitalist exploitation. The loner Josh lives in the wild because he wants to avoid that exploitation. Like Patrick and Fay, he is poor, and so was drafted in adulthood to join the Moon Mechanics corp. His background is explained in just four short paragraph (188–189), but they are likely the most politically exciting paragraphs of the novel. Josh, who is reminiscing to himself, describes things like a “Truant Task Force” which rounds up youth who try to evade school and government service. He describes being forced to study at the Southwest Regional Institute to learn how to become a Moon Mechanic, and explains that government “had talked a lot about educating him more, though as far as he could make out he wouldn’t be doing much different work than an unskilled worker did back in the old days” (188). Moon Mechanics are “[e]xpendable moon fodder” for the government and companies building up the “pressurived cities” for humans to escape to (188). Josh escapes that life of drudgery in the new command economy of space, which seemingly affords no choice, especially to those without the money to determine their career choices (like poor Patrick and Fay; unlike Sylvie, daughter of wealth musicians, or Lester, son of a space marine). And now that he’s injured, he fears being captured and redrafted.

This critique of capital and government’s entanglement, which expanded greatly in the 1970s and 1980s as deregulation came hand-in-glove with the growth of neoliberalism, is a brief but important glimpse at how Out There envisions the dangers of the future and how Stoutenburg ties together a critique of Big Government, capitalism, and environmental destruction. The politics of Out There, though, are quite muddled. Stoutenburg offers almost libertarian criticism of Big Government but utterly decries corporate power, industrialism, and capitalist fantasies of endless growth. She uses Josh to explain the double-bind of the poor in her novel’s future, but lambasts him as arrogant and selfish for killing animals. Through Zeb, she teaches very basic but rigorous scientific lessons about ecology, but takes every chance to lampoon doctors, veterinarians, and scientists as, essentially, short-sighted failures. Perhaps the latter is a critique of science’s capture by Big Government, but what exactly Stoutenburg is critiquing about either science’s interrelationship with government, or Big Government itself, is never clear. Out There’s politics, then, boil down to: don’t hurt the environment, don’t pollute, don’t kill animals—but also Big Government (who can enact regulation, say, through the newly established EPA in 1970) is bad. Seemingly incoherent, this actually seems like a pretty good summary of the ideological contradictions of the 1970s.

Stoutenburg’s Out There is a fascinating text of the environmentalist movement of the 1970s that uses sf to express the era’s struggle with the social, political, and economic complexities facing efforts to protect the environment. At the same time, Out There uses sf to to warn young readers of a future where the most mundane aspects of nature—the creatures we take so for granted that they don’t seem fascinating to us anymore—are distant memoires, and the glimpse of a grazing deer or the bite of a hungry mosquito are as science fictional to the Nature Squad as domed cities and space marines are to us.

To get notifications about new essays like this one sent directly to your inbox, consider subscribing to Genre Fantasies for free:

A lovely review Sean. This one has been on my radar for a long while but I have yet to pick up a copy. I should! I also adore delving into the SF esoteric…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah, thanks. Honestly this was like pulling teeth to write because it was, for the most part, quite a dull book to read. Maybe your experience will be better!

LikeLike