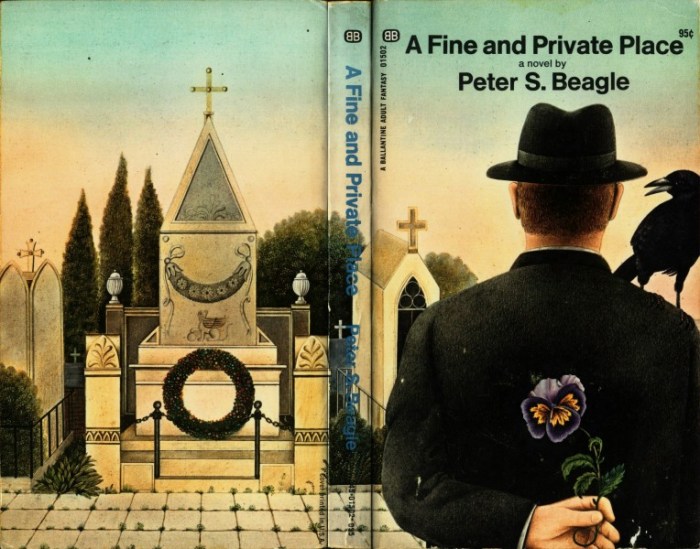

A Fine and Private Place by Peter S. Beagle. 1960. Ballantine Books, Feb. 1969. [My version: 1st printing, Feb. 1969]

This essay is part of Ballantine Adult Fantasy: A Reading Series.

I began this Ballantine Adult Fantasy reading series with an essay on Peter S. Beagle’s The Last Unicorn, which was republished by Ballantine Books, following its original hardcover release by Viking the previous year, as a mass market paperback in February 1969, shortly before the official launch of the series with Fletcher Pratt’s The Blue Star just two months later in May 1969. That very same February, Ballantine also released the first mass market paperback edition of Beagle’s first novel, A Fine and Private Place, originally published by Viking in 1960. Beagle was just 19 when he wrote the novel, but it was a minor literary hit. Read alongside The Last Unicorn, though, it’s a rather unexciting thing, like being offered a slice of plain but prettily decorated sheet cake straight from the grocery store when what you wanted was a slice of rich red velvet cake coated in cream cheese frosting from the local bakery. The only impressive thing about A Fine and Private Place is that it was written by a 19 year old and that its success led to the masterpiece that is The Last Unicorn. Yes, there are hints of that much more profound and accomplished novel in A Fine and Private Place, but on the whole it’s a rather dull if nonetheless pleasant affair.

Notably, while both Ballantine editions of Beagle’s novels predated the BAF series, both included the descriptor “A Ballantine Adult Fantasy” on the top left corner of the front cover. Here, Ballantine noted the genre categories of its books, like how they labelled another pre-BAF novel, David Lindsay’s A Voyage to Arcturus, as “A Ballantine Science Fiction Classic.” By February 1969, Ballantine already had the BAF series in the works, ready to publish in just two months, and they must have realized the value of beginning to preempt the series with this genre label. Only The Last Unicorn would go on to be reprinted with the series’s unicorn head logo; A Fine and Private Place was reprinted several times throughout the life of the BAF series but never (to my knowledge) with the series logo and was instead given the genre label “A Ballantine Book,” used for the publisher’s general fiction offerings. Both Beagle novels also sported covers painted by the Spanish surrealist Gervasio Gallardo, whose covers graced a significant number of BAF titles in the years to come.

It made good sense, ultimately, that A Fine and Private Place was not later reprinted under the BAF banner (even if Lin Carter considered it one of the “preface” novels). Though Ballantine would ultimately relent and publish later printings under Del Rey’s cockatrice logo for fantasy titles—probably to cross-promote this more obscure book with The Last Unicorn and encourage sales-by-proximity—and with an attractive new cover by Darrell K. Sweet, A Fine and Private Place is a decided outlier among both the preface novels and the novels published in the series proper. We’ve seen a wide range of genres—or, perhaps better to say, generic impulses—represented among just the eight novels covered so far in this reread series, often within the same novel, and therefore a wide range of genres informing the emergent meaning of “fantasy” in this crucial period of its “genrefication.” As I’ve noted before, the process of fantasy’s emergence as a mass market genre was slow and uneven, unfolding across the late 1960s and 1970s, with Ballantine, the BAF series, and, by 1977, their imprint Del Rey playing a major role in the genrefication of fantasy, along with a dozen other savvy publishers, as well as countless editors, writers, and fans, who collectively responded to and actively helped shape the newly salient genre.

A Fine and Private Place, though, is fantasy in the older literary sense that it is not realism, that it deals broadly with (supposedly) “non-real” things, like ghosts and talking birds, but it is very clearly not genre fantasy, science fiction, or even Gothic or horror or weird—all terms describing the texts that collectively, over the course of the BAF series, helped shape what the new market category of genre fantasy would mean and be by the end of the 1970s. It’s the kind of writing that gets its author into an MFA program; incidentally, Beagle won a Stegner Fellowship after the novel’s publication and studied creative writing at Stanford alongside Ken Kesey and Larry McMurtry. The novel has more in common with mainstream Saturday Evening Post or New Yorker literary fiction than with the emergent understanding of fantasy, making its continued presence on Del Rey’s fantasy list in the late 1970s and early 1980s a rather quirky inheritance of the genre’s development and a sign of the genre’s continued capaciousness.

To be clear, despite its greater affiliation with midcentury literary fiction than with the emerging fantasy genre, A Fine and Private Place is not not fantasy, as we now know it, even if it was unevenly and maybe even tentatively interpolated into the genre by Ballantine’s and later Del Rey’s marketing practices. But 1960 was a very different world for fantasy than 1969, demonstrating how much had changed in under a decade (to say nothing of how different things were a further decade later). As Timothy S. Miller notes in his critical companion to The Last Unicorn, Beagle’s editor at Viking complained that A Fine and Private Place was stuck between “two entirely different tones or conventions of fiction”: fantasy and psychological realism (7, quoting Kenneth J. Zahorski; here, “fantasy” is that older meaning: the thing that isn’t realism). While this intermixing of modes perplexed Beage’s editor, it’s not necessarily a negative and such play with tones, mode, convention—whatever you want to call it—is part of what makes The Last Unicorn such a rich text. In fact, A Fine and Private Place is a rather apt example of what Robert Scholes called “fabulation,” that literary form which sprung from midcentury mainstream literary fiction, played fruitfully with the fantastic and the science fictional in an otherwise realist mode, and presaged many of the later concerns of postmodernism. Still, for my taste, the novel never strays from being a middle-of-the-road literary fiction story that just happens to have ghosts and a talking raven.

The novel’s fabulations, its ghosts and talking raven are faintly tasted spices, salt and pepper on boiled chicken, nothing more: they help the “idea” of the novel along but they don’t even make the magical realist move to defamiliarize our understanding of realism, to challenge our or the characters’ sense of reality. The ghosts and talking animals could be interesting, could be an opportunity to probe the boundary between what is realism, what is fantasy, and whether the two are truly inimical as many critics uninspiredly suggest—and this sort of metafictional move would fit well with the highly accomplished metafantasy of The Last Unicorn—but the novel instead applies its ghosts to the dilemma of how sad it is to not have lived the life that now, in death, they realize they should have lived. Yes, that’s sad; yes, that’s a hard thing to learn; no, I’m not interested in reading a 19 year old narrate multiple characters ranging in age from their late twenties and to their sixties coming to this realization over the course of 250 pages. I might be, if Beagle had anything worth saying on these topics in 1960.

Beyond the banalities of its ghosts—which is to say: as a work of psychological realism—, A Fine and Private Place busies itself with endless witty observations about life and loss and it unprovokingly tackles “big questions” like death and love, without ever having anything truly significant to say about them (most teenagers don’t). It is safe, anodyne, nicely written, humorous, aloof, but never anything special, either in what it has to say or in how it uses its fantastical elements. Everything is a lesson on how to live (or die) well. Any ambiguity is a temporary flourish. It is indeed impressive as the work of a 19 year old. But, again, I have to emphasize that it is underwhelming to read as a 34 year old. And although I’ve long been obsessed with death (I used to lie awake at night as a child thinking about what death would be like, terrified at the prospect of simply not existing), I don’t find any of the novel’s principal preoccupations—or, maybe, its articulation of or its conclusions about those preoccupations—compelling.

The novel is about Jonathan Rebeck, a man who lives in an abandoned mausoleum in the (imaginary) Yorkchester cemetery in New York City, somewhere near the Bronx. Rebeck has lived there for 19 years (the age of the author, curious…); it’s less living, really, than staying/waiting, a liminality between life and death. He survives on donations from a talking raven, who brings sandwiches, clothing, newspapers, whatever Rebeck needs to keep going. Rebeck spends most of his time helping the ghosts of the dead pass on. He explains to them that they will eventually fade from existence as they lose interest in being human, as people stop coming by to visit, as they forget what it was to be alive. It usually takes a month or so. Rebeck explains all of this to two new ghosts: Michael, a thirtysomething history professor who died from poisoning, and Laura, a twentysomething bookseller who got hit by a truck. And then there is Mrs. Klapper, a widow whose husband, Morris, is buried in the cemetery. Mrs. Klapper meets Rebeck on one of her visits to his ostentatious mausoleum and the two form something more than a friendship, something less than a relationship over the course of the novel—despite the revelation that Rebeck is a homeless man living in the cemetery (he doesn’t reveal to her that he talks to ghosts). There is also Campos, a Cuban-American cemetery nightwatchman, who can also speak to the ghosts and teaches them Cuban folksongs.

If the novel has a central conflict, it’s when Michael and Laura will fade and cease to exist. Secondary to this is the question of whether Michael committed suicide, poisoning himself, or if he was offed by his wife, the stunningly gorgeous Sandra. His death is so suspicious, especially given their rocky relationship and Michael’s megalomania, that Sandra is put on trial. Details are relayed slowly throughout the novel by the raven, who brings news overheard on the radio and caught from newspaper headlines. In the meantime, while the truth of Michael’s death works itself out, Michael and Laura struggle with what it means to be dead, which amounts to a lot of dialogue about wanting (or not wanting) to remember life, the value of remembering what it was like to live, questions about whether they lived their life the way they should have, and so on. Eventually, the two fall in love. Or, well, it’s not clear if they fall in love or if they decide that being in love—or performing the memory of being in love—will somehow put off their fate, stop them from fading into nonexistence. There’s a great deal of back and forth between Michael and Laura on the subject of whether Michael loves Laura for who she is (or was) or because he needs to love her to stop from fading, to continue being human through the acts of loving. A good deal is said about what love is, whether it’s selfish, selfless, necessary, real, etc. It gets tedious.

While Michael and Laura are brought together by circumstance and need, so are Rebeck and Mrs. Klapper. Perhaps the best chapter in the novel is an extended look at Mrs. Klapper’s lonely life as a widow. She is rudderless without Morris, even a year later; she dreads waking up each morning, she runs monotonously through her routine and is absolutely unsure what the point of it is. She doesn’t know how to be herself. The novel seems to suggest, without ever outright asking, who Mrs. Klapper is without Morris. But she gets up, dresses, eats, and does chores nonetheless. The chapter is excellent because it demonstrates what Beagle’s is capable of when he attunes to a character. But I admire it most for its evocation of midcentury middle-class Jewish life. All of Beagle’s characters in A Fine and Private Place, even the raven, speak with roughly the same voice, the same aloof, smart, piquant style, with the exceptions of Campos, who hardly speaks, and Mrs. Klapper. Her speech patterns are clearly drawn from Beagle’s experience growing up Jewish in New York, a space where many of his elders no doubt spoke Yiddish, and Beagle includes not only a fair few Yiddishisms but captures that culturally specific way of talking. Moreover, Mrs. Klapper moves through Jewish neighborhoods, speaks with a Jewish butcher’s family, with hints at social concerns about intermarriage with non-Jews, and chats with old ladies who delight in imagining the synagogue services for their eventual deaths. It’s more Marvelous Mrs. Maisel than Chaim Potok, and it lacks Philip Roth’s anxieties about masculinity and sex, but it is quintessentially and wonderfully American Jewish. Mrs. Klapper is really the one redeeming thing about the novel. (Though I also have a fondness for the talking squirrel who invites the rude raven to a cookout.)

Eventually the novel meanders through its numerous faux-witty observations on life and extended dialogues about memory and death and love toward an end. Sandra is acquitted of murder when it’s discovered that Michael bought the poison himself. Michael not only committed suicide, he did it with the intention of framing Sandra for his murder. This means his coffin will be removed from the Catholic portion of the cemetery (suicide is an unforgivable sin), taken out of Yorkchester, and reburied at a cemetery for rejects in the Bronx. Since ghosts can only “haunt” the cemetery where their bodies are buried, this signals an end to Michael and Laura’s newfound relationship. At the same time, Rebeck decides he has to stop existing in this non-place between life and death, he has to overcome his fear of the world beyond the cemetery gates and return to life—maybe he’ll go back to his job as a druggist, maybe there’s a future with Mrs. Klapper. The novel ends with Rebeck and Campos digging up Laura’s coffin and reburying it in Michael’s new cemetery, with the hope that the two can continue together in the afterlife. And, finally, Rebeck goes off into the dawn with Mrs. Klapper on his arm, ready to face the world and start living.

I’ve said little about the talking raven because he serves mostly as a narrative means of bridging the epistemological gap between the cemetery and the outside, modern world. He’s a caustic fellow who doesn’t really like helping but helps Rebeck nonetheless because, in his view, there are people who give and people who take, who create or destroy, and ravens happen to be givers. It’s their nature; nothing to be done about it. So he helps Rebeck, just as Rebeck helps the ghosts pass on. The raven’s motivations mirror Rebeck’s own story. Rebeck was a giver. A druggist, once, who got caught up in making placebo “potions” and “charms” for clients who wanted more than the usual pharmaceutical drugs. He did it to help people, because he couldn’t figure out how to say no, and so destroyed his reputation and career, became homeless, and moved into the cemetery on a whim.

Giving and taking, creating and destroying, living and dying, remembering and forgetting—these are the parallel, motivating tensions in A Fine and Private Place. They are, to be sure, lofty ideas; the topics of great literature. They’re just a bit thinly handled in the novel, as is the novel’s commentary on modernity, which amounts to something like, “wow, modernity, huh? what a drag!” A fine sentiment, but thin, like the fading image of a ghost forgetting what it was to be alive.

As Miller notes, the novel’s major fantasy idea is “a conception of death as forgetfulness”: when ghosts forget what made them human, they fade and, we are left to imagine, ultimately die a true, real, final death. This, then, becomes a structure for the narrative as Michael and Laura strive to remember and to make new meanings in death, by learning songs from Campos, by playing chess with Rebeck, and finally by falling in love with one another. Beagle’s presentation of death as forgetting (whether being forgotten or forgetting oneself) is a trite but effective metaphor for understanding life as a necessary process of change and growth, but it never confronts what it means to truly forget, to be forgotten, to die eternally and finally.

Much of the early novel is concerned with Michael and Laura fading, with Michael especially fighting to remember, to “act” alive by willing his ghost form to appear as though it is walking or as though his face has a specific expression. Once Michael and Laura are committed to being together, to eking out whatever time they have left, the novel dispenses with the whole concern about forgetting. Michael and Laura being buried together, and Rebeck leaving the cemetery to rejoin the human world, take over as the driving narrative force. The suggestion, perhaps, is that these characters each seek ways to not forget, to build something new, and so to either keep living (in death, as ghosts) or to return to living (in Rebeck’s case, perhaps also in Mrs. Klapper’s). But Beagle loses sight of the novel’s fundamental concern with a final, true death.

I suppose this would be a triumphal, hopeful ending if the novel gave us any notion of its opposite. Forgetting haunts the novel, each ghost a fearful literalization of the idea, but it’s never really dealt with, never handled in the narrative. There is even, inexplicably, a ghost of Morris Klapper still hanging around, just barely, more than a year after his death—and he has no idea that his wife still visits his grave, that she remembers him. Why is he still around, then? Is it Mrs. Klapper’s devotion, which can also be read as a kind of stuckness, that keeps his ghost around? Is it something about Morris, his desire to stick around? Both questions provoke answers that invoke the other question, but neither is asked and Morris’s ghost remains an unfulfilling mystery. What an opportunity that would have been for Beagle to expand on the notion of death and forgetting, since Klapper still being a ghost challenges everything Rebeck knows about how and when ghosts “die.” What being dead means, ultimately, is unanswered—and, really, unasked—in this novel, which is sort of shocking for a novel about dying and lingering after death.

To be forgotten by others or to forget oneself and so truly die is, perhaps, the novel’s idea of the worst thing imaginable. But is that true? It’s a concern that comes from a place I don’t really get. It’s not something I worry about at all. So I have a hard time gelling with what Beagle is so preoccupied by. If his answer to death and memory had something to do with community—which, for example, the novel could suggest by turning to Mrs. Klapper and the meaningful relationships she has but ultimately spurns in her thriving Jewish community—instead of seeking meaning purely by finding the right heterosexual partner (and don’t get me wrong, my partner is my life), then I might be a little more interested in Beagle’s thoughts about making meaning in life.

But as is, A Fine and Private Place reads like the incessant hand-wringing of someone who is really worried that they will be forgotten, someone whose very youth prompts him to imagine that folks a little closer to the grave must be constantly worrying about death and the afterlife. This early iteration of Beagle, seemingly, can only imagine being a person and being remembered in highly individualist ways. He can’t imagine why Klapper might find meaning in her community, a bunch of aging fuddy-duddies who seem to be stand-ins for a teenager questioning how his grandparents can possibly enjoy the lives they live. In the most generous reading, the novel is a reminder to live the life you want to live, not the one you’re living because it’s the path you’re already on; live a fulfilling life—and find out what that means for you. But damn if that’s not the 1960 version of Live. Laugh. Love. I get it, it’s a valuable thing to remind oneself, but come on… Even trying to push a generous reading, A Fine and Private Place is for me a disappointing novel whose preoccupations and conclusions are frankly uninteresting, trite, and shallow.

All of my criticisms aside, Peter S. Beagle’s A Fine and Private is a finely written novel, if overly concerned with looking much smarter than it is. It’s a quaint and pleasant thing, not a literary travesty by any means. I couldn’t have written anything like it at 19. What’s most impressive, though, is that in just under a decade Beagle would go from penning this feint at literariness to writing a true masterpiece of twentieth century fiction and one of the most important fantasy novels, well, ever: The Last Unicorn. There are faint hints of The Last Unicorn in A Fine and Private Place, similar concerns with ethical life, with what we owe other people, with memory and being. But the similarities are pastel-painted ideas washed out by the neon vibrancy of Beagle’s later work. So I salute A Fine and Private Place as the match that lit the hearthfire of Beagle’s literary career.

In the next installment in the Ballantine Adult Fantasy reading series, I look at the second-to-last BAF preface book, Lin Carter’s nonfiction study Tolkien: A Look Behind The Lord of the Rings. That book put him on the Ballantines’ radar and proved that he had a deep historical knowledge of the texts that fit into the prehistory of this thing called fantasy. It’s the book that was ultimately responsible for bringing us the BAF series, that got Carter his “consulting editor” position, and that fleshed out a canon, a shape, and a history for the genre that would become fantasy.

To get notifications about new essays like this one sent directly to your inbox, consider subscribing to Genre Fantasies for free:

Beagle’s always worth reading, and I remember an undergraduate class focusing on first novels by eminent writers; I have to think this would be a good addition to it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

No doubt — that would be both a great and interesting course, and I think this would fit really well. For what it’s worth, despite disliking the novel, I still think it’s worthwhile and I imagine would teach well, too.

LikeLike

I’ve never read A Fine and Private Place, though I’ve owned a copy of that Ballantine edition for 50 years or so. (I do love The Last Unicorn, and many of his other stories.) Now I’m not sure I should!

I have long thought, based only on descriptions of the novel, that it bears a slight resemblance to a short novel by Robert Nathan, One More Spring. I met Beagle once at a convention, and he mentioned Robert Nathan as one of his favorites. I asked him if One More Spring was an influence on A Fine and Private Place, and he basically said something to the effect that it wasn’t a direct conscious effect, but perhaps it was somewhere in his mind.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Funny you should say that, Rich, because it’s the second time today I’ve heard that name and today is the first day I’ve ever heard it! A fellow fan on BlueSky noted the similarity with that same Robert Nathan novel and Beagle’s close influence. Very curious! Having never read Nathan, all I can say is I’m glad Beagle went in the direction he did over the course of the 1960s and ended up with The Last Unicorn.

I should also say that Farah Mendlesohn considers it to be an excellent piece of writing and is one of their favorite novels, so you might very well enjoy it. I never want my essays to put anyone off a book. This one just wasn’t for me.

LikeLike

If you want to read one Robert Nathan novel, I strongly recommend Portrait of Jennie, which is very moving indeed. And also short.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Rich — I’ll keep that on my radar! I always appreciate your insights and connections. I was recently reading over and enjoying your capsule reviews of various Thomas Burnett Swann novels, since I’m currently reading through all of his books.

LikeLike