Tolkien: A Look Behind The Lord of the Rings by Lin Carter. Ballantine Books, Mar. 1969. [My version: 1st printing, Mar. 1969]

This essay is part of Ballantine Adult Fantasy: A Reading Series.

Table of Contents

Ballantine, Lin Carter, and Adult Fantasy

Reading Tolkien: A Look Behind The Lord of the Rings

Parting Thoughts

Ballantine, Lin Carter, and Adult Fantasy

The penultimate book among the 18 Ballantine Adult Fantasy “preface novels” was not a novel at all, but Lin Carter’s nonfiction study of Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings, and the “epic fantasy” tradition to which he argued Tolkien belonged. Tolkien: A Look Behind The Lord of the Rings was one of two non-fiction titles published by Ballantine as part of or later associated with BAF, the second being Lin Carter’s longer and more sustained history of fantasy—and how to write it—Imaginary Worlds: The Art of Fantasy, published in 1973 as the 58th BAF volume. (Ballantine also published Carter’s Lovecraft: A Look Behind the Cthulhu Mythos in 1972, though it wasn’t associated with BAF.)

As I laid out in my brief history of BAF in the first essay of this reading series, Ballantine hit big with the “official,” Tolkien-approved mass market paperback editions of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, first published in that form in 1965 after Donald Wollheim’s attempt at Ace Books to produce “bootleg” mass market editions earlier the same year. In just two years, Carter tells us in Tolkien, Ballantine’s edition of The Hobbit had sold more than a million copies (14); the sales of The Lord of the Rings’s three volumes combined must have been astronomical. The sudden, explosive success of Tolkien after nearly a decade of mediocre sales in hardcover in the US suggested to Betty and Ian Ballantine that this kind of fiction, this kind of fantastical quest story for adults, could be big business.[1]

And so they sought not only to bring out more of Tolkien—which they did by publishing paperbacks of The Tolkien Reader (Sep. 1966), The Road Goes Ever On (Oct. 1968), and Smith of Wootton Major and Farmer Giles of Ham (Mar. 1969)—but also more work like Tolkien’s. They landed first on E.R. Eddison’s The Worm Ouroboros and the first two volumes of the Zimiamvia trilogy, Mistress of Mistresses and A Fish Dinner in Memison (which they seemed to initially think formed a trilogy with The Worm Ouroboros), and then on Mervyn Peake’s Titus books: Titus Groan, Gormenghast, and Titus Alone. After recovering these hardcovers from relatively obscurity and printing them in sleek mass market jackets with colorful covers by, in Eddison’s case, Barbara Remington, who was also their cover artist for their initial four Tolkien books, and Bob Pepper, in Peake’s case, Ballantine was beginning to have something of an emerging list of titles related to Tolkien on their hands.

Lin Carter came to the Ballantines’ acquaintance in 1967, partway through their process of finding titles like Tolkien’s. Since Ballantine was publishing Tolkien, Carter thought they might be interested in his “look behind” Tolkien from the perspective of someone who knew very well what kind of literature Tolkien had written and who felt very strongly that the reading public needed to know Tolkien didn’t come out of nowhere, fully formed, but belonged instead to a literary tradition—perhaps the most ancient one, in fact. Carter was the right person at the right time. In 1967, he was 37 years old, Columbia educated, a Korean War veteran, and a copywriter in New York City. He was a relatively well-connected science fiction and fantasy fan, friends with authors like L. Sprague de Camp, and known in the fanzine circles, where he occasionally wrote pseudo-scholarly articles on things like the origins of names in Tolkien’s novels. He was also a midlist writer of short, pulpy, sword and sorcery (and planet) fiction, mostly published by Wollheim at Ace Books (with 13 novels written between 1965 and 1969). And he’d worked with de Camp on the rather infamous Lancer re-editions and newly written pastiches of Robert E. Howard’s Conan stories—the success of which rode the wave of Tolkien’s popularity. Carter was one of those few genre fans who had read Tolkien in the mid-1950s—as one reviewer of Carter’s Tolkien put it, one of “us pioneers” happy “to gload [sic.] over” the mass popularity of “the Professor” (Paul Walker, Science Fiction Review, no. 39, Aug. 1970, p. 26).

Carter was incredibly knowledgeable, widely read, well-connected among sff fans (who were only really just beginning, in the 1960s, to sort out fantasy and science fiction as two rather discrete categories, well ahead of the publishers themselves), a prolific if mediocre fiction writer, and, as his book Tolkien would prove, not a bad non-fiction writer. Moreover, he had a specific vision of fantasy as a genre and the historical knowledge and rhetorical skill to argue that vision. The Ballantines found Carter and his vision of fantasy compelling. They agreed to publish his book—a huge win for Carter, given they were Tolkien’s official paperback publisher in the US—and eventually hired him as a “consulting editor” to identify, edit, and provide critical introductions for a line of books that would bring this newly market-proven category of “adult fantasy” into greater focus, while hopefully leading to a boatload of sales by giving the Tolkien audience something else to buy, read, love, and want more of. (It’s important to note that Betty Ballantine was the final authority on the developing fantasy list, just as she was on the sf side of things, and Douglas A. Anderson notes that without her judicious hand, BAF might very well have been a worse and messier collection of texts.)

In the meantime, while Carter finished his book on Tolkien, Ballantine published Eddison, Peake, and David Lindsay’s A Voyage to Arcturus (which appears not to have been intended to be related to the other books, given its initial branding as “A Ballantine Science Fiction Classic”). Carter’s Tolkien was published in March 1969, the month after Ballantine released its paperback reprints of Peter Beagle’s The Last Unicorn and A Fine and Private Place, both labelled “A Ballantine Adult Fantasy” on their covers, but not yet with the unicorn colophon and not yet as part of an explicit publication series. (The back cover of Tolkien bears the tagline: “The World of Adult Fantasy,” connecting both Carter and his book explicitly to Ballantine’s emerging conception of the genre.) Carter would later list all of these titles—the Eddison, Peake, Lindsay, and Beagle books, in addition to those Tolkien titles published by Ballantine between 1965 and 1969 and the final title in Eddison’s Zimiamvia trilogy, The Mezentian Gate, released in April 1969—as the “preface” to BAF, with his own study of Tolkien naturally included. Carter’s Tolkien is a linchpin for understanding the BAF series that would follow just two months later in May 1969, with the republication of Fletcher Pratt’s The Blue Star.

In my coverage of the BAF “preface novels” I notably did not cover the seven titles by Tolkien. In large part because Tolkien is already so widely discussed in the scholarship that he sustains a whole field of study, Tolkien studies, which exists in partial isolation from the rest of fantasy studies. And in lesser part because I wanted to detach from the orbit of Tolkien’s overwhelming gravitational pull, while still being able to acknowledge his incredible importance to the development of fantasy. To be clear, there was no BAF without Tolkien, and, even with his books republished by Ace and then Ballantine, there was probably no BAF without Carter’s Tolkien. No doubt, Betty Ballantine might have continued to publish texts like Eddison’s, Peake’s, and Beagle’s in small numbers, slowly growing the idea of “adult fantasy.” But it seems unlikely that the series would have come into existence without the fuel Carter added to Ballantine’s fire—in this case, the massive list of relevant titles he was already familiar with and likely already had in his personal collection (which seems to have been eclectic and voluminous).

Our understanding of fantasy, and even more so the creation of a market category for the genre, likely would not have happened without Tolkien, Carter’s study of his work, and the subsequent BAF series (we can add a dozen other sufficient and necessary conditions, of course, and will in due time). As Andy Sawyer noted in his review of Gollancz’s 2003 re-edition of Carter’s Tolkien, which was edited and “updated” by Adam Roberts, “anyone who discovered fantasy in or after the Seventies owes [Carter] a debt of immense proportions” (Vector, no. 234, Apr. 2004, p. 27).

Reading Tolkien: A Look Behind The Lord of the Rings

Carter opens Tolkien energetically, offering proof of the massive popularity of the author and The Lord of the Rings, while also establishing a “first in the door” narrative about “true” sff fans:

Suddenly it seems that nearly everyone is reading a very long and very peculiar book called The Lord of the Rings.

Science fiction fans were the first to discover it. They read and discussed it avidly in their small-circulation privately published amateur magazines called fanzines. No one even noticed or, if they did, probably did not think twice about it. As is well known, science fiction fans read that crazy rocketship stuff; if they can swallow that, they can take anything.

But before long, The Lord of the Rings was being talked about and argued over in Greenwich village espresso houses, then in high-school yards and on college campuses. It was even explored and sometimes praised by literary folk like Anthony Boucher and W.H. Auden, Richard Hughes and C.S. Lewis. And, finally, it somehow got into the hand of the “general reader,” who usually subsists on fat novels from The New York Times’[s] best-seller list.

The psychedelic-poster-and-button set (who came along after the book did) adopted The Lord of the Rings with little goat-cries of bliss. And today it is even mentioned at glossy East-side cocktail parties. In fact, everyone seems to have just completed it, has just begun it, or is just about to read it over for the second time. (1-2)

Carter makes clear that, although The Lord of the Rings began as a niche book beloved only by those who read “that crazy rocketship stuff,” it is now, at the end of the 1960s, a book imbued with significant cultural capital, loved among the hipster and hippies, the jet-setters and the trend-setters, the normies and the weirdos alike. People wear buttons with “Frodo Lives!” and “Go Go Gandalf!” and discuss Tolkien’s triple-decker romance of elves and hobbits and orcs and talking trees over cocktails.

Carter introduces Tolkien and The Lord of the Rings as something that needs to be known, if you want to be hip with the times—after all, The Lord of the Rings had become, by 1969, a “perennial favorite” “on the Ivy League best-seller list” alongside such timely novels as The Catcher in the Rye and Lord of the Flies (22). But despite or perhaps because of its incredible popularity, Carter also emphasizes that critics and readers have puzzled over just what kind of book The Lord of the Rings is: a heroic romance like Beowulf, or maybe “super science fiction,” as Naomi Mitchison called it, or perhaps an epic in the mode of Ariosto, Malory, Milton, or Spenser as various other critics proposed?

Carter’s Tolkien, thus, has two main purposes: first, to introduce readers to who Tolkien is and what The Lord of the Rings is about, so that they can have a fuller grasp of this important new literary classic, and, second, to demonstrate that The Lord of the Rings “is, quite simply, a fantasy novel” and is not, therefore, “unique and unprecedented in modern literature” (80). What “a fantasy novel” is, and the tradition to which it belongs, occupies roughly half of Tolkien. Elaborating, clarifying, and amending the meaning, scope, and history of “fantasy”—and Carter will bounce between calling it fantasy, epic fantasy, heroic fantasy, and heroic epic fantasy both within this book and across his non-fiction writing over the next five years—is, in essence, the project not only of Tolkien and Carter’s later book Imaginary Worlds, but could be understood as the purpose of the BAF series itself and Carter’s critical introduction to its volumes. Carter accomplishes the grand task of introducing Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings, and the history of ((heroic )epic) fantasy, covering some four thousand years of literary history, in just over 200 pages.

Following the introduction, the first three chapters operate as a biography of Tolkien, focusing on his academic career; a description of how The Lord of the Rings came to be written, with an emphasis on Tolkien’s participation in the Inklings (and countering the idea that anyone ever had an influence on him); and a look at the success of Tolkien’s novels “today.” This section lacks much of the detail and nuance that has made Tolkien studies such a valuable and necessary context for reading and understanding Tolkien and his many works, largely in the wake of his death and following the success of The Silmarillion (1977). Of course, this lack is understandable; Tolkien gave few details about his life while alive, insisting that it had no bearing whatsoever on what he wrote, and most of Carter’s sources are either an interview with Tolkien conducted by one of Carter’s friends in the Tolkien Society of America or hearsay from fanzines or letters by other writers. Carter discusses the Inklings at length, particularly Charles Williams and C.S. Lewis, quoting liberally from Lewis’s letters in order to gain a little insight into Tolkien. While these three chapters pale in comparison to what we know today—or even in 1977, following Humphrey Carter’s biography—it’s important to remember that all of this information was new in 1969 and was being offered to a mass audience, for the first time, at an entry price of just $0.95.

The next four chapters of the book account for roughly one quarter of Tolkien and are devoted to full plot summaries of The Hobbit and each volume of The Lord of the Rings. This may seem odd, but there are a few reasons why such lengthy summaries made sense in 1969. For one, this was not a book for specialists, who in any case didn’t really exist yet. Tolkien was a mass market paperback intended to be read by anyone with a vague interest in the topic. That it sold well is evidenced by the number of reprintings: at least 12 in seven years, or nearly two reprintings a year. Tolkien, we know, was big business for Ballantine and any book about Tolkien was implicated in that business. Carter’s book not only had to be readable by just about anyone, it had to appeal as a companion to a larger phenomenon. Indeed, Carter referred to Tolkien as “a popular celebrity, almost a folk-hero like Bobby Dylan” (29). No doubt there were many people who wanted to know what the whole Tolkien fuss was about, but who didn’t (want to) read the novels. And there were probably those who needed some explanation of or reminder about the plot. You might laugh at that, but Tolkien is not an easy read for everyone, and in the absence of online videos, podcasts, and articles to break down the plot in minute detail—think about how popular the brain-numbing “ending explained” genre is today—readers didn’t have much to supplement their understanding. A book like Carter’s, being among the first easily accessible such book, was no doubt a boon to many who found themselves suddenly in a culture where knowing about Tolkien helped them fit in.

Moreover, if you had read the novels, even if you had totally understood them and formed your own opinions, in the absence of easily accessible fan culture—outside of fanzines and fan clubs (which have limited appeal and access)—there was likely some pleasure in being able to re-experience the novels by reading such a detailed summary. For the same reason, people still read recaps and blog posts and watch YouTube video essays about things they’ve already read and seen. Most fans like to hear what others say about a thing they like; how another person describes the plot is crucial to knowing if you’re on the same page: it’s an important part of cultivating a fan community. What Carter does with his lengthy summary seems weird and perhaps a bit overkill to us, but in the late 1960s/early 1970s it served a very different purpose. That his summaries were not as odd then or as pointless as we might imagine them today—especially those of us who grew up on the internet, in a culture of online fandom, and in the wake of Peter Jackson’s trilogy—is evidenced in the overwhelmingly positive response to Carter’s book. Of the five contemporary reviews I’ve read from fanzines and sff magazines, all are impressed by Tolkien, and most comment appreciatively on the helpful plot summaries.

Following his summaries, Carter gives us two short chapters of pseudo-analysis with an emphasis on Tolkien’s own ideas about his books. While Carter surveys the plots extensively, he offers very little in the way of analyzing the book’s themes or ideas, though he occasionally reflects on the beauty of Tolkien’s language and the affective power of his writing. His two chapters of analysis or theory are about, first, whether The Lord of the Rings is allegory or satire, and, second, Tolkien’s own theory of the “fairy-story.” These two chapters provide some vague analytical frames for understanding Tolkien—though Carter does a piss-poor job of applying those frames, of showing how we might use the concepts of allegory, satire, or the fairy-story to better grasp what’s going on in The Lord of the Rings—and set up important questions about the kind of book The Lord of the Rings is, which occupy the following four chapters.

I won’t keep you in suspense: on the question of whether The Lord of the Rings is satire or allegory, the question is not only no, it’s a resounding “why the hell would it be?!” Carter, you see, is very much averse to allegory and satire. He brings this up in his critical writing wherever the specter of either form raises its head. I quoted above Carter’s claim that The Lord of the Rings “is, quite simply, a fantasy novel” (80). The language here was purposeful. Carter juxtaposes this idea of a fantasy novel, pure and simple, against claims by critics that there is something Miltonian or Spenserian about The Lord of the Rings. It’s an almost offensive idea to Carter: “the trilogy is not in any way either a satire or an allegory, but a romance pure and simple” (80). He clarifies: “Tolkien is merely telling a story, and it has no overtones of symbolic meaning at all” (80). Absolutely hilarious stuff. I quite literally burst out laughing when I read this. Not only for the claim that “romance pure and simple” is definitionally non-allegorical or non-satirical, when the romance—and particularly the medieval and early modern heroic romances in the Arthur and Charlemagne cycles that Carter will go on to write about at such length in the coming chapters—is among the most allegorical forms of literature, but also the idea that Tolkien is “merely telling a story” and that, as such, it has no symbolic meaning. Absolutely what the fuck?

Of course, Carter believes he has good reason to say this. After all, Tolkien regularly rejected allegorical and symbolic readings of his own work. It was not about the Cold War, for example, or about Britain versus the Nazis (WWII) or about Britain versus the German Empire (WWI), or about anything: just a plain old story of good versus evil—which, of course, is somehow not allegorical. For Carter, “The significant element [in determining if a narrative is allegory or not] would be the author’s stated intent” (82). To make his measly point, Cater cites Spenser’s Elizabethan epic poem, the highly allegorical The Faerie Queen, which according to Carter was a failure and killed the genres of epic poetry and of romance alike (apparently) because its allegories were so obscure that Francis Drake couldn’t understand them. For Carter, then, the object lesson is that “symbolism adds up to a total waste of time on the author’s part if the reader is unable to get the point” (83). To that end, Carter quotes Tolkien as saying The Lord of the Rings isn’t “about anything but itself” and “It has no allegorical intentions, general, particular[,] or topical, moral, religious[,] or political” (84). Sorry, Tolkien, but that’s silly. Thankfully, such attitudes have not remained the mainstream in literary studies generally or Tolkien studies more specifically. Authors’ stated intentions are interesting but are hardly the final word in any good practice of literary criticism.

What’s particularly fascinating about Tolkien’s oft-stated allergy to the idea of having ever been influenced by anyone or having ever had a single allegorical intention across his many decades of writing, is that his theory of the fairy-story—which is often read as a theory of fantasy (see Jamie Williamson’s discussion on this point in The Evolution of Modern Fantasy, 20–26; for another understanding that puts Tolkien appropriately in the context of the romance, see Kevin Pask’s The Fairy Way of Writing)—is explicitly implicated with allegory. After (apparently) establishing the lack of allegorical, satirical, or, hell, any symbolic meaning at all in The Lord of the Rings (which might make us wonder, then, why the novel resonates so powerfully among so many different readers, where Carter sees merely an adventure yarn), Carter turns to Tolkien’s theory of the fairy-story and an account of his lecture-turned-essay “On Fairy-Stories.”

Tolkien’s essay is a truly wide-ranging bit of writing for such a short piece. It’s about the operation of the “fairy-story (or romance)” in literature, about conflicts between good and evil seen through the lens of the such stories, about the appropriate structure for such narratives (including his ideas about joy and eucatastrophe), and about his theory of sub-creation. Tolkien’s understanding of the fairy-story is explicitly interested in all of this as a kind of intellectual and even moral operation within the context of his Catholic worldview. Tolkien was very much invested in allegory of some kind, whether he admits it or not, and he clearly felt that his writing had not just symbolic overtones but explicit symbolic meaning and purpose. Indeed, if Tolkien didn’t think allegorically, with either politics or religion in mind, he would not have revised his presentation of the dwarves to be less anti-Semitic or worried over the implications of his orcs having souls. Nor would he have been so concerned with such big issues as war, nature, and industrialism. Even Carter, strangely, asserts that “the moral element [of The Lord of the Rings] is plainly obvious” (92).

With Tolkien’s theory of the fairy-story—which amounts, really, to Tolkien’s ideas, both analytic and idealized, about the role of the fantastic in the romance and in fairy tales; again, in Tolkien’s own words: “fairy-story (or romance)”—as a jumping off point, Carter establishes that The Lord of the Rings is fantasy. Fantasy, for Carter, is a broad category of literary “make-believe” (81). To it belong horror, science fiction, and authors as diverse as “Rabelais, Chaucer, Goethe, Milton, Cervantes, Swift, Shakespeare, Voltaire, Byron, Ariosto, Keats, Flaubert, Spenser, Dante, Marlowe, and even a Brontë or two[…]—to say nothing of Stevenson, Kipling, Doyle, Wilde, Haggard, and Anatole France” (81). Fantasy, described this way, is that older understanding of fantasy that I have discussed in several previous essays (e.g. here), where fantasy is, namely, understood as that which is not strictly (or totally) “realism.” Hence Tolkien’s reference to the uses of fantasy in the fairy-story, where he, too, like Carter, means something like “imaginative literature” or, most simply, “make-believe.” As Carter puts it rather portentously, “Quite a case could, as a matter of fact, be made for the fantasy tale as one of the major areas in world literature” (81). Fantasy, for Carter, is a ubiquitous part of literature—a “mode,” if you will, of writing and representing the world in (supposedly) non-realist terms.

But what kind of fantasy is The Lord of the Rings? After all, for Carter,

fantasy is a catch-all term that encompasses everything from Homer and Swift and Kafka to Poe, Milton, and The Turn of the Screw. Science fiction is a part of fantasy; so is the literature of gothic horror and even children’s books like L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and its forty-odd sequels. Any genre so broad as to include both Dracula and Utopia demands further redefining. (94)

Tolkien’s trilogy is most cognate, according to Carter, with the fantasy of epic poetry because of the “size,” “concept,” “sweep,” and “grandeur” of its narrative (95). He thus proposes we call The Lord of the Rings “epic fantasy.” The next four chapters are devoted to outlining the history of the literary tradition that informs and transforms into the “epic fantasy” of Tolkien and his immediate forebears.

The first of these historical chapters is about the ancient epic tradition, from Gilgamesh to Homer, with the emphasis on Homer’s overwhelming influence and the creation of an epic cycle amounting to more than a dozen (mostly lost) ancient Greek epics about the Trojan affair. For all his reading, Carter seems to have mostly missed the argument, already established by 1969, that the epic cycle emerged from a complex oral epic poetry tradition common to and practiced for thousands of years across most of Eurasia. Moreover, Carter says some quite strange things about ancient humans, e.g. that “man” was, in Homer’s time, “still involved in the world of his own imagination” (97). This amounts to the fact that, apparently, ancient humans hadn’t really figured out much about the world (i.e. scientifically), so, “like a fantasy writer mapping out an invented worldscape, man built up his own picture of his world” (97). This is a horribly shallow view of humanity prior to…when? The Enlightenment? It’s not clear in Carter’s writing when he thinks humanity stopped living in a world of his imagination, but it’s very clear that Carter does not understand that everything ancient humans knew was as much derived from a combination of received knowledge, experiential learning, purposeful experimentation, and imagination as our own episteme is. Carter’s poor understanding of the ancient world aside, he (dubiously) claims that epic invented “The concept of the story laid amid purely invented surroundings” (107) and supplied two themes or structural tropes that traversed time and literature to inform the creation of epic fantasy: (1) a war between two sides and (2) a quest. By the dawn of the Middle Ages, then, “fantasy” had: invented settings, wars between two sides, and quests.

Carter continues in the second historical chapter to cover the French chanson de geste and the equivalent Spanish, Portuguese, and Italian traditions of medieval heroic epic poetry. His focus here is mostly on the Matter of France, i.e. the stories of Charlemagne and his knights, notably in the eleventh-century La Chanson de Roland. In Carter’s reading of the tradition, the chanson adds the elements of “cognomial” weapons (i.e. important swords with names and histories), the supernatural (by which he means fairies, elves, dwarves, etc.; these are somehow different from “pagan” gods or things like fauns, minotaurs, the hydra—I don’t know how and Carter doesn’t say), and magical artefacts. Like the previous chapter, this is a competent survey of some relatively obscure texts to most readers who haven’t studied ancient and medieval literature. But Carter does not pull this off without saying, again, some weird stuff. Most egregiously, he frames the development of the medieval tradition he surveys as a process by which “the formal [ancient] epic had decayed into the chanson, which soon descended into [later medieval] romance” (119). I truly cannot understand the use of decay and descend as descriptors for the development of any literature tradition, let alone these ones, and Carter spends a good deal of time in this chapter and the next bemoaning how terrible, boring, uninventive, and derivative so many of these texts are. He later uses terms like “corrupt” (130), “bastard outgrowth” (131), “hopelessly mixed up” (132), and “infected” (132). It’s incredibly annoying; it says nothing about the value of these literatures to their writers and audiences; it betrays an air of pompousness that, I think, makes Carter look like a douche; and it’s richly hypocritical coming from a writer who champions forms of literature—not just epic fantasy, but sword and sorcery—that have been decried as degraded forms of subliterature.

When chanson “descended” into the medieval and early modern romance, the topic of his third history chapter, “fantasy” now had: invented settings, wars between two sides, quests, cognomial weapons, supernatural beings, and magical artefacts. Most of Carter’s chapter on medieval and early modern romance is actually spent discussing the truly obscure—to us, at least, but once phenomenally popular—Amadis cycle, which spawned countless sequels and was ultimately lampooned by Cervantes in Don Quixote, and with the more familiar Orlando Furioso by Ariosto. In Carter’s telling, the heroic romance added magic and magic users, namely wizards, to the fantasy tradition. According to Carter, magic was “foreign to the spirit of the classical epics” and so was a completely new addition to the romance (122). This is, patently, false. Carter counters any suggestion of magic in the ancient world by saying that magic in the ancient world was religious in nature, since it had to do with the gods. For Carter, magic is a “debasement” of religion, the use of which in romance reflects its own debasement of the classical epic. The fuck?

Carter really struggles to make his leaps in logic work in order to describe the progressive growth of a formula that will form the epic fantasy tradition, while at the same time forwarding an argument that the perfect, ideal form of the classical epic was being degraded over the millennia. I can’t read this as anything other than an attempt by Carter to emphasize to his readers how deeply knowledgeable he is, that he’s smart enough to have read widely across these traditions, such that he’s able to smugly tell you that none of it is as good as the originals. It’s a really weird rhetorical move and completely unrelated to telling the story of a developing fantasy tradition. And many of his claims are at best misunderstandings of history and context, with the latter abandoned in order to recast the former so that it fits his narrative.

In the final of his four history chapters, Carter pulls us forward several hundred years to “The Men Who Invented Fantasy” in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, to figures like William Morris, Lord Dunsany, and E.R. Eddison. In his narrative, these authors inherited the elements of the preceding fantasy tradition—namely: invented settings, wars between two sides, quests, cognomial weapons, supernatural beings, magical artefacts, and magic users—and combined them with the “modern novel” and with (what he calls) Morris’s great invention, a fully invented secondary world, to create the first texts we can call “epic fantasy” (Carter seems to imagine Morris as a maverick with no precedent at all; see Williamson’s The Evolution of Modern Fantasy for better context).

Carter surveys the biographies and major works of Morris, Dunsany, and Eddison. Carter concludes the chapter by naming a few other relevant writers working in the years between Eddison’s first novel, The Worm Ouroboros, in the 1920s and Tolkien’s trilogy in the 1950s: Fletcher Pratt, L. Sprague de Camp, and Mervyn Peake. Elsewhere, Carter mentions James Branch Cabell, Poul Anderson, and Robert E. Howard and the sword and sorcery tradition, but Carter makes clear that he thinks the latter doesn’t count as epic fantasy. Of these, the inclusion of Peake makes no sense for his epic fantasy argument (at least, it makes no more sense to include Peake in this definition that has nothing to do with his books, but to cite this definition of epic fantasy to then exclude Howard), and I have to imagine that Peake was likely included—perhaps suggested by Betty Ballantine?—to tie the Gormenghast books more explicitly to the BAF series that was just about to launch.

Of course, very few of these authors’ texts employ all of the elements of “epic fantasy” Carter has been tracing the development of. Tolkien’s trilogy does, though, which makes clear that Carter constructed the epic fantasy tradition retroactively with Tolkien as a starting point, with The Lord of the Rings as its final form. This does make some sense, after all, but it raises significant questions about the history he tells and about his interpretations of those literary traditions (I’ve already raised a few concerns about his history, but I could easily go on for longer). Would his interpretations be the same even if he didn’t have Tolkien as the end point? And what does that tell us about the staying power of this definition (and history) of epic fantasy? Most importantly, it’s unclear why Carter focuses so extensively on the literary traditions of medieval Romance language speakers, and why he does not instead (or equally) survey medieval Germanic, Norse, Celtic, or Anglo-Saxon literary traditions, given the obviously greater influence of those on both Tolkien and these “men who invented fantasy.” Yes, Carter does this to some extent in the remaining three chapters—which are mediocre source studies of plot elements, names, and people, places, and things in The Lord of the Rings—but it seems odd to devote so little time to the traditions that had the greatest influence on these writers. If James Branch Cabell had been the focus of this book, the starting point for this tradition of fantasy, from which Carter wanted to work backwards to understand how his brand of fantasy emerged—then the focuses of Carter’s historical chapters might have made a little more sense.

As a final thought about Tolkien, I want to say that Carter rarely wastes an opportunity to talk about himself and his own genius (this issue is indulged to greater extent in Imaginary Worlds). The postscript introduces a few authors who were working in the epic fantasy tradition in the late 1960s, including Carol Kendall, Alan Garner, and Lloyd Alexander (all children’s writers, interestingly, given the “adult fantasy” angle), and he vaguely gestures at two unnamed men working on epic fantasy novels. But he ends the book with this gem:

I have myself for some ten years, off and on, been puttering with an epic fantasy of enormous length in the Morris-Dunsany-Eddison-Tolkien tradition. When and if it is completed and published, it will be called Khymyrium: The City of the Hundred Kings, from the Coming of Aviathar the Lion to the Passing of Spheridion the Doomed. (201)

It is a recurring theme that, given the opportunity, Carter toots his own horn, even including his own short stories in every anthology he edits—both for BAF and after, for example in his The Year’s Best Fantasy anthologies for DAW. Unfortunately(?), Khymyrium was never finished.

Parting Thoughts

By the end of Carter’s Tolkien: A Look Behind The Lord of the Rings, readers have something like a working definition of fantasy—i.e. the imaginative literature of “make-believe,” which is one of the fundamental genres of literature across time and space—and a more delimited idea of “epic fantasy” as a tradition that emerged out of the ancient epics, chanson de geste, and medieval and early modern romance, and which is identifiable by its story of heroes living in invented settings, fighting a war between two sides, going on a quest, wielding cognomial weapons, engaging with and probably fighting supernatural beings, encountering magical artefacts, and dealing with magic users, who may be friend or foe. Many of the texts Carter includes under the umbrella of epic fantasy fit uneasily in the category, while things he explicitly excludes (like Howard and sword and sorcery) fit quite well. Carter’s account of the tradition to which Tolkien belongs is essentially a practice in vibes taxonomy. And while his book annoys me in its particulars, especially his poorly argued literary history, I recognize that the work Carter did in Tolkien was an important step in trying to delineate something—a tradition, a genre, a literary form?—we all know is real.

Over the next five years, Carter would continue to wrestle with a number of questions that are suggested in Tolkien but often pushed under the surface in an effort to present a clear, simple, final definition. But questions still linger and would animate both the 66 critical introductions he wrote to BAF volumes and his later study Imaginary Worlds. Across these critical spaces, he would ask and occasionally answer: What is fantasy? What is epic fantasy? Is it the same as heroic fantasy? Is it the same as what, say, Peake or Cabell or Hope Mirrlees or George Meredith or George MacDonald wrote? If so, how do we deal with the vast differences between their texts? If not, why do their texts seem to go together anyway? (Do they even go together?!) How do we account for and classify historical forms that don’t fit what we now call “epic fantasy,” but which are clearly adjacent in some way? These and more questions await us as we continue forward into the BAF series proper.

Looking beyond BAF and our project here to understand the emerging market genre of fantasy in the very moments that it came into being through the arguments and texts presented in books like Carter’s Tolkien, it still remains for us to ask what good is this book—as a study of Tolkien or of fantasy—today? From the perspective of 60 years, Carter’s Tolkien is a rather mediocre study of the author and a rather unimpressive argument for the history of fantasy, at least in its specific claims, but it is nonetheless a highly accomplished book for its time and, even for today’s readers, it offers a wealth of knowledge about sometimes quite obscure texts (some of which still don’t have good, easily accessible editions in English translation).

Still, the unparalleled history of fantasy remains Jamie Williamson’s The Evolution of Modern Fantasy, which takes the BAF as its frame, challenges Carter’s claims and assumptions, and offers an unsurpassed and, most importantly, historically contextualized survey of hundreds of novels that became the taproots of the modern market genre that emerged with the help of BAF. There are, of course, other excellent histories of fantasy—like Edward James and Farah Mendlesohn’s A Short History of Fantasy and Adam Roberts’s recent Fantasy: A Short History—but none as erudite and important, I think, as Williamson’s (though he only goes up to the end of the 1980s, which is great for our purposes in studying BAF but not great for understanding where genre fantasy goes once it emerges and becomes a stable genre category).

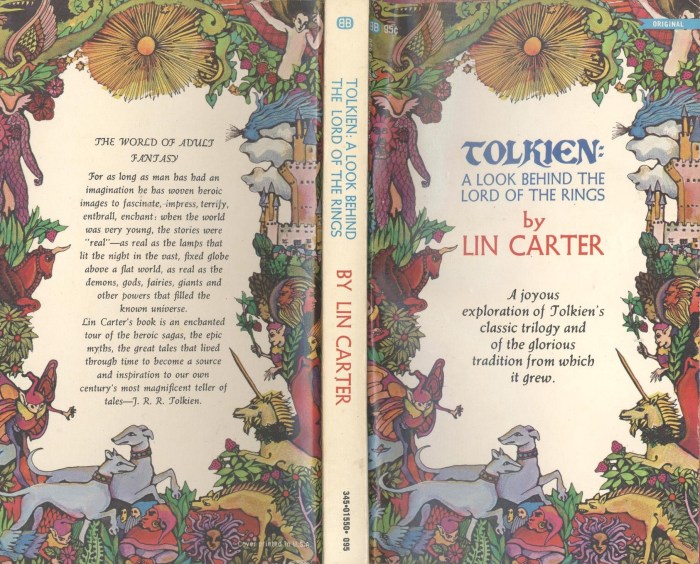

For Tolkien studies, however, you need hardly look far to find a dozen and more excellent scholarly books—not to mention hundreds of scholarly articles—on the author and his works, from general introductions to hyper-specific monographs on niche topics, from detailed source studies to applications of every kind of analytic frame you can name. Tolkien is, without a doubt, one of the most studied authors of the twentieth century. High praise goes to Carter for getting in at the start, exciting people’s passions for Tolkien, and hazarding a number of claims about meaning, themes, and sources. To be sure, Carter’s was not the first book about Tolkien, having been published quickly on the heels of Tolkien and the Critics (1968) and William Ready’s Understanding Tolkien and The Lord of the Rings (1969). But given that Carter’s Tolkien was released by Tolkien’s official paperback publisher—with a lushly painted cover very much in keeping with the emerging aesthetic of Ballantine’s fantasy titles, with a frame in the style of Remington’s Eddison covers (by an artist only identified as “Baslove,” about whom I can find no information)—it was probably the most widely read book on Tolkien until Paul H. Kocher’s Master of Middle-Earth: The Fiction of J.R.R. Tolkien (Houghton Mifflin, 1972 in hardcover; Del Rey / Ballantine, 1977 in paperback). Carter’s book was later packaged in a 1977 paperback box set with Kocher’s study, Humphrey’s Tolkien biography, and Robert Foster’s A Guide to Middle-Earth, signaling its continued relevance to the Tolkien-hungry public in the very year that The Silmarillion and a number of other fantasy bestsellers dropped. But in the decades since the publication of Tolkien: A Look Behind The Lord of the Rings, Carter has long been passed, lapped, and made largely irrelevant as a Tolkien critic. Though his book might work well as a curiosity for the general reader and certainly for a younger reader newly introduced to Tolkien.

Next up in the Ballantine Adult Fantasy reading series, we take a look at The Mezentian Gate, E.R. Eddison’s posthumous novel and the final book in the Zimiamvia trilogy, as well as the last of the BAF preface novels.

To get notifications about new essays like this one sent directly to your inbox, consider subscribing to Genre Fantasies for free:

Footnotes

[1] For a very readable look at BAF and its place alongside other efforts to canonize/concretize sf, horror, and weird fiction, see the blogger Scriblerus Club’s introduction to BAF, which quotes copiously from relevant sources, including Jamie Williamson, whom I regularly reference. Scriblerus Club’s essay was published the same month I began this BAF reading series with my post on The Last Unicorn, but I only just found it while researching this piece on Carter’s Tolkien and I think it’s a great work of fan-scholarship that emphasizes, smartly, the importance of the genre the Ballantines, Lin Carter, and BAF helped create.

I remember reading this early in my graduate work. I’m aware now that there was a solid stream of Tolkien scholarship when I was in college, but even at the time, it wasn’t as, shall we say, prominent as it has since become. Carter wasn’t quite my introduction to the field, but I still found it a useful touchstone, and I still think his comments about early reception (I paraphrase: professors read it early on to feel a bit dangerous but turned away from it once undergraduates started thinking Tolkien was cool) are telling.

Admittedly, I’ve not read Carter since my early graduate days, and those are…a little while back.

LikeLike