The Historian by Elizabeth Kostova. Little, Brown, 2005.

This essay is a companion to an episode of the A Meal of Thorns podcast.

Table of Contents

Finding the Book

Reading The Historian

Kostova’s Spectres

Parting Thoughts

Finding the Book

In the beginning was the word: Drakulya. The word and the dragon. Printed from a woodblock engraving at the center of a book hundreds of years old, discovered under mysterious circumstances by a historian. That book haunts the historian, challenges them professionally, calls them to bring all their skills as a historian to the task of pursuing the mysterious book to its source, and upends what they thought they knew about the boundary between the real and the unreal, between natural death and the supernatural persistence of some beings beyond death.

I, too, am haunted by a book. A book I once thought was good. Very good, in fact. So good I told people it was my favorite novel. For a decade. A novel I’ve read more than any other: four times between 2010 and 2014, once again in 2019 (when doubt began to seep into the cracks and the facade appeared to crumble), and now for the sixth (and perhaps final) time. And like many who revisit a beloved story from their past, a text whose rose-colored memories they previously had no cause to question, and which seemed in some way to define them, was the key to getting how they saw the world; and like those who discovered instead that the text is not what they remember, maybe it’s not even very good, or maybe it no longer speaks to how they understand themselves—now I, too, find myself disappointed by this book that once truly meant something to me.

I’m talking about Elizabeth Kostova’s debut novel The Historian, now twenty years old. A vampire novel that desperately does not want to be a vampire novel. A novel that imagines what if Bram Stoker’s Dracula, but flat, atmosphereless, and twice as long? A novel whose rights sold at auction for $2 million while Kostova was still finishing her MFA program in creative writing at the University of Michigan. The first novel ever by a debut author to land on the New York Times bestseller list the week of its release. A novel that publishers and studios thought might be the cultural successor to Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code phenomenon. A novel that sold like crazy. A novel you have probably never heard of—unless, like me, you track every vampire or Dracula novel published, or have plumbed the depths of dark academia reading lists. A novel that started an author’s career with a monstrous bang and led to two further, quietly ignored novels. A novel that never got its movie adaptation and never led to a Brownian cultural phenomenon (which still continues, with Brown’s September 2025 release of yet another bestselling novel featuring “symbologist” Robert Langdon).

In my college years, The Historian was among the three novels that influenced me to such a significant degree that they each charted a part of the path that would bring me, albeit windingly, to my vocation as a critic and historian of fantasy, horror, and science fiction. These were, in the order of my reading: the June 2010 translation of Jules Verne’s The Castle in Transylvania (published in 1892 as Le château des Carpathes), then Kostova’s novel, and finally Edgar Rice Burroughs’s A Princess of Mars (1912). It is an eclectic and somewhat obscurantist list; of them, only Burroughs’s novel has anything like canonicity in our conception of genre history, even if Burroughs is rarely read today (and for some good reasons). But this obscurantism was not purposeful; each of these novels was found by happenstance, almost as if set before me to discover…

In the case of The Historian, I found the novel during the summer of 2009 while accompanying my mother to an educators-only Scholastic Books warehouse sale. The novel struck me, for some heady mixture of reasons, and I walked away from the sale with only my hardcover copy of The Historian and the sense of having found a deeply meaningful book. Still, I didn’t read The Historian until more than a year later, after reading Verne’s The Castle in Transylvania, but on finishing the novel I was thoroughly obsessed with Eastern European history and signed up for the next semester’s Russian course. Not because the novel had anything to do with Russia directly, but because Russian was the only Eastern European language offered at my regional state university. Close enough, I thought. And within a year, at the suggestion of my Russian advisor, I was studying in Kosovo so I could learn Albanian, too. Again, not directly related to the novel, but even closer. By 2013, one of the two majors I graduated with was Russian linguistics—the other, anthropology. From The Historian I took my love of vampires and of Eastern Europe, two defining interests that have not flagged, only transformed in interesting ways. Later, it was the influence of Burroughs’s book that turned me on to popular genre fiction, pushed me away from graduate school in anthropology or linguistics, and instead prompted me toward an English PhD, so I could study the cultural history of genre fiction.

As Christine Smallwood so eloquently put it, “[c]riticism is an act of autobiography (hat tip to Molly Templeton’s essay on the death of criticism for introducing me to Smallwood’s). I never try to hide this fundamental fact in my writing, but some books carry more autobiographical weight. The Historian, both as a novel and for its effects on my being, still haunts me, and deeply so, only now my understanding of the vampire novel and of the history of horror and the Gothic is so much greater, that I cannot help but compare The Historian—and not favorably—to all that contextualizes it within literary and genre history. But The Historian was the catalyst for my love of horror and the Gothic, it’s an inextricable part of my story, it’s the reason why someday I hope to write a literary history of American vampire fiction, and by extension it’s the canvas on which all my other bucket list horror fiction projects are sketched.

In this essay—a companion to my discussion of this novel on the Ancillary Review of Books podcast A Meal of Thorns, hosted by Jake Casella Brookins—I return to Kostova’s The Historian. This work is a shamelessly autobiographical act of criticism that challenges me to ask what I saw in this book, what I see now, and what has changed.

Reading The Historian

Kostova’s The Historian is—or at least borrows elements from—many kinds of novels: vampire, Gothic, historical, travelogue, epistolary, campus, mystery, adventure, thriller. Kostova claimed her main influences were Victorian, namely: Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (1847), Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone (1868), and Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897)—a fitting set of intertexts reflected in the novels Kostova homaged in writing The Historian. The novel was also inspired by autobiography: Kostova’s father, an academic, told her vampire stories in her youth and she spent several months in 1972 in Ljubljana, Slovenia, then part of Yugoslavia, while her father was on academic exchange; this inspired a longterm interest in the Balkans and Eastern Europe, which she studied in college and travelled through in the late 1980s, and she ultimately married a Bulgarian man.

Kostova spent roughly ten years writing The Historian, beginning in 1994, and finished the novel while earning her MFA. The publishing rights sold at auction for $2 million, an astronomical sum for any book contract (see this list of largest book deals), let alone for a debut author. And the book was a bestseller, moving more than a million copies in the US alone in just a few months, thanks in large part to publisher Little, Brown’s $500,000 marketing campaign (and helped by aggressive discounts from bookstore chains, no doubt reflecting purposeful discounts from the distributor to encourage sales). Rights were sold for 28 languages and the film rights sold for another $2 million (though a film has obviously never been made). This was the era of Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code and comparisons between the two were a regular feature of press responses, with The Guardian, for example, calling Kostova “Bigger than Dan Brown.” But Kostova vehemently opposed such comparison on the grounds of her novel’s literary quality and her rejection of action as the driving force of fiction.

In a 2006 interview with The Age, Kostova claimed The Historian was partly written to address what she understood to be a dilemma of recent historical origin for fiction:

It does seem to be a dichotomy we fell into in the late 20th century: why are we constantly feeling we have to choose between action books that are formulaic and commercial, or beautifully crafted, detailed books that don’t put plot in a very strong place?

The solution, she felt, was a return to the Victorian novel:

The Victorians did such a great job, and I wanted to see if I could write a book that was allowed to take its time if it needed to.

Part of the joy of a Victorian novel is the setting and the analysis of character, but at the same time you really want to know who gave Pip his inheritance, or where the moonstone is.

The Historian certainly takes its time at a whopping 642 pages in hardcover and 720 pages in trade paperback, and a good deal of those pages are dedicated to a mixture of scene setting—which Kostova has certainly mastered—and charting the twists and turns of a historical mystery unfolding across three timelines: Bartholomew Rossi in the early 1930s, Paul and Helen in the early 1950s, and the unnamed teenage narrator, daughter of Paul and Helen (and granddaughter of Rossi), in the early 1970s. The novel is positioned as a narrative of what happened in the narrator’s youth, when she was c. 17, and is framed by the narrator’s occasional reflections on her life since the culminating events of the early 1970s and on her career in academia, decades later, sometime in the early 2000s.

The 1970s timeline follows the unnamed teenager, whom I’ll simply call Narrator, as she learns about the mysterious events of her father’s past, leading to the discovery of her dark lineage and the truth of her mother’s disappearance (whom she thought had died from sickness). Narrator offers us this story after the fact—that is, The Historian is, within the world of its novel, a true story of what happened, a classic Gothic convention that presents readers with a “found” story that, like Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto or Stoker’s Dracula (among many others), leans upon readerly good will to take the fantastical events as “real.” As such, the novel includes not only Narrator’s story but letters written by Rossi, stories recounted from her father’s tellings, her father’s own diaristic memory of the events twenty years earlier, postcards from her (once-thought-dead) mother, and excerpts from medieval and early modern manuscripts, including folk songs (all invented by Kostova). The Historian is a multimodal novel that blends literary forms in much the way Stoker did—most especially through letters, diary entries, and newspaper clippings—to offer something like a seemingly holistic picture of the narrative’s events, validated by multiple perspectives and a mountain of evidence, and very much in imitation of the historical research process that emphasizes primary documentation.

The story of the novel begins with Narrator’s discovery of a strange book hidden on a top shelf (near a Kama Sutra) in her father’s study: an early modern book, completely blank but for a single woodcut printing at its center: a fierce dragon, its wings unfurled, its tail curling to a deadly point, and bearing a single word: Drakulya. When Narrator confronts her father about this book, Paul reveals that Dracula—known to history as Vlad III or Vlad Țepeș (c. 1428–1477), and colloquially as Vlad the Impaler, voivode of Wallachia (not Transylvania, a neighboring province)—is alive. Or, rather, he has existed in an undead state as a vampire since his beheading by the Ottoman Turks under Sultan Mehmed II (1432–1481), who conquered Constantinople in 1453, ending the Byzantine empire and offering a serious challenge to Christian hegemony in Central Europe and the Balkans. The discovery of such a book—printed by Dracula’s archivists and hidden for the explicit discovery and enticement of the world’s most promising historical minds over the course of centuries—is repeated twice in the novel: first by Rossi in the 1930s and then by Paul in the 1950s, and we get three other stories (told by Turgut Bora, Hugh James, and Anton Stoichev) about their own such discoveries. Repetitions and returns, history echoing across centuries, quite literally haunting the present, and embodied threateningly if vaguely in the opening address of Rossi’s initial letters—“My dear and unfortunate successor”—, is a classic convention of the Gothic novel.

The Historian unfolds across three parts, each with an epigraph quoting from Dracula, and the bulk of the actual narrative takes place in Paul and Helen’s timeline in the 1950s. The first part focuses largely on Narrator learning about her father’s own discovery of a book (the one she found in his library) while studying for his PhD in history on seventeenth-century Dutch merchants at an elite university (almost certainly Harvard). When Paul brings the book to his dissertation advisor, Rossi, the older man reveals his own similar book and hands over his research into it, including letters that describe how he got scared off further research when he was confronted in a Turkish archive by a man with fang marks on his neck, and how he came to believe Dracula was alive after his friend Hedges was killed on Rossi’s doorstep in Oxford. Rossi disappears, leaving only a smear of blood on the ceiling, just after handing over his notes to Paul. Shortly after, Paul meets Helen, a mysterious, severe-looking Hungarian-Romanian anthropology PhD student who is reading Dracula, and who it turns out is Rossi’s daughter. She was conceived when Rossi pursued his Dracula research into Romania in the 1930s—but, curiously, Rossi’s letters don’t mention such a trip and when Helen’s mother wrote to Rossi, he assured her he had never met her. After Paul and Helen are attacked by a vampire librarian, who is jealous that Dracula has taken Rossi to his tomb instead of him, and who bites Helen for the first time, the two PhD students embark on an international adventure to find the real location of Dracula’s burial—not at Lake Snagov, in Wallachia, as traditionally believed—and rescue Rossi.

Most of this story is told in bits and pieces to Narrator by Paul as they travel to various Mediterranean towns, like Ljubljana and Venice, and assorted mountain retreats, such as the Saint-Matthieu monastery in the Pyrenees, following the itinerary of Paul’s work in the 1970s as head of an Amsterdam-based diplomatic NGO brokering peace between the East Bloc and the West. Kostova lingers on scenes in these ancient cities in a manner that speaks to memories of her own youthful travels in Europe, so that the restaurants and cafes and tourist attractions, as well as the logistics and frustrations, the romance and leisure of such experiences, are brought to vivid life. This, for her, is the Victorian emphasis on setting that she so praises—and which is not, of course, actually specific to nor definitive of the British Victorian novel. Still, Kostova wonderfully, achingly conjures a time and place and set of life circumstances (yeah, the vampires included) that a much younger me could not help but want to experience myself. The life of Paul and Narrator, easing by train from one beautiful, eternal city to another, and engaged the whole time in a deeply loving father-child relationship, albeit one tinged with yet unexplored traumas, seemed so ridiculously distant to me and at the same time so enviously desirable that I could not help but fall in love with the dream of privilege, class, and ease of life on display in the first part of The Historian. Setting the pull of Dracula and Kostova’s fantasies of academia aside, I suspect the sophisticated life of a perpetual traveler in Europe was also a major draw for American readers, going as it did beyond the tourist traps of Paris and Rome highlighted so prominently in Brown’s The Da Vinci Code. I’ll discuss Kostova’s fantasies of academia and historical context in greater detail below, but I wanted to highlight in this reflection on the narrative just how powerful and affecting they were for me at one point in time.

Part two follows Paul and Helen’s journey to Europe, starting first in Istanbul and then following obscure leads next to Hungary then finally to Bulgaria. In the present (1970s), Paul has disappeared while he and Narrator are on a trip to Oxford. In his wake, Paul leaves behind a manuscript detailing his trip to Europe in the 1950s, and its aftermath, as well as an ominous note about going to look for Narrator’s mother, Helen, whom he now believes is alive. Rather than remaining at home in Amsterdam for her father to return, Narrator slips her housekeeper’s leash and sneaks off to what she imagines is her father’s destination: Saint-Matthieu in the Pyrenees. A young Oxford lad named Barley, sent to accompany her back to Amsterdam, gallantly accompanies her to ensure her safety—his don, Hugh James, another Dracula book recipient, wouldn’t like Paul’s daughter getting hurt.

The train trip from Amsterdam to Perpignan is intercut with lengthy sections from Paul’s manuscript. In this mediated memory of the past, Paul and Helen search for the archive of Mehmed II visited by Rossi decades earlier, which might contain a clue to Dracula’s real tomb, and after a failed attempt to locate the archive they happen across a Turkish professor of Shakespeare, Turgut Bora, who overhears them in a cafe and reveals that he, too, received a book. It turns out that Turgut is not only just as obsessed with learning about Dracula but he is also a member of a secret order of janissaries established by Mehmed II in the fifteenth century to fight Dracula across time and space and even beyond death. (This details is revealed later and it is very silly; it doesn’t explain Turgut meeting them—that was truly happenstance—and it doesn’t make much historical sense, nor does it ever come up again or even impact the narrative, so I imagine it was added at the suggestion of editors to make the narrative just a tad more Brownian.) We learn increasingly about Vlad Țepeș’s historical fight against the Ottomans, how the Ottomans likely taught Dracula a measure of their cruelty and torture techniques, and how Vlad became both a military annoyance and a theological challenge to the Ottomans and Islam, as much as to nearby Catholic kings, such as Hungary’s Matthias Corvinus.

After further encounters with the vampire librarian and the discovery of documents hinting at some Wallachian monks travelling to Istanbul the year of Dracula’s death (1477), bringing “plague” with them, Paul and Helen jet off to communist Hungary—with help from Helen’s communist apparatchik aunt—to learn what they can about Rossi’s mysterious visit to Romania in the 1930s from Helen’s mother. Paul and Helen attend an academic conference as cover for their visit, are investigated by the communist secret police (ÁVH), meet Hugh James (another Dracula researcher), discover a few archival hints about those Wallachian monks, learn the story of Rossi’s courtship of Helen’s mother, and get a packet of letters Rossi accidentally left behind when he visited Transylvania. The letters reveal that Rossi met an archaeologist at Snagov who outlined the physical evidence proving Dracula was not buried here; he also visited “Dracula’s castle,” had an encounter with a wolf (Dracula), and witnessed the Romanian fascist Iron Guard celebrating in the shadow of the castle (Dracula looking on with pride). Helen and Paul determine from an obscure comment in an earlier letter that Rossi was hypnotized by Dracula on his return to Greece, some days later, to forget about his trip to Romania. The letters also reveal that Helen, in addition to being Rossi’s daughter, is also descended distantly from Dracula himself! (This isn’t really relevant, it’s more of a “gasp! egads!” insertion to feint at tragic depth, without affecting the story in any way.) The Hungary trip, however, turns up very little for Paul and Helen’s research, but thankfully Turgut calls and announces that another recently discovered archival document suggests that the Wallachian monks they are tracking went to Bulgaria—and so into communist Bulgaria they must go!

Where the first part of The Historian deftly interwove Narrator’s present with her father’s recollections and with Rossi’s letters, and emphasized the emotional toll it took on Paul to tell the story of this painful past, part two dispenses with this structure—where the narration of the past naturally and logically intercuts the present, since the narration of Paul’s memories is itself part of the 1970s present—and instead more clumsily inserts large chunks of Paul’s written narrative of the 1950s into Narrator and Barley’s rather boring train journey. Very little happens in Narrator’s timeline, with the exception of a moment when Narrator wakes up on the train alone, except for a man shrouded by a newspaper, who asks where her father has gone, and who is very clearly Dracula, forcing Barley and Narrator to hop off the train to escape their pursuer, only to take another train the very next day (ah, the predictability of European train travel—and, apparently, the inability of Dracula to get off a moving train and track down to young adults!). This clumsy mixing of timelines continues into part three, right up to the climax at Saint-Matthieu, and does very little for Narrator as a character. The only semi-interesting part of the 1970s narrative is her and Barley’s relationship, which even then feels forced for the sake of yet further Gothic repetitions: they have an awkward pseudo-sexual encounter that mirrors Paul and Helen’s own blossoming romance as lovers brought together by the threat of Dracula while in pursuit of a missing father who has left behind only vague clues of his own past encounters with the vampire.

Part three continues the narration structure of part two, with Narrator and Barley in the present locomotively winding their way toward the Pyrenees and harvesting the first fruits of young love, and Paul and Helen in the 1950s heading into Bulgaria on their own dangerous journey. Part three is much faster paced than the previous sections, in large part because by the time they get to Bulgaria, Paul and Helen have collected a number of hints and clues about Dracula’s death and burial, culled from archival documents, literary accounts, monastic correspondence, folk songs, and maps—and these clues each provide tiny hints at the larger picture which rapidly comes into focus with information discovered in Bulgaria. Turgut and his secret janissary order find a single clue that suggests the late-fifteenth-century Wallachian monks traveled into Bulgaria after leaving Istanbul, and that they had been in Istanbul looking for something (Dracula’s head, we learn). Turgut suggests they foray into Bulgaria despite having no clear destination or other leads, and that they visit a major scholar of the medieval Balkans, Anton Stoichev, who might be able to tell them about medieval pilgrimage routes into Bulgaria and monastery interactions across Ottoman-occupied Christian lands. Helen’s communist aunt arranges the whole thing and Paul and Helen are soon in Bulgaria with a government attaché—Ranov—guiding, translating for, and surveilling them.

In Bulgaria, Paul and Helen are taken to Stoichev, who reveals that he, too, received a book and that he published an article on and translation of an early-sixteenth-century chronicle, recorded by a monk at Athos, giving a personal account of the Wallachian monks’ journey from Snagov to Istanbul to a now-lost monastery in Bulgaria called Sveti Georgi (i.e. Saint George, the dragon-slayer). This article and translation were published in the 1930s in a German-language history journal, not in an obscure Bulgarian-language journal, so it’s very much unclear how, for example, Hugh James, the novel’s only real expert on fifteenth/sixteenth century Central Europe and a professor at Oxford, never came across this article—of course, if he had, then a good 60% of this novel would be pointless. Kostova includes the entire article and chronicle in the book (474–484) and it is a good approximation of early-twentieth-century academic writing. The chronicle itself recounts the harrowing experience of Dracula’s first burial in Snagov, when he rises in the form of either a wolf or mist—or both—and terrifies the monks, whose abbot ultimately elects to send the body to Bulgaria, with monks recovering a “relic” from Istanbul on the way (Dracula’s head). With 90% of the mystery of Dracula’s final resting place solved, Paul and Helen are sent by Stoichev to seek the lost monastery of Sveti Georgi in the library of Rila Monastery—where Helen is bitten a second time—and from there they venture across the mountains to a village that Paul (or perhaps Narrator, editing these documents decades later) labels Dimovo, to hide its real identity. There, with a folk song about a dragon drying up a river as their guide, Paul and Helen discover Sveti Georgi in the basement of a later, eighteenth-century monastery, and so find Rossi and Dracula’s final resting place.

Rossi is still alive, but a vampire now, and he very rapidly makes amends with the daughter he’s never met before Paul and Helen mercy-stake him. Rossi left behind a diary detailing his experience being brought to Sveti Georgi by Dracula, who shares his massive library of manuscripts, many lost to the rest of the world, with Rossi and invites Rossi to catalog the library. In Rossi, Dracula has found a man possessed of great historical knowledge, excellent research skills, and the proper range of language skills (although, not Ottoman Turkish or Arabic, which comprises an important chunk of Dracula’s collection…) to handle his collection and catalogue it appropriately in anticipation of its move to a new lair closer to the major capitals of Europe. Moreover, of all the people Dracula has handed out the mysterious books to, and whom he has subsequently warned off, Rossi was the only one to defy Dracula’s warnings twice. Dracula has apparently spent centuries enticing scholars to find his tomb and then scaring them off by killing their loved ones, all to ensure that whoever does find his tomb is the right kind of morbid and morally compromised. (As Rossi points out, he didn’t actually find his tomb, but was kidnapped.) Rossi is offered the chance to join Dracula as a vampire, but refuses. Dracula makes him a vampire anyway.

Rossi’s diary of his days in Dracula’s captivity, which occupies a mere 23 pages of the 642-page novel (566–589), are the only direct experience we have of Dracula. Yes, there are various instances when he is glimpsed from afar—as Helen later confirms, when she says that Dracula was stalking Paul and Narrator across Europe in the first part of the novel; or when Rossi sees a man watching the Iron Guard with pride; or when Narrator meets him on the train—but only here does Dracula speak for himself and do anything more than menace at a distance. This is, perhaps, an attempt to make Dracula mysterious and therefore unknowable, to transform him into a villain who could strike at any moment, from anywhere. And no doubt in presenting Dracula this way, Kostova intended him as an allegory for the similarly shady figures of the communist governments of Hungary and Bulgaria who strike from the shadows and hamper Paul and Helen’s efforts to track Dracula down. In the most generous reading of the novel’s formal contrivances, we can say that The Historian layers knowledge and information in ways that distance that knowledge from our/Narrator’s present while also emphasizing the imbrication of past and present so that the present is inextricable from the past—in fact, the past acts on the present in very clear, even deadly, ways. When we “meet” Dracula through Rossi’s diary, we meet him filtered through Rossi’s memory, filtered through Paul’s memory, filtered through Narrator’s memory and her editing of her father’s written narrative: Dracula is thrice mediated, thrice distanced, and we are thrice reminded that his presence pervades those decades and those layerings of mediation/distancing to reach us nonetheless.

From Rossi’s diary we learn that Dracula’s motivation, his driving reason for becoming a vampire and creating this massive library that catalogs the world’s evils, is in service of perfecting evil in the world. Dracula saw himself in life as a victim of the horrible evil done when the Ottomans conquered Constantinople and he calls 1453 the evilest year in history. Dracula says, pettily and tritely, of his motivation: “I vowed to make history, not to be its victim” (584). We learn from Dracula, and later from Helen’s research, that he has carefully traced the violence of humanity in the preceding centuries and been awed by it, especially by the atomic bombs (curiously, though Dracula has a copy of Mein Kampf, he never mentions the Holocaust—which you might expect would be the apex of the necropolitics he adulates).

Through Dracula, Kostova suggests that The Historian is ultimately about the violence of history and of the twentieth century in particular—a topic I’ll explore more below. Dracula’s theory of history is “that the nature of man is evil, sublimely so. Good is not perfectible, but evil is” (586). And so Dracula wants to perfect evil by… well, it’s not clear how, exactly. But I suppose by leaving books for historians to find, spooking them so they don’t actually discover his tomb, and smiling from a distance, in the dark, as Romanian fascists cavort in the woods? Dracula is never revealed or even intimated to have had a hand in the awful events of the past, just to have been there, to have witnessed them, smiled on, and collected documentation, which he reads at night in his armchair in his tomb under an ancient monastery in a forgotten valley in a tiny village where “[a]pparently this century was not occurring” (541). Spooky.

From these disappointing revelations of Dracula’s utterly mundane and pretty uninteresting theory of history and of evil, the novel trips toward its conclusion. With Rossi dead, and Dracula fled from his Bulgarian tomb before Paul and Helen could stake him, too, Paul quickly recounts the aftermath: he and Helen returned to America, got married, finished their PhDs, had two miscarriages, eventually had Narrator, and Helen disappeared one night while they were visiting Saint-Matthieu in the Pyrenees. Here, after learning about a legend that the founding abbot rose from the dead at night (you know, vampire shit), Helen disappears. Oddly, although the narrative Paul relates of this time quite obviously suggests that Helen was either attacked or kidnapped by Dracula—there being only a single blood stain left behind, just as in Rossi’s disapperance—and although money was withdrawn from their bank account days after Helen’s disappearance, Paul decides that it must have been suicide. Given the past 600 pages, Paul’s decision to take her disappearance as suicide and to not think about it for almost 18 years is frankly unbelievable, and stupidly so. And, indeed, we later learn from Helen that it wasn’t suicide, but that she chose to leave Paul and Narrator in order to hunt Dracula.

With the story of Paul and Helen concluded, the narrative shifts to Narrator and Barley in the 1970s for the final few pages of the novel, intercut with a few awkwardly sappy postcards Helen wrote (but never sent) to Narrator after her disappearance, and which she apparently left for Paul very recently—prompting his flight from Oxford to the Pyrenees when he realized that Dracula must have moved his tomb from Sveti Georgi to Saint-Matthieu. Everything comes to a very quick and explosive climax as Paul, then Narrator and Barley, then Dracula, then Hugh James, then, finally, Helen show up at Dracula’s new tomb. Dracula kills James, Helen kills Dracula with a silver bullet, everyone is reunited and lives (except for James) happily ever after, albeit with a shadow of melancholy, until Helen dies 9 years later of “wasting illness” (634) and Paul many decades later, “killed by a land mine in Sarajevo” while on diplomatic duty (635). The novel finally wraps up with an epilogue, set in the Narrator’s adulthood in the early 2000s, as she explains the event that prompted her to write this novel—or, rather, this actual account of historical events. To repurpose Rossi’s words to Paul, recounted decades later in his story to Narrator, written down by Narrator still decades later for us: “Dracula—Vlad Țepeș—is still alive” and Narrator has received her own book. In reflecting on this traumatic continuation of the narrative, Narrator turns to the historical imaginary and she/Kostova concludes the novel by imagining Dracula conversing with the abbot of Snagov as Dracula reveals that he has found the answer to immortality and so “looks […] as if all the world is before him” (642).

Even to its admirers, the conclusion of The Historian seems to disappoint many—especially the final confrontation with Dracula. After all, Dracula, the vampire, the reason why most people will read this book, the great evil stalking the novel for 600+ pages, is dispatched in an encounter that is, at most, and generously delineating what counts as a “page,” three pages. In fact, a good deal of the last 50 pages of the novel is frankly disappointing. Here we have Dracula’s revelations of his C-list comic-book supervillain idea of evil, we have the awfully trite postcards from Helen that read like an LLM’s idea of how a mother would write to the daughter she’s never met (and which retread much of the cosmopolitanism of the first part of the novel), we have the nonsensical revelation that Paul thought Helen had committed suicide, we have the incredibly quick “death” of Dracula that reads as if Kostova is ashamed to have written herself into a situation where she absolutely has to pen an action sequence, and to top it off we have the completely unnecessary ending that imagines Dracula looking out over a valley—again, like a poorly written supervillain—and imagining all of the evil of the coming centuries as his prize.

Kostova’s ending, of course, is meant to return us to the beginning, to imagine where all of the evil behind this story started, and to gesture at how, lacking any first-hand or primary evidence, the historian falls back on her imagination. This suggests, further, that history itself is a kind of imagination, always mediated, never directly experienced, and also that the stories we tell about history are a kind of refuge from, just as much as they are a reckoning with, the present. But, like much of the novel, this final imaginary of Dracula is hollow and atmosphereless, it offers no sense of Dracula, no deeper exploration, and reads in the end like the novelization of a film scene. Flat, secondary, boring.

Flatness, I think, characterizes much of The Historian. Kostova’s language is finely wrought at times, and her descriptions are certainly masterful. As I said, she conjures the world Narrator experiences with a deftness that suggests personal experience. But on reflection, and having read this book now six times, I find a stultifying sameness to her descriptions. Ljubljana might as well be Budapest or Sofia, the Dolomites are no different to the Pyrenees or the Rila mountains. The descriptions are all wonderfully evocative of something—but a same sort of something, a beautifully rendered fantasy of Europe that recycles textures and ideas and commentary (e.g. of the crossroads of history, of East meeting West) to bring the world to copy-paste life. For this reason, it took me several readings to realize that Paul’s early narrative is set in America, not Oxford, because there’s seemingly no difference to the academic world Kostova conjures in both Rossi and Paul’s timelines.

But worst of all is the sameness and flatness and grotesque emotionlessness of Kostova’s narrators. We have Rossi, Paul, Helen, Brother Kiril, Stefan of Zographou, and of course Narrator herself, and they might as well all be the same person, for they write with the same style and language and tone, despite the decades and centuries and cultural contexts separating them. If Kostova has mastered the craft of a well-wrought sentence, her lessons appear not to have included discussion of tone, voice, affect, or atmosphere. Moreover, it’s a huge feat for Kostova to write a younger woman—or, at least, an adult woman recalling herself at that age—who reads as if written by a man, who seems to be processing the experiences of women, of having her first period, of being “not like other girls,” as though second-hand, heard from a sister or gleaned from pointed questions to a girlfriend.

It might be tempting to ascribe Kostova’s drab, flat, detached style to her craft, that is, to read it as a purposeful choice: as evidence that the narrative is gesturing toward its own circumstances of production. That is, perhaps the sameness is an indication that the novel is put together by one person, that everything is filtered through Narrator’s own voice—and that that voice, coming from someone who has just been given her own book by Dracula, when she thought him long dead, is processing these earlier narratives and memories through trauma, grief, shock, etc. That’s a potentially interesting reading, but a thin one. After all, Narrator—like Stoker—tells us up front that she has presented the texts exactly as she has received them, and the letters, archival documents, and her father’s written narrative are all offered as quotations (with each paragraph beginning accordingly, and quotations within using single rather than double quotes, per American style guides for quotation). It’s hard, then, to rationalize the sameness of style and tone as a purposeful choice; it seems, rather, to be how Kostova writes. I see this reflected in the fact that Kostova has no eye for atmosphere. Words like “terror” and “horror” abound—the former 104 times and latter as many as 50 (accounting for morphemic variation, e.g. terrible, horrifying, etc.)—but their affects are always absent. Ostensibly a Gothic novel, or at least strongly inspired by two novels that are indisputably Gothic, there is hardly anything Gothic in the novel; instead, there are the scenery and literary forms, lacking the substance or feeling, of the mode.

On rereading this novel for the sixth time, six years since my previous read, at which point my earlier unflinching love for the book had begun to fade, I could not help but be endlessly frustrated by The Historian—page after page. In the next section, I turn to an extended exploration of why I think this is by looking more closely at the context of the novel’s literary production and its politics, namely in how The Historian presents history and violence. This is, yes, shaping up to be one of my longer essays, but it feels warranted given how deeply this novel once moved me. I also, now, have more tools to explore this novel critically. If those tools kill my darling, so be it. Nothing was meant to live forever.

Kostova’s Spectres

For a certain kind of person, myself included, The Historian is a novel that flatters by appealing to readers’ fantasies of academia and of their place—their belonging, perhaps—in those fantasies. It’s the ultimate academic fantasy, confirming for the intellectually inclined that books are, in fact, dangerous and can be the gateway to a terrifying (and, let’s be honest, exciting) world. It says both “Here is dangerous” but also “You belong here,” and it always ensures that the danger is never a true threat to the reader’s belonging, since the dangers of this vision of academia are averted by the very tools and affordances academia proffers: research and language skills, time to study and learn, esoteric knowledge that sets scholars apart from the world and that also has the potential to operate on the world in real ways, and an invitation to a global community of like-minded genius eccentrics. Oh, and the aesthetics: the tweed, the books, the Gothic libraries, the will-they-won’t-they of it all—damn good stuff. These fantasies are powerful. I was once completely lost in their romance. They’re a major part of the reason I came to love this book over fifteen years ago, leading me to study languages I never would have considered and to explore histories and cultures that were once a distant curiosity.

In reading a novel, I had never felt more keenly that this was a life I could have and now desperately wanted: not only the monastic life of the mind embodied by Rossi and Paul, but also the close relationship with a parent (no matter how tragic, really, it was) found in Paul and Narrator’s connection; the ease of life unconcerned with money or the potential for success (for every narrator, it’s a given, both the academic success and the attendant material life that supports and flows from it); the facility with multiple languages; and the deep familiarity with history and with life in Europe. All of this was extraordinarily glamorous to me. The Historian offered me a vision of academia I could lean into, driven by normative ideologies and self-reinforcing fantasies of intellect, research, and the life of the mind. Ideologies and fantasies that are deeply embedded in and celebrated, unquestioningly, in The Historian. Ideologies and fantasies that continue to circulate, with renewed vigor and perhaps never as popular before, in the recent literary formation that has come to be called “dark academia.”

Dark academia might be the last aesthetic microgenre of the waning Tumblr era. The microgenre emerged on Tumblr first in the mid-2010s—one designer described it as an aesthetic response of “[t]he Harry Potter generation” to the magicless conditions of post-2008 adulthood—and exploded onto TikTok during the pandemic isolations of the early 2020s. It was initially a visual aesthetic for interior design, fashion, and online vibes freebasing, but it quickly picked up on literary antecedents, most especially Donna Tartt’s The Secret History (1992). The shift to TikTok and the cultivation of reading lists that would both give readers entry into dark academia storyworlds (i.e. through Tartt, midcentury campus novels, really anything with a Dead Poets Society feel) and offer readers something approximating the imagined curriculum of characters living in the elite academic echelons of dark academia (i.e. mostly nineteenth century classics), contributed to a wave of new fiction written explicitly as “dark academia” (or at least labelled as such by trend-chasing publishers). Like many microgenres that emerge rapidly on social media platforms and that emphasize the communal creation of a hyper-specific vibe, usually in response to an extremely delimited set of dehistoricized influences, dark academia is both incredibly specific—moody, mysterious, pseudo-Gothic, focused on elite educational institutions—and incredibly vague, subject to constant argument and disagreement about the boundaries of the microgenre, about what counts and what doesn’t (Tartt’s novel is the single universal, it seems; for a great historical overview of dark academia, its aesthetics, its permutations across social media, and critiques of it, I suggest The Book Leo’s video “‘dark academia’ has lost all meaning”).

The Historian is in many ways an ideal work of dark academia, though it rarely shows up in readers’ lists of microgenre members. It offers a vision of an academic life that is unattainable to many and seductively comforting: it’s a world of handsome gentlemen in tweed, of lectures halls and hidden library carrels at elite academic institutions, of an abiding sense of timelessness and placelessness that owes this very sense of worldly detachment to its temporal and geographic inheritances as premier institutions of empire and aristocracy, locus an ostensibly pure, unpolitical, uncomplicated life of the mind. At the same time that The Historian traffics in this deeply privileged elite imaginary, it panders to its readers: you, too, can get here, if you’re smart enough. After all, the poor girl from a communist country did. And like the most sophisticated dark academia texts, The Historian teaches readers how to belong: what is the historical method, how does one think historically, how are archival materials handled, how do we draw conclusions from disparate sources, how do we conjecture about history from the basis of literary, archaeological, and cultural sources, what languages should we learn—and, perhaps most importantly, what does it look like to have a truly curious mind? Moreover, The Historian reifies the notion of academia as an endeavor of solitude, of great minds growing in relative isolation—“alone, undisturbed, in monastic silence” (50)—punctuated by the occasional friendly argument with an equally solitudinous scholastic confrere over something as specific as trade between Utrecht and Amsterdam in the seventeenth-century Netherlands, finished with a spot of coffee from porcelain cups before returning to sweet solitude.

For some, all of this is deeply appealing. It certainly appealed to me. And, indeed, the admirers and defenders of dark academia today point to the microgenre as a democratizing force for education and knowledge production, since the microgenre encourages learning, reading, and (ostensibly) critical thinking. Yet while some texts produced in or retroactively roped into the microgenre are read as critiquing the elite spaces of the academy, maybe even dismantling its ideology of class and institutional structures (as many have claimed about R.F. Kuang’s Babel and Katabasis), dark academia is nonetheless fueled by the aestheticization of, obsession with, and emotional investment in the idea of the academy and more specifically in a very particular idea of what academia and knowledge production should ideally look, feel, and be like—one collaged together from TikTok mood boards, period pieces, and vibes. (For a great look at dark academia

The Historian challenges none of this. Indeed, its idea of academia is a committed fantasy that takes deadly seriously the practice of history as an academic field—an idea that I, and many others, celebrate. Kostova glorifies academic life, aestheticizes it as a kind of beautiful, solitary practice, but also puts academia back into the world, into the objects of its study: archives, materials, cities, places, and people. Moreover, despite being interested in vampires and the horrors of history—which is incredibly dark-academia-coded—The Historian isn’t all that horrifying. Academia, in Kostova’s rendering, is not a cutthroat world, it’s not a place of murder and jealousy, as in Tartt’s The Secret History, and Kostova’s novel doesn’t self-reflexively read academia as an institution benefitting from or reinforcing structural violence. Kostova’s academia is no Hunger Gamesian world of intellectual conflict between equally sexy, equally smart, equally predictable antagonists—a bare minimum for today’s dark academia. Rather, in her rendering, academia is a place of wonder and camaraderie, a refuge from the actually violent world, such that the political turbulence of the 1930s, 1950s, and 1970s never touches the characters’ lives. It’s only when Dracula invades their library carrels and they venture outside of the Ivory Tower that they are under threat from the “real” world.

Central to understanding how Kostova interacts with (ideas about) academia—how she simultaneously suggests criticism, while ultimately reifying the thing itself as just fine how it is—is Kostova’s presentation of how historical research works, or, better said, her narrativizing of historical research as part of the plot. This novel is, after all, called The Historian and its lessons with regard to academia are explicitly about history, as I suggested above. The narrative structure is that of a detective novel, where the clues to the mystery—where is Dracula’s tomb?—are littered throughout disparate sources written over centuries, each tantalizingly and perfectly conveying just a hint of meaning that leads to something else, each reifying the truth value of the previous clue, and all of it leading to a single, definitive, unimpeachable answer to the mystery. Perhaps the greatest fantasy of the novel’s vision of research lies here, in that fact that Dracula is tracked down through documents written across centuries in half a dozen languages, in manuscripts held in disparate libraries, coming from diverse literary and cultural traditions, surviving centuries of ownership and devastating wars, passed miraculously through unbroken chains of provenance, and often found by sheer luck when Paul and Helen happen to meet the right person who recalls an obscure details that leads them to a new manuscript or map or memory, the relevance of which is always initially circumspect but then proven to be not only relevant but absolutely crucial to the whole. Helen’s warning to Paul about “notoriously slippery” folks songs is the perfect example of how the novel simultaneously presents the skepticism of a good researcher while delivering impossible transhistorical surety, because in the end, the two folk songs they find prove to be exactly, even hyper-specifically about the obscure thing they’re researching (537).

The Historian offers up the most wonderful fantasy of what it’s like to do historical research, and it creates a tempting, flattering vision of the brilliance and luck and superhuman skill required to compete in academia. The novel’s fantastical logic of research suggests the collusion of history itself to make all the puzzle pieces fit, or at least the manipulation of everything by Dracula himself, as part of the game he has played over the centuries to entice (and threaten) scholars who get close to figuring out where his secret evil lair is (muahaha!). And the research is also a matter of life and death, adding further fuel to the fire of academia’s self-importance. This is the ideology of academia and of knowledge-production at work in The Historian.

Ultimately, although Kostova’s novel is much smarter and better written than Dan Brown’s novels, it’s really not hard to see the comparison between the two that was so heavily highlighted in initial reviews of The Historian. After all, the discoveries of Paul and Helen—and their ragtag lot of co-investigators bound by the shared curse of Dracula’s books—obtain through the same ridiculous connecting of dots, follow just as convoluted a research journey, and come to equally episteme-shattering conclusions as those of Brown’s symbologist Robert Langdon. And while Paul and Helen’s path doesn’t lead to the discovery of Christ’s mortal line of descendants, with all signs pointing in no uncertain terms to the male lead’s romantic interest being Jesus’s last surviving great-great-etc. granddaughter, Paul and Helen’s equally implausible albeit slightly less tenuous chain of historical evidence does lead them to an undead vampire warlord and reveals Helen is his descendant. Not to mention the ridiculous presence of a secret, 500-year-old organization fighting (ineffectively) against Dracula’s evil. The Historian is The Da Vinci Code for readers whose educational and class aspirations make them at least a little embarrassed to have Brown’s book on their nightstand.

This latter point is crucial to placing The Historian in its critical and historical context. While the dark academia discussion is certainly interesting, and retroactively situates why a 642-page novel about archival research was so very interesting to millions of readers, the spectre haunting The Historian and everything it’s doing is the program era, Mark McGurl’s term, described in a book of the same name, for the literary-historical era and sociocultural formation of writing produced under the auspices of creative writing MFA programs. The Guardian noted that “Kostova is elevating the pursuit of non-commercial fiction to the point of principle,” juxtaposing this claim with Kostova’s own statement that she was writing deliberately slow fiction, something meant to be read in more than just “an hour.” Kostova was, in her mind, the bestselling anti-bestseller: a rebel taking us back to “slow” Victorian fiction, not adventure-choked, hIgH oCtAnE airport novels. Quite obviously, though, The Historian was a product of the MFA programs developed in the United States in the postwar period—and in this regard, the novel is anything but unique, even in its pretensions to be a bestselling anti-bestseller or to make genre fiction respectable and literary.

McGurl’s conception of the program era, and more specifically of the shared qualities common to most program fiction, especially the emphasis on craft—i.e. the sentence and its aesthetic quality as the main artistic feature of the fiction—, on “write what you know,” on “finding your voice,” and on what I read as a depoliticized hyper-individualism, are expounded in McGurl’s nearly 500-page masterwork (which prompted a number of books by other scholars in response, e.g. Eric Bennett’s excellent Workshops of Empire). I agree with McGurl’s overall argument and the historicization of program fiction, but some of his readings of individual authors and novels are, shall we say, idiosyncratic and perhaps overly generous to program fiction as a literary formation. I much prefer Elif Batuman’s take on program fiction, in her hilarious and occasionally problematic review of McGurl’s book:

the quality I find most exasperating about programme writing […]: oversophistication combined with an air of autodidacticism, creating the impression of some hyperliterate author who has been tragically and systematically deprived of access to the masterpieces of Western literature, or any other sustained literary tradition.

Of course, any broad condemnation of a body of fiction is always at least partly unfair—something I know about as a critic of mass market genre fiction. But Batuman’s critique of program fiction is a compelling one, and one I’ve written about, if somewhat harshly, elsewhere.

Kostova’s The Historian embodies many hallmarks of program fiction. It is distinctly craft focused: the sentences are, generally, beautiful. Kostova has mastered her “voice,” albeit to such an extent that all of her characters speak with the same flat, detached, hyper-educated voice (with the exception of Turgut, whose English is butchered—offensively, I think—for character-giving effect). Kostova clearly writes what she knows, as I’ve explored in depth above. And Kostova gives off the sense of being deeply familiar with Stoker’s Dracula, of being, as Batuman puts it, “hyperliterate” while at the same time seemingly unable to integrate what she has learned from her wide reading into the novel itself. The complex social, sexual, gender, racial, and imperial politics of Dracula, which have provoked decades of fiercely debated scholarship, and which is the primary literary ancestor of Kostova’s novel, its clearest and most powerful intertext, are absolutely voided in The Historian, which offers no interesting politics, merely observes things with a wry distance, and has, ultimately, no teeth. Kostova cannot even bear to write a proper confrontation with Dracula to end the novel, and instead hides him in layers of temporal and material mediation, deep in Rossi’s diary, and even there all she gives us is a mustachioed, velvet-wearing, book-loving doofus who wants to “perfect evil.” It’s trite, flat, boring. Echoing the worst impulses of program fiction’s insistence on being Not Genre, The Historian is afraid to be a vampire novel.

The fear of being a vampire novel, and of being political in the way many vampire novels have been, even before Stoker’s Dracula, echoes the novel’s failures to do anything with what could be interesting critical reflections on academia. In one of my early rereadings of The Historian, I highlighted just one passage in the novel and marked it, ostentatiously, with a sticky note, as if to remind myself that this was the takeaway of the novel:

A week ago I’d been a normal American graduate student, content in my discontent with my work, enjoying deep down a sense of the prosperity and moral high ground of my culture even while I pretended to question it and everything else. The Cold War was real to me now, in the person of Helen and her disillusioned stance, and an older cold war made itself felt in my veins. (206)

This passage is from Paul’s narrative about his and Helen’s adventures in the 1950s, reflecting on how much his life had changed and how quickly, while walking the streets of Istanbul. It’s the sort of vaguely self-critical reflection that anyone with a fragile ego can accept, because it suggests a critique—namely, that academics in rich Western nations at elite institutions have a sense of moral superiority because they can safely criticize the things they disagree without fear of repercussion—without having to make one. Kostova’s gestures at critique, but failure to pursue the crucial impulse is frustratingly endemic to The Historian. Critique is an impression the novel gives, not an actual function of the text. And this extends to what I think Kostova is most interested in, what her novel is “about”: history, violence, and evil.

Shortly after Paul’s reflection above, he and Helen come across some older men preparing to play chess in a park:

[T]he two men were just setting up their pieces on a worn-looking wooden board. Black was arrayed against ivory, pawns faced on another in battle formation—the same arrangement of war the world over, I mused, stopping to watch. (207)

Before leaving the players behind, Paul “wonder[s] how long their game would take […] and which of them would win this time” (207, emphasis mine). Paul’s commentary, coming just after his supposedly self-critical reflection on his own smug positionality as a Western academic, encapsulates what seems to be Kostova’s primary argument about history and violence in The Historian. Namely, that war is a simple, if not inevitable thing, reducible in its complexity to two teams arrayed in “the same arrangement” time and again, with one side winning now, the other side later, and so on. War or, rather, a conflict between two sides is understood in The Historian as the primary driver of violence in human history, while structural forms of violence—for example, the exploitation of the laboring classes, racial slavery, settler-colonialism, patriarchy—are never even suggested.

War, and violence, in other words, are not political or even really politicizable in The Historian. They are evil, yes, but they are presented—both by Dracula and by the historians themselves who, like Paul, merely “muse” about the larger meaning of what they study—as inevitable outcomes of human interaction. To this end, the communists of the novel, whether in Hungary or Bulgaria or the Soviets themselves, whom Helen refers to as “impalers” (128), are not political so much as evil. The Historian is therefore a Cold War historical thriller with absolutely no sense of or investment in the politics of the Cold War. It presents a decidedly ahistorical and explicitly apolitical account of the 1950s—to say nothing of the other time periods. I mean, come on: in the 1970s, Paul is a diplomat yet the many prominent sociocultural and political crises haunt the periphery, unspoken with the exception of a passing reference to a newspaper—held by Dracula—with headlines about “[t]errible things […] happening in Cambodia, in Algeria, in places [Narrator] had never heard of” (234). That’s the extent of the politics this novel offers: war’s bad, huh? Terrible things happen, somewhere, exotically, far away. We are left only with musings, never with any conviction, any sense of the politics of war or of violence—of the political textures and contexts of history. In The Historian, history is just happenings, and some of them are “bad,” and the interplay between the good and the bad are inevitable.

Kostova’s understanding of history, which pretends to something like depth and familiarity with history itself and its research practices, recalls instead the West’s smug reaction to the violence, civil wars, and genocides of the 1990s, when conflicts in Eastern Europe and Africa were written off as the inevitable outcomes of ancient tribal tensions. Kostova does this explicitly when Narrator describes her father dying in Sarajevo during the Bosnian War (1992-1995), “working to mediate Europe’s worst conflagration in decades” (635). It’s an apolitical gloss lacking any sense of the injustice or genocide of that war, rendering “Sarajevo” a blank stand in for a sad “conflagration” that happened, as such conflicts inevitably do. When, in reality, the violence in Bosnia, Rwanda, Chechnya, Kosovo, and elsewhere were historical in precisely the way that they were political, and vice versa. This point is made forcefully by Noel Malcom in both Bosnia: A Short History (1994) and Kosovo: A Short History (1998), which exist largely to dismantle the idea of conflict in those two nations as apolitical, ahistorical, almost mythic wars between tribes or ethnicities. In real history, there is not “the same arrangement of war the world over,” but a morass of specific and contextual complexities that lead to war.

The Historian rejects historical complexity and rushes to quick comparisons and oversimplification in its efforts to understand history the way Kostova thinks Dracula might, and to assure—or, perhaps, warn—us that no matter how modern we are, things haven’t really changed since Dracula was beheaded in the winter of 1476–1477. In an interview with The Guardian, explaining the rise of historical thrillers like The Da Vinci Code and her own novel, Kostova argues that,

We have experienced intense globalisation the last 10 years and we are aware as never before of history as a whole and of our place in it. We are aware of the world as a small and fragile place. I also think this is an age of great anxiety. The more I studied the middle ages for this book the more I thought we hadn’t come that far in some ways.

This is a kind of vulgar medievalism, one that explains Paul’s smug musings on war and conflict as a kind of eternal chess match between a pre-political binary of good and evil. At the same time, and in the context of the novel’s overwhelming framing of violence as coming from the East and invading the West—from Dracula, reaching out to the ivory towers of Britain and American, and seeking to establish a foothold at Saint-Matthieu near the modern capitals of Western Europe; and before him, from the Ottomans who taught Dracula his cruelty and torture techniques; and after him, from the rise of communist “impalers” in Eastern Europe—Kostova’s vulgar medievalism presents history as an eternal conflict between East and West.

And that vulgar medievalism often turns to the East, to the Ottomans or Byzantines and of course to Vlad Țepeș, as the source of violence. This is contrasted in several ways to Paul’s area of study: seventeenth-century Dutch merchants, a topic Paul eventually realizes might actually be “a rather bland endeavor” (203), since Dutch merchants don’t prowl history as vampires or impale their enemies. In short, early modern Dutch merchants are boring, Kostova suggests, because they aren’t violent. But, of course, Dutch merchants’ financial success in the period Paul studies, and the financial success of the tiny nation of the Netherlands, was made possible not only through the capitalist exploitation of workers in an emerging global economy partly developed by enterprises like the violent Dutch East and West India Companies but also through the attendant settler-colonial expansion of the Dutch empire into South and Southeast Asia, Africa, and the Americas. To imagine seventeenth century Dutch merchants as unconnected to systems of grotesque violence—including participation in slavery, accounting for roughly five percent of the trans-Atlantic slave trade—is absurd! But The Historian does not think about violence systemically and it certainly doesn’t think about violence politically—at least not in the West, not among the people who produced Vermeer or Rembrandt, who went bonkers speculating on something as quaint as the value of tulip bulbs.

Kostova instead locates violence in the East. And though The Historian resists the full measure of explicit Islamophobia, it ends up being hardly different in its conservative outlay of an East/West conflict to, say, Dracula Untold (2014), a film that revels in the slaughtering of Ottoman Turks by the thousands and which has been read as an allegory for the War on Terror. Fittingly, by the end of The Historian, the violence of the East, and the eternal, medieval conflict between East and West, reaches America’s post-9/11 present: just after Dracula gives Narrator her own book in the present, the epilogue quietly references a (not-real-in-our-world) terrorist attack in Philadelphia. This suggests that the terror attacks of 9/11, and which hit Europe, the Middle East, and Africa throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, have continued in the US into the novel’s present. Dracula survived Helen’s silver bullet and has come to America, his arrival announced by a new kind of violence—Islamic fundamentalist terrorism—that Kostova sees as evidence of our eternally medieval present.

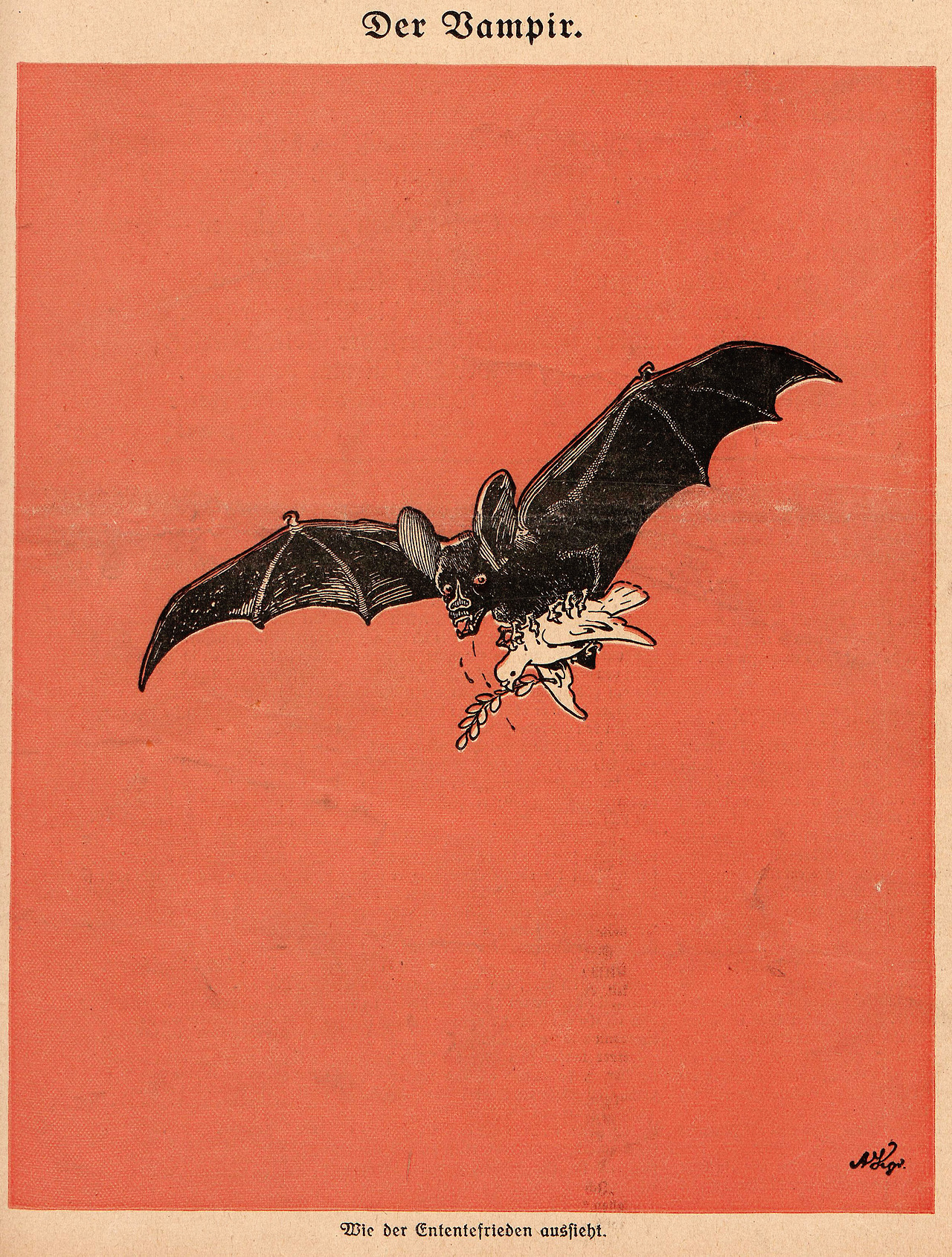

Dracula’s transhistorical persistence, his undying evil, narrativizes Kostova’s vulgar medievalism. The vampire in The Historian is a tool for thinking about evil in and through history, connecting past and present and offering a window into the evil nature of humanity—an ideology voiced by Dracula and never challenged by the novel, merely side-stepped by Rossi’s rejection of Dracula’s immortal job offer. But, as I noted above, Kostova’s interest in the vampire and the rich tradition of the vampire novel—and one doesn’t have to look far for great exemplars of politically rich vampire fiction: Anne Rice, Fred Saberhagen, Chelsea Quinn Yarbro, Kim Newman, Suzy McKee Charnas, to name a few of my late-twentieth-century faves—is almost nonexistent, except as an overwrought vehicle for her trite, disappointing, even conservative ideas of history, violence, and evil. There’s a deeper understanding of history, injustice, violence, empire, and the figure of the vampire in two very different political cartoons—Arthur Krüger’s socialist outcry against the Treaty of Versailles in “Der Vampir” (1919) and Alex Ross’s liberal criticism of George Bush in the cover illustration for Rick Perlstein’s “It’s Mourning in America” (2004)—than in the entirety of Kostova’s massive novel.

Left: Arthur Krüger, “Der Vampir” (1919). Right: Alex Ross, “It’s Mourning in America” (2004).

Parting Thoughts

Back to the beginning, back to books. I’ve come to think of The Historian in the simplest and most generous gloss as a 642-page novel expounding Rupert Giles’s defense of the materiality of books to technopagan queen Jenny Calendar (RIP) in the Buffy episode “I Robot… You, Jane”:

Calendar: Honestly, what is it about [computers] that bothers you so much?

Giles: The smell.

Calendar: Computers don’t smell, Rupert.

Giles: I know. Smell is the most powerful trigger to the memory there is. A certain flower or a whiff of smoke can bring up experiences long forgotten. Books smell. Musty and rich. The knowledge gained from the computer is a— it has no texture, no context. It’s there and then it’s gone. If it’s to last, then the getting of knowledge should be tangible. It should be smelly.

Like zaddy Giles, The Historian is deeply invested in books, in material knowledge, and in the senses of things—at least the visual, tactile, and olfactory, the descriptions of which account for a significant amount of the novel. Or, rather, Kostova is deeply invested in the idea of these things. After all, the novel’s great revelation is that Dracula is a book guy (another book zaddy?!). What Kostova does with this shocking revelation, though, is nothing. Absolutely fuck all. Sure, Dracula has amassed a great library documenting the atrocities of humanity, but beyond this mere fact, this surface idea of a vampire collecting dark books over centuries, Kostova has so depressingly little to say in all these pages about books, about knowledge, or about the natures of history, violence, and evil.

The Historian once meant so much to me. I now understand it to be hundreds of pages of noise in the shape of a vampire novel, vaguely echoing with ideas about the nature of history and evil overheard in the hallways of a freshman’s college dorm—but it has no voice with which to transform that noise into meaning, into something with more substance, more bite, more purpose than the shadow of its own wispy pseudo-intellectualism. I see now that I was never drawn to anything but the surface of this novel: the vampires, Eastern Europe, its fantasy of academia and a life filled with multiple languages and the financial freedom to travel widely and study deeply. The characters never meant anything to me, and what the novel had to say about vampires, academia, or history never meant much either—for the novel had nothing to say about these things.

It’s fitting, then, that The Historian was a gateway to other things that taught me about what Kostova merely reflected at the novel’s surface. Returning to this novel has been an experience in disappointment, but a fascinating one. I’m thankful to this book. I’m glad to see so many people lauding it on TikTok and in other online book communities, especially in the past few years, since it has been roped into the contemporary fervor for dark academia. I hope the book is a gateway for those readers as well and I can completely understand and appreciate any reader’s love for this book. But I don’t find The Historian to be a meaningful or powerful book any more, and in fact what I see in it now frustrates me even more than it disappoints me.

To get notifications about new essays like this one sent directly to your inbox, consider subscribing to Genre Fantasies for free:

I remember the fuss about The Historian, and I definitely considered reading it, but somehow never got around to it. (I do think that along the way I picked up a used copy of the trade paperback.) It does seem a shame that she essentially seems to have disappeared after the two other novels. I trust that at the very least she is a better writer than Dan Brown!

I read A Princess of Mars a few years ago — well, quite a few, at any rate some time before the John Carter movie came out. I thought it surprisingly well done on its own terms — quite readable, and reasonably enjoyable, as long as you could suppress the racist and sexist and absurdly implausible bits! I have no difficulty understanding its popularity.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah, one of the things I’ve read is that Kostova’s second and third novels were sales letdowns after the heights of The Historian, so I wouldn’t be surprised if she just decided to sit on her piles of money and putter about doing something else. Or perhaps she’s just taking a long while to finish her fourth novel. Who knows!

As for Burroughs, yeah, I actually still quite like and admire A Princess of Mars — noting, yes, it’s racism and sexism. I think Burroughs is doing interesting things and anticipating a lot of the concerns of later sf. It’s very fine early pulp writing that nonetheless is brimming with ideas. I even found Gods of Mars to be quite fascinating, especially its lengthy engagement with how ideology operates to create reality through religion, though that one is even more racist and quite explicitly so because, of course, it’s “Black Martians” who are ideologically controlled by an evil queen (possibly a riff on Haggard) and Confederate veteran John Carter who comes to rescue them. Eventually I’ll do a critical read through of the Barsoom books.

LikeLike