The Goat Without Horns by Thomas Burnett Swann. Ballantine Books, 1971.

Table of Contents

Swann, Ballantine, and Reception Woes

Reading The Goat Without Horns

Parting Thoughts

Swann, Ballantine, and Reception Woes

The Goat Without Horns, Thomas Burnett Swann’s fifth novel and his first novel published with Ballantine Books, was the best written book to date in the author’s short but incredibly productive career. It was probably also his worst novel in all the other ways that make a novel worthwhile.

The novel appeared with Ballantine just as the publisher was beginning to develop a growing list of titles in, and an identity for, fantasy as a market genre. The Ballantine Adult Fantasy series, edited by Betty Ballantine, with Lin Carter as the linchpin “consulting editor,” was in its third year. Thanks to Carter, Ballantine was also republishing Lovecraft’s work in new mass market paperback editions, starting with The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath, which appeared in the BAF series in May 1970. Advertisements for 15 BAF novels and three non-BAF Lovecraft titles appeared in the back of The Goat Without Horns, in addition to ads for sf books by Larry Niven and Robert Silverberg. On the cover, Ballantine labeled Swann’s novel “Fantasy Adventure” and called the novel “his first full-length work in book form” (though it’s only 16 pages longer than Moondust and set in a larger font). Publishing with Ballantine was a step up in literary clout for Swann, likely afforded by his growing backlist at Ace Books, his increasing prominence in the American sff magazines, namely in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, and his becoming a Hugo finalist for the Science Fantasy novella “Where Is the Bird of Fire?” (1962) and F&SF novelette “The Manor of Roses” (1966) (in addition to several other Hugo and Mythopoeic award nominations from 1963 on).

If Swann can be said to have a novel weirder and odder than his retelling of the Fall of Jericho alongside his story of an ancient society of evil, psychic, aesthetics-obsessed fennecs in Moondust, then it has to be The Goat Without Horns. The novel is a Gothic story set on the remote (and imaginary) Caribbean island of Oleandra. The tale is filtered through the lens of Classic Hollywood in terms of its presentation of the island, its inhabitants, and the caricatured voodoo-esque goings-on that threaten the protagonists. And it is narrated by a dolphin. Yes, the chubby, depressed dolphin Gloomer is the novel’s narrator. And, I suppose, why the hell not? After all, literature should experiment with everything. Doesn’t mean the experiment will work out, of course…

The Goat Without Horns is Swann’s biggest swing and, I think, his most embarrassing miss as an author. The only contemporary reviewer I could find, Fred Patten, called The Goat Without Horns “his weakest novel to date” and concluded rather harshly, if not unfairly, that it’s “unconvincing, unexciting, and not really worth reading” (The WSFA Journal, no. 79, Nov. 1971, pp. 33–34). Swann seems to have blamed this reception on fans’ lack of familiarity with the Gothic tradition he was drawing on. In his own words, from a 1974 fanzine interview (Swann’s only known published interview):

The Goat Without Horns got some terrible reviews in the fanzines, but I’m still fond of it in a quiet way. I think Ballantine gave it the wrong kind of release. I meant it to be a Gothic fantasy which quietly made fun of the Gothic conventions by giving them little twists. For example, the narrator was a dolphin instead of a terrorized maiden. The terrorized person—that is, the victim in the old house—was a youth and not a maiden, and he had an affair with the mistress of the house, rather than a maiden having an affair with the master of the house. I wasn’t trying for a monster story, as the cover suggested, or science fiction, as Ed Ferman suggested when he serialized the book. There were all kinds of veiled literary allusions to the Gothic tradition, and the satirical Gothics like Northanger Abbey, which Mrs. [Betty] Ballantine, being English, caught at once, but most American readers didn’t. (11)

I’ll explore some of the satirical work The Goat Without Horns does (or tries to do) with the Gothic tradition, but overall the argument “they didn’t get my satire!” doesn’t work very well for this novel, which falls flat in so many other regards. It especially doesn’t work to tell a “quiet satire” when everything else in the novel is pure Hollywood melodrama, with all the subtlety of Victor Halperin’s 1932 film White Zombie. In other words, this novel is really quite racist—and not in a satirical way. Satire isolates, elevates, and/or remixes elements of narrative and storyworld in order to render them an object of critique. There is no such critique of racism or racial hierarchies or colonialism or whiteness in Swann’s novel, unlike the novel’s rather explicit rendering of gender and sexuality for critique through its light satire of Gothic narrative expectations—as Swann’s quote above suggests.

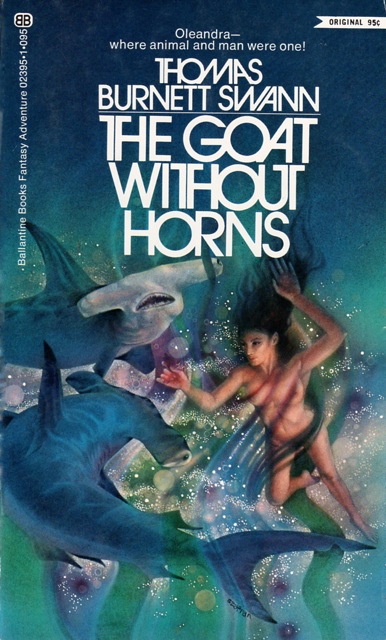

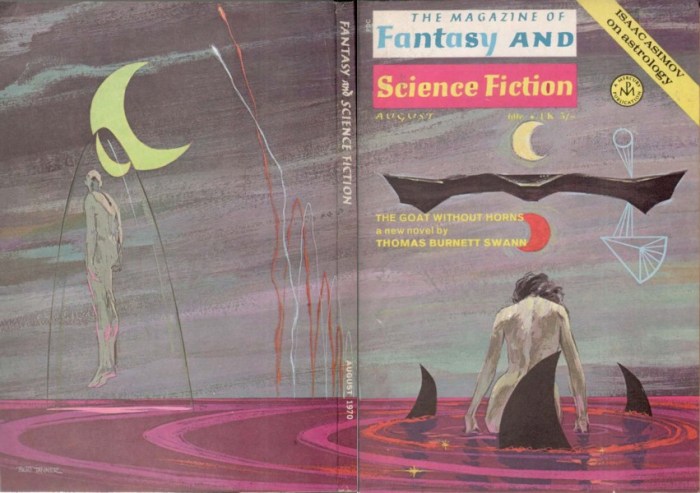

Swann’s claims that his publishers didn’t give the novel the right marketing also doesn’t feel accurate. After all, the climactic scene involves a human sacrifice to sharks, which the cover of the Ballantine paperback depicts with a wraparound painting by the renowned sff artist Gene Szafran, best known for his Heinlein covers for Signet in the early 1970s. Szafran’s Swann cover isn’t exactly impressive, but it doesn’t suggest “a monster story” any more than Swann’s own novel does. Swann also complained about Ed Ferman—the editor of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction—treating the story as sf when he serialized it in two parts (Aug. 1970, Sep. 1970), but the abstract for the first part only mentions fantasy, calling Swann “one of the field’s superior fantasists,” and quotes Swann’s own description of the novel as “monstrous at times” (4). If Swann was frustrated by Bert Tanner’s rather trippy, somewhat bewildering, but otherwise impressive cover for the August issue that led with his novel (Fig. 1), then he must not have been familiar with the magazine’s typical approach to covers (though he obviously was, since Tanner did the issue cover for his Hugo-nominated novelette). As galleries of covers for 1970, 1971, and 1972 show, F&SF often had rather abstract covers—this was kind of a thing in the late 1960s and early 1970s for sff art generally.

Whatever the contexts of The Goat Without Horns’s contemporary reception, and whatever Swann’s concerns about being misunderstood, unfortunately for him—and his readers—it’s just not a very good novel. Though, like all of Swann’s novels, it’s clearly trying to do some very interesting things and it can always be said that, hey, at least he was experimenting with form, expectations, tone, gender, sexuality, and so much more. As a result, his work still surprises more than 50 years later. It just so happens that The Goat Without Horns also bewilders.

Reading The Goat Without Horns

The Goat Without Horns is the story of Charles “Charlie” Sorley, a first-year student at Cambridge fleeing 1870s Victorian England and the grief of losing his mother and twin brother (his dad, a former civil servant of the British Raj, is long dead). Charlie takes a job tutoring the daughter of a wealthy, eccentric, invalid widow of immense beauty and unknowable age, Mrs. Elizabeth Meynell, who lives on the mostly desolate volcanic island of Oleandra in the Lesser Antilles chain in the eastern Caribbean. There, in the crater of the volcano, in a small but lush jungle, Elizabeth has built a replica of William Morris’s Red House and surrounded it with English-style cottages. The island is also home to some 30 Indigenous Caribs—who are referred to regularly by all the characters of the novel as “savage,” “barbarian,” “degenerate,” “lazy,” “indolent,” “squalid,” “slatternly,” and so many other such terms—led by the mysterious, hyper-manly Curk, who stands above the Caribs he rules as something like a deity: “to call him a Carib like his countrymen was to do him an injustice” (34). The girl Charlie has come to tutor, Jill, is a fifteen-year-old tomboy who flouts the gender conventions of Victorian society.

The novel begins with a frame narrative, typical of both Swann’s work but also of the Gothic novel since its very beginnings in the late-eighteenth century, notably with the work of Horace Walpole and Anne Radcliffe, who popularized the Gothic romance form, often with the suggestion that their novels were “real” historical accounts of events “discovered” in earlier, usually late-medieval, manuscripts. Swann’s “Publisher’s Introduction to the Second Edition” similarly positions The Goat Without Horns as a “true” story—not a novel, but a history—and beyond that it reveals that the wildly popular “first edition,” which was marketed as a Gothic romance (an incredibly popular mass market paperback genre at the time, noted for its covers featuring women fleeing houses/castles at night) was in fact an oral history passed down among dolphins and recorded by the great-great-grandson of the history’s/novel’s narrator, the dolphin Gloomer.

This fake introduction describes how scientists came to understand the dolphin language, which has “a syntax comparable to that of Japanese and a vocabulary as rich and often as confusing as Etruscan,” and which sustains a vast oral literature mostly consisting of histories (vii). The frame narrative is total Swann, offering a truly ridiculous idea with the tone of scientific and academic seriousness. Swann does this elsewhere, for example, in Day of the Minotaur, which purports to be a recent translation of the last Minotaur Eunostos’s manuscript from ancient Crete. But The Goat Without Horns is asking a lot of the reader, since the idea of a dolphin narrator is so extremely strange. And we see almost immediately that it doesn’t work.

The first chapter introduces the narrator, Gloomer, who sets the scene for taking a dolphin as narrator of an oral histories seriously. This is all well and good. I enjoy the exploration of dolphin society, which is free-spirited, polyamorous, and deeply social. It’s the same description of prehuman societies we get in all of Swann’s other novels, where the Beasts or the Weir Ones are similar to humans in many regards, but have a greater inclination toward natural kinds, are more attuned to nature and communal living, and sit outside of human conceptions of morality, of good and evil, of propriety. Often, this difference, when paired with a human entering into prehuman society (or vice versa), is a departure point for discussions of civilization, hierarchy, gender, and sex(uality). Here, however, the dolphin narrator “writes” exactly in the form of mid-century Gothic novel pastiche, widely referencing Victorian and especially pre-Raphaelite literature, and narrating in every way like a faux-Victorian man, even down to his conceptions of race, empire, and gender—that is, the very ideas a Gothic satire might be expected to critique. Swann’s efforts at satire, then, are largely at odds with his choice of narrator, such that the narrative structure that results is muddled. The novel works when the narrator is so distanced from the narration that the fact he’s a dolphin can be forgotten; when this narratological fact reasserts itself, however, the novel just becomes ridiculous. Silly is not satire.

Plot-wise, The Goat Without Horns is probably Swann’s simplest to date. Charlie goes to Oleandra, meets Gloomer, they become instant best friends (a largely one-sided relationship, since Gloomer can’t really talk to Charlie until, miraculously, he figures out how to make his blowhole “speak” English during the novel’s climax), Charlie falls madly in lust/love with the seemingly ageless Elizabeth, Jill is an absolutely weirdo who says things like birds and dolphins are evil and ugly (an inversion of Victorian aesthetic standards whereby goodness is associated with natural beauty, and which is directly related to her affinity with and affection for the otherwise despised Caribs), Curk haunts the edges of the narrative until a rather sudden climax when he pulls some highly Orientalized fake voodoo shit and offers Charlie as a human sacrifice to the Caribs’ (invented) shark-god Tark, and Gloomer charges in to save the day, rescuing Charlie and defeating Curk—who turns out to be a wereshark, descendant of an ancient prehuman people known only in the Caribbean.

The characters, the emotions, the plot, everything is somehow paper thin. The novel explodes with a string of wild revelations that make it less Gothic satire than Classic Hollywood melodrama:

- Curk is the last of the Carib kings;

- Jill is Curk’s daughter and therefore a half-Carib princess;

- Curk manipulated Elizabeth into hiring a beautiful, athletic, wise English tutor—Charlie—for Jill so that she could bear his manly half-English, half-Carib wereshark sons, whom Curk would train to lead a reborn Carib empire;

- Elizabeth appears ageless because Curk created a potion from secret Caribbean ingredients—the Fountain of Youth the Spaniards sought—in exchange for her giving him a half-English child, Jill; and

- Curk conveniently left enough of the anti-aging potion after his death for Elizabeth to continue living in her beautifullest form for decades to come

Truly, The Goat Without Horns would work as a black-and-white film starring one of Swann’s beloved darlings of the silver screen (he regularly wrote for Classic Hollywood fan magazines and dedicated several of his novels to Hollywood starlets like Stella Stevens). Thankfully, though, it was never attempted; had it been, I imagine it would have become a cult classic by virtue of its lampooning by Mystery Science Theater 3000 or the like.

Ed Patten’s review from The WSFA Journal, noted above, is worth quoting at length, since it raises a number of concerns with the novel that we can use as a launch pad for thinking about what the fuck is going on with The Goat Without Horns:

It’s hard to guess whether it’s the change in setting that’s thrown Swann off or if this was just a bad day, but this is his weakest novel to date. The descriptive narrative is lovely, but aside from a brief climax there’s virtually no action. Even the personal conflict never comes alive. Charlie becomes romantically involved with both Jill and her mother, and the plot revolves about his attempts to decide whether he really loves a woman old enough to be his mother or a girl young enough to be his kid sister?[sic.] The cultural conflict isn’t quite convincing, either. While most readers will agree that dolphins are nicer than sharks or that birds are nicer than spiders, the implication that the one is naturally good while the other is naturally evil is a bit too simplistic. But the biggest failure is in the characterization of the book’s narrator, Gloomer, the dolphin. Swann is obviously extrapolating here upon the legendary friendship of dolphins for sailors, especially young and handsome ones, but Gloomer’s feelings for Charlie are so excessive that they’re virtually homosexual. Gloomer constantly describes Charlie in terms like, “…as modest as he was lovable…’’, or, “The golden aureole of his hair was subdued by the water and clung about his ears like seaweed, but his splendor was undiminished.” Gloomer is also unconvincingly anthropomorphized. He makes statements such as, in regard to observing Charlie preparing for skinny-dipping in the lagoon, “I was not accustomed to seeing young English gentlemen remove their clothes.”,[sic.] when from all the evidence so far he shouldn’t have the slightest understanding of the concept of “English gentlemen”. The result is that the entire book, despite the quality of the style of writing, is unconvincing, unexciting, and not really worth reading. (The WSFA Journal, no. 79, Nov. 1971, pp. 33–34)

I want to echo that Swann’s writing style in The Goat Without Horns is his best yet, at least considered across the whole of the novel; he really sings in this more modern, faux-Victorian style and his prose is wonderful, though it lacks the dramatic power and emotional depth of, say, the final portion of his second novel, The Weirwoods. Patten does seem to misread a love triangle into the novel: Charlie, in fact, rejects Jill’s approaches but the novel ultimately suggests that one day they will end up together, once she has grown a full bosom (yes, really…) and learned how to be feminine by returning to England and joining Victorian society alongside her exquisitely ageless, perfectly feminine mother (who is compared to Tennyson’s Guinevere). But Patten is right that the attempted personal conflict between Charlie, Elizabeth, and Jill is flat and uninteresting.

I dissent, however, from Patten’s implied negative suggestion that Gloomer’s feelings for Charlie are “so excessive that they’re virtually homosexual.” The language is not “virtually homosexual,” it’s pretty explicitly homoerotic, using the language and tenor of Romantic, pre-Raphaelite, and late Victorian poetry—borrowing widely from Keats, Browning (Robert and Elizabeth), Byron, Morris, Tennyson, Wordsworth, Rossetti, and many others—to express the complexity, clandestinity, and aesthetic yearnings of male-male desire both then and now (there is an extended discussion of the possibly queer relationship between Tennyson and Arthur Hallam, with Tennyson’s poetic grief for Hallam held up as an ideal kind of grief). Gloomer does, in fact, express queer desire for Charlie, and Patten’s quotes are well-chosen. Gloomer explicitly sees Charlie “as an irresistible Lord Byron, whose smiles were an invitation, whose touch was a conquest” (109). And Gloomer would know. Indeed, a great deal is said about the smoothness of his dolphin skin against Charlie’s naked body underwater, where the two almost become as one.

Gloomer’s love for Charlie reflects Swann’s typical set up where a less manly, more emotionally sensitive, but wholly admirable male narrator (Gloomer) looks up to and deeply desires the emotional and physical attentions of a stronger, manlier, brotherly friend (Charlie), who is also beloved by one (or several) women. The homoeroticism of Swann’s fantasy novels, which tends to manifest as a cozy queer desire (often emotionally fulfilling, only rarely physically fulfilled), is one of the most compelling aspects of Swann’s writing and certainly shouldn’t be written off as the frightening excess Patten suggests (odd, too, coming from a guy who pioneered furry fandom). The queerness of Gloomer’s desire for Charlie is reciprocated by the latter as such a close friendship that it ultimately transcends even heterosexual love, since Charlie ends the novel by deciding not to return to England companioned by Elizabeth and Jill, but to remain alone on Oleandra to swim and live alongside Gloomer.

The queerness of The Goat Without Horns is an element of the novel’s attempted satire of the Gothic tradition. The novel inverts the gendered positionality of such novels as The Castle of Otranto or The Mysteries of Udolpho or Rebecca, casting Charlie as the ingénue whose need for escape, adventure, and romance ultimately dooms her to the machinations of the Gothic’s emplotment strategies. A youth is imperiled, not a maiden; a mistress is the object of lust, not a master. These elements were the crux of Swann’s complaint that readers didn’t “get” his novel. They are fine tweaks on the formula, but they hardly rise to the level of satire and they certainly pale in comparison to Northanger Abbey, which Swann mentions in his interview as though it’s an obscure text known only to the British—despite the fact that he names it explicitly in The Goat Without Horns alongside The Castle of Otranto, which he uses to prime reader to expect a reversal of narrative formula.

These supposedly satirical gender reversals, however, are ultimately undermined by the characters’ insistence on Victorian gender codes, with Charlie fulfilling the vision of the Byronic hero and overcoming, as it were, his feminine positionality as the “imperiled” one. Moreover, he never considers himself endangered, he is never truly threatened, and his selection as, first, the only appropriate sexual partner for Jill (to produce a new lineage of half-English, half-Carib wereshark royalty) and, second, as human sacrifice to the shark-god Tark, is precisely because he is manly, because “he had asserted his maleness, his mastery, he had overpowered” Jill and thus proved himself a worthy father for Curk’s grandchildren.

Jill, for her part, remains a tomboy who rejects Victorian feminine dress only because, in the novel’s framing, she is corrupted by the Indigenous influence of her father, Curk. With him dead, and realizing that she isn’t attractive to Charlie in her boyish dress and style, Jill looks forward to journeying to England, where she will learn to be womanly before returning to Oleandra and, she hopes, settling down with Charlie.

Elizabeth alone challenges the moral strictures of Victorian gender roles, embracing her status as a “fallen” woman, as “immoral,” for having been the lover first of Curk and then of Charlie, for abandoning the virtue of chastity. But she is also pictured as an ideal form of femininity, much like Vegoia in The Weirwoods. Indeed, Elizabeth rejects the moralized love of “hearth fires” (167), a reference to Vegoia’s theory of tamed, domestic love (the hearth fire) as a complement to—but fundamentally different from—fiery, lustful love (the campfire).

But although Swann’s gendered reversals ultimately do very little to satirize the Gothic, he goes a touch further by picking up on the psychosexual undertones of Gothic literature that have wetted psychoanalysts’ dreams since they first thought to pair Freud with Walpole, and he throws Charlie and Elizabeth into the psychosexual maze of Otranto. Elizabeth is both matron and maiden, mother and lover, and the novel blends the two in Charlie’s desire for her: does he want a mother to replace his dead one, or a lover to take him into new realms of pleasure, or maybe both in one? Charlie spends much of the novel puzzling this out, trying to reconcile her motherliness with how hot she is—a literalization of Freud’s Oedipal complex. All of this hand-wringing about Elizabeth is ultimately resolved by Elizabeth herself, who banishes the notion that Charlie would ever truly be satisfied loving a “fallen” woman, since he holds on too tightly to his moralized, Victorian notions of love, romance, and marriage to ever truly accept being with Elizabeth. It’s fine to carry on that way on a tropical island removed from British society, but it would never work at home in England. And Charlie ultimately concedes, deciding to give up England completely, it would seem, for life on Oleandra with his queer dolphin life-partner Gloomer.

This last point about the conceptual, if not moral, difference between life at the colonial periphery, on an obscure island in the Caribbean, versus life at the colonial center, in London or at Cambridge, is crucial to the politics of Swann’s The Goat Without Horns. And it’s here, really, where the satire of the Gothic most clearly shows itself as a failure. Already, with regard to gender, I’ve suggested that Swann isn’t doing anything all that interesting, especially if he saw his gender reversals of Gothic narrative forms as the key elements in his satire. Race, too, and especially the spectre of colonialism, haunt the Anglophone Gothic literary tradition as much as gender and sexuality do. At first, it would appear that Swann is keenly aware of this. For when Charlie arrives on Oleandra, he comes expecting adventure: “[h]e had, like the heroine of Northanger Abbey, anticipated something not only different, but barbarous and even threatening” (29), “anything strange and alien and, yes, sinister” (28), to juxtapose against his sense of normalcy, of England. But he finds instead a recreation of an English village and feels “a curious revulsion, even a sense of betrayal. What right had an English village to twinkle on the inner slopes of a crater in the West Indies?” (28).

For all this set up and awareness of the colonial contexts of not only his own narrative, but also of the Gothic itself, Swann’s novel doesn’t challenge these ideologically weighty conceptions of adventure or barbarity or the hubris of an English village twinkling on a volcanic Caribbean island. Yes, Charlie reverses the idea of the colonial other coming to England and visiting its revenge upon the British Empire, by himself leaving England and stepping into the colonial world, where he is now menaced by the very colonial setting he came to experience, but this reversal paired with Charlie’s ultimate turn as the Bryonic hero—casting Curk as the monstrous villain—thwarts any potential for critique. Notions of barbarism and civilization, of Indigenous savages and modern enlightened Europeans, are embedded so deeply in The Goat Without Horns, and most definitely not as objects of satire, that the novel has to be either a terrible, awful failure on Swann’s part to understand what satire is or else a reflection of Swann’s own attitudes toward Indigenous people, the British empire, and colonial modernity. If the latter, Swann appears to be treating as literal and unbiased the early colonial accounts that described Caribs as degenerate cannibals who needed to be slaughtered, enslaved, and civilized.

Time and again, the novel—remember: narrated by a dolphin, who should not be ideologically compromised by human ideas of civilization vs. barbarism, except insofar as he might have learned them from Charlie and thus replicated them in his oral history of Charlie’s life—expresses disdain for the Indigenous Caribs. They are variously “savage,” “barbarian,” “degenerate,” “lazy,” “indolent,” “squalid,” and “slatternly,” worth no more than the garbage-eating curs they raise for the fun of beating. The Caribs of Swann’s novel are agentless, wholly subject to the kingly mastery of Curk, who stands above them all in intelligence, charisma, and looks, so much so that by the end, even after Curk tries to kill him, Charlie can’t help but admire him. As Charlie notes of an earlier meeting with Curk, “he was savage, but not a savage” (102).

Where once the Caribs were a mighty people, Columbus and colonialism have made them “weak and degenerate” (85), “they have almost been exterminated” (93), and Curk hopes to breed Jill with Charlie in order to revitalize the racial stock of the Caribs with the blood of “Englishmen [who…] are used to governing empires” (104). As Curk put it, when he first courted Elizabeth, “[m]y race is degenerate” but hers “is the power of England and the world,” so their child could be “worthy of an empire” (112). Later, when Curk is defeated, the Caribs are rendered even more inhuman: “Now they’re soulless. They’ll settle on another island and grow lazier and meaner, and get themselves killed off completely” (162).

The novel also combines racist ideas about voodoo with racist Western fears that Indigenous cultures practiced human sacrifice. The title of the novel is borrowed from a sensationalized Western account by British diplomat Spenser St. John of a human sacrifice that supposedly took place in Haiti in the 1860s. The account circulated widely in the US and UK, popularizing “goat without horns” as a term for human sacrifices by voodoo practitioners, and it was followed by similar, equally racy “first-hand” descriptions of cannibalism, sacrifice, and other acts of violence that cast Black and Indigenous Caribbean peoples as backward, as everything Swann’s Curk claims his people have become. Importantly, the term “goat without horns” came to mean a white child sacrificed in voodoo rituals.

It’s virtually impossible to read Swann’s treatment of race and colonialism, with all of its racist, genocidal, and eugenic language, as anything but actual racism. Swann may have be keenly aware of the racialization inherent in terms like “goat with horns” or in his use of words like “degenerate,” “barbarian,” and “savage” in such profligate references to the Caribs, but there’s never a moment of pause among the novel’s characters or in its plotting that would suggest anything other than that the narrative takes these racialized meanings as a given. Charlie is even cast as “Rousseau’s noble savage” (153), a leap in nobility beyond what Curk could ever hope to achieve. Curk is called, in the end, a “devolution” in Darwin’s scheme of things, though Elizabeth suggests an alternative: that, yes, humans evolved from apes, but perhaps other animals evolved their own kinds of human, offering a possible Darwinian explanation for all of Swann’s prehumans. She notes, too, that people like Curk existed in the world from ancient times onward, until the Church suppressed them, an idea developed more thoroughly in Swann’s 1976 novel The Tournament of Thorns (165–166). Charlie, however, condemns the idea of other lineages and other types of (pre)humanity and states that any such beings belong “In the world’s past” (166). While Charlie can’t reconcile weresharks with his Victorian worldview, he is somehow perfectly capable of slotting Gloomer—the talking dolphin!—into it and he admits early in the novel to believing in the Sidhe: “the Dark Ones,” “the Little Ones” of Celtic folklore and mythology (62).

It’s difficult, then, to fit The Goat Without Horns into Swann’s larger oeuvre. Notably and perhaps most confusingly, the terms Swann uses for the Caribs are usually reserved in his novels for the prehumans. Barbarian and savage and monster are accusations directed at the prehumans by humans who fear the Beasts or Weir Ones, who see their animality and attunement to nature as unnatural and backwards—as a threat to civilization. This attitude is always vociferously challenged in Swann’s prehuman narratives. But here, in The Goat Without Horns, there is no challenge whatsoever to the hierarchical language of barbarism vs. civilization laid out in Victorian fashion by everyone from Charlie to Curk to the dolphin Gloomer.

Jill is a unique character in this regard, a possible locus for the novel’s supposedly satirical energies to show up the racism for what it is. That she is enamored of the Caribs is presented initially as a sign of her antithetical relationship to Victorian society and British empire: she doesn’t want to be a lady and she doesn’t want to be English. By the end, though, we learn that it’s the romantic idea of Curk’s reborn Carib empire that drives her. It is her kingly Carib father’s supreme masculinity and power—usurped, in the end, by the victorious Charlie—that sets her against everything British and Western. The Caribs themselves, as a living people and colonized culture, mean nothing to her. And by the end, with Curk dead and the Caribs departed to other shores, to “grow lazier and meaner, and get themselves killed off completely,” Jill admits that what she loves most is Charlie’s combination of kindness with power, which far surpasses her father’s meanness. On this final point, the novel is sincere—in fact, power tempered by kindness is the masculine ideal across most of Swann’s novels. So there is no satire here. In any other Swann novel, Jill would be proven right in her admiration for the Caribs, who might have been understood as a people unjustly wronged first by centuries of colonialism and now by a megalomaniacal leader with pretensions to godhood. Or Curk would be played up as a truly tragic figure, not as the monster who did, indeed, need to be killed.

Perhaps the point of this narrative framing, whereby the Caribs are presented as truly degenerate and backward, is that characters like Charlie—and by implication Gloomer, who seems to have learned a great deal from Charlie and agrees with his worldview insofar as he has essentially “written” a hagiography of the rather bland Charlie—can only see the world through their own lenses. Charlie can only understand Curk or werebeasts or prehumans through the epistemic regimes of Victorian society and science and all the ideological assumptions they smuggle in. This is a somewhat compelling reading that resonates with Swann’s other writing. Take, for example, The Tournament of Thorns, where John and Stephen are unable to see the initially monstrous Mandrakes for what they are, though Lady Mary ultimately does and accepts the Mandrakes as her family, rewriting her own past and identity in the process. But that novel treats the inability of John and Stephen to reconcile the Mandrakes with the history that has made them what they are, and their current treatment by medieval English society, as a tragedy. There is no such sense of tragedy, of loss, in The Goat Without Horns. A great many of Swann’s novels are explicitly concerned with human characters changing their sense of the world in order to more empathetically engage with prehumans and understand the injustice of prejudices against them. None of this is present in The Goat Without Horns. Either because Swann failed to pull off his satire of race/racism/colonialism, or, more probably, because it reflects his actual prejudices. And that’s a real shame given the themes of his work.

If there is a critique of colonialism in The Goat Without Horns, it is really only present in the name of the island where the action takes place. The act of renaming Oleandra is an act of symbolic colonization by Elizabeth, secondary to the political and economic contexts of the British colonization of the Caribbean that allowed her former husband to purchase the island as the Meynells’ own personal playground in the first place. Elizabeth renames the island after the beautiful but poisonous oleander flower, taming the original Indigenous name of Shark Island, papering over the implications of that earlier name and dismissing it as mere superstition. The Indigenous people are ultimately proved right. The name is not only ecologically appropriate, as attested in the dolphins’ traditional ecological knowledge that understands the island to be teeming with sharks, but it is also historically and theologically appropriate, since the island is the last home of the prehuman weresharks and of the Carib shark-god Tark’s cult. And, at the same time, the colonial name, despite hiding the Indigenous name’s implications, nonetheless (re)affirms the island’s dangers at both the narratological level and the storyworld level: Oleandra itself, and everything that takes place there, is beautiful but deadly. And because the oleander is a tropical flower, not suited to English gardens, but nonetheless cultivated on colonial estates across the empire, the name serves as a further reminder of the efforts of empire to domesticate, beautify, and forcibly transform the world in the name of Queen Victoria and her subjects.

Parting Thoughts

Finally, a few stray thoughts on this frustrating novel.

The first is that the novel’s “noble savage” hero, Charlie, is named and modeled after the WWI poet Charles Sorley (1895–1915), who died at the Battle of Loos. Charlie is educated at the same institutions—Marlborough and Cambridge—though his family situation is different, being a recent orphan. He, too, is a poet. Where Charlie writes epic poetry, seeking to compose a nationalist narrative about the Celts and Romans and Saxons and Normans (62), Sorley wrote poems reflecting on the horrific nature of war as he experienced it. Sorley was a favorite of Swann, who wrote what was probably the first monograph on the poet: The Ungirt Runner: Charles Hamilton Sorley, Poet of World War I (1965). Moreover, Sorley is now considered to be one of the many British WWI poets who was probably queer. I’ve already written about Swann’s attention to queer poets in my essay on Lady of the Bees, but it’s worth noting that his vision of Sorley here—and it has to be made clear that this Charlie is both the same and different, born several decades before the historical Sorley—is of the Byronic hero, cast as an English nationalist, with a deep knowledge British poetry, who loves a woman through layers of psychosexual complexity, and who ultimately rejects England and heterosexual love to stay in the Caribbean with his queer dolphin life-partner. We’ll see soon how Swann handles another, much more famous queer poet, Sappho, in Swann’s second Ballantine novel, Wolfwinter (1972).

The second is that, as I’ve noted in just about every essay on Swann’s novels so far, including this one, Swann tends to pair up male characters in these distinctly yet elusively queer relationships. They are often framed, too, as brotherly relationships; occasionally, the word “comrade” is used. In a 1974 letter to his good friend Bob Roehm, Swann described spending his childhood in want of a sibling, always promised, never to come. Swann felt that his novels positioned himself metaphorically in the spot of Gloomer or Stephen or Remus in search of a Charlie or John or Romulus (see Robert A. Collins, Thomas Burnett Swann: A Brief Critical Biography & Annotated Bibliography (1979), 6-7). I don’t doubt that this is an important reading of Swann’s male-male relationships, but as I think I’ve made clear over the tens of thousands of words I’ve written about Swann so far, there is a distinct queerness to all of these relationships (only the Romulus/Remus one is significantly different; there, in Lady of the Bees, the queer desire connects Sylvan and Remus).

The third is that the story of The Goat Without Horns seemed uniquely personal to Swann and his own health experiences. In a 1969 letter to his (former) department chair at Florida Atlantic University, William Coyle, Swann complained that he was persistently troubled by a severe urinary tract infection, treatment of which did major nerve damage and, for whatever reason, led to him being something of an invalid. In his letter, he compared himself to “the poets I admire,” among them Keats and Elizabeth Browning, saying they had managed better; he was more like Byron, whose “glandular disturbance” “made him fat. I guess he felt about as I do about my ailment” (Collins, 5). Given the timing of the letter, Swann must have been either writing or planning to write The Goat Without Horns in its serialized form for F&SF. In his letter, he names three of the major poets whose work animates and reappears time and again in The Goat Without Horns. Given the explicit comparison with these poets, his novel casts him in the role of Elizabeth, an invalid who, like Mrs. Browning, fared better than Swann in his condition. Not for nothing, Elizabeth—who takes Swann’s role as the invalid—is the romantic ideal and object for Swann’s beloved Charles “Charlie” Sorley. The intertextuality with his personal life suggests some compelling readings.

The last is that, for whatever reason, there seems to be another connection to dolphins on Ballantine’s recent, growing genre fiction list: namely, Roy Meyers’s trilogy consisting of Dolphin Boy (1967), Daughters of the Dolphin (1968), and Destiny and the Dolphins (1969). The first two were labelled sf, but the final novel got the same genre classification on the front cover as Swann’s The Goat Without Horns: “Fantasy Adventure.” I haven’t read these novels, but they seem to feature a civilization of intelligent dolphins not unlike Swann’s, and revolve around human-dolphin relations when dolphins decide to raise a human, who comes to be called Triton, lives a partially underwater life, and in turn helps raise other humans in the dolphin way. Not for nothing, Swann’s dolphins praise a progenitor god called Great Triton. I don’t know that there’s any explicit influence, if Swann ever even read Meyers’s novels, but no doubt Betty Ballantine might have seen Swann’s own dolphin novel as a natural companion to the earlier dolphin trilogy she’d already published.

All of this is to say that Thomas Burnett Swann’s The Goat Without Horns is a Frankenstein’s monster of a conundrum. It’s wonderfully written, deeply intertextual with nineteenth-century British literature and with Swann’s own increasingly complicated life, wonderfully queer in the weirdest, coolest sense possible (without, sadly, committing more to that queerness!), and also remarkably racist. Swann felt that readers misunderstood his satire and it seems to have deeply hurt him. I think he just wrote a bad novel.

To get notifications about new essays like this one sent directly to your inbox, consider subscribing to Genre Fantasies for free:

much to consider here — the juxtaposition of a belief in “Celtic” fairies with Indigenous supernatural beings reminds me of Francis Stevens’s The Citadel of Fear, for one — but I’m really interested in the choice to center on Caribs in a book set in the 1870s.

assuming that Swann was unaware of Garífuna people and/or the related “Black Caribs” on Saint Vincent, this choice feels extremely marked for a book set in the Caribbean, particularly for a book published in the middle of decolonization and at the height of the Black power movement. I’m wondering if the choice of Caribs (still too often presumed to be all dead/gone and so written out of the political, historical, and cultural imaginaries of the Caribbean) was specifically to avoid engaging with Blackness in the context of this period — Swann’s Caribs can “safely” disappear out of (pseudo)history and leave behind only white/creole (in the older sense of Euro-descended and/or partially white) people without Swann having to engage with Black or Indo-Caribbean history/presence/politics, because common knowledge (still) holds that there are no more Indigenous people in the Caribbean.

LikeLike

Yeah, I think that’s probably right! There are two mentions of Black folks in this novel. One is of enslaved Africans getting free and landing on Oleandra, only to be eaten by the Caribs. The other is that the Caribs have adopted “Negro” speech patterns.

But choosing an Indigenous people generally thought extinct probably made sense to him for all the reasons you suggest. The key difference with and curiosity about the Sidhe comparison, though, is that the Sidhe are something to be marveled at for Charlie. They left b/c the world got bad (as in other prehuman stories). The Caribs, however, according to Swann, simply weakened and became “degenerate” (though the comparison here might be made with the Mandrakes of Tournament, who are “degenerate” but also tragic figures).

The only novel where Swann deals more explicitly with Blackness is, I think, Minikins of Yam. But I’m not yet there so idk how he handles Blackness — and if he does! That said, Swann’s scant references to “Libyans” and folks with Black skin in other novels tend to be quite negative. So we’ll see! But I honestly had thought going in to this novel that the villain was going to be Black b/c of setting but also the voodoo reference in the title. Blackness seems always at the edge of his work. We’ll see if it even comes up in his final novel, Queens Walk in the Dusk, which is set in Carthage and should at least have reason to reference Black Africans.

LikeLike