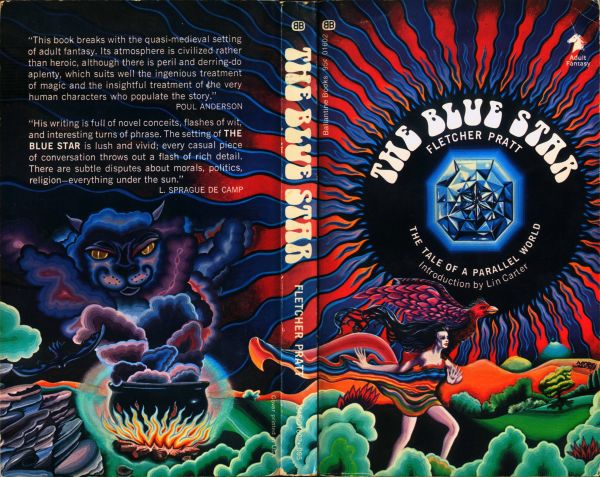

The Blue Star by Fletcher Pratt. 1952. Ballantine Books, 1969.

This essay is part of Ballantine Adult Fantasy: A Reading Series.

Read Lin Carter’s introductory essay here.

Table of Contents

Fletcher Pratt and BAF’s Beginnings

Reading The Blue Star

Parting Thoughts

Fletcher Pratt and BAF’s Beginnings

Welcome—or welcome back—to Ballantine Adult Fantasy: A Reading Series, a project to read through the massively important Ballantine Adult Fantasy series published by Ballantine Books, under editor Betty Ballantine and with the assistance of consulting editor Lin Carter, between 1969 and 1974. The series arose in the wake of Ballantine’s blockbuster success reprinting Tolkien’s The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings trilogy in mass market paperback in 1965, and it played a crucial role in the “genrefication” or the emergence of fantasy as a mass market genre—that is, as a literary form that was recognizable and sellable as a category within the publishing industry. By the end of the 1970s, thanks in large part to the influence of Ballantine’s BAF series, which focused mostly on reprints of older books, many out of print, and released a total of 65 books (mostly novels, but some story collections, too), nearly every mass market paperback publisher had a line of fantasy novels and science fiction had a sister genre on bookstore shelves.

When we talk about fantasy’s history before its emergence as a market genre, we often talk about two lineages of fantasy that came together in the 1960s and 1970s to map the historical horizons of the new genre: the “literary” tradition of mostly British authors, especially the work of Tolkien, William Morris, Lord Dunsany, E.R. Eddison, and James Branch Cabell, and the popular fiction tradition of mostly American authors, especially the sword-and-sorcery pulp fiction of Robert E. Howard or C.L. Moore, and the “rational” fantasy encouraged by John Campbell in his short-lived magazine Unknown, which included and influenced authors like Manly Wade Wellman, L. Ron Hubbard, Theodore Sturgeon, Fritz Leiber, L. Sprague de Camp, and Fletcher Pratt. In its five years, BAF blended these two broad lineages of fantasy’s pre-genre history, reached beyond them (for example, to medieval and ancient texts), and brought in a handful of new authors, like Katherine Kurtz, leaving behind a rather diverse canon of fantasy “classics” for the fledgling genre to learn from.

The first book in the BAF series, released in May 1969, was Fletcher Pratt’s The Blue Star. Pratt (1897–1956) was the sort of absolute character whose life seems too wild to have been real and you suspect a great many of the stories told about him to be fabrications or stretches of the truth. Most of what we know about Pratt’s life comes from his regular collaborator, L. Sprague de Camp, who dedicated a chapter to his deceased friend in Literary Swordmen and Sorcerers (Arkham House, 1976). Pratt was a boxer, librarian, journalist, and military historian; a staunch political conservative who nonetheless held liberal(ish) views on race and gender; a Christian Scientist who enjoyed cigars and alcohol; and a fantasist who disliked much of the pulp fantasy then available. He wrote fantasy in the Campbellian “rational” mode that sought to import from science fiction a supposedly more logical, more rigorous, more scientific approach to the fantastic (hence the original meaning of the term “science fantasy”). In this mode, Pratt and de Camp co-wrote The Land of Unreason (1942) and The Carnelian Cube (1948), as well as several stories in the Incomplete Enchanter and Gavagan’s Bar series. Altogether, Pratt wrote dozens of books, mostly nonfiction, and two independent fantasy novels of his own: The Well of the Unicorn (1948) and The Blue Star (1952).

The Blue Star initially appeared in a 1952 hardcover collection of three short novel(la)s released by Twayne Publishers and edited by Pratt himself (though uncredited). The collection, Witches Three, paired Pratt, Fritz Leiber, and James Blish, and only Pratt’s novel was original to the volume, the other two having been published in 1943 and 1950, respectively (Leiber’s piece was published Campbell’s Unknown during its final year). But Twayne’s hardcovers had limited circulation and small print runs, making them collectors’ items even by 1969, so Pratt’s The Blue Star was largely unknown outside of specialist and collector circles. While The Blue Star was the first official BAF novel, and the first to sport the now legendary unicorn logo, Ballantine published a number of novels between the 1965 success of Tolkien’s mass market editions and May 1969, which were dubbed “preface” novels by series consulting editor Lin Carter (a handful of these were later reprinted with the unicorn logo).

I spent last year writing about the BAF “preface” novels, charting the early history of pre-genre fantasy, and setting up the important cultural, historical, and industrial contexts that led to fantasy’s emergence—and, of course, focusing on BAF’s role in this literary-historical process. If you’re new to this series, I recommend starting with the landing page and then my essay on Peter Beagle’s The Last Unicorn (1968), which was the first in this reading series, despite being out of order, and as such provides a detailed background to the series and references to some important secondary materials, such as Jamie Williamson’s The Evolution of Modern Fantasy, that inform my scholarship in this series. Another good starting place is my essay on Carter’s nonfiction book Tolkien: A Look Behind The Lord of the Rings (1969), since that book got him the job as consulting editor for BAF and suggested to Ballantine Books that there was a whole archive of “books like Tolkien” that could be brought together as “adult fantasy.” Tolkien also establishes Carter’s understanding of fantasy and its history, which greatly shaped the BAF series, not least through his text selections but also through his introductions, which appeared at the beginning of each volume, provided information about each author and novel’s history, offered brief notes on a novel’s themes, and wove each book into the larger tapestry of fantasy as Carter understood it.

To be sure, The Blue Star is a strange novel with which to launch BAF, especially given Carter’s understanding of the “epic fantasy” tradition to which Tolkien belongs and which he saw himself stewarding through BAF’s text selections. Carter’s “epic fantasy,” as outlined in Tolkien, was a story that had invented settings, wars between two sides, quests, cognomial weapons, supernatural beings, and magical artefacts. Carter is never clear whether epic fantasy requires all of these elements or just some of them, but these are the building blocks of epic fantasy outlined in his 1969 book. Introducing The Blue Star, Carter further suggests that “epic fantasy” is his own coinage, but his usage often confuses the term with another, then more common, one: heroic fantasy, which was used by some to delineate what is also called sword-and-sorcery (a genre which Carter claimed in Tolkien was most definitely not epic fantasy; he doesn’t explain why—he doesn’t explain a lot!). The point here is that Carter’s terms for and taxonomy of fantasy were in active flux and redefinition during the BAF period, so we have to pay careful attention to his deployment of terms in their given contexts.

In the introduction to The Blue Star, Carter describes epic fantasy as “the huge, crowded novel of warfare, quest[,] and adventure which takes place in an imaginary pre-industrial age worldscape of the author’s own invention” (vii–viii). The Blue Star is hardly epic fantasy by Carter’s definition: it is neither huge nor crowded, but a shorter novel of 240 pages focused on a small handful of intimately connected characters, even if the stakes are high; it is not about warfare but about political intrigue at an imperial court and almost no scenes of action; there is neither quest nor adventure, only the flailing and increasingly beleaguered responses of the novel’s protagonists to worsening circumstances; and it is not a medievalist fiction, as so much epic fantasy is, though it is pre-industrial. The tension between Carter’s epic fantasy definition and The Blue Star is unsurprising, since Carter is a rigorously uncareful critic and never fails to overlook the specifics, but it’s a productive tension that tells us a lot about the desire—not just Carter’s, but publishers’ and fans’, too—to identify a singular, unified understanding of the emergent fantasy genre.

Reading The Blue Star

The Blue Star is an exceptionally good novel and was an excellent choice to launch a series that intended to demonstrate the literary virtue of “adult fantasy”—or, rather, to demonstrate that fantasy was not merely a category of children’s fiction. The Blue Star is a tight, meticulously plotted, densely imagined, and excitingly political tale of two sort-of-lovers set in a fantasy world that vaguely resembles eighteenth-century Central Europe, which both Carter and de Camp identify with the Austro-Hungarian empire under Maria Theresa (r. 1740–1780). In Pratt’s world, magic is real but limited, practiced only by a handful of witches who pass magic down hereditarily from mother to daughter. Witches and their magic are surveilled and oppressed by both political and religious institutions in Pratt’s world, especially by the Church that provides the ideological force behind the Dossolan empire’s worldly rule. But Pratt’s world is not the unipolar fantasyland composed of a single state with one religion and one language and an unchanging history stretching back thousands of years. Pratt scoffed at simplistic fantasy adventures whose worlds were thin and ill-conceived, worlds that, in other words, were not like the real world, not the product of complex histories and conflicting peoples and changing economic, political, technological, and social conditions unevenly distributed across the centuries.

There is in The Blue Star not just the nation of Dossola, ostensibly ruled by the Queen but ultimately controlled by a small council of ministers, like Chancellor Florestan and the rakish foreigner Count Cleudi, but there is also Dossola’s recently freed colony of Mancherei, which rebelled when the Queen’s heir, Prince Pavinius, acting as the governor of the colony, became the Prophet of a new religion that rejected the Church and its God of joy in favor of a God of love who understands the material world to be evil. The revolt of the Prophet and the new Amorosian religion led to the creation of a new state in Mancherei, a pseudo-communist one where no one goes hungry and everyone has work, so long as they obey the religion’s Initiates—otherwise, they are sent for “instruction.” Mancherei could not have broken free from Dossola, though, had the empire not been at war with Tritulacca, a nation that claims right of rulership over several of Dossola’s provinces. With Mancherei split off and Tritulacca always ready to war for Dossolan land, there’s also trouble at the border with Mayern, a small state where now dwells the former Prophet, exiled from Mancherei on account of his later religious writings, which the Amorosians found to be heretical to the very religion he created. And if these geopolitical issues were not enough, Dossola is flat broke, payments to the army and civil servants are months in arrears, and the nobility refuses to pay further taxes.

When the novel opens, enemies harry Dossola’s borders and revolution is brewing in its cities. The Sons of the New Day are the principal force for change in the novel, a revolutionary group seeking equality of classes, not unlike the revolutions of 1848 that shook European nations. Both de Camp and Carter—and everyone else since them—refer to the Sons as “Bolsheviks,” but I think this comparison has more to do with their interpretation of the political violence the Sons ultimately unleash when they “win” and establish their people’s courts, than it has to do with any ideological resemblance between the Sons and the Bolsheviks (the French Revolution and Nazi Germany also had people’s courts to try political dissidents and ideological enemies). The revolutionary message of the Sons is contrasted with that of the Amorosians, who also want equality for all, but within a religious framework that strictly denies the material world and that believes in a cycle of karmic rebirth (with bad people reborn as insects), paired with ultimate obeisance to the law of love (i.e. selfless action that, ultimately, benefits those in power). The Amorosians’ religion reads as a mixture of Buddhist, Christian Science, and Manichaean ideas (they believe, for example, that the material world is the creation of the equally powerful God of evil).

While Pratt’s rich worldbuilding is remarkable for so short a novel, his presentation of magic is the book’s major innovation and quite a unique one. Magic in The Blue Star operates almost like a science-fictional novum, it is not just a learned practice, a domain of knowledge consisting of “patterns” traced in liquid, which acts as spells, but it is also genetic: a woman can only do magic if she is from a witch bloodline. But she can only work magic after she loses her virginity; at that point, her mother loses the ability to cast spells and is magically impotent for the rest of her life. Moreover, whatever man the witch considers her “lover” gains the use of an eponymous Blue Star, a jewel that grants the man the ability to read people’s true intentions (but not exactly their thoughts) when he looks them in the eye. But should he betray his witch, specifically through the physical act of sex with another woman (or man, I assume?)—emotional dalliances, make out sessions, and even breast fondling are all fair game (there’s a great deal of all of this in the novel)—then he will lose the power of the Blue Star, which the witch can then gift to another, (hopefully more) faithful (male) lover. The implications for how the novel deals with gender, sex(uality), violence, and oppression are numerous and Pratt explores them thoroughly. Indeed, The Blue Star is very much a novel about sex and gender and the social structures that order them.

That magic operates almost science-fictionally as a structuring force for Pratt’s worldbuilding owes to the author’s own ideas about fantasy and the “rational” fantasy lineage to which he belonged, as noted above. A further symptom of this is Pratt’s use of a framing device that many critics, Carter included, find awkward and distracting. The novel opens not in Dossola and its world of witches and Blue Stars, but with an abstruse philosophical discussion among some armchair philosophers, ostensibly in our world and time (well, Pratt’s), discoursing on whether all parallel dimensions would evolve in the same way or in radically different ways. These philosophizers imagine, for example, a world without gunpowder, which they take to be the most significant invention in modern history, and replace it with the very magic system described above. Carter so disliked this framing device that he suggested, “you can skip it and get straight to the story,” but what he doesn’t highlight is that the frame is not only key to Pratt’s “rational,” science-fictional approach to fantasy, but also a reference to one of his favorite works of fantasy, E.R. Eddison’s The Worm Ouroboros (1922), which opens with a similar “induction” into the fantasy narrative and which, I argued in my essay on that book, is actually quite fascinating.

It’s into this complex, swirling, swelteringly alive storyworld with its strictly ordered hereditary magic system and its threats of revolution and invasion, into this dream of the rational philosophizers of fantasy, that the novel’s protagonists, Lalette Asterhax—virgin daughter of a witch and soon-to-be witch herself—and Rodvard Bergelin—low-ranking clerk in the Office of Pedigree (genealogy records), low-level member of the Sons, and soon to be Bearer of a Blue Star—are thrust. Lalette is pursued by the Count Cleudi of Tritulacca, who serves the Dossolan court in a ministerial position, but Lalette wants only to be a free woman, to choose her own path in life, and not to have life dictated by an arranged marriage. She is poor, has learned the witch-patterns from her mother (who is carefully watched over by one of the Church’s “Uncles” or priests), but has no desire ever to become a witch and so be either a victim of the Church or a tool for others. Rodvard is tasked by the Sons with seducing Lalette, making her a witch through sex, and gaining the control of her Blue Star, so they can use it in service of the revolution.

Rodvard succeeds in his mission in an uncomfortable scene where he forces himself on Lalette, who struggles, protests “Let me go. It’s wrong. It’s wrong” (18), and asserts that she has no desire to become a witch. But Rodvard pushes her until she relents and, under great pressure, “consents.” The scene is dismal and just a hair’s breadth away from rape. Lalette and Rodvard hardly like each other to begin with, but Lalette sees in Rodvard a possible freedom from the arranged marriage to Cleudi, and Rodvard sees in Lalette only a means to an end: his “high destiny” of aiding the Sons of the New Day. After the sexual encounter/assault, both are distraught, Rodvard dismayed that he’ll likely have to marry Lalette now, instead of the baron’s daughter Maritzl whom he has his eye on. And Lalette is disgusted at having been both used and having taken possession of her witch-powers. All of this occurs in the novel’s first twenty pages. And what ensues for the remaining 220 pages is a madcap stumble between rocks and hard places for both Lalette and Rodvard, which begins when Lalette accidentally hexes Cleudi and must flee the city, and with Rodvard agreeing to help her, since she has, after all, given him use of the Blue Star.

The bulk of the novel sees the two split apart, as Rodvard is sent by the Sons to the imperial court to use his powers to spy. He has been commissioned as Cleudi’s secretary and in no time is embroiled in court politics, learns of the failing finances of the empire, helps Cleudi ruin several nobles’ reputations, and—horny bastard that he is—loses the use of the Blue Star by fucking a maid. He must flee the court when another noble suspects his role in a cuckolding, and he regains the use of the Blue Star when a witch-wife (sort of like a hedge witch) accidentally restores its power for him, but despite that lucky turn, he is carted off to Mancherei, nearly raped by a gay ship captain, and forced into clerical labor by the Amorosians (and again almost loses the use of the Blue Star when he falls for the daughter of the shopkeeper his is boarding with), until he serendipitously discovers Lalette is also in Mancherei. She, too, has been through the ringer, aided in hiding from the Dossolan provosts and episcopals by Amorosians and Zigraners (an ethno-religious minority that mixes elements of Jews and Roma), pursued sexually by man after man, and smuggled to Mancherei, where she winds up in a religious brothel that serves the Amorosian Initiates who administer the state. Rodvard tries to break Lalette out and flee Mancherei, but the two are as incompetent as ever and wind up in prison—only to be rescued by agents of the Sons, who declare that Rodvard and Lalette are needed in Dossola now that the Revolution is underway.

Back in Dossola, Rodvard serves the Sons by reading the intentions of the various nobles, episcopals, and elected officials who make up the new governing council of Dossola (the Queen and court are in exile). Of course, Rodvard isn’t very skilled at this and he has little to offer the Sons, so is shunted into working for one of the people’s courts set up to try Dossolan elites for crimes against the people, which mostly amount to ideological disagreements with the revolutionary aims of the Sons. Lalette, for her part, is courted in secret by one of the Sons’ agents, and she again laments that all men seem to want from her is sex. But this agent also steals secrets told to Lalette by Rodvard. The Sons want Lalette to help locate women from witch-families, so that she can teach them the patterns and help put witches in the new state’s employ. But Lalette, having always feared how her skills make her into a tool for others’ use, decries not only her loss of autonomy but also having to inflict that fate on other girls. Rodvard and Lalette come to the mutual recognition that they have spent their lives used by others, manipulated by institutions of power, and victimized by the state, and that so long as they remain in the center of things, they will never be free to be whomever or whatever they could be. So they escape, and in their escape they find that, just maybe, they actually do love one another. They end the novel, then, by throwing the Blue Star into a river, literally and symbolically rejecting the power and uniqueness that has upended both of their lives and which made them objects, tools, not people.

This is, to be sure, a whirlwind description of a complicated and convoluted little novel, which sparkles with life and detail and emotion. Pratt’s writing is unique, mixing both a literary style and flair for manipulating grammar and punctuation in uncanny ways, so that sentences do and say more than they would at first appear to, with a pulp writer’s sensibility for succinctness. His characters, too, are fascinating. Rodvard, for example, is almost entirely unlikable. He is pathetic, annoying, and gets hard at the slightest glance from a woman. He forces Lalette into her witchhood and manipulates her so that he can use the Blue Star for the Sons (she only finds out about his affiliation much later, and is disgusted). And yet, while some critics have suggested that Rodvard is too much of a wet noodle to be a worthwhile protagonist—certainly, he is no hero, and I don’t think Pratt was writing heroic fantasy by any means, but rather its antithesis—Rodvard’s function in the narrative is to show how poverty and low status combine grotesquely to create a life wherein one’s choices are constrained, where even the revolutionary ideals of the Sons and the Amorosians will batter men about in order to see their goals accomplished. Rodvard is a cog, a servant of others’ destinities, and he knows it, he wonders at it, and in the end he chooses to give up that cruel optimisim—the Blue Star—which binds him to this fate.

Rodvard is not a good person, and he causes people great harm, most especially Lalette, who is doubly victimized by his actions at every turn, but the novel makes explicit that it is interested in what, exactly, makes a “good” person. More than anything, The Blue Star is about how political, social, legal, and religious systems produce (and discipline) people, whether those systems tend to make people who are (morally) “good” or “bad,” and how the power accrued in any system affects the individuals acting and living within those systems. Pratt also details the myriad contradictions that flourish in complex social systems, which allow people to justify their lives and actions in relation to that system (this is especially true in the chapter set in Mancherei, where everyday Amorosians tackle what it means to serve the God of love, to live by the Initiates’ virtues of self-sacrifice and denial of the evils of the material world, and to do so out of a distant fear of being sent for “instruction”). In short, Pratt’s fantasy novel is about some of the major questions of political science and political philosophy, and it treats these concerns with care and quiet attention by focusing on the lives of two people who are caught up in the torpor of political machinations and social maneuverings that go far beyond them. Rodvard, who is not a hero and not really an anti-hero either, so much as a guy who somehow lives through the novel, is the heart of Pratt’s questioning of authority, power, and ideology.

Pratt doesn’t exactly offer answers, but then, there are no clear and final answers to these questions—hence, thousands of years of philosophy and religion and warring political systems. What Pratt does give us is a tour and inventory of different ideas about power and goodness and ethical action, from the feudal system of Dossola to the revolutionary ideals of the Sons to the Amorosians’ God of love, and he shows how all of these systems fail in one way or another because they allow power to inhere and corrupt—hence, too, why the Prophet/Prince Pavinius, was exiled from Mancherei: because he disavowed the new state’s accrual of power and its system of discipline and social control in its effort to serve the God of love that he revealed through his writings. Through their choices to abandon the Blue Star, flee their new lives at the center of the revolution, and swear off witchery, Rodvard and Lalette reject the coercive narratives with which power seeks to interpolate us all.

But Lalette is perhaps the more important and certainly the more interesting character in The Blue Star. De Camp, Carter, and a number of critics since have referred to Lalette as “shrewish,” likely because Lalette, quoting her mother, worries that she is shrewish. And both she and Rodvard (and the novel’s critics) decry her “temper.” But, my gods, there is nothing shrewish about Lalette and, if she occasionally chides Rodvard (only to later apologize and try to express her unfathomable love for this loser), it is because Rodvard fucking deserves her ire and Lalette has every right to be angry. Not only is she forced into sex and forced to become a witch, a thing she dreaded and swore never to become, but she is separated from her mother, thrust into exile, pursued aggressively by just about every man she meets, accidentally hexes one into killing himself when he tries to rape her, gets imprisoned in a brothel, and finds out that she bears all of these hardships because Rodvard was an agent of the Sons who merely sought the powers of her Blue Star. She learns, in the course of her harrowing experiences, that she, as a person, is incidental to everyone’s want of her. They desire either her body or her magic or her knowledge or the Blue Star.

Lalette’s self-characterization as shrewish and ill-tempered, and the novel’s insistence on these as facts (with Rodvard, the cause of all her miseries, agreeing and accepting her apologies for her behavior), certainly read like how a politically conservative man’s imagination of a woman’s understanding of herself. And yet, at the same time, Pratt writes Lalette as keenly aware of the patriarchy of it all. She comments about existing only for the pleasure of men, about her frustration that everywhere she goes she is pursued by another man, about her desire, quite simply, to be free of sex and lust and romance and all the ruin they have brought to her life—and these all read as canny critiques of patriarchy and sexism. Pratt gives us extensive internal monologue for both protagonists throughout the novel and, rather than brushing off the sexism Lalette experiences, rather than normalizing it, she highlights its unfairness, emphasizes the unequal situation her sex and gender put her in, and critiques the systems of religion, law, and social practice that keep her in her place. For a novel written in the late 1940s, published in the early 1950s, and re-released in the late 1960s, The Blue Star is shockingly adept at mapping patriarchal ideology and violence, and the ways different systems of power manipulate gender, always to the detriment of women. Not for nothing, Pratt told de Camp that his next fantasy novel—never written—would focus on a woman, “because I’ve learned that my female characters are stronger than my male ones” (qtd. in de Camp, Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers, 192; the outline plot of that novel, however, sounded quite sexist).

The gender politics of The Blue Star are messy, to be sure, but they are compelling and they enhance and complicate the novel’s concern with what it means to be a “good” person, while placing even greater emphasis on the multifarious nature of power. No doubt, for readers in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the novel resonated with the equally messy gender politics of their time, which swirled with new ideas about feminism and gay and lesbian liberation (Pratt does mention both gays and lesbians in The Blue Star, but has no kind words, only contempt), and new ideas about relationships between men and women, both at the individual and social levels. For some, I imagine, The Blue Star would have proved quite provocative in its deft portrayal of the experience of sexism by women and the ways in which even revolutionary and ostensibly more egalitarian social systems still enact patriarchy. And surely the novel’s disavowal of power, its emphasis on how all systems trap individuals, how they cannibalize even their most loyal servants, resonated. The Blue Star, after all, ends with a scene that might, in the late 1960s, have read as an allegory for draftees fleeing the American war machine.

Parting Thoughts

Fletcher Pratt’s The Blue Star was a powerful beginning to BAF that demonstrated the seriousness and intellectual capacity of this thing called “fantasy.” It is a stunningly smart novel, yet not without its problems, and is artfully if economically written (although Ballantine should be faulted for having a typo in the novel’s third word: should be “the” instead of “he”). Published on the heels of so many preface novels from the “literary” lineage of pre-genre fantasy, following in the footsteps of J.R.R. Tolkien, E.R. Eddison, Mervyn Peake, Peter Beagle, and, yes, even David Lindsay, Pratt’s The Blue Star was something different, and yet just as accomplished in its storytelling, worldbuilding, literary art, and its use of all of these to say something through fantasy—to comment, with the affordances of the emergent genre, on politics and power and religion and ethics and gender and more. It also has a strong anti-authoritarian impulse that, I think, puts The Blue Star firmly in the camp of the anarchist fantasy tradition identified by Gifford in his landmark book A Modernist Fantasy (2018).

Toward the beginning I suggested that Pratt’s The Blue Star is not really epic fantasy at all and is certainly not heroic fantasy, though I’ve seen it labelled as such by several writers and critics (including, oddly, de Camp). I think it’s enough to say that The Blue Star belongs to the Unknown tradition of “rationalized” fantasy, but it also draws on the tradition of the Ruritanian novel, which critiques the social and political climate of the times by safely removing that critique to another, imagined nation, usually somewhere in Central Europe. Pratt’s novel is, of course, a parallel world and so not a Ruritanian novel proper, but the novel seems clearly to have been an influence on later entries in the form, most notably Ursula K. Le Guin’s Orsinian Tales (1976). The Blue Star seems also to presage “realistic” political fantasy novels, with the most obvious one being George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series. Setting aside that The Blue Star uses “ser” in place of “sir,” as does Martin, A Song of Ice and Fire shares Pratt’s interest in low fantasy, political machinations, tax policy and the minutiae of rule, characters that are hard done by the unequal systems of their feudal worlds, and the ultimate inability to escape systems of power. Of course, I don’t know that Le Guin or Martin ever read or particularly cared about The Blue Star, but Pratt’s impressive novel nonetheless prefigures both writers’ fantasies, and more importantly the things they did with fantasy, in important ways.

As a final thought, I want to turn to the novel’s true end. Remember those philosophers whose discussion frames The Blue Star, and which establishes that the story of Rodvard and Lalette is their dream of the parallel world they rationally extrapolated? Well, The Blue Star returns to them in the epilogue. They awake, discuss their shared dream (namely the presence of so much sex, which they claim resulted from the prominent role of religion in the storyworld, since religion “is so often an outgrowth of sex—or a substitute for it” (240), another way of saying that one of religion’s core functions is to discipline sex), and when one of them wonders aloud whether the fantasy world really exists, another quips, “I wonder if we do.” It’s a witty response to such a question, almost the knee-jerk one, but it cleverly points to the meta-narrative: of course these armchair philosophizers don’t really exist, because they are in the novel! (Or do they exist, by virtue of our making them real through our reading of the novel?) It’s a subtle, final touch and underscores that even the “rational” fantasy of The Blue Star is, fundamentally, a little bit irrational—just as unreal, just as constructed, and perhaps just as unknowable as reality itself.

And with the first entry in BAF crossed off the list, Ballantine Adult Fantasy: A Reading Series move on to the series’s second book, a true classic of fantasy that, unlike Pratt’s sadly now mostly forgotten novel, is still regarded as masterpiece of the genre’s early history today: Lord Dunsany’s The King of Elfland’s Daughter (1924).

To get notifications about new essays like this one sent directly to your inbox, consider subscribing to Genre Fantasies for free:

”The Blue Star seems also to presage “realistic” political fantasy novels”

That goes double for Pratt’s earlier The Well of the Unicorn, which I think is second only to Tolkien in its influence on fantasy-boom fantasy. I’d love to get your take on that, but sadly it wasn’t reprinted as an AF volume.

Looking forward to rereading The Blue Star with this article in mind.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, definitely! I intend to read it soon, probably next year, since my project isn’t limited to BAF but looks at fantasy generally (I’ve got Del Rey/Ballantine’s reprint from 1976). And I know that Well of the Unicorn is often thought of as the good American fantasy fantasy novel from the pre-genre period, so I’m looking forward to it!

LikeLike